Mort Meskin: Out of the Shadows, edited by Steven Brower. Fantagraphics Books.

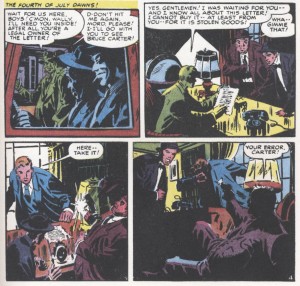

Mort Meskin’s studiomates in the bullpens of mid-20th century comics production remarked that he was a sensitive soul who was known to face a blank sheet with an artist’s block akin to sheer terror, until someone would scribble some random lines on the page, which he could then be sufficiently motivated to transform into his brilliant chiaroscuro images. Meskin’s best work was a powerful formative influence on other great comic book cartoonists such as Jack Kirby, Alex Toth, Steve Ditko and Jim Steranko. As the years passed, though, he became obscured in comics history. I was first made aware of him when he came up as I was interviewing Steranko. To identify the initiator of a comics storytelling technique, we consulted with the late, sorely-missed Dylan Williams, who had built a website about Meskin. Sure enough, MM turned out to have been the first to use the device in question, a Muybridge-like means of depicting rapid movement with multiple figures that Steranko called “strobing”. In more recent years, former Print magazine creative director Steven Brower has championed the artist, first with his 2010 Meskin biography Shadows to Light and now with a career-spanning collection of complete stories.

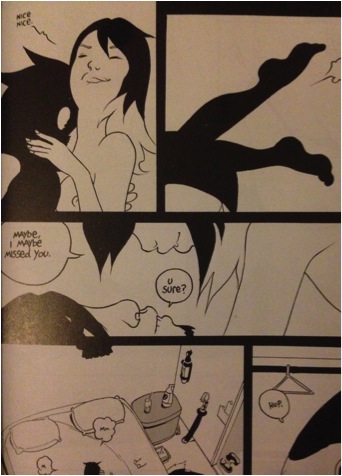

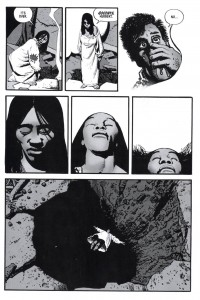

Meskin’s drawings seem to emerge from blackness

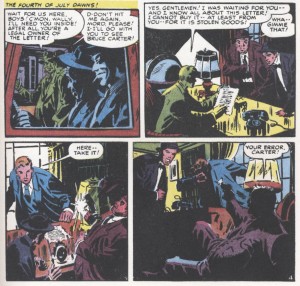

Some of his greatest early work in Out of the Shadows like Fighting Yank and collaborations with Jerry Robinson such as The Black Terror display particularly dramatic drawing and effective storytelling. In some of the stories, the color is unusually good; it is all wonderfully restored. Another highlight is that some of Meskin’s linework for Golden Lad is presented in incredibly crisp black and white. Sadly, there are no representations of Meskin’s work for his main client DC Comics on such inventive strips as Johnny Quick or even his later, apparently generic but no less animated and well-rendered short strips for their mystery and sci-fi titles, presumably because DC jealously protects its assets, even to the detriment of the legacies of its most innovative artists like Meskin and Toth. Still, it can be seen from Brower’s thoughtful selections that Meskin was a strong narrative draftsman and an architect of arresting images.

______________________________________________________

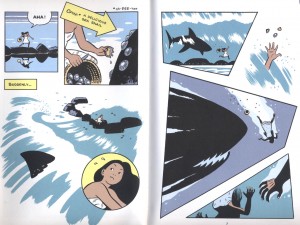

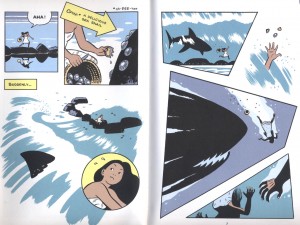

The Shark King by R. Kikuo Johnson. Toon Books.

