H. G. Wells lived in Essex, not Bath, but he did visit here in 1920 while having an affair with feminist icon and fellow eugenicist Margaret Sanger. Both thought birth control would save the world from the breeding of the economically unfit. They also liked the view of the river outside my flat:

“Our visitors began to realize that Bath could be very beautiful.”

Bath is one of Wells’ Secret Places of the Heart, the fictionalized autobiography he published in 1922. He’d been famous since his 90s hits, The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, and The War of the Worlds, which is at least partly why Sanger agreed to meet him while she was visiting England.

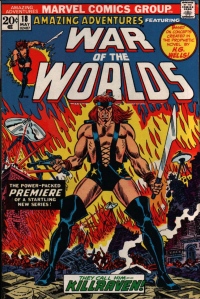

I didn’t meet Wells until 1973 when Marvel published its own War of the Worlds. Set after a second Martian invasion and conquest of earth, its hero Killraven (improbably co-penciled by Neal Adams and Howard Chaykin) sports over-the-knee boots, bare thighs and a navel-plunging neckline.

I showed the cover to my son, who blinked and then mumbled, “Do they give some reason for dressing him like that?”

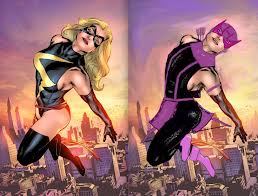

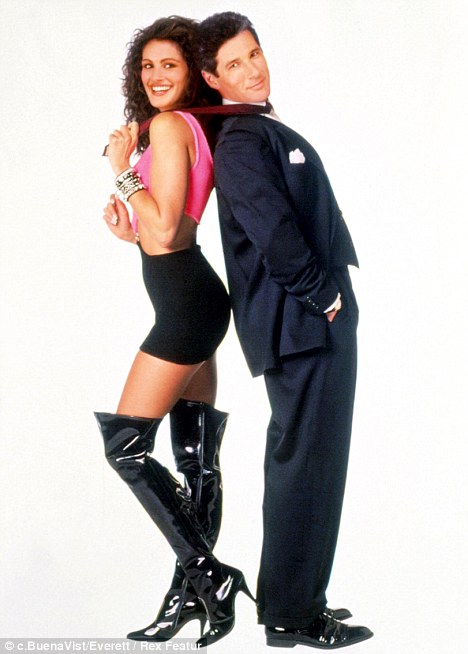

Which is the question that needs to be asked of thigh-booted superheroines too. X-Men artist David Cockrum was soon sketching Killraven’s boots onto Storm and Phoenix. Valkyrie and the Scarlet Witch got the fashion upgrade too. And starting this summer, Wonder Woman’s new costume includes thigh boots.

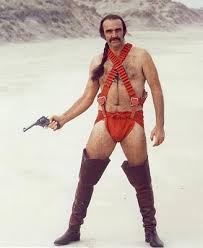

Back in the 70s, Omega the Unknown continued the trend among Marvel males, but the All-Time Best Man in Thigh Boots Award goes to Sean Connery in his gloriously obscure 1974 scifi film Zardoz, in which the post-007 he-man plays a eugenic superman designed to exterminate and/or save Mankind from feminist costume designers from Mars.

Though the look may have originated with Dumas’ ever-so-manly Three Musketeers, thigh boots have spent more time strolling the women’s side of the fashion aisle—usually under red lights, as indelibly displayed by Julia Roberts’ 1990 Pretty Woman.

The same was true in 1890, when the thigh boot was first making its way up the legs of London prostitutes. H. G. Wells visited his first at the tender age of 22, when his “secret shame at my own virginity became insupportable.” He termed the woman “unimaginative,” so she probably wasn’t up on the newest in fetish footwear.

The experience, Wells reports in his surprisingly sexual memoir, only “deepened my wary apprehension that round about the hidden garden of desire was a jungle of very squalid and stupid lairs.” Which might explain his Martians. Although they “wore no clothes,” they’re nothing like the genetically engineered super-seductive Sirens Killraven faces in the final panel of Amazing Advenures No. 18. H.G.’s Martians “were absolutely without sex, and therefore without any of the tumultuous emotions that arise from that difference among men.”

