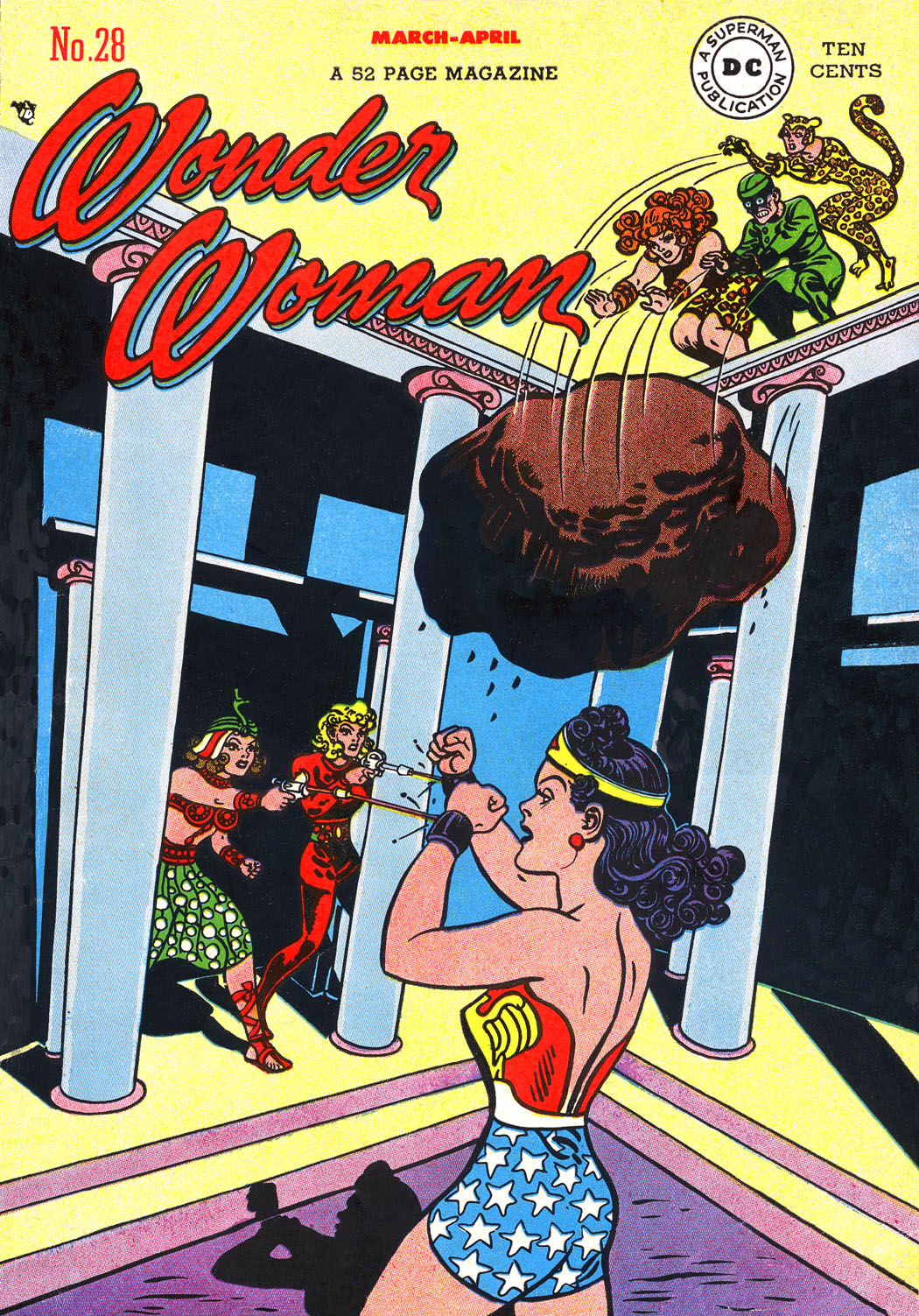

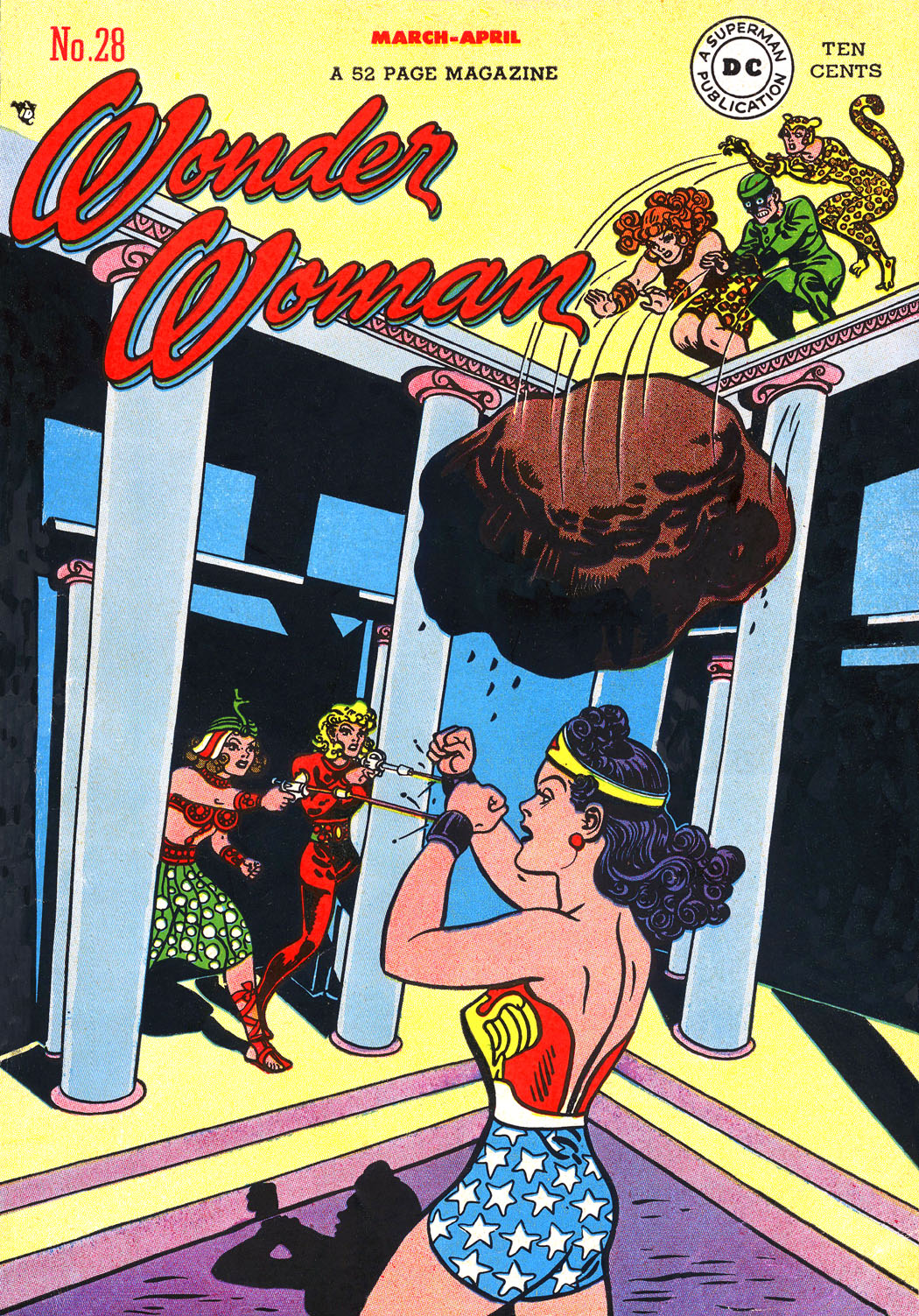

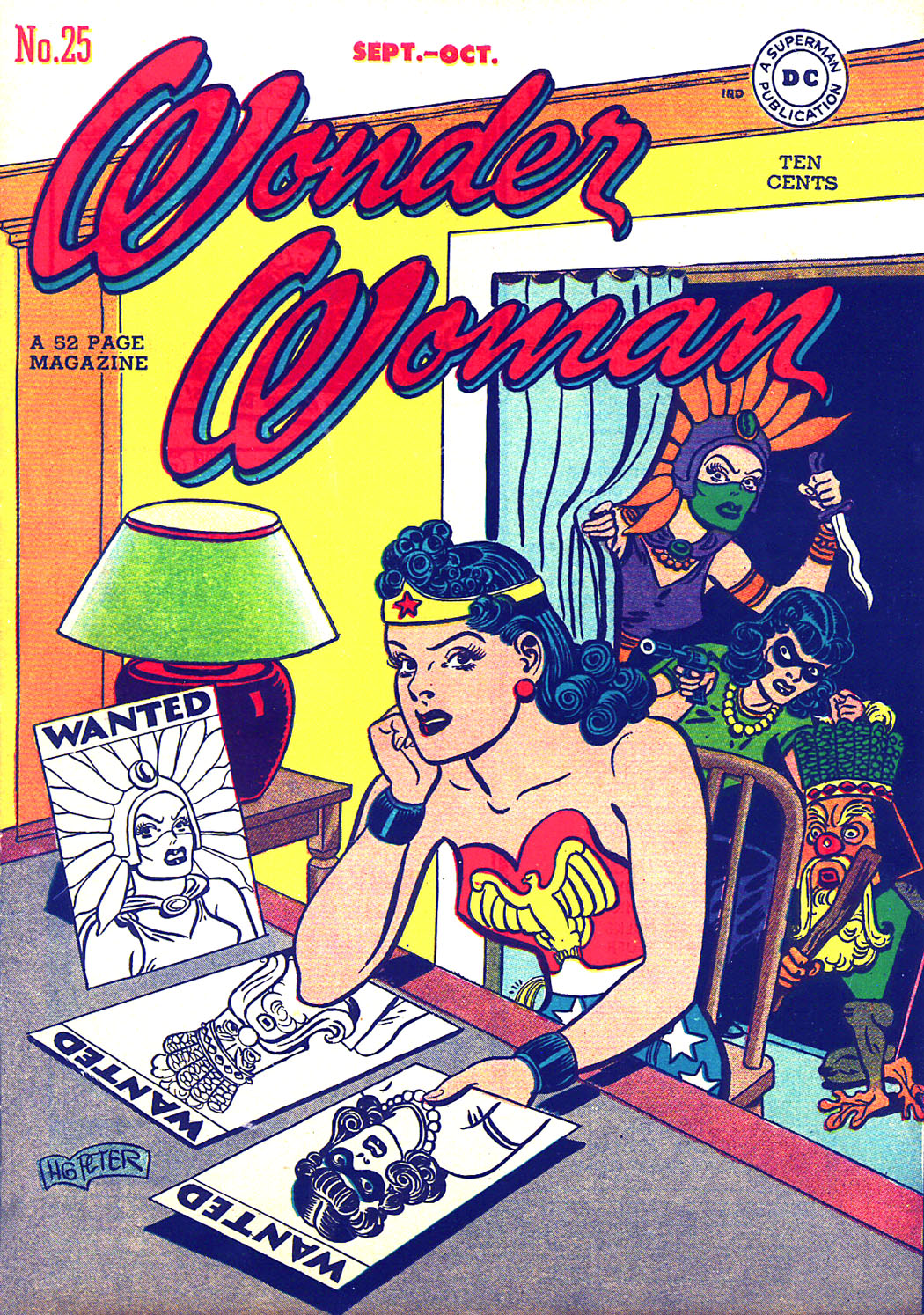

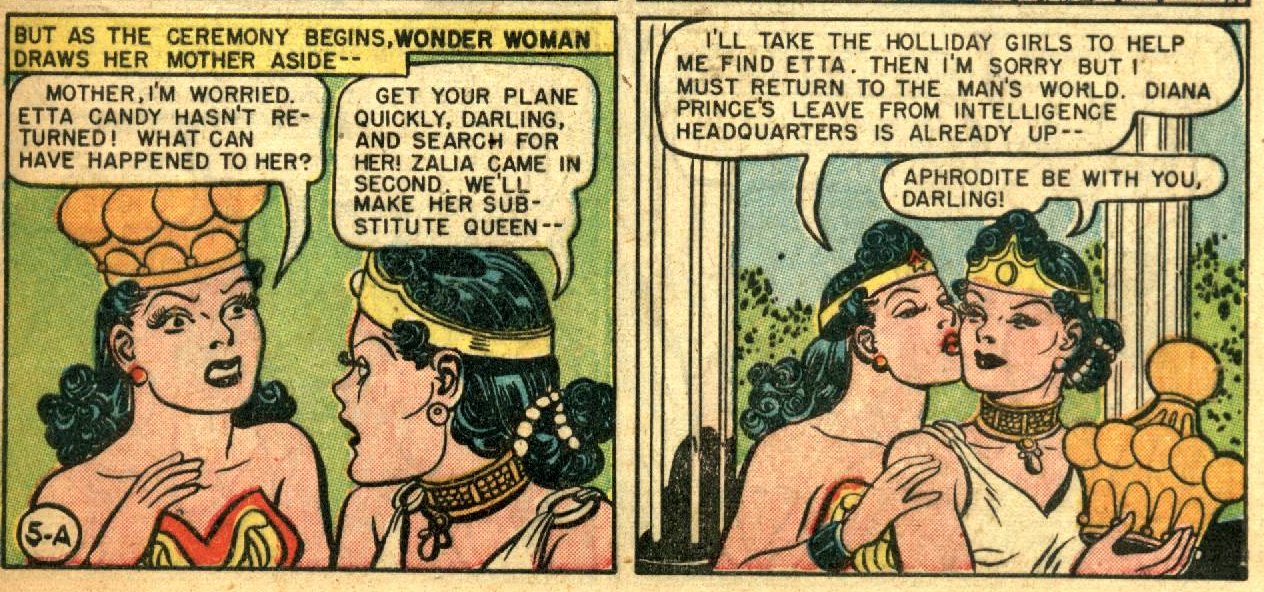

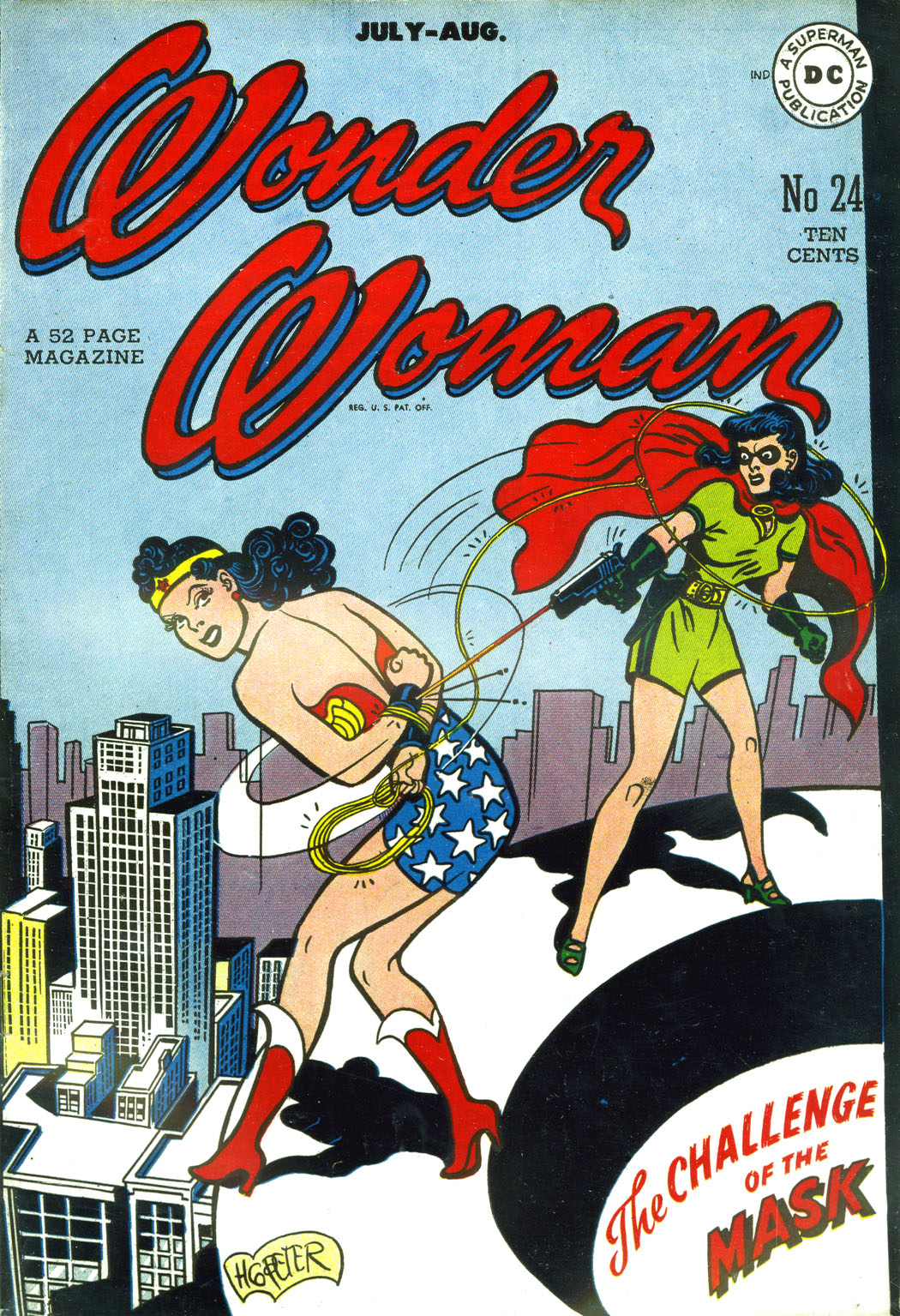

This is part of a roundtable on Marston/Peter’s Wonder Woman #28. The roundtable index is here.

___________________

I gave my son some Marston/Peter Wonder Woman comics…and he looooooves them. He’s especially into Etta Candy, who he thinks is just hysterical. And he’s right!

Anyway, at one point he said, “This must be written by a woman, right? Because all the characters are women.” And so I explained that no, it was written by a guy who just really believed that women were great — that they were better than men, even. Or as Marston said:

Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world. There isn’t love enough in the male organism to run this planet peacefully.

I didn’t bother reading that to my son, though. I just summarized.

In any case, my son wasn’t put out, though he did think Marston was a little confused. “Men and women are equal,” he said. “Neither is better than the other.” Gloria Steinem would’ve been proud.

Anyway, he brought it up again, I think after he read this issue, #28, from the Greatest Wonder Woman stories collection.

“Daddy, the guy who writes Wonder Woman thinks women are better than men, right?”

I said that that was the case.

“So how come all the villains are always women?”

It’s a good question…and one which incidentally seems to have flummoxed Gloria Steinem as well. It flummoxed her so thoroughly, in fact, that in a 1995 introduction to an Abbeville Press collection of Wonder Woman covers, she said:

Looking back at the post-Marston stories…I could see how littler her later writers understood her spirit. She became sexier-looking and more submissive, violent episodes increased, more of her adversaries were female, and Wonder Woman herself required more help from men in order to triumph. [my italics]