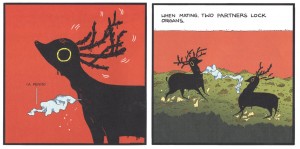

In this graphic novella produced under Francoise Mouly’s Toon imprint, Johnson appears as an heir apparent to Meskin and Toth. Adapted from a Hawaiian mythology, The Shark King reportedly truncates and makes more palatable its source story, but it is a sharply rendered and very effectively colored short children’s book that displays a tremendous amount of kinetic energy. The characters move around the pages in a manner which deliberately facilitates and enhances the reading experience. Johnson is a very clean and controlled artist who gives his book an almost “golden age” feel. His use of black and colors define the forms and spaces with a rare mastery.

Johnson’s color is apparently built from hand drawn separations.

I am a little unclear as to the value of the message the story sends boys regarding their relative relationships with their mothers and their willfully absent fathers, but still, I much prefer this book to Johnson’s earlier adult graphic novel effort, his beautifully brush-drawn but callow coming-of-age tale, The Night Fisher.

______________________________________________________

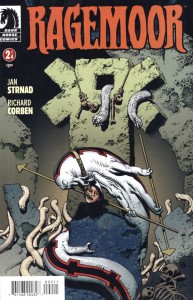

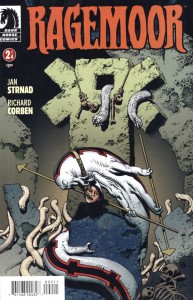

Ragemoor #s 1-4 by Jan Strnad and Richard Corben. Dark Horse.

In an interview on TCJ last week, Rich Corben speaks of his upcoming Edgar Allen Poe adaptations and honestly, I wasn’t overly excited by the news; I have a pile of his previous Poe work and enlarging it seemed to me to be a redundant reworking of relatively quiet, morbid tales that do not show off the artist’s best abilities. But maybe I should give him the benefit of the doubt. In recent years Corben has been doing a lot of work, some of the best of it in Mike Mignola-written Hellboy comics for Dark Horse. These have offered him ample opportunities to indulge in his trademark over-the-top horrific imagery, as well as the type of inventively articulated, muscular fight scenes that he excels at. And, although I admit I’d prefer that Corben colors himself, the Hellboys have been very well colored by Dave Stewart. I also admire a few stories that writer Jan Strnad and Corben did together in the past, but as their new miniseries Ragemoor came out over the past few months, it was a little hard to love.

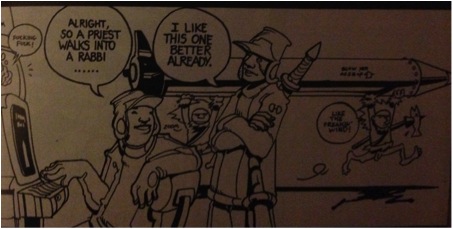

Perhaps the best art in the series, the cover to Ragemoor #2

For one thing, the art is black and white, not color and Corben does his own tones, but my initial impression was that the work here often looks a little awkward and rushed. His blacks are plenty juicy and his digital greys augment the maniacal depression that permeates the pages, but there is a chunkiness to the construction of the forms—a simplification of the drawing that often subverts Strnad’s scenario; it makes it quite difficult, for instance, to buy that the hero is smitten with the female character, who must be one of Corben’s least appealing ever for the pulpiness of her features…and that is saying something. He is known for constructing clay models to draw from, but here she seems smooshed by all thumbs. Yeesh!

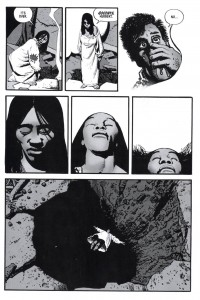

The “splendorous angel” Anoria takes a dive in Ragemoor #3

However, it wasn’t until I had all four issues that I was able to truly appreciate this effort. In the end, Corben doesn’t disappoint….it works much better taken as a whole than it did as a serial. So buy them and read them all in one sitting. There are some genuinely frightening moments, not least what becomes of the hideous heroine.

______________________________________________________

Prophet #22-26 by Brandon Graham, Simon Roy, Farel Dalrymple and Giannis Milonogiannis, with Fil Barlowe, Frank Teran, Emma Rios and others. Image Comics.

I have Brandon Graham’s thick King City book, although I haven’t yet had a moment to read the whole thing. I can say, though, that his solo comics strike me as one of the few times (Damion Scott is another) that I have seen a cartoonist whose work effectively evokes the imagery of Hip Hop, which through aerosol innovators like Phase 2 evolved from the graphic forms of Vaughn Bod

Graham recently took over the Rob Liefeld vehicle Prophet and is using it as a collaborative engine to work with other artists and in so doing to reinvent the esoteric science fiction promise of France’s Metal Hurlant, that has informed the cinematic science fiction of the past few decades but whose power disintegrated in the comics medium because of the mainstream American banalization of bad translations and airbrushed van-artiness of Heavy Metal.

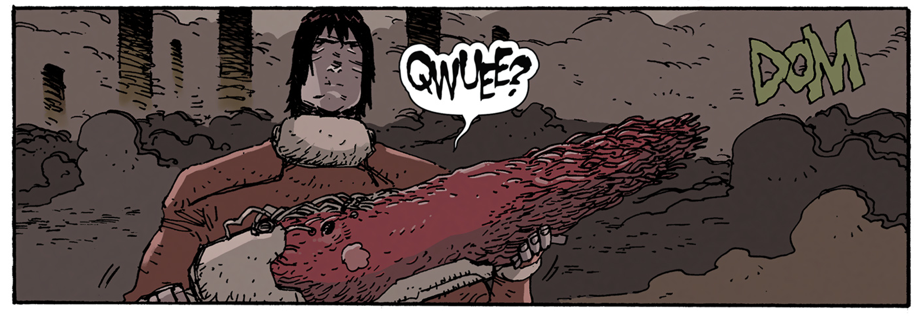

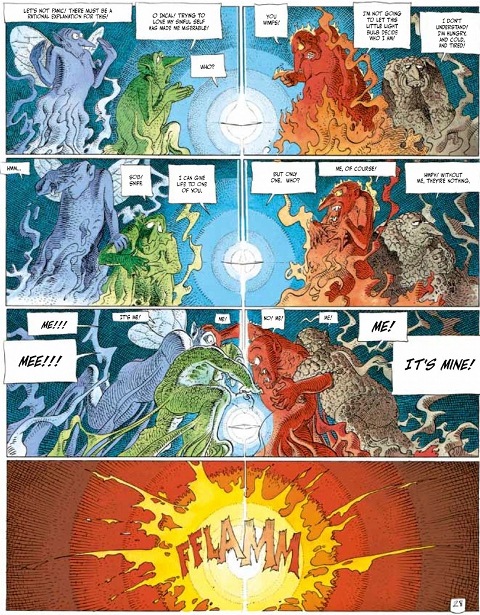

Graham and Dalrymple form a compelling argument for collaboration in Prophet #24

I have no idea what Leifeld did in his earlier issues of this title, but bless him for enabling us to jump in on Graham’s stories for Prophet, which are dark and forbidding but keyed to the unique properties of comics, written as they are to accommodate many double page spreads depicting far-flung vistas of more than passing strangeness and with odd diagrammatic passages that explain technical details. These disturbing scenarios have been drawn by a range of inventive talent, from several issues of Simon Roy’s fluid linework, to one with Giannis Milanogiannis’ slashing penstrokes, to one with some of the best work I have seen from Farel Dalrymple and then, the most recent issue is sparely drawn by Graham himself with echoes of Kirby and Druillet. All of the issues are beautifully colored. As the series goes on, an unusual sense of excitement, of discovery is engendered, a feeling that I have rarely had since my first exposure to Les Humanoïdes.

Graham draws his own script for Prophet #26

In addition, Graham has solicited some very interesting backup stories: #22 sported a short piece by the Australian Fil Barlowe, whose Zooniverse was a singular exponent of intergalactic multiculturalism in the early 1980s; #s 23 and 25 boast two parts of a Frank Teran strip and #26 has a piece by Emma Rios with an absolutely extraordinary panel configuration.

______________________________________________________

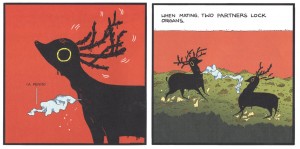

Spotting Deer and Lose #s 2-3 by Michael DeForge. Koyama Press.

