So: Thursday 7 June 2012, a day which will live in infamy.

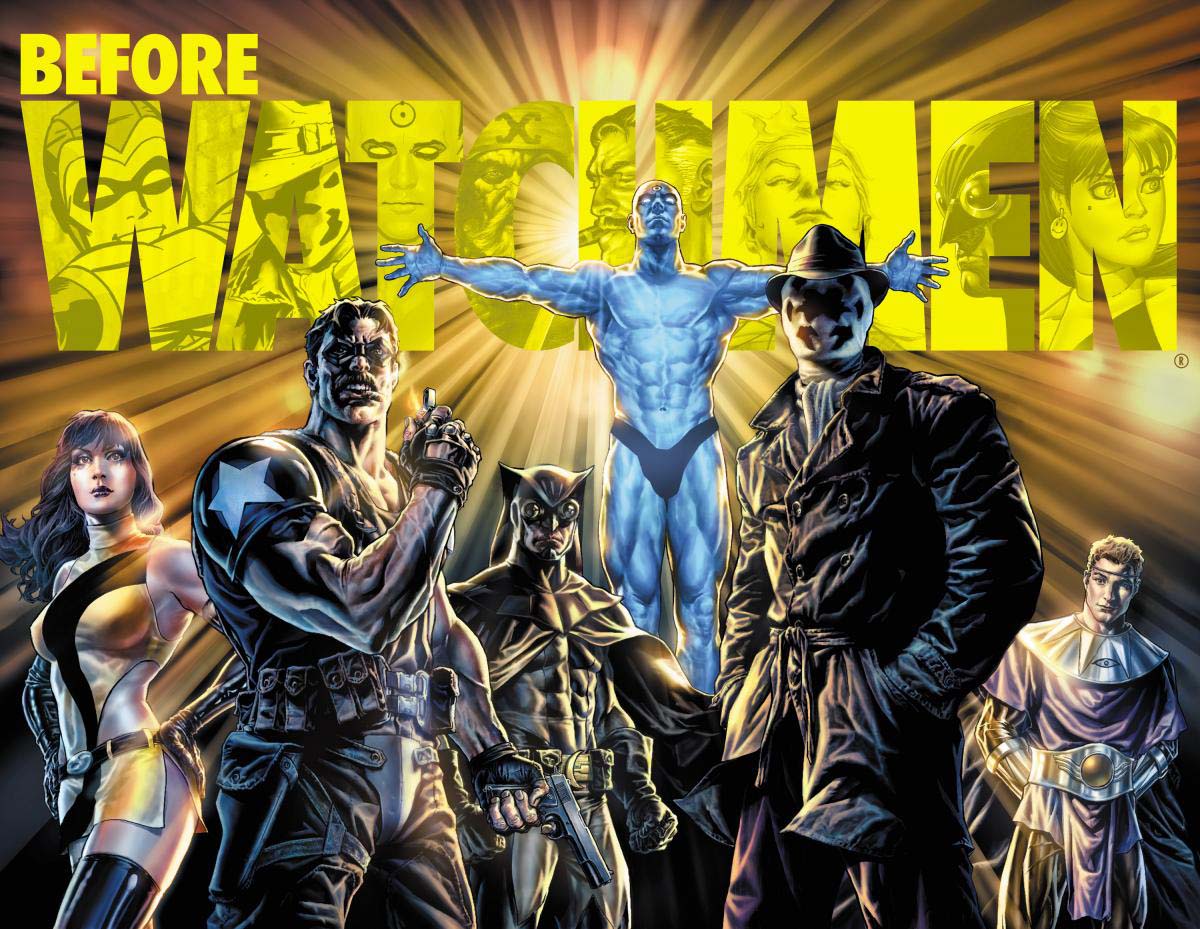

I’m not going to go into why Before Watchmen is an all-round immoral “product”, why the *cough* artists involved are sell-outs and scabs, and why those who buy it are endorsing and enabling exploitation. Others have made that case better than I could — I particularly agree with most of what Noah says here.

And, yes, I do agree with that, in spite of my — admittedly rather dopey, it even says as much in the title — earlier post here, where I detailed in tedious detailly detail just how extensively Alan Moore’s own career has relied on the exploitation of other people’s characters, often in ways that the original creators would find abhorrent. My point there wasn’t exactly a tu quoque — i.e. that if it’s okay for Moore to do it, then it’s okay for Dan Didio and his homies to do it too. My point was that — money aside, and that’s a big thing to put aside — Moore has harmed the interests of (e.g.) Lewis Carroll just as much as Didio et al. are harming the interests of Moore. It doesn’t hurt Lewis Carroll — again, money aside — any less just because he’s dead.

This is because I hold the philosophical view (prima facie very counter-intuitive) that the dead have interests just as much as the living, and that we can harm them or benefit them in similar ways that we can harm or benefit the living. Weird, right? But that doesn’t mean that it’s wrong for Moore to fuck over Carroll, or that it’s okay for Didio to fuck over Moore, because ceteris ain’t paribus here. There’s a benefit to society from letting creators mess with the creations of others, but there’s also a benefit from postponing such messing in favour of some length of copyright. So even though Moore has done Carroll wrong, what he’s done is nevertheless morally okay because that harm is outweighed by a greater good. And contrariwise for what DC is doing now.

Which more or less chimes with what Noah’s said.

But to the extent that my post may have contributed to anyone’s impression, in even the slightest way (I have no illusions about the extent of my online persuasive powers), that Before Watchmen is morally acceptable, then mea honest and sincere culpa.

Now, all that said, I want to move on to a much more discomfiting thought. At least, it discomfited me. And this is directed at all of us who have taken the moral high ground on this “package” and exciting new “development” of the “property”, so other people like Noah, Tom Spurgeon, Dan Nadel, Sean T. Collins, Abhay Khosla, Chris Mautner, J. Caleb Mozzocco, Tucker Stone, et al.. You know who we are.

Um, we know who you are?

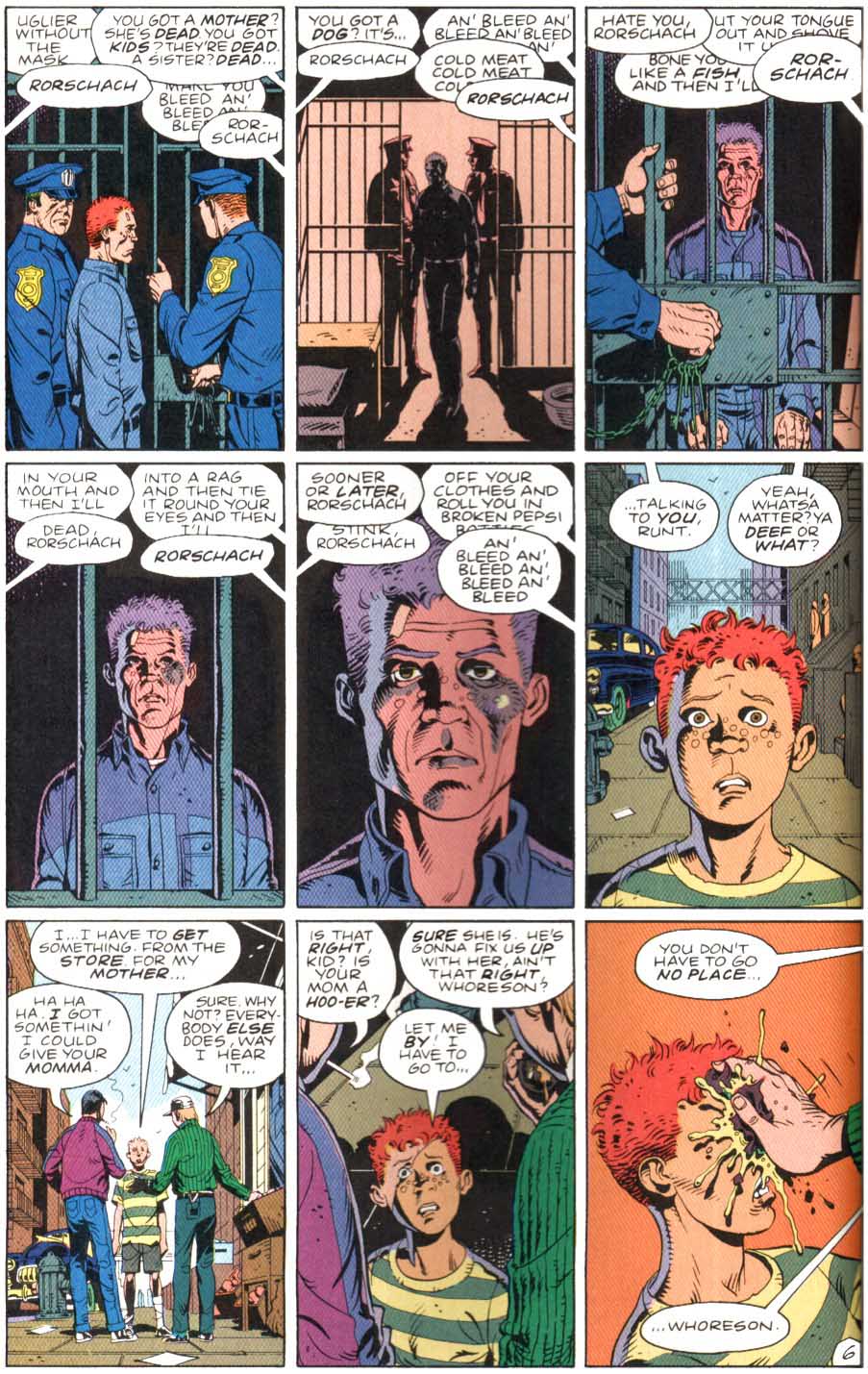

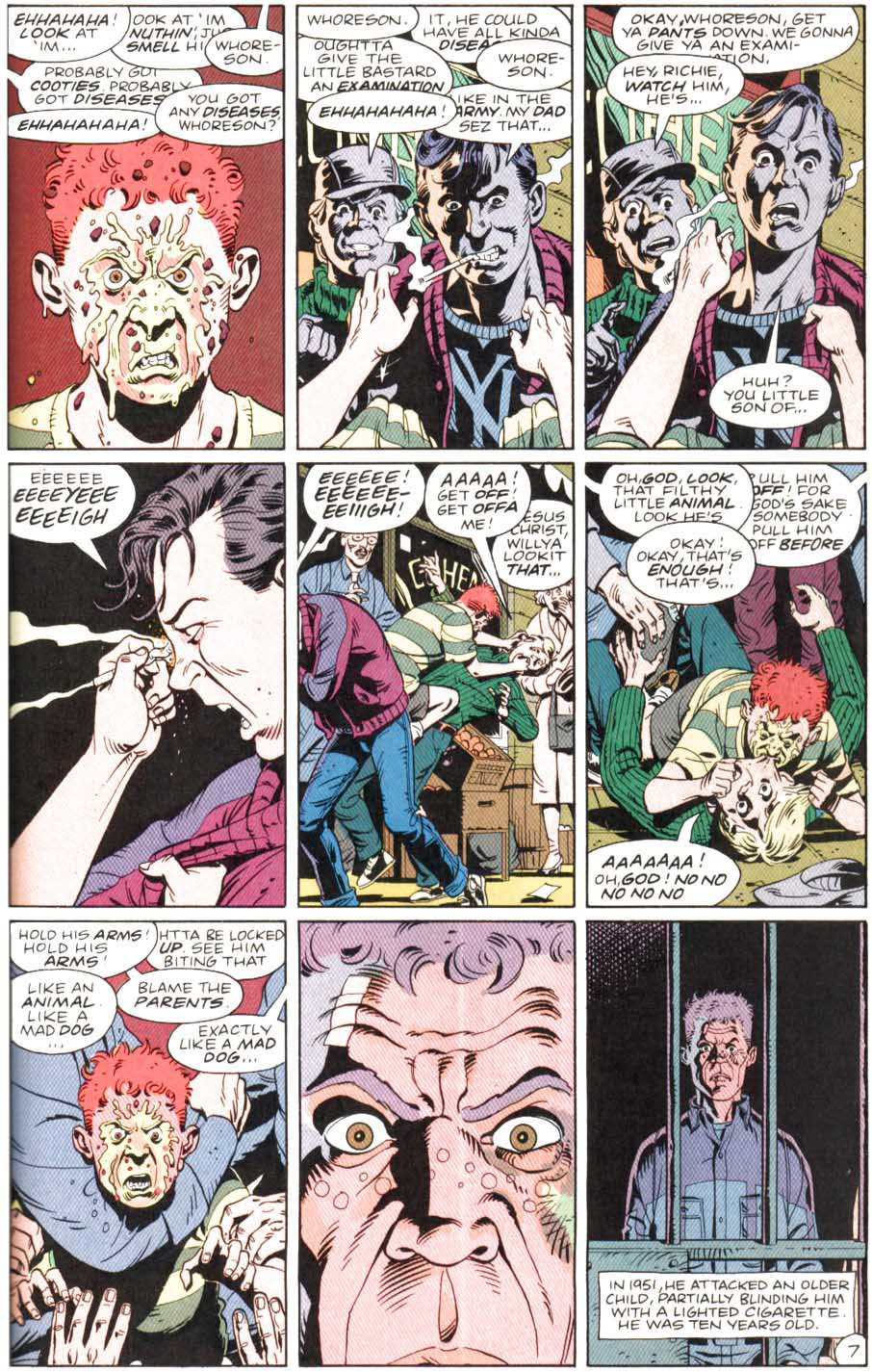

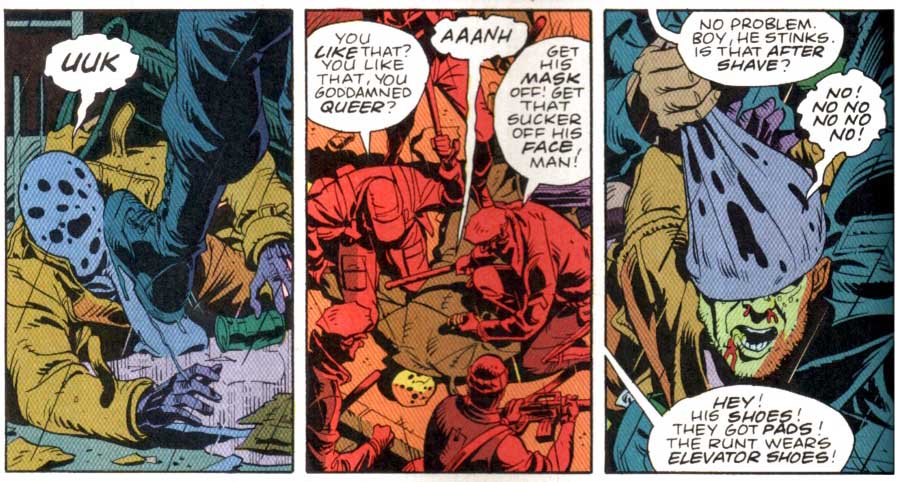

Eh, whatever. Anyway, here’s the thought: how much of our moral disdain is due to the fact that we have 99.9% certainty that Before Watchmen is going, as Socrates might have put it, to suck dead dogs’ balls?

