The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

By the time Joss Whedon joined the Marvel wagon, there had already been four distinct movies set in that universe. He would have to continue characters arcs already established in previous movies as well as set up the following installments of the individual franchises going forward. The difficulty of his job lay in having to develop the paths of characters that started before his involvement and maintain a coherent relation with what came before, all the while setting up a end point from which other writers and directors can go off on.

In “‘Avengers: Age of Ultron’ Is the Ultimate Joss Whedon Movie Whether You Like It or Not,” Jacob Hall argues that while Joss Whedon (known for television shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel and Firefly) was “adored by his small, passionate and often overeager fan base, Whedon was a niche talent”, both “too specific and too nerdy” for the mainstream taste. However, tackling the Avengers property ended up being a task Joss Whedon was particularly suited for precisely because he is specific and nerdy. He understood the core elements of the characters and the best way to provide each character with a moment-to-shine and an overall arc. His television work also demonstrated his ability to work with an ensemble cast and he was well known for his comics’ bona fides, having personally written Marvel comics (Astonishing X-Men).

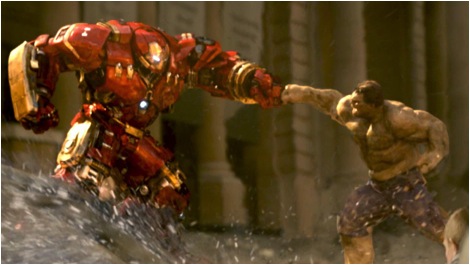

When Whedon comes on board, Iron Man/Tony Stark has, over the course of two movies, been traumatized by his kidnapping in the Middle East and has been using his suit as a form of protection while dealing with the ramifications and repercussions of a war-mongering past. Furthermore, although the suit brings out a heroic side of Tony and while he does make the initial change of not manufacturing more weapons at Stark Industries, his fights have mostly been personal in nature (Obadiah Stane, Justin Hammer, Ivan Vanko). Thor has journeyed from an arrogant soldier to a cast out son to a humbled champion, becoming unarguably worthy of his hammer Mjölnir. Captain America/Steve Rogers is, of all the Marvel heroes, the one with the subtlest arcs because Cap is such a pure hero that he affects the world without letting the world affect him. His sacrifice at the end of Captain America led to a 70-year slumber and meant he lost his place in the world and his girl as well.

Joss Whedon’s greater accomplishment with The Avengers, though, may have been taking the characters who didn’t have their own franchises and fleshing them out. Black Widow had what amounted to a glorified cameo in Iron Man 2, suggesting she was either a mysterious sex kitten or a deadly martial artist. In Thor, Hawkeye had a mere walk-on role and had even less to do than Black Widow. As for the Hulk, both his previous incarnations — Eric Bana in Ang Lee’s Hulk (2005) and Edward Norton in Louis Leterrier’s The Incredible Hulk (2008) — were defined by what Film Crit Hulk defines as “solipsistic detachment”, mistaking the “self-sacrifice” of the character for “relentless dourism”, which meant both iterations were insufferably “mopey”.

In The Avengers, Steve Rogers discovers a way to stay relevant in a world he doesn’t recognize (“Aren’t the star and stripes old-fashioned?”) as the captain of this unconventional team. Thor laments how he “courted war” in his youth, he’s much altered from Thor’s and becomes instrumental due to his relationship to Loki, his willingness to fight for Earth contrastig with the latter’s hubris. Tony Stark learns, via Steve Rogers’ chastisement, to “lay himself on the wire” instead of cutting the wire and going the easy (for him) way.

In The Avengers, Mark Ruffalo and Joss Whedon’s take on Bruce Banner/Hulk is the most successful yet. He is “gentle and dignified”, even if “impossibly weary and haggard”. To my chagrin, I realized the line that most encapsulated Banner’s arc in The Avengers was cut (“Are you a big guy that gets all little, or a little guy that sometimes blows up large?”), but the movie still managed to convey how Banner stops fearing the mindless rampage and uses the Hulk as a tool for purposeful fury — the “other guy” can actually help.

Clint Barton gets the short hand of the stick, and besides being “unmade” by Loki and wanting to put an arrow through his eye socket, Hawkeye has very little to do until Age of Ultron — and even then, it’s less an arc and more an apology from Joss Whedon to Jeremy Renner. Black Widow, however, starts a journey that continues in Captain America: The Winter Soldier and in Age of Ultron. She continues to use her skill set as a spy and precise combatant, but the righteousness of the side on which she is fighting on becomes gradually more important. By the time we reach Age of Ultron, she does the fighting not because she has “red on her ledger” but because fighting in the Avengers, protecting humanity, is the larger-than-life cause she wants to pursue.