I’m very encouraged when I see people such as Graham, Dalrymple and C.F. who seem to be influenced by sci-fi junk as much as anything and who are not afraid to work in genres that were formerly discredited by the alternative. Reality is fine as far as it goes, but comics also have potentials for world-building that aren’t scratched by stories about drinking coffee in cafes whilst bullshitting with one’s peers. Michael DeForge is another of the younger generation of cartoonists who uses sci-fi in his strips and this guy not only draws aliens, he draws LIKE an alien.

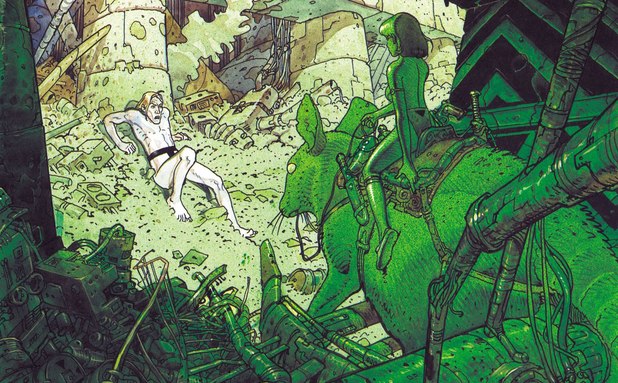

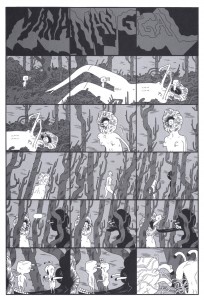

DeForge’s Spotting Deer: freaky deaky

His stuff reminds me a bit of my old friend Steven Cerio—-hmmmm…I wonder what happened to him?—like Steve, the work is bizarrely well-drawn while being frighteningly “othered” in conception. DeForge’s oddly shaped and thin but amazingly colored Spotting Deer book, for example, about a race of slug beings that mimic mammalian deer, is a real mindfuck prize and his erratic but engaging floppy comic Lose rewards examination, as well.

From Lose #3: nowhere to go but up

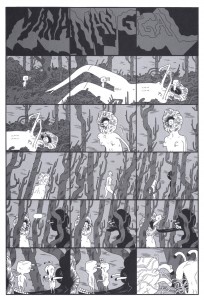

I don’t get why his main story in Lose #3 features an apocalyptic landscape with flying dogs who interact as if they are in a contemporary technological society, but it hardly matters; what counts is that DeForge uses the freedom of comics to make characters and places that follow his own rules. My favorite strip in this issue is “Manananggal”, a fearsome but indecipherable cinematic progression of otherworldly bioforms.

______________________________________________________

Raw Power Annual by Josh Bayer. Retrofit Books.

It can be difficult to explain to anyone, let alone someone not versed in the language of comics, the appeal of a Meskin, a Corben or a DeForge. I find it equally hard to describe Josh Bayer’s fierce comic Raw Power. I’ll try, though. I could say his massive figures bring to mind a sort of Kirby on amphetamines (and he milks and remilks a line from Jack’s “Street Code”), that the art seems sometimes as if it is drawn with a stick dipped in mud, but then, it also has some quite delicate passages and the entire thing reads with an invigorating, furious energy that is impossible to ignore. The story veers wildly; a description of Jimmy Carter’s war to suppress punk music (that I find completely believable and which was apparently imparted to Bayer by Jello Biafra and Ray Pettibone) segues from the origin of Bayer’s ultraviolent superhero Catman to a version of Watergate sociopath G. Gordon Liddy with the aspect of a fiendish motivational speaker and then goes into a revisioning of an issue of one of Marvel’s cheesy 1980s comics, DP7 (a little like Jonathan Lethem and Dalrymple’s reworking of Omega the Unknown), which I am certain is far more interesting than the original comic could have been.

Josh Bayer’s Raw Power: faster, harder, WTF.

Comics like these are why I still love comics—-they are full of the odd things that artists do that are personal tics, that perhaps are mistakes or maybe they are done on purpose, but they are what makes the stuff memorable and make us think that we also could make comics—-and we can! We can make them and print them ourselves! They are why, as I have discovered, the healthy part of comics is not in the pathetically over-edited and suicidal mainstream, but in the alternative where the artists, writers and readers are in charge. We can make lines coalesce on paper to form worlds in our own image and share them. We don’t have to answer to authority.

______________________________________________________