We’ve had several posts on race this week, so I figured I’d finish up by reprinting this piece from Comixology. I think it’s one of Jeet Heer’s least favorite things I’ve written, if that’s any incentive.

__________________________

As cartoonists go, Robert Crumb is quite, quite famous. Still, there’s cartoonist famous and then there’s rock star famous. Which is to say that for all his notoriety and the cultural currency of “Keep on Truckin'”, the Crumb image that has been seen by most people is probably still his iconic 1968 Cheap Thrills album cover for Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin.

It’s somewhat unfortunate that this is one of Crumb’s defining images. Not that it’s bad. On the contrary, the inventive layout, with images radiating out from a central circle is pleasingly energetic, and the drawing, as always with Crumb, is great. Plus, cute turtle! The only thing is….

Well, it’s kind of racist.

Crumb’s oeuvre not infrequently delves into reprehensible blackface iconography. Sometimes, (as in his Angel McSpade strips) he seems to be trying, at least to some extent, to critique or mock the imagery. In the upper right of the Cheap Thrills drawing, though, he seems to use blackface simply because (a) that’s how Crumb draws black people when he’s drawing cartoons, and (b) racist iconography = funny!

The racist image in question is an illustration of Joplin’s cover version of the famous Gershwin tune from “Porgy and Bess.” The song itself, written by a Jew to capture the sound of African-American spirituals using elements from Ukrainian folk tunes, is one of America’s great cultural mish-mashes. Though its lyrics evoke the happy darky stereotype (“Summertime, and the living is easy…”) its mournful, heartfelt tune suggests a barely suppressed sadness — a weight of hardship hidden for the sake of love beneath a lullaby. My favorite take on the song is probably Sarah Vaughn’s effortlessly heartbreaking rendition. In comparison, Joplin’s hoarse bombastic reading sounds strained and clueless. The rendition is bad enough that it even becomes borderline offensive: almost the very minstrelization of black experience that Gershwin, through a kind of miracle, managed to avoid.

In that sense, Crumb’s image for the song could almost be seen as parody; a vicious sneer at Joplin’s blackface pretensions, caricaturing her as both a wannabe black mammy and as the whining white entitled brat looking to the exploited other for entirely undeserved comfort. As I said, it could almost be seen as that — if Crumb hadn’t thrown in another entirely gratuitous blackface caricature in the bottom center panel, just to show that, you know, he really is exactly that much of a shithead.