His Martians bud from their parents like fresh-water polyps. And yet they probably “descended from beings not unlike ourselves.”Imagine the human race devolving into a single sex. Writers for Syfy’s Warehouse 13 (my wife and I watched a season or two with our then pre-adolescent son) cast actress Jaime Murray as a thoroughly female H. G. Wells, a gender-bending experiment that thus far has not plunged our world into asexuality.

Helena (“Herbeta” must have sounded too lame) almost got her own spin-off series, but Stephen Spielberg has shown no interest in sequeling his 2005 War of the Worlds remake. Some scenes were shot just outside my town. Tom Cruise even stopped by our ice cream shop and left a personal check in the change jar for a needy local. Tom is 5’7”, the cut-off height for extras advertised in our weekly paper and one of many reasons I did not apply.

Wells couldn’t have applied either. The average Victorian male towered under 5’6”, though Wells was short even in that stunted context. He’s also been called tubby and squeaky, and yet he was a male siren to the string of mistresses he wooed after shedding his virginal shame. He titled one of his autobiographies H. G. Wells in Love, which remained unpublishable until well after his conquests’ deaths. He must have had a thing for feminist icons, because Rebecca West makes the list of not-so-secret lovers too. One of my sister’s coffee mugs quotes her: “I only know that people call me a feminist whenever I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat or a prostitute.”Actually, the mug makers deleted the last three words, even though they do reflect Wells’ continuing interests. He was still visiting the jungle lairs of American call girls at the tender age of 74.

I don’t really want to know how “imaginative” they were, but Killraven grew more so after artist P. Craig Russell inherited the series. He kept the thigh boots, but slipped on a pair of trousers and an asymmetrical battleblouse. The style was chaos to my eight-year-old eyes, but looking back now I see why Russell has been likened to art nouveau, the fashion rage when H. G. Wells first serialized War of the Worlds in 1897. Superheroes were supposed to throw hard-edged punches, but Russell’s lines are soft, his vision literally flowery. Killraven’s battle with the butterfly-woman may not reach Maxfield Parrish heights, but even as a kid I sensed something perplexingly androgynous in those curves.

Wells’ sexless Martians avoid such tumult. They’re just brains with tentacles—though, like Bram Stoker’s Dracula published the same year, they have a lust for human blood. Russell serves them infants on platters, and Killraven was bred to feed their appetite for gladiator sport. Scenes from Dracula have been anthologized in Victorian erotica collections, but Tom Cruise’s bouts with the Martian blood-suckers included no sex scenes. It’s just as well costume designer Joanna Johnston didn’t lace him into thigh boots.

But Tom did accidentally gender flip himself when Angelina Jolie took his role in the 2010 spy thriller Salt. Jodi Foster only reads for male parts, which, sadly, is how she ended up in Elysium. Sigourney Weaver turned Alien into a four-film franchise the same way. And even Sean Connery has to admit Judi Dench is the best M in Bond history.

Strong Female Characters have been taking the initiative for a while now. A 2007 study in Mass Communication & Society investigated “whether or not animated superheroes were portrayed in gender-role stereotypical ways.” To the researcher’s surprise, they found “that females are being presented as more masculine” by adding “the masculine trait of aggression to a character who is already portrayed as having traditional feminine traits such as being beautiful, emotional, slim, and attractive” while deleting “domesticity” and “passivity.”

Although the authors acknowledge their findings could suggest “female superheroes are finally breaking down the gender-based stereotypes,” they’re also why the Hawkeye Initiative wants to “fix every Strong Female Character pose in superhero comics” by replacing “the character with Hawkeye doing the same thing.”

It’s a great project, but even the best of the parodies can’t touch the accidental parody of the original thigh-booted Killraven.

The long-running trend to hyper-sexualize superheroine bodies is a reaction to female characters taking on that so-called masculine trait of aggression. Comics creators are afraid we’re devolving into unisexed Martians. Like Wells, they are big believers in “that difference.” Since domesticity is extinct, artists like Todd McFarlane counter-balance female aggression by inflating female sexuality. They’ve bred superheroines into battle-prostitutes.

I think humans have more in common with Martians than we care to think, but I’m glad no fashion aliens are trying to fit me into thigh boots just yet. Killraven started wearing his in the no-longer-distant year of 2017. That’s a future I hope humankind avoids. But it beats Wells’ alternative: