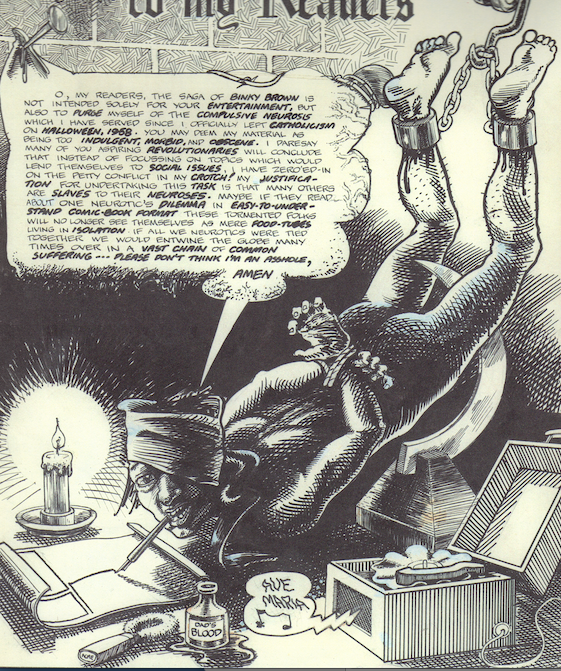

Since roughly 2007, a number of artists in the francophone world who made their careers publishing autobiographical comics in the 90s began to diagnose what they perceived as a crisis in autobiography. Jean-Christophe Menu and Fabrice Neaud are the earliest and most vocal critics of recent autobiographical comics, which, they worry, have become too easily appropriated commercially by giant publishing houses while becoming locked into a codified genre that is depressingly safe and inoffensive. The two authors published an essay entitled “Autopsie de l’autobiographie” (2007). In it, Menu characterizes the crisis as “un appauvrissement, une caricaturisation vers une forme convenue de récit pseudo-intimiste tendant au dénominateur commun” (a thinning out, a caricaturization that leads to a pseudo-intimate, agreed-upon, narrative form that always tends towards the lowest common denominator). In the same essay, Neaud expresses concern that autobiographical comics seem to have lost their transgressive power: “[n]ous obtenons fatalement le résultat qui a fait florès: une forme d’autobiographie light, une autobiographie d’entre potes, cool et sympa, qui […] ne fait de mal à personne et pas davantage de bien.” (we fatally obtain the result, which now flourishes, a diet form of autobiography, friendly, nice, and cool, that […] neither hurts nor helps anyone).

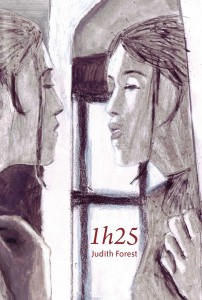

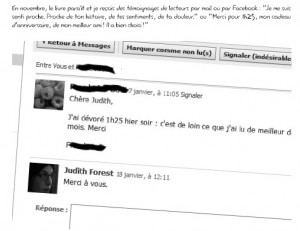

Almost as if to illustrate their point, the Franco-Belgian comics world was shaken by its first highly publicized JT Leroy-style hoax a few years later during the 2011 festival d’Angoulême. Judith Forest, the author of an erotic confessional graphic narrative entitled 1h25, which had received critical acclaim from Arte (an artsy Franco-German television network) and les Inrockuptibles (France’s equivalent to Rolling Stone), was revealed to be a fiction invented by the editorial team at the Belgian press, La Cinquième Couche. What does it mean that Judith Forest, critically acclaimed comics artist, does not exist?

One could make any number of comments here about how an editorially driven autobiography, absent of an actual autobiographical subject, makes literal the crisis in autobiography. But the reality is even weirder than that. As it happens, the authors of the hoax did so not with the intention of driving up sales but rather that of generating discussion about the value of authenticity and the limits of autobiographical comics. They were, like Neaud and Menu, working to diagnose and treat what they perceived to be a problem in the autobiographical vein of comics publishing in the Franco-Belgian sphere. And I don’t think the editorial team expected what one of them described as “a poor graphic equivalent of literary autofiction” to have such huge market success. They meant for it to be poorly written and formulaic, a comment on how perceived sincerity and authenticity can lead readers to overlook formal and narrative weaknesses. But the French-speaking market gobbled it up, along with “Judith Forest’s” second volume, Momon, and the editors at La Cinquième Couche ended up essentially caught in their own trap while also proving their point. Will they feel compelled to continue publishing Judith Forest’s intimate confessions? And if they do, will the lesson about market-driven codified genres lose its power? Who wins? The editors at La Cinquième Couche or the market?

This all may be old news to readers of this blog, many of whom I know also keep track of the Franco-Belgian comics scene, but one discussion I find lacking in regards to the Judith Forest scandal concerns the association of autobiographical authenticity with male fantasized feminine sexual exploration. In the land of impoverished formulaic autobiographical narratives, the story that is imagined to have selling power is that of the sexually adventurous young woman. The all-male editorial team of La Cinquième Couche may or may not have succeeded in playing the market but whatever they accomplished, they did so on the body of a fantasized woman. If they had added a few lines about the gendering of authenticity to their elaborate critical discourse I might be more inclined to appreciate their hoax, but I am not convinced these editors are able to parse the critique of their porn-hungry male audience from that of the fantasized female author. They seem disdainful of both. Both elitist and misogynistic. And in that landscape of many-layered disdain, it seems the editors at La Cinquième Couche never thought to ask the question of whether their project might be exploitative of Judith Forest as a woman, real or not.

What do you think? Can a non-existent author be exploited as a sexual object? Has anything comparable occurred in the Anglo-American comics scene? Do you perceive a similar crisis in anglophone autobiographical comics? For the fun of it, I conclude by reposting Johnny Ryan’s comment on autobiographical comics published here in 2012.