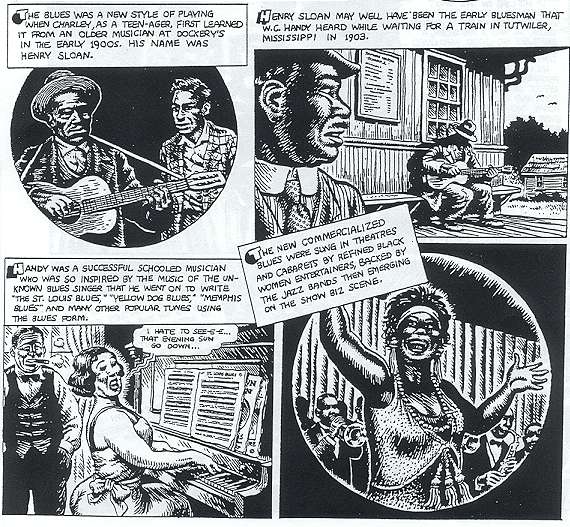

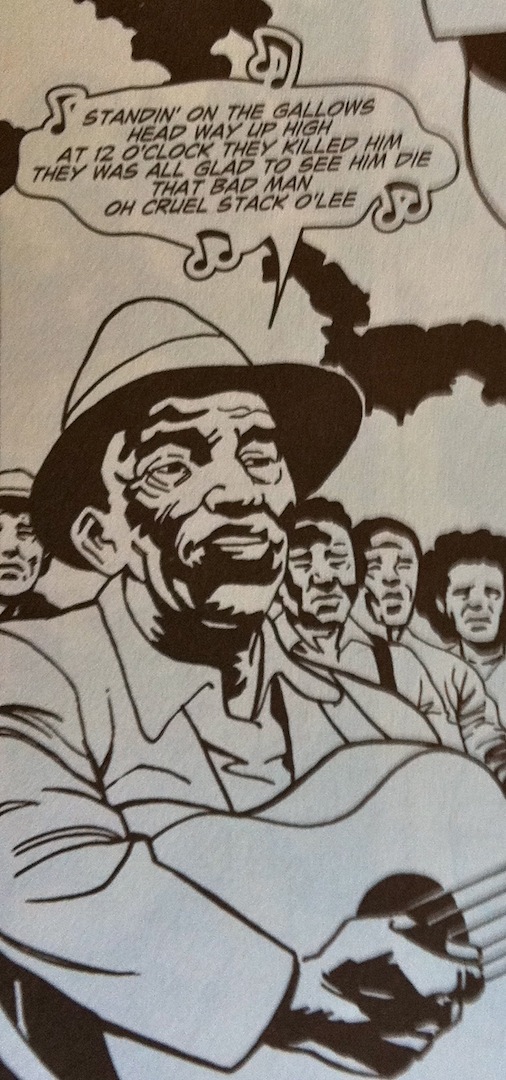

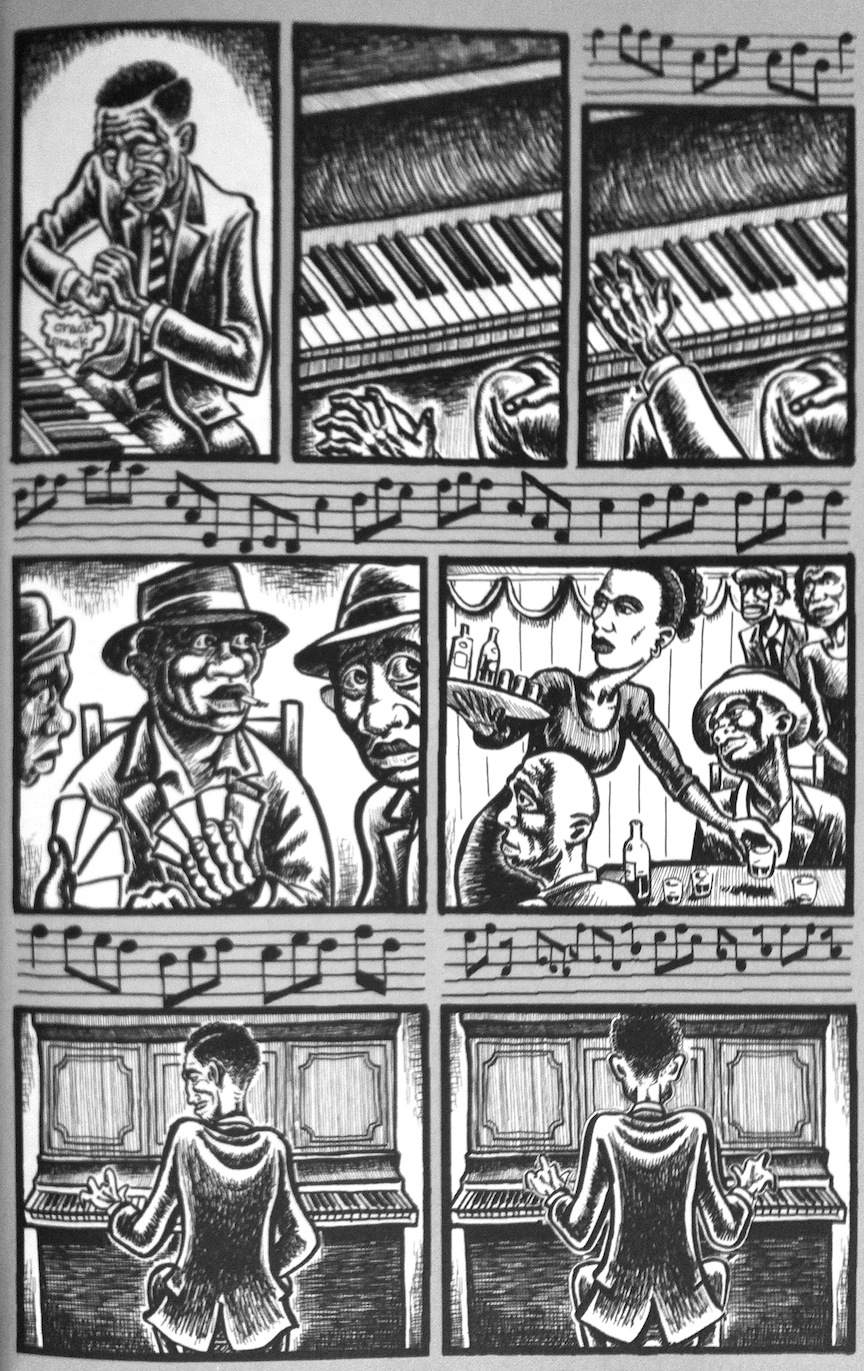

Given the grossness of the Cheap Thrills cover, it’s interesting that Crumb has, in the intervening years, gained a reputation as a particularly thoughtful interpreter of the black musical experience. His passion for 1920s-30s blues and jazz records is well known, and he’s done some cover art for blues releases. He’s also written comics focusing on blues history, perhaps the most lauded of which is “Patton” from 1984, a 12-page illustrated biography of legendary delta bluesman Charlie Patton.

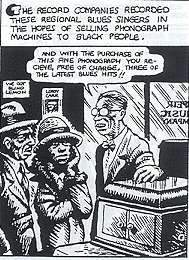

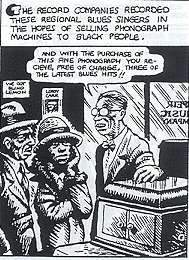

“Patton” absolutely eschews blackface caricature. Indeed, it more or less eschews cartooning, opting instead for a more realist style which seems to draw from photo-reference for its portraits of Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, and others. Walk-on characters, though, are also portrayed as individuals. A black man and woman contemplating buying a phonograph, for example, are humorous not because they’re exaggerated, but because they aren’t; their faces are fixed in ambivalent desire and nervousness as they try to determine whether this, right here, is going to break the bank.

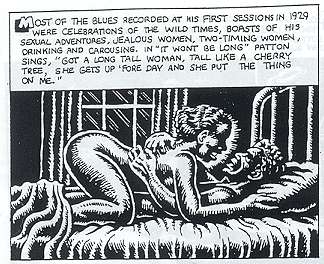

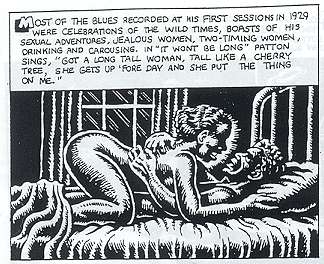

At the same time — it wouldn’t be quite right to say that Crumb dispenses with caricature. He just uses it more subtly. Some of his drawings of women in the strip are impossibly mobile, curving rubberlike to accentuate the more interesting bits:

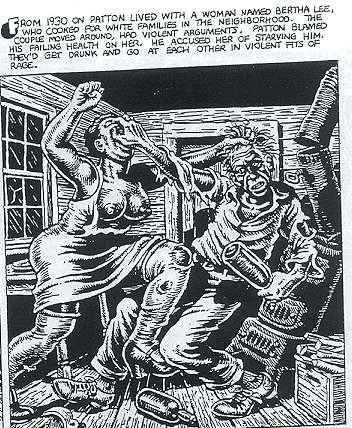

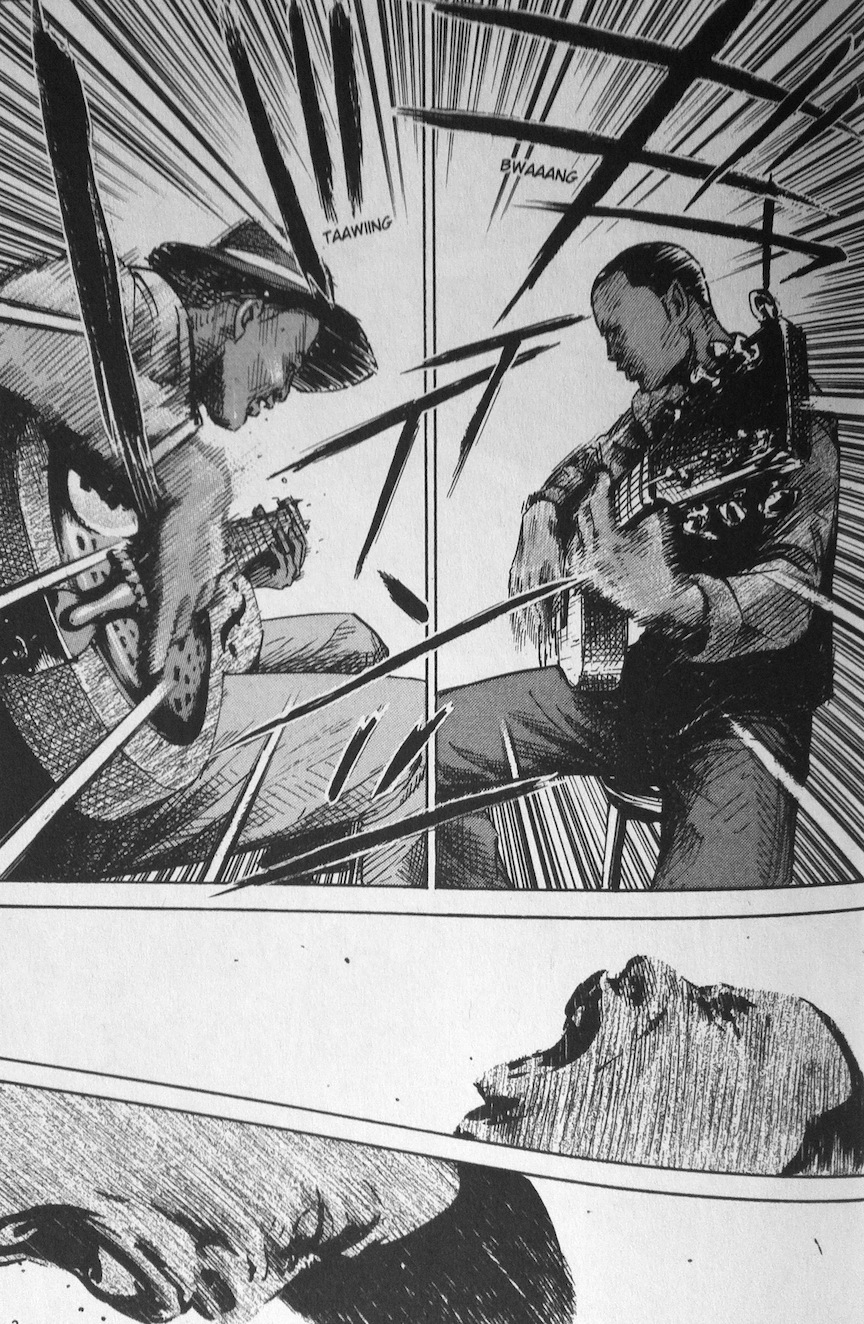

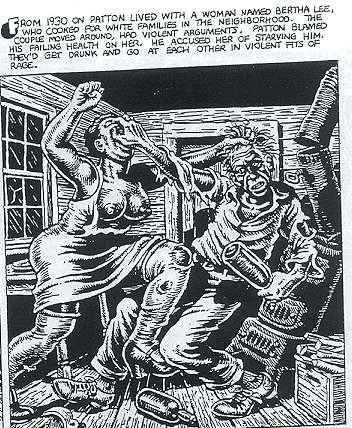

Crumb’s fascination with the female form is no particular surprise given his oeuvre. Here, though, it’s subsumed within a grander project of fetishization aimed at Patton himself. Crumb’s recounting of the bluesman’s life is matter-of-fact, but there’s little doubt that not just Patton’s musical genius but his shiftless, earthy, sex-and-violence drenched life is a huge source of attraction for the cartoonist. You can see it in the enthusiasm with which Crumb’s pen limns the posterior in that picture above, as well as in the gratuitously R-rated fight scene below:

But I think Crumb’s fascination also comes out in subtler moments. There’s this passage for instance:

“The tin-pan alley blues barely touched the remote rural black people of the Delta region, where the real down-to-earth blues continued to evolve as an intense and eloquent expression of their lives.”

That statement may or may not be entirely true (the back and forth between rural and urban was arguably not quite as hard and fast as Crumb makes it out to be.) But the important point is that Crumb is making a distinction between Ma Rainey and Charlie Patton — and Patton is the one who is intense, who is eloquent, and who is “real”. In his appreciation of the form, then, Crumb has bypassed not only Janis Joplin but even Sarah Vaughn and her compatriots to arrive, at last, at the genuinely authentic expression of the blues.

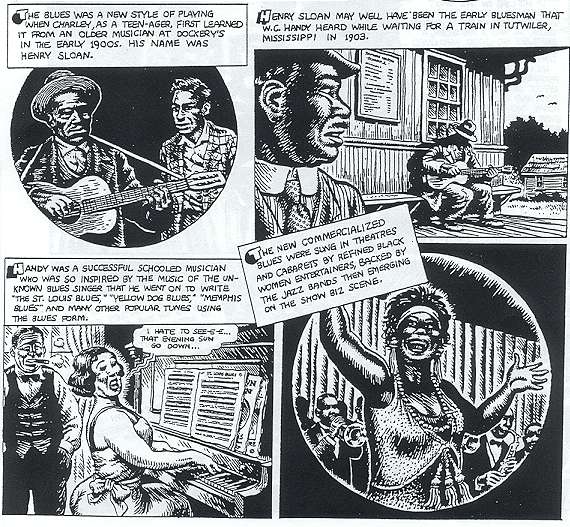

In “Patton”, appreciation is not passive contemplation; it’s more like passion or desire. Crumb, for example, shows two consecutive panels of men appreciating the playing of seminal bluesman Henry Sloan. First Charley Patton looks at Sloan with an intense, almost needy fascination; then W. C. Handy looks at Sloan with a glance that holds more surprise, but no less yearning.

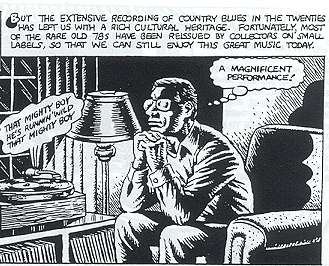

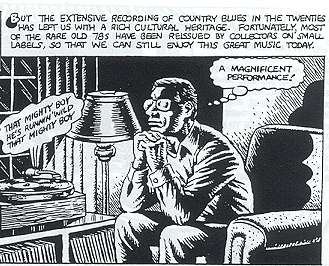

These meaningful stares are complemented a couple of pages later by this panel:

This doesn’t seem to quite be Crumb — his self-caricatures are generally instantly recognizable. But, at the same time, it clearly is Crumb; the white connoisseur who appreciates the “rich cultural heritage” of those African-Americans who (according to Crumb in the next panel) see the “old blues” as “too vivid a reminder…of an oppressive ‘Uncle Tom’ past they’d rather forget about.” Only the white listener can appreciate the lower-class, un-PC genius of the blues, undistracted by a history of oppression which regrettably (if understandably) blinds the music’s most direct heirs.