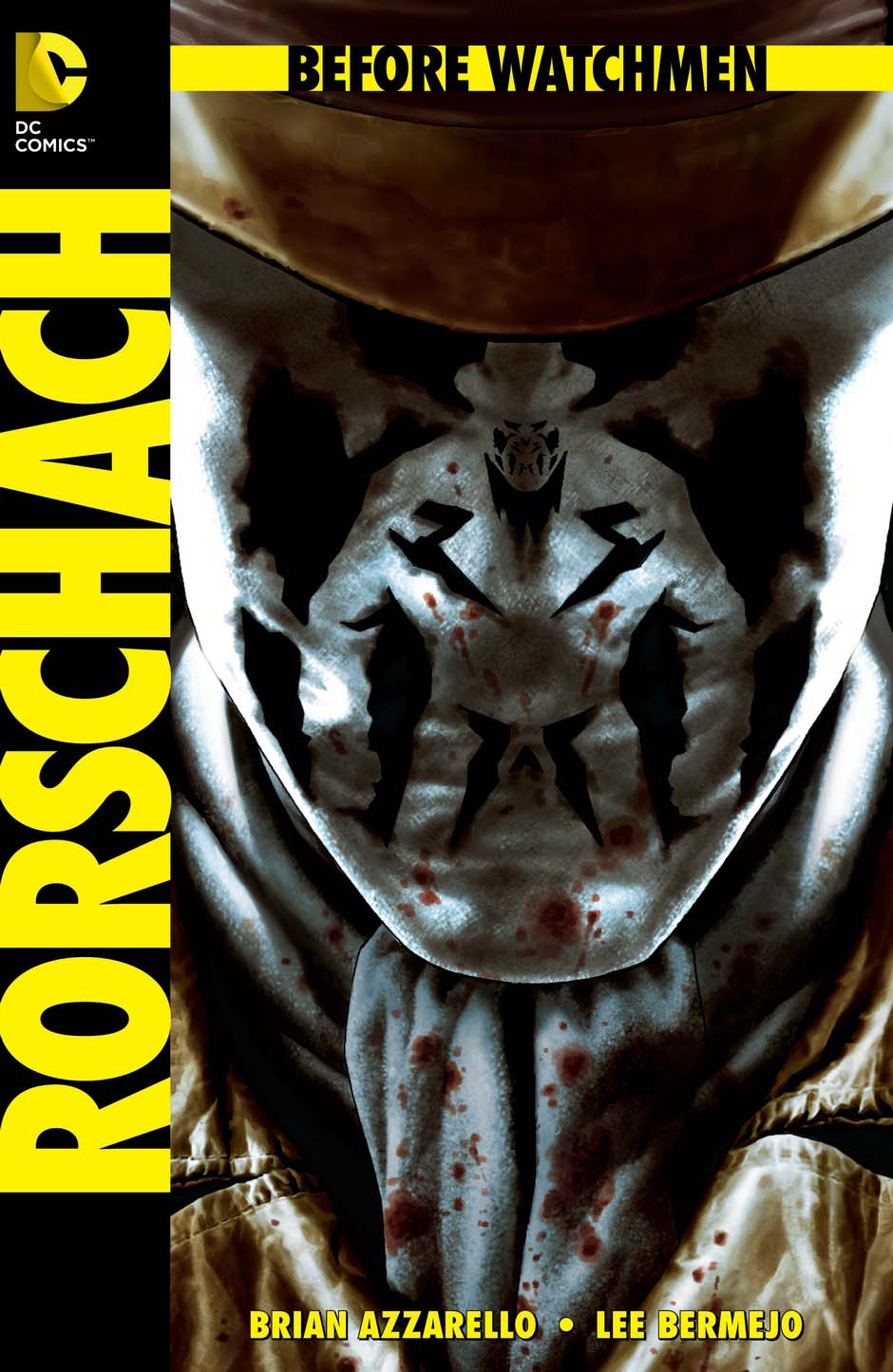

Let’s look into our hearts here: hasn’t DC made it incredibly easy forus conscientious objectors to conscientiously object because, come on. J. Michael Straczynski and Darwyn Cooke? Shit, DC, why don’t you make it really tempting for us and chuck in Brian Michael Bendis and Jim fucking Lee? Of all the *cough* artists involved, Brian Azzarello and Jae Lee are the only ones I’d personally piss on if they were on fire; many of the rest of them I’d only piss on if they weren’t on fire.

