Bliss was it to be alive in that dawn,

But to be young was very heaven!

—Wordsworth

A house in Launceston Place, Kensington, London; we were a couple of doors down.

In 1969, my family moved to London; in December of that year, I turned 15.

London– 1969– 15 years old?

Yesss!!!!