Of course, as we’ve seen, Crumb himself is responsible for at least one of the most widely disseminated modern examples of vicious Uncle Tom iconography in existence. Given that, it seems fair to wonder whether he isn’t protesting a bit too much here. Are black folks really disdainful of the blues because the music is not as uplifting as gangsta rap? Do they really see blues songs about violence, sex, and drinking as somehow Uncle Tomish? Or, you know, is the music just really old pop culture, and therefore not of particular interest to most people, as is generally the case with very old pop culture?

Perhaps the real question is not why black people don’t love the blues enough, but why Crumb loves it so much. After all, what is he getting from this story of authentic black people carousing and fighting and making great timeless art which only he and a select few like him understand?

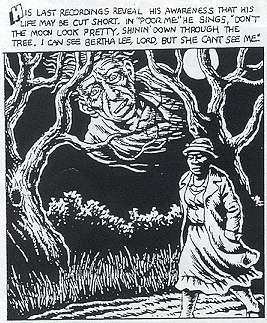

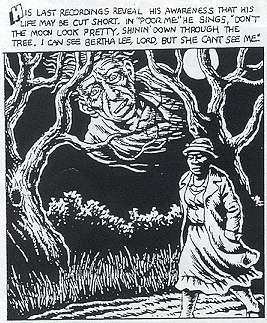

It’s not really that difficult a question, obviously. White American culture (and not just American), from Gershwin to Joplin to Vanilla Ice and Madonna (to say nothing of Elvis) has long been obsessed with adopting, miming, parodying, and exploiting black culture. Because they have been oppressed and marginalized, blacks have taken on a kind of totemic value; they and their culture are the ultimate expression of resistance to the man, of purity and heart in the face of a monolithic culture of indifference. Being black is being cool — and through his love of old blues, Crumb can be blacker than Janis Joplin, blacker than Bessie Smith, blacker than non-blues-listening African-Americans — blacker, in other words, than black. On the last page of the story, we see a ghostly Charlie Patton floating above his girlfriend Bertha Lee — and you have to wonder if that’s how Crumb sees himself, an intangible, unseen observer, both watching and inhabiting the long-dead African-Americans he animates and desires. We haven’t, after all, come that far from Cheap Thrills; it’s just that, instead of drawing blackface, Crumb has — circuitously and with less painful racist connotations, but nonetheless — donned it himself.

____________

Karen Green had a thoughtful comment at Comixology.

In fairness, Noah, the two gratuitously naked and/or nubile women you show in the Patton comic would likely have been gratuitously naked and/or nubile even if they were white woman. As a woman, I’m well aware of how Crumb prefers to depict us!

There’s no excusing the Cheap Thrills cover, however.

I think you’ve touched on something quite insightful, though, in concentrating on WHY Crumb loves the blues–especially to the extent that he loves it. There is clearly the love of the arcane, the elevation of self into a particularly rarefied aficionado. (And I would wager there are just as many African-Americans pursuing that arcane love of the blues as there are whites.) But there’s also a possibility that a man who grew up seeing himself as marginalized and miserable–regardless of how easy his life was in comparison to former slaves–might find something kindred in that music.

That possible sense of kinship is what makes the Cheap Thrills cover all the more distasteful. Like Al Jolson in blackface gleefully reading the Yiddish paper The Forvert in the film “Wonder Bar,” it’s as if Crumb has embraced that black experience but still wants to prove that he exists apart from it–a particularly unpleasant wink at the audience.

And I responded:

I’d agree that it’s hard to tease Crumb’s misogyny out from his racism. My point here isn’t that he’s racist rather than misogynist, but that his fetishization of women bleeds over and inflects his fetishization of Patton. (Through his emphasis on Patton’s sexuality, through the use of significant glances sexualizing the blues, etc.) I think you could argue that it goes the other way as well, though (that is, the fetishization of blackness as earthiness inflects his misogyny.)

Art doesn’t belong to anyone; there’s absolutely nothing wrong with white people being into blues. There is, as you say, though, something unpleasant in the way Crumb seems to want to set himself up as more in tune with “authentic” blackness than some black people — especially given his really unfortunate history with racist caricature.

_________

This is a belated entry in our roundtable on R. Crumb and Race.