[The first part of this article (Les Cités Obscures: The Great Walls of Samaris) can be found here. Fever in Urbicand was first translated into English in the pages of Cheval Noir and later reprinted in album format by NBM in 1990.]

“In my youth, fooled by the illusory theories of the Xhystos and Tharo architects, I momentarily succumbed to the turbid charms of the arabesque. However, I soon regained my sense and discovered the profound nature of our art. I realized that in every circumstance, simplicity is preferable to affectation, steadfast attention to a single effect is better than a thousand strokes of inspiration, and at every moment the conception of the whole must prevail over obsession with detail.”

Eugen Robick, Fever in Urbicand

Benoît Peeters and François Schuiten’s second album in the Cités series seems, in part, a reverberation from the events in The Great Walls of Samaris. It may in fact suggest a path humanity should be taking.

Within the pages of Fever in Urbicand, an apathetic citizen by the name of Eugen Robick (whom Franz finds occupying his girlfriend’s apartment at the end of The Great Walls of Samaris) becomes an instrument of reconciliation and hope.

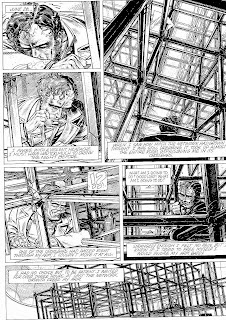

Robick is Urbicand’s chief urbatect and thus a synthesis of the artistic and scientific genius. The story begins when he is presented with a virtually indestructible and seemingly useless metal lattice cube, an object which he immediately loses interest in. The cube is first discovered at the Von Hardenberg construction site, a veiled reference to the author and philosopher, Novalis.

There are a number of interesting links between Novalis and Les Cités Obscures. Novalis’ oeuvre includes idealistic philosophical allegories like Pollen and Faith and Life. In Novalis’ Heinrich von Ofterdingen, the hero searches for a symbolic blue flower which is the color of the Drosera in The Great Walls of Samaris. In yet another tribute to Novalis, Peeters has named Robick’s girlfriend, Sophie, in memory of Novalis’ own fiancée, Sophie von Kuhn.

It seems safe, therefore, to assume that Robick’s apathy is intended as a metaphor for intellectual disdain for small yet potentially significant forces – an attitude which is shared by the government and academicians of Urbicand.

Robick is preoccupied with the important task of building bridges joining the Northern and Southern banks of the city. Passports are required for crossing these bridges and it is quite apparent that the river dividing the city is a symbolic frontier line separating essentially similar peoples. Like the intellectuals of Castalia in Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game, however, Robick shuns anything overtly political. Absorbed with artistic endeavor, he fails to understand what soon becomes so fascinating to the citizens of his city. His initial concerns are merely directed at the symmetry, stability and aesthetic perfection of his creations. Like Plinio in Hesse’s novel, he has become “unpleasantly strange to others” and incapable of understanding them. The authors, thus, do not merely decry elitism but also the failure of intellectual and artistic communities to provide leadership and direction for society.

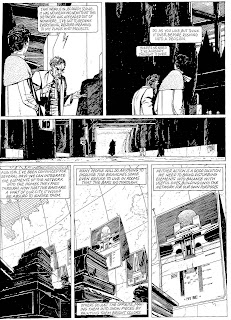

The reader is treated to the sights of Urbicand through Robick’s long walks and explorations. The city exhibits a reserved expression of Art Deco (and Art Nouveau) ideas, a typical example of which would be the “sober, geometric” Stoclet Palace in Schuiten’s native Brussels, with its carefully trimmed trees and prominent tower. All these and more recur with some regularity along the streets of Urbicand. There are statues which recall the work of Joseph Maria Olbrich and interiors which touch on the simplicity and reserve of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The rectilinear and symmetrical forms so loved by Art Deco artists are prominently displayed in a proliferation of female and animal sculptures, furniture and wall paper designs. At one point in the album, Schuiten depicts an immense avenue flanked by a stern, bare building with the word “mortalis” inscribes on its façade. This huge mausoleum is further romanticized and made symbolic by cypress trees planted at the termination of the avenue.

Schuiten redefines his spatial expression for this story. In one instance, a long narrow corridor with high walls creates a variation on Gothic space with a magnificent office at its termination substituting for an altar.

As Peter Collins describes:

“…in the nave of a Gothic cathedral the high walls closely confining the observer on two side restrict his possible movements, suggesting advance along the free space of the nave towards the altar; or their compression forces him to look upward to the vaults and the light far ahead, there to feel a sense of physical release, though he is earthbound.”

In another instance, pedestrians on open walkways are engulfed and dwarfed by the massive buildings which surround them. The emphasis on stone masonry, towering doorways and massive staircases lend an air of monumentality and majesty to Urbicand which begins to resemble a sort of temple glorifying the State.

Within a day of its discovery, the cube begins to grow at an amazing pace, forming a network as it does so. Quiet, unbreakable and indifferent to external matter, the network passes through Urbicand like a giant metaphor for Mikhail Bakunin’s anarchistic pan-destructionist theories save for their excessively violent elements. The network is thus an indefinable, immortal force replacing the terrorism that has littered history; leading all classes in a “spontaneous revolution” against the government.

Amidst the turmoil, the visionary qualities in Robick creep into play as he readily accepts the need for savage elements to highlight the “unity of the whole”. He lectures a skeptical academy on the workings of the network and, later, maps the extent of the network to best benefit from its presence. Gravitating towards the other extreme is his friend, Thomas, the consummate bureaucrat. He is the only person to recognize the magical properties of the cube from the outset and remains firmly against the network and its adherents for the better part of the book. The third major character, Sophie, is a free spirited and open minded procuress. She remains a tribute to Sophie von Kuhn in name only. As fickle in her commitments as she is in love, she sets herself up firstly as Robick’s public relations officer but later defects to Thomas’ cause.

To the populace, the network is both captivating and terrifying. Robick who is merely the victim of tumultuous events, is hailed as the ideological leader of the movement and as a result cast into prison. Military intervention and government propaganda is stepped up even as the North and South banks of the city become freely accessible to the people. A ponderous attempt to destroy the network using an antiquated cannon (a somewhat telling symbol) results in disastrous losses for the aggressors. What follows is a sudden and final breakdown of the judicial system as the geometric growth of the network makes all forms of incarceration untenable.

The sudden stabilization of the network results in unprecedented freedom for the citizens of Urbicand as the various classes of society are finally physically (if not spiritually) united. When Robick, awash with misconceptions, is pressed into visiting the North Bank by Sophie, he discovers what we have suspected all along.

The North Bank can best be described as a tenement area with dilapidated buildings and poorly clothed inhabitants ennobled by their friendliness, tolerance and eagerness to learn of the South Bankers. The affluent, sophisticated South Bank residents are portrayed in a similarly idealistic vein, coming across as understanding, sociable and unprejudiced.

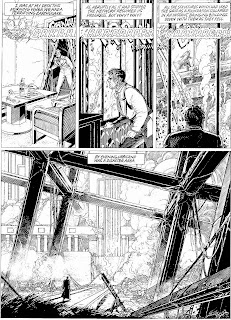

Indeed, the efficiency of the network in dismantling the trappings of government is matched only by the miraculous spirit of cooperation and innovation exhibited by the population: exchanging houses becomes common between people staying on opposite sides of the network; municipal government officials begin to take indefinite leaves of absence abandoning the civil service; walkways and railing are quickly set up along the metal beams of the networks; toll booths are set up to demarcate and signify property lines; crops are grown using the network as scaffoldings; and when ice makes the network inaccessible to pedestrians, tram cars and elevators are set up to ease travel during these periods.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon probably envisioned a society along similar lines when he developed his own form of anarchism, Mutualism. In Proudhonian Mutualism, policies are shaped purely by the will of the people and the possession of land an essential ingredient in the liberation of the working class. Business is undertaken for mutual interest and unbound by laws; disputes are settled by arbitration. At this point, it seems appropriate to note that Robick does bear some resemblance to the bearded Proudhon.

Proudhon is hailed as the first man to declare himself an anarchist. He was harassed by the authorities and even underwent imprisonment. He was involved in the Revolution of 1848 “which he regarded as devoid of any sound theoretical basis”. He was “a solitary thinker who refused to admit that he had created a system and abhorred the idea of founding a party” (George Woodcock).

Sophie illustrates another aspect of anarchy – the expression of bodily freedom as demonstrated through publicly sanctioned encounter houses (essentially pavilions for the purposes of sexual orgies) at the intersections of the network.

Robick, who views the “pleasant state of chaos” as inefficient and unconstructive, begins devising new buildings to “bring disturbing elements into balance with useful ones”. Among his designs is one which draws upon the image of Olbrich’s Sezession House in Vienna right down to the “golden cabbage” dome.

This “parody of classicism and imitative historicism” is a symbolic call to break with the past. It is not an insignificant or fanciful choice for the original building heralded a new era of experimentation and change. While Art Nouveau today may be closely linked with decorative designs of Xhystosian architecture, it allowed for a diversity of modern styles and ideas. The Sezession House is the symbol of a new art belonging to a new unfettered attitude towards life. Its lack of luxury conforms to the anarchistic ideal.

On a trip to the outskirts of the city, Robick discovers that the network has attained the shape of a pyramid slightly tilted on its side due to Thomas’ angular displacement of the cube on Robick’s table at the beginning of the story. This reiterates the idea that bureaucratic involvement of any kind is singularly detrimental to anarchistic revolution. The fact that the cube only starts to grow on Robick’s table suggests that it is the place of the intellectual to nurture such movements. It is fitting that the most enduring and perfect structures ever created by man should come to represent the spirit of freedom. It is perhaps subtle irony that what once represented the Egyptian “autocratic ideal” of central government and the powers of the pharaoh is here used to express solidarity and individual action.

Peeters’ and Schuiten’s idealism is tempered with a tinge of realism for even pleasant dreams must come to an end (and all too often with a shock). The new order is shattered when the network resumes its growth, destroying everything built upon it. The powers that be swiftly reassert themselves and Thomas, who has unwaveringly opposed the network, is chosen by the people to re-establish order in the face of chaos. Memories are, however, slow to fade. Some citizens cling tenaciously to the miracle of the network. Climbers attempt to scale the fast disappearing structure while others fervently hope and pray like zealots for its return.

In the closing pages of the book, Thomas, hoping to counteract the despondency of his people, seeks Robick’s help to build an artificial network. Robick refuses but supplies his maps to Thomas to aid the undertaking. When work finally begins, Robick can only describe the resulting structure as a “grotesque caricature”.

Robick has an alternative solution, one which constitutes the message of this tale: the recreation of the cube. The album closes with Robick beginning the difficult process of invention by making a crude stone replica of the original lattice cube. In the absence of radical social reformation, a slower, more taxing process of trial and error is adopted. It is quite possible that the utopia created by the network may never be attained through this laborious process of evolution. On other hand, as Herbert Read states in the The Cult of Sincerity:

“My understanding of the history of culture has convinced me that the ideal society is a point on a receding horizon. We move steadily towards it but can never reach it. Nevertheless we must engage with passion in the immediate strife…”

The anarchistic ideal thus becomes a standard by which to judge our society, an ever present reminder to guard against over-organization and regimentation.

A full color newspaper insert in an issue of À Suivre published some years after the release of Fever in Urbicand shows Robick hard at work in his factory and with some measure of success in his endeavors. A touch of optimism on the part of the authors perhaps…(cont’d)