In his 1996 study Manhood in America: A Cultural History, Michael Kimmel describes the invention of the cowboy, a “mythic creation” with origins in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper; this creature of the nineteenth century imagination, as Kimmel points out, “doesn’t really exist, except in the pages of the western, the literary genre heralded by the publication of Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian in 1902” (Kimmel 149—150). Kimmel describes the hero of the western as a character who is “fierce and brave,” a man “willing to venture into unknown territory” in order to

tame it for women, children, and emasculated civilized men. As soon as the environment has been subdued, he must move on, unconstrained by the demands of civilized life, unhampered by clinging women and whining children and uncaring bosses and managers. (149)

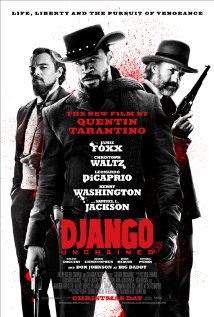

In The Virginian, and in the other novels, magazine serials, films, comic books, and television shows it inspired, this hero, of course, as Kimmel points out—a being who is “free in a free country, embodying republican virtue and autonomy”—“is white” (Kimmel 151). Quentin Tarantino’s new film Django Unchained, however, asks us to imagine a different sort of Western hero, one whose history returns us to the origins of African-American cinema.

Image from IMDB

Like Inglourious Basterds (2009), Tarantino’s new film is a vision of an alternate history. Jamie Foxx’s title character joins forces with Christoph Waltz’s German bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz on a series of adventures which culminate in the attempted rescue of Django’s wife Hildy (Kerry Washington). Unlike the characters Kimmel describes, Django is not running to the territory to escape the clutches of civilization. His journey is an inversion of the hero’s trajectory in the traditional western. At every step of the narrative, Django embraces civilization and demands the dignity which has been denied to him and his wife.

The fantasy of an escape into the wilderness, as Kimmel describes, was the invention of a writer from “an aristocratic Philadelphia family”; Owen Wister created a genre which “represented the apotheosis of masculinist fantasy, a revolt not against women but against feminization. The vast prairie is the domain of male liberation from workplace humiliation, cultural feminization, and domestic emasculation” (Kimmel 150). In Tarantino’s film, however, Django’s journey returns him to civilization, the violent, decadent world of Calvin Candie’s Mississippi plantation. It is not a feminized space which seeks to emasculate Django, but one of Candie’s henchmen, Billy Crash (Walton Goggins), in a hellish scene which alludes to the infamous torture sequence from Tarantino’s first film Reservoir Dogs (1992). This time the torture scene, stripped of the bloody glamour and outrageousness of Michael Madsen’s performance and the Dylanesque humor of “Stuck in the Middle with You,” is brutal and ferocious, a reminder to the audience of the horrific consequences of the plantation system for both the slavers and those who have been enslaved.

What animates the blood and the violence of this world? Greed drives Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie and his loyal servant Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson). In a sly reference to Greed, Eric Von Stroheim’s 1924 silent adaptation of Frank Norris’s 1899 naturalist novel McTeague, Tarantino’s Dr. King Schultz masquerades as a dentist, his wagon crowned with an enormous molar dancing on the end of a spring. In the logic of the film, greed is not a simple desire for wealth and property but is a form of anxiety caused by a perceived loss of control: Calvin fears he is not as wise as his father; Stephen is afraid of the new world Django represents. Both Calvin and Stephen are terrified of the freedom which Jim Croce celebrates in “I Got a Name” (written by Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox), the 1973 hit which provides the soundtrack as Schultz and Django ride out the winter and collect the bounties which will enable them to return to Mississippi to rescue Hildy: “And I’m gonna go there free/Like the fool I am and I’ll always be/I’ve got a dream/I’ve got a dream/They can change their minds but they can’t change me.”

Django is not searching for freedom from the feminized spaces Kimmel describes. Instead, Django’s journey is one of return, of reclamation. He is a western hero who abandons the John Ford-like expanses of the territory, which, as figured by Tarantino, are a series of illusions: over the course of the film, sometimes within the same sequence, Django journeys from what appears to be the deserts of the southwest; to the Rocky Mountains; to the live oak trees and bayous of Louisiana; to the mud-clotted streets of a Jack London-like frontier town (with Tom Wopat, Luke Duke from The Dukes of Hazzard, as the Marshall); to the hills of Topanga Canyon, the backdrop of most of the westerns filmed for American television in the 1950s and 1960s.