Not Dan Didio, though. He seems like the kind of guy who’d be into that.

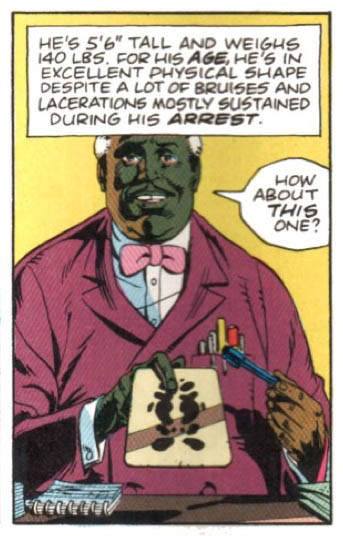

Let’s imagine an alternate universe where the “talent” involved was actually talented. Let’s imagine that, instead of Andy Kubert and JMS, the line-up consisted of Chris Ware, Jim Woodring, Lewis Trondheim and Junko Mizuno. Or Anders Nilsen, James Stokoe, Los Bros, Jason, and Naoki Urasawa. Or a young-alt-star-all-star line-up, drawing six hundred pages of nothing but hardcore yaoi fucking, Dr Manhattan as top and Rorschach as bottom: Johnny Negron! Lisa Hanawalt! Michael de Forge!

Or whoever floats your boat. The particular names don’t matter, what matters is that we imagine a line-up of artists who are actually, you know, good and who would almost certainly produce something that’s actually, you know, good.

In the real world, with the line-up we’ve in reality got, there’s essentially zero chance that Before Watchmen will be as good as Watchmen. Hell, there’s essentially zero chance that Before Watchmen will be as good as The First American.

But imagine — just imagine — that it was probably going to be good. Maybe even great. How loud would our denunciations be then? How many of us would still boycott?

Yeah, lots of us would would still denunciate, lots of us would still cott the boys. But, let’s be painfully honest, lots of us would be slinking off to the LCS to buy it, put it in a brown paper bag please or if you don’t have a brown paper bag could you please hide it in the covers of Pee Soup um I’m buying that for my friend

Uh his name’s Dan.

In other words: while we’re all basking in the warmth of our moral outrage — and I’m there basking too, man, that one place in the sand where there’s just one set of footsteps and it looks like I just nicked off to do my own thing? that’s where I stopped to carry you I LOVE YOU GAIZ!!! — while we’re all there basking, let’s also take a reality check. The reason it’s so easy for us to think DC management are arseholes for publishing Before Watchmen, the reason it’s so easy to think the *cough* artists are arseholes for making it, and the reason it’s so easy to think the readers are arseholes for buying it — that’s not because we are not, ourselves, also arseholes.

We’re just arseholes who, this time, got lucky.

Boringly sensible post-script: Yeah, yeah, some of us would still resist, just as there are some people who find meat delicious but still turn and remain vegetarian. And there are also some people who genuinely do like the artists involved in the real Before Watchmen and are still loudly denouncing it, with David Brothers leading the charge. Good for them.

Second post-script: Come to think of it, an alt-comix tijuana bible/doujinshi sounds like a good idea. Internet, make this happen! Paging Ryan Sands…

Image attribution: Ah, Google. Seek “Watchmen yaoi” and it shall be given. Art by Pond; I hope s/he doesn’t mind the borrowing. I just wanted to build on his/her legacies and enhance them and make them even stronger in their own right.