The Avengers was a complicated movie, but even so it was a lot simpler than Avengers: Age of Ultron. By the time we reached that movie, not only did Joss Whedon have to respond to his own Avengers, but also to the following franchise installments (Iron Man 3, Thor: The Dark World, Captain America: The Winter Soldier). And beyond that he had to deal with the bigger characters arcs that have been underway since year one at Marvel Studios, along with handling storylines for Twins, Ultron, introducing Vision, allowing time to the dream sequences to matter 1. Amidst all this, it’s not surprising that someone’s story had to be shortchanged; Thor’s character is as sidelined in Ultron as Hawkeye was in the first film. All the Thunder God gets to do is further the Infinity Gems/War overarching (and undercooked) plotline, which suffered from severe and crippling cuts in the edit room that affect the movie as a whole.

In a very Joss Whedon move, in Age of Ultron, the writer/director continues his self-appointed task of paying more attention to the characters that don’t have franchises. Hawkeye gets the secret family that represents what the Avengers are fighting for, and Black Widow 2 and the Hulk get a choice: either run away from their responsibility to save the world (and towards personal happiness) or stay devoted to the cause. The Hulk is changed by Wanda’s interference and reverts to not trusting himself around people, only this time it’s The Other Guy that makes the decision.

Whether at the behest of the studio (although, in interviews, Joss Whedon says it came from him] or not, the inclusion of Wakanda and Klaue, as well as Steve Rogers’ and Iron Man’s conflicting ideologies seem like a set up to future Marvel films (the upcoming Black Panther and Captain America: Civil War), but they’re also symptoms, or rather, the results of two different things. Wakanda and Klaue, just like Vision, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch come from a very nerdy desire to play within the larger playground that is the Marvel Universe. That’s the reason I see for wanting to include Spider-Man and Captain Marvel at the very end 3.

Steve and Tony’s relationship is simply a continuation of both their interactions in The Avengers and their respective arcs within their franchises. Their differences are highlighted by the ways each of them responds to the fever dreams provoked by Wanda, as Tony unwittingly builds another war machine, and Steve accepts that while he will always be mournful of the time he didn’t spend with Peggy, he wouldn’t have done things any differently. They each have conflicting ways of viewing heroism, experiencing trauma and surrendering to sacrifice. Jacob Hall argued that Age of Ultron suffers from being an “overindulgent experience that’s far too mired in continuity and too desperate to set up the next 10 movies in Marvel’s ambitious “Phase 3” schedule”, but it is unmistakenly a Joss Whedon movie, above all else.

Where these are unarguably Joss Whedon movies is in the movies’ themes, witty banter and careful planning of each character. Whedon has won a reputation for telling “tales of personal responsibility” that often revolve around a normal person being appointed an unbearable responsibility given extraordinary circumstances. Both the Avengers movies focus on a team that features both gods and normal people — the normal alongside the exceptional — and argue that what matters are their actions: are they heroes despite their different characteristics, are they bound by a larger calling?

Whedon is also known for his penchant for deaths that matter because he understands the value of human life. The deaths of Phil Coulson (even if reversed) and Quicksilver matter to us as viewers. I’ve seen criticism concerning how Whedon’s decision to have the Avengers save every single person in Age of Ultron, but it certainly underlines the importance of human life. Even if we don’t know the Sokovia victims, they’re still not disposable because they might be someone’s Phil Coulson.

At this point, Marvel movies, or at least the Avengers movies, might function a lot better as part of a continuity than as standalone pieces of entertainment. The movies seem destined to be increasingly steeped in their own mythology.There is a chance, a very palpable one, that Marvel Studios’ movies will no longer be able to be viewed as simply standalone texts. Joss Whedon did a remarkable job, juggling the different plotlines, character arcs and allotting time for each character to have their own moment on screen. I’m curious to see if the Russo brothers, David Ayer or even Zach Snyder, are able to do as nuanced a job as Joss Whedon did.

Ana Cabral Martins (@rrruiva) is Portuguese and is currently finishing her PhD on contemporary Hollywood. She couldn’t think of anything witty to write here.

___________

1. Tony Stark’s PTSD, the grand theme of all Iron Man movies as Devin Faraci has so aptly referenced (See his piece “Earth’s Mightiest Monsters: The Character Arcs Of Avengers: Age of Ultron”), Steve Rogers heartbreak over Peggy.

2. The perceived un-feminism of Black Widow’s infertility is, in my eyes, absurd. She doesn’t say she is a monster because she can’t have children but because she was bred as a killing machine, devoid of choice. Why can’t a well-rounded female character — who is defined by her badass-ness — have feelings or opinions or even reference an inability to have children? Why would that hinder her heroism?

3. At this point, Whedon has been decried from both having played with too many characters and not having been given the free reign to play with many more at the end. His account of the Marvel/Sony deal make it sound like the character had been on the table when it hadn’t and I still don’t think introducing Captain Marvel out of the blue would have been the best way.