In Tarantino’s imagined southern landscape, Mississippi is just miles away from the golden hills just outside Los Angeles, and those hills are filled with extras from the Australian outback. As Candie and Stephen employ every means of violence and torture at their disposal to protect Candyland, Django comes to understand that the stability of place is an illusion; what is real is the world which has been denied to him, the vision of his wife Hildy which repeatedly haunts him until he finds her again in Mississippi.

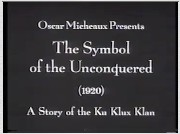

There is a long history of African-American westerns, dating back to the late teens and early 1920s. Like Django Unchained, these early films reverse the trajectory of Wister’s original myth, but movies like Oscar Micheaux’s 1920 The Symbol of the Unconquered should not be called revisionist westerns. Instead, both films, like their heroes, make demands on the genre itself: if the western is a form which celebrates freedom, Tarantino and Micheaux suggest, what better hero than an African-American fighting the evil embodied by the Ku Klux Klan? Pioneer African-American filmmaker Micheaux’s silent masterpiece, which was restored in the 1990s, can now be seen on YouTube with Max Roach’s masterful score (for more on the restoration of the film, see Jane M. Gaines’ Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era, page 331, and Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence’s Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences).

Image from The Museum of African American Cinema

While Hugh Van Allen (Walker Thompson) is the hero of The Symbol of the Unconquered, Eve Mason, the heroine portrayed by the luminous Iris Hall, is the focus of most of Micheaux’s attention. Having inherited a plot of land from her grandfather, “an old negro prospector,” she “leaves Selma, Alabama, for the Northwest” in order to “locate the land.” When she arrives, she falls in love with Van Allen, a black homesteader whose property borders her grandfather’s land. The subtitle of the restored version of the film, “A Story of the Ku Klux Klan,” indicates the dangers Eve will face as The Knights of the Black Cross threaten Van Allen. When the film’s villain, Jefferson Driscoll (Lawrence Chenault), discovers that Van Allen’s property possesses tremendous oil reserves, he enlists Old Bill Stanton to drive the black homesteader away.

Warned of the impending danger, Eve promises, “I’ll ride to Oristown and bring back help.” A title card then asks us to imagine “The infernal ride” as Eve returns in what appears to be a rodeo costume. In her fringed buckskin jacket and white hat, she mounts a horse and rides in daylight, as Micheaux cuts to images of the hooded knights, riding in darkness, their torches blazing, their faces eerie and obscure. In the fragments of the film which are left to us, it is impossible to tell if they are pursuing her, or if they are gathering to torch Van Allen’s tent; the climax of the film in which, as the title card tells us, these midnight riders are “annihilated” is also missing, but the resolution of the story remains intact. Eve and Van Allen, now an oil baron, fall in love and, in the movie’s final scene, embrace.

The most powerful image of Micheaux’s film is not this final embrace but the shot of Eve Mason on her horse, riding furiously to Oristown to raise the alarm. Like Django’s journey, hers is a return, and her presence is a demand, not for control but for justice. While the white cowboy’s privilege lies in his ability to choose between a quiet life in civilization or an escape to the territory, Django and Eve exist in a world in which this choice has been denied to them. They must reclaim the ability to make this choice, and when they do so, both choose in favor of the domestic spaces which inspired them to take this “infernal ride” in the first place. Perhaps, then, we can read both Django Unchained and The Symbol of the Unconquered not as westerns but as comedies in the Shakespearean sense, in which the forces of evil are contained, and a world of chaos is redeemed as our heroes—and heroines—marry their beloveds and, like dime-novel cowboys, ride off into the sunset.

References

Django Unchained. Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Perf. Jamie Foxx, Christoph Waltz, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kerry Washington. The Weinstein Company, 2012. Film.

Gaines, Jane M. Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. Print.

Kimmel, Michael. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: The Free Press, 1996. Print.

The Symbol of the Unconquered. Dir. Oscar Micheaux. Perf. Iris Hall, Walker Thompson, Lawrence Chenault, Mattie Wilkes, E.G. Tatum. 1920. Film.