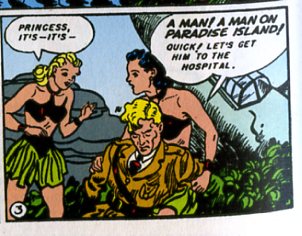

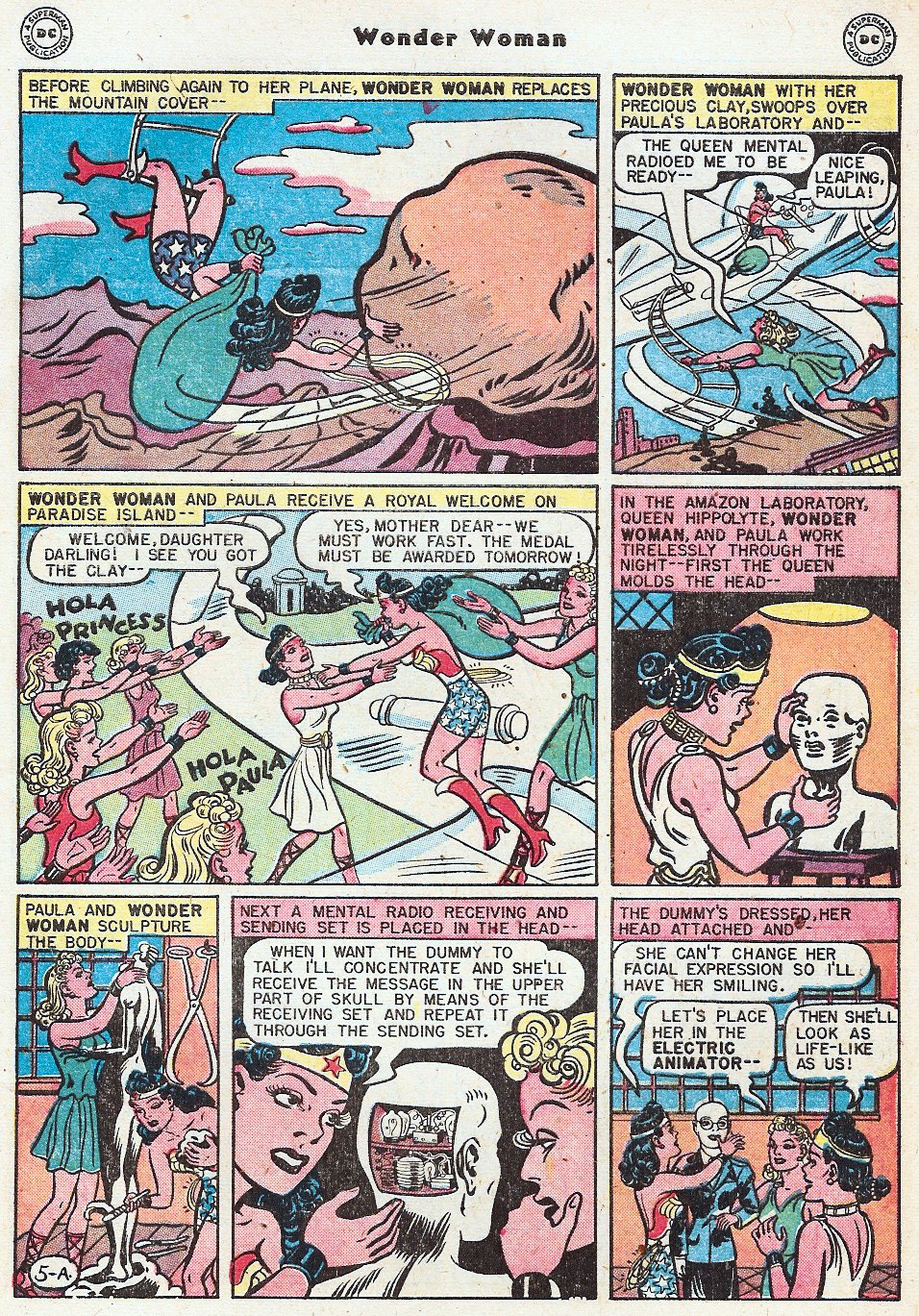

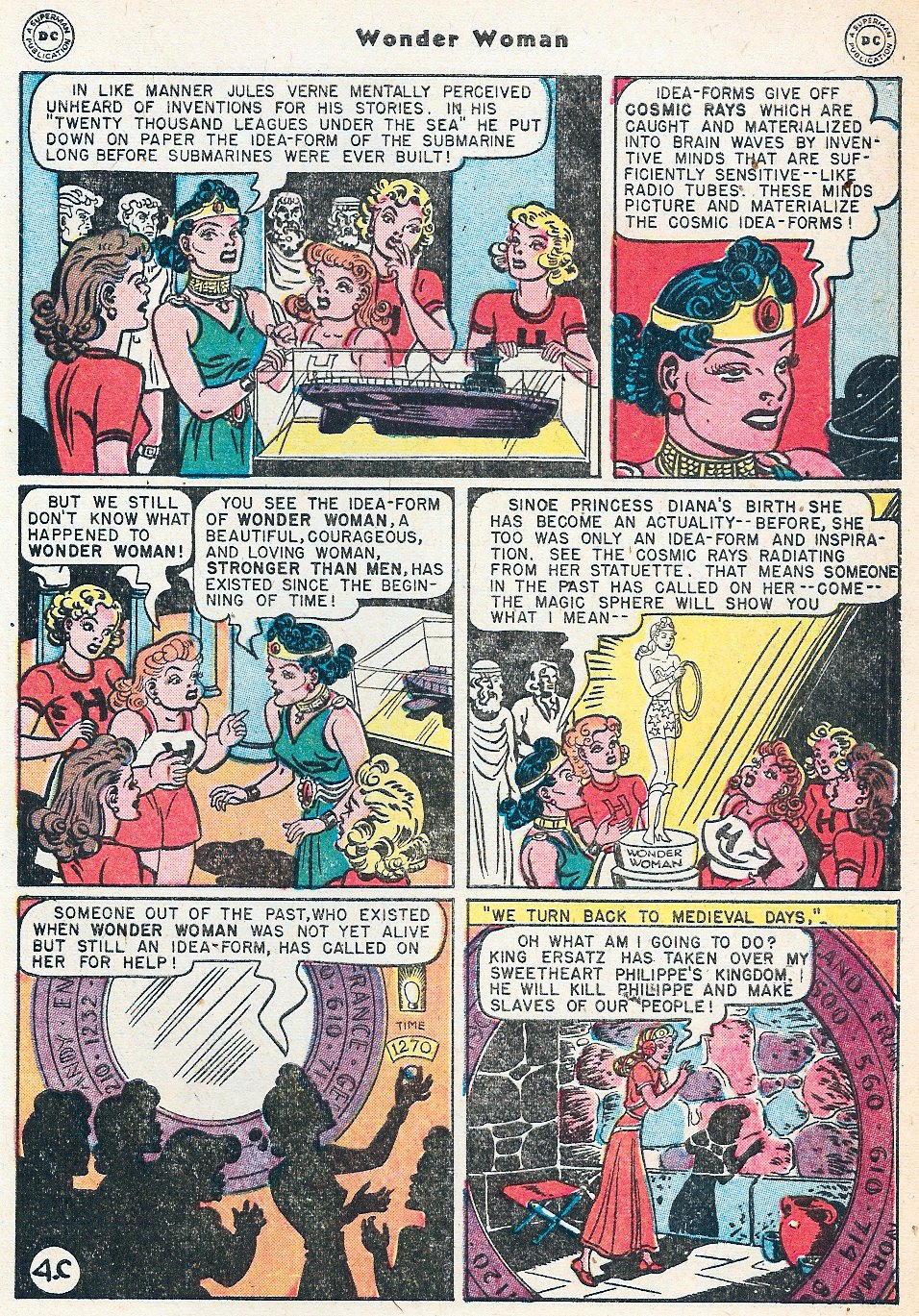

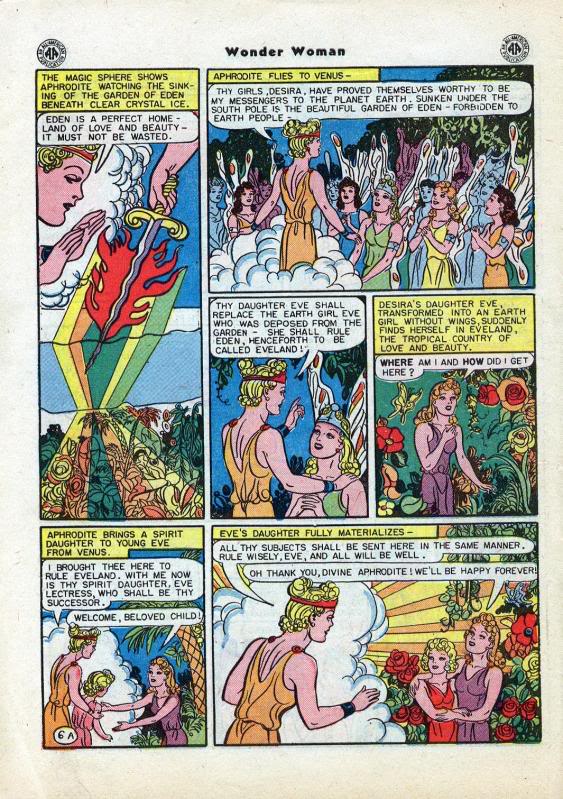

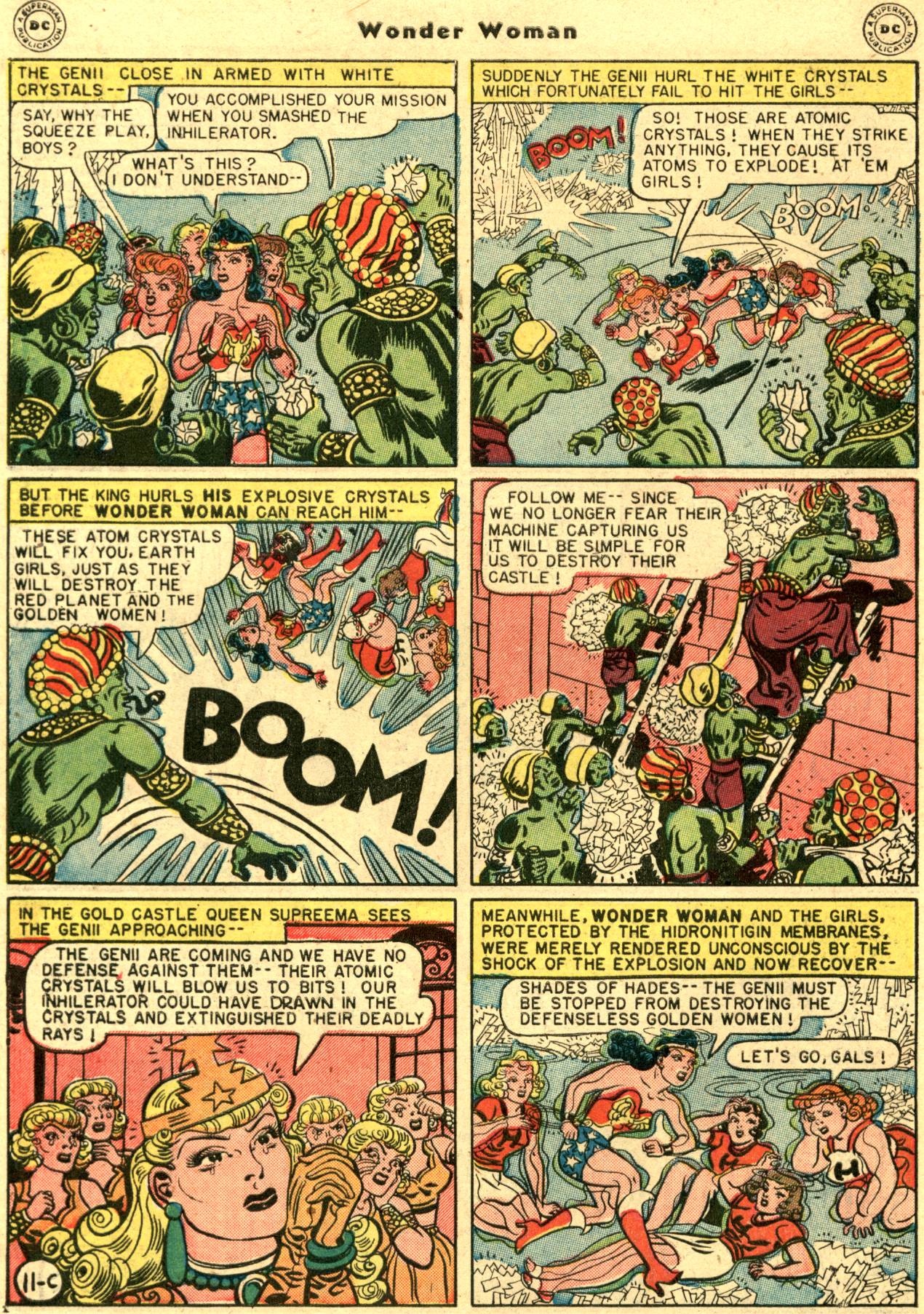

It’s true that Marston enjoyed creating the odd stunted male misogynist enemy (such as Dr. Psycho or the Duke of Deception). But I don’t see how you can read this issue and come away thinking that female antagonists, in whatever quantities, are unfaithful to his spirit.

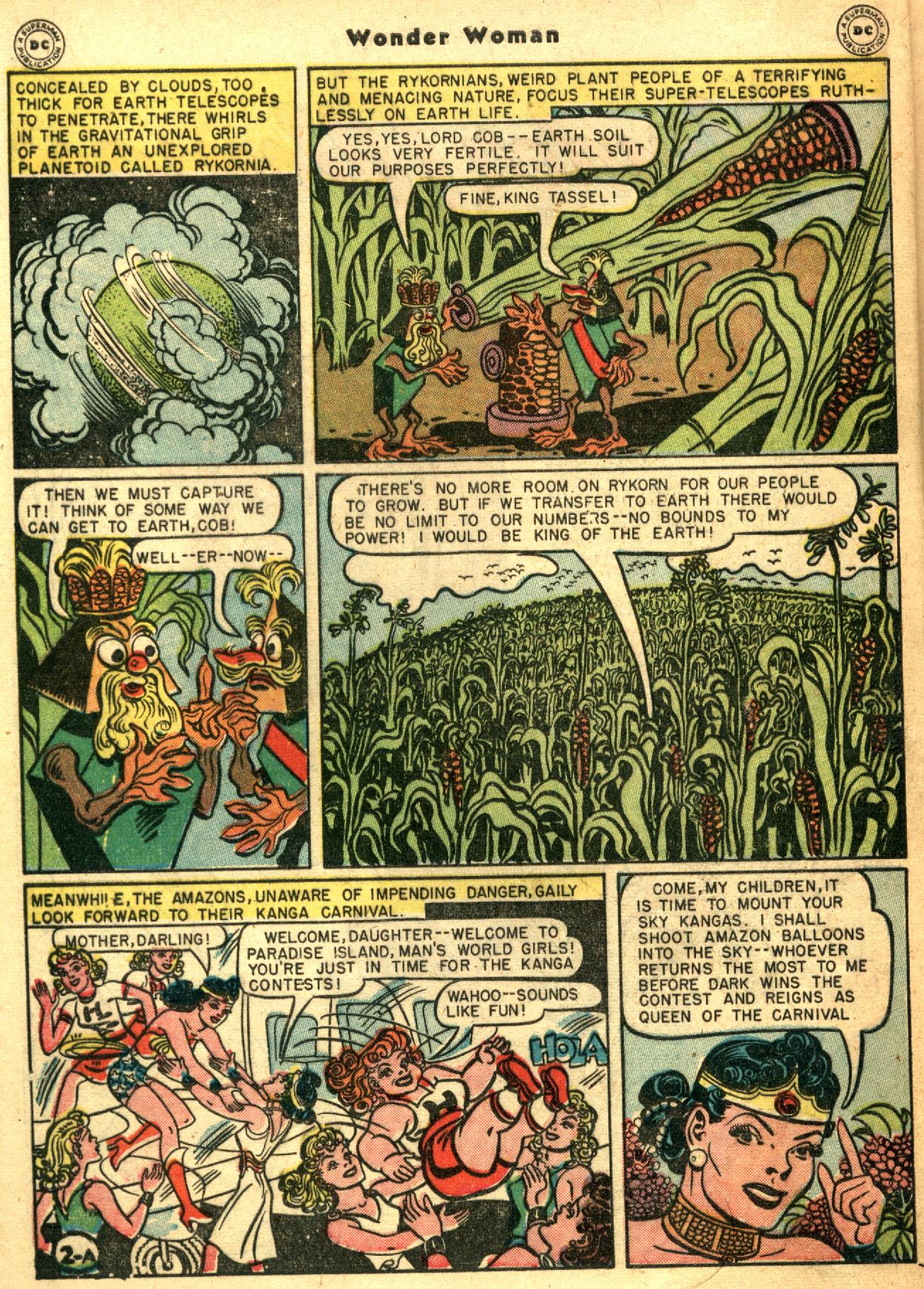

So how do female villains square with the idea that woman are superior — and superior precisely because they are peaceful and loving? What are all these peaceful, loving women doing running around trying to drop rocks on each other?

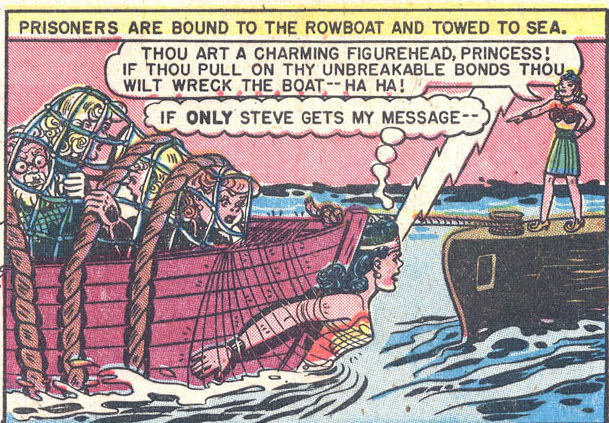

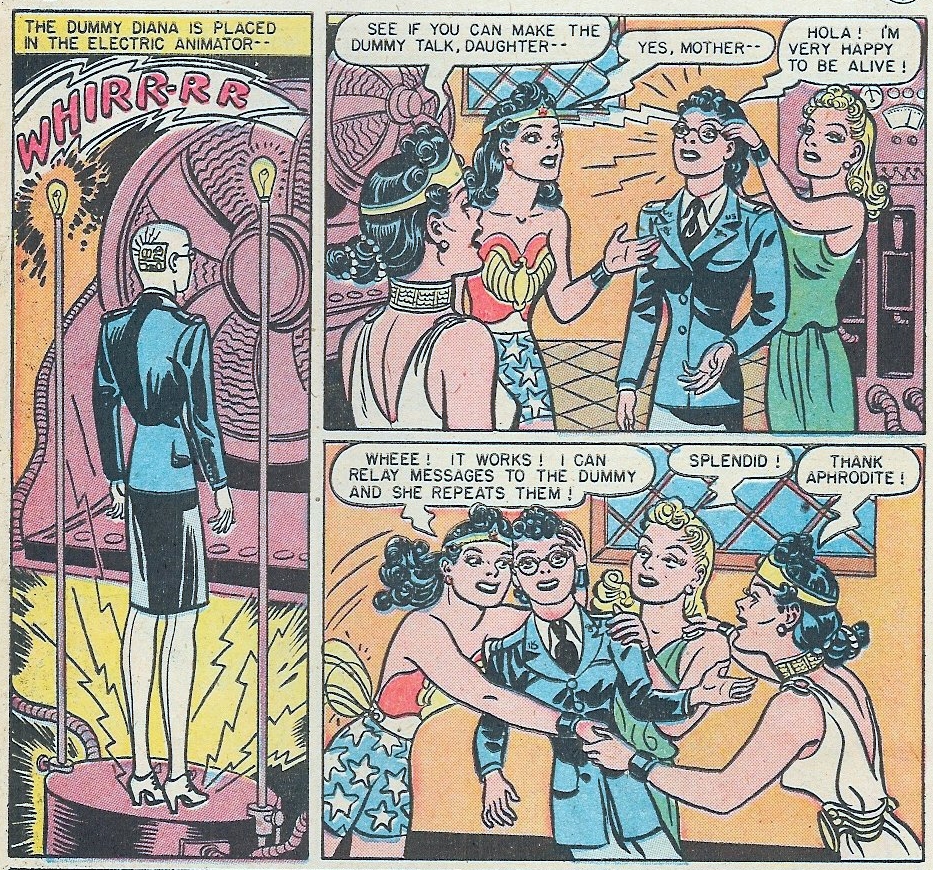

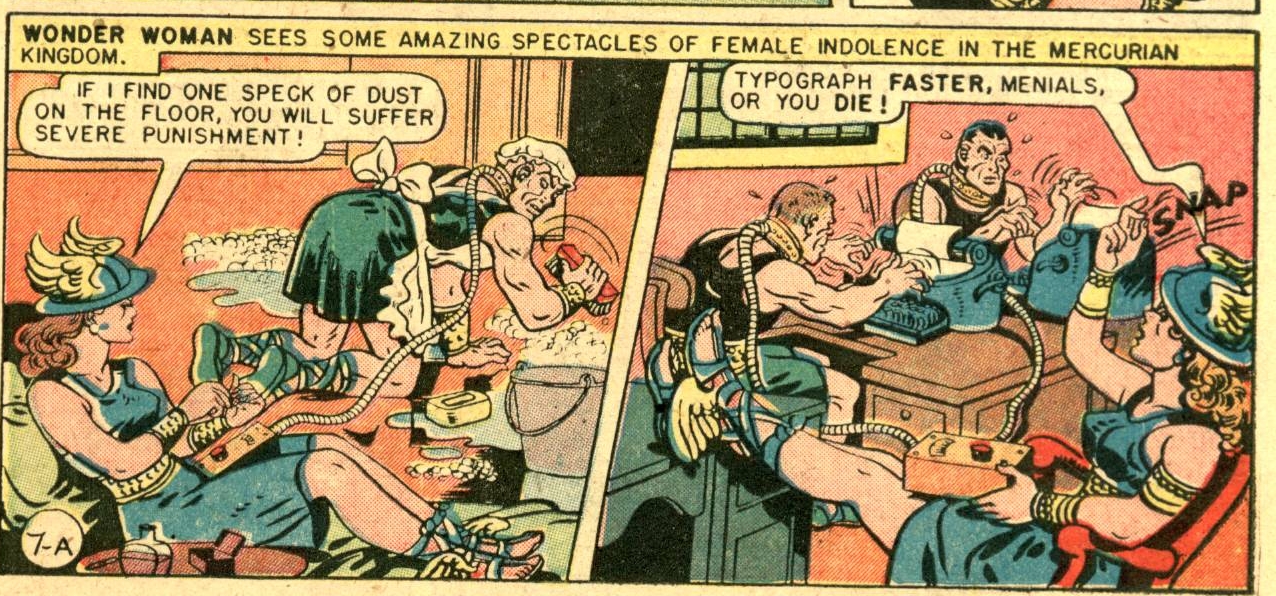

or devising bizarre bondage tortures for each other?

or devising bizarre bondage tortures for each other?

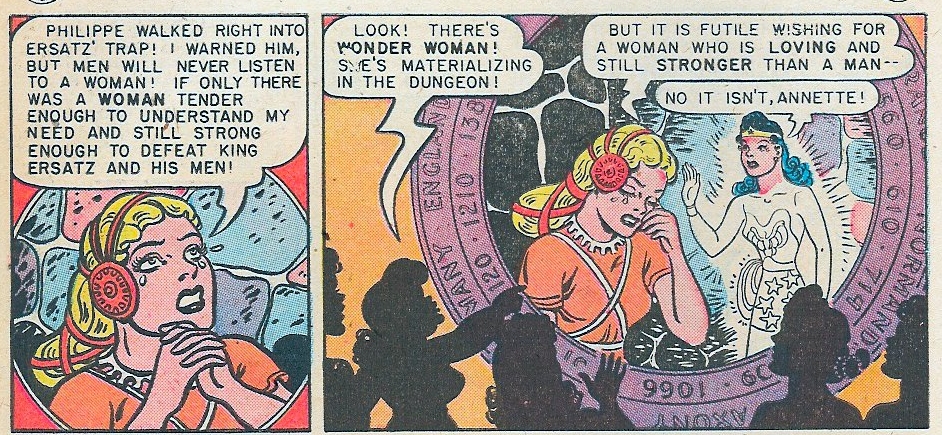

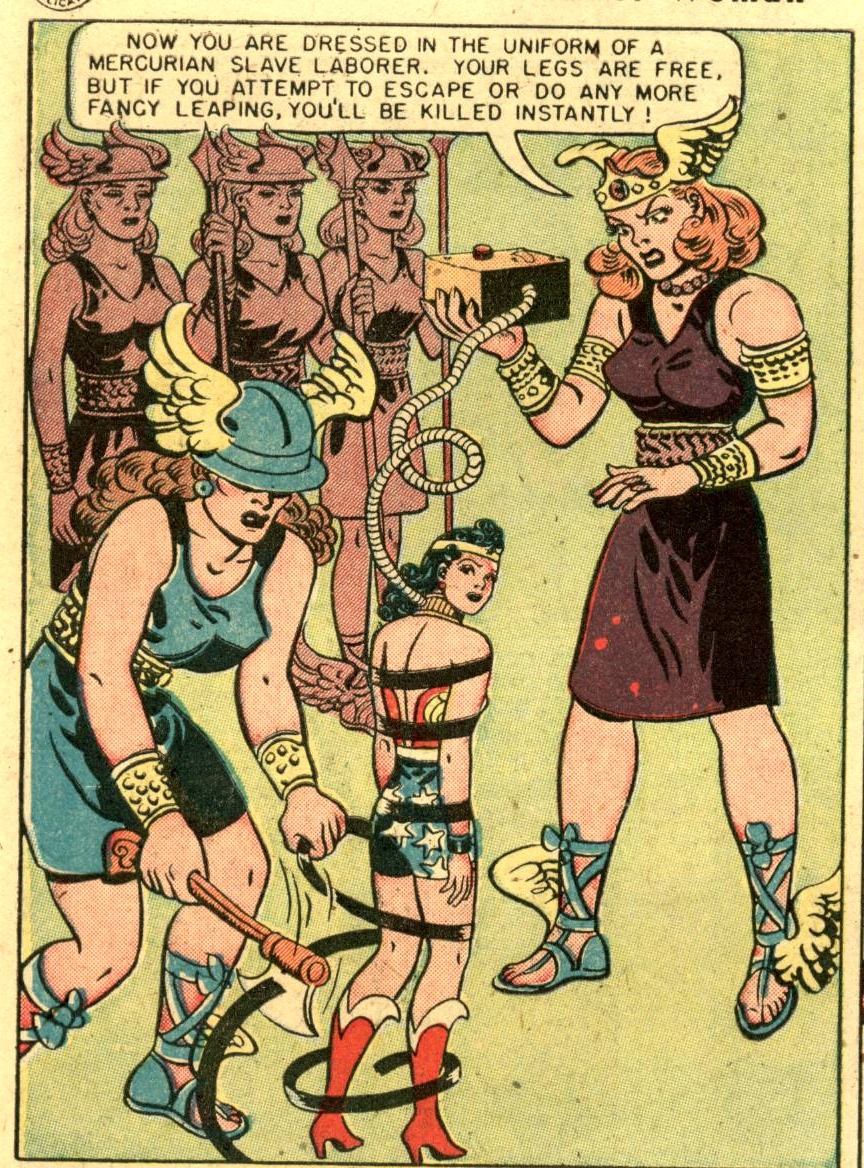

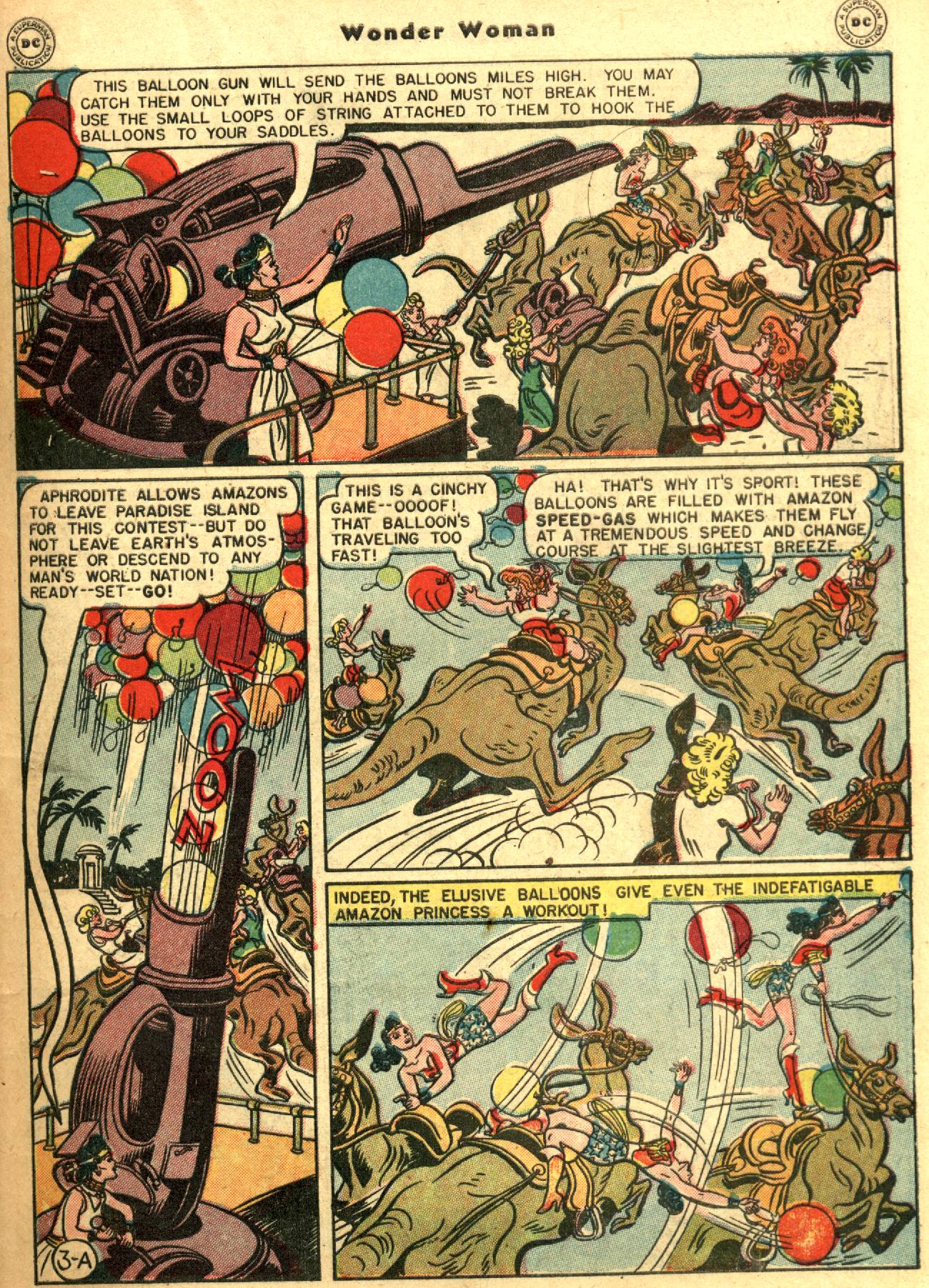

or, for variety, devising bizarre bondage torture for men?

I love that last panel. Clea and Giganta clustered shoulder-to-shoulder at the left merge into a single malevolent four-armed, two-headed feminine deity of castration, their mouths twisted into identical sneers of fury, those awesome Peter eyebrows flexing, and that blade aimed right where it’s aimed, with some adorable little effect lines to make sure we watch the point. And, of course, Steve at the right, with his shirt stripped off, is totally sexualized cheesecake. “Go ahead and heave your fun” indeed.

This is probably the sort of thing Gloria Steinem is talking about when, in an introduction to a 1995 collection of Wonder Woman covers, she gently chides Marston for being too masculinist.

Instead of portraying the goal of full humanity for women and men, which is what feminism has in mind, [Marston] often got stuck in the subject/object, winner/loser paradigm of “masculine” versus “feminine,” and came up with female superiority instead. (p.12)

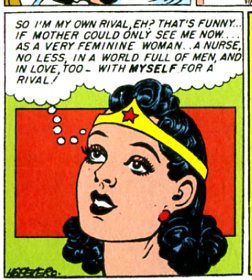

She’s certainly got him dead to rights here. Marston might as well be saying, “Hey, girls, you can do anything — even have torture/rape fantasies! Just like men!

The thing is…girls and women do in fact have torture/rape fantasies. And not just fantasies of being raped and tortured (as amply documented in Nancy Friday’s *My Secret Garden*), but fantasies of doing the raping and torturing. Tabico’s really extremely, NSFW fable about putting insects into the brains of her family members so she can have her sexual way with them is pretty extreme, but not isolated. Sharon Marcus in Between Women writes that during the Victorian era in England “fantasies of girls punishing dolls and being punished by them appeared regularly in fiction for young readers.” In showing women as sexualized aggressors, Marston was just giving girls the sorts of stories they had long enjoyed.

Of course, there’s no particular shortage of female, castrating villainesses in contemporary culture either. Here’s one:

In the new Wonder Woman, Azzarello and Chiang have their evil woman doing that thing that evil women do — using her sensual wiles to lure men into her clutches so she can cut their bits off. Women; their power is love gone wrong.

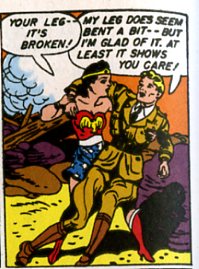

You’d think that would be Marston’s take too. After all, women are powerful because they understand love; ergo, if they are evil, shouldn’t they use the evil side of love and compel men with their dreaded Maxim poses?

Marston villainesses — in skin tight outfits and showing lots of skin — are clearly meant to be sexy. And he’s not adverse to having one or the other of them seduce Steve on occasion. But, unlike Azzarello’s Amazons, Marston’s villains are less likely use sex to gain the upper hand, and more likely to simply outgun, outfight, and outthink their male opponents. They don’t need to be shaped by male fantasies in order to be powerful.

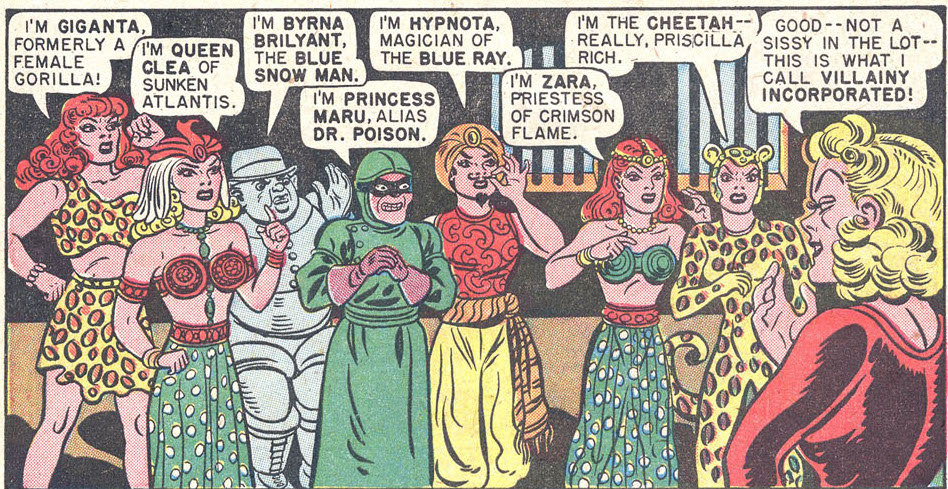

Perhaps this helps explain in part why Marston is so fond of cross-dressing villainesses.

You could see Byrna, Dr. Poison, and Hypnota as a nod to Marston’s misandry; men are evil, therefore women who are evil are manly — “not a sissy in the lot!” as Eviless declares. Still, while they may not be sissies, Zara and the Cheetah certainly can’t be said to be butch. Moreover, Marston goes out of his way to insist that the cross-dressing women are in fact women:

They may be able to pass, but that doesn’t mean they’ve cast their gender aside. You don’t have to wear certain clothes (or even be clean-shaven) to be a woman.

So why all the cross-dressing? Well, in the first place, Marston — who never met a fetish he didn’t like — probably found it sexy in itself. And of course it’s a metaphor for male to female cross-identification; many of Marston’s readers (like my son!) were boys identifying with a female hero.

But I think the cross-dressing could also be a metaphor for female to male cross-identification. It’s a winking acknowledgment that usually it’s boys who get to be roguishly evil, that usually it’s boys who get to be the mad scientists with their dripping needles or the mad hypnotists with their glowing eyes, controlling others not through seduction, but through force and evilness. Who hasn’t wanted to ditch the boring hero on occasion and be the scheming villain for a change? And if boys can do that, why not girls too?

All of which is to say…being bad. It’s fun. If you’re a kid and you have the choice between being powerful and good like Wonder Woman or powerful and irresponsible like Clea or Giganta, probably you’d choose Clea and Giganta, at least occasionally. Marston certainly believed in peaceful women and loving women. But he also believed in superior women, and if women are superior, then that means they’re not only the best heroes, but the best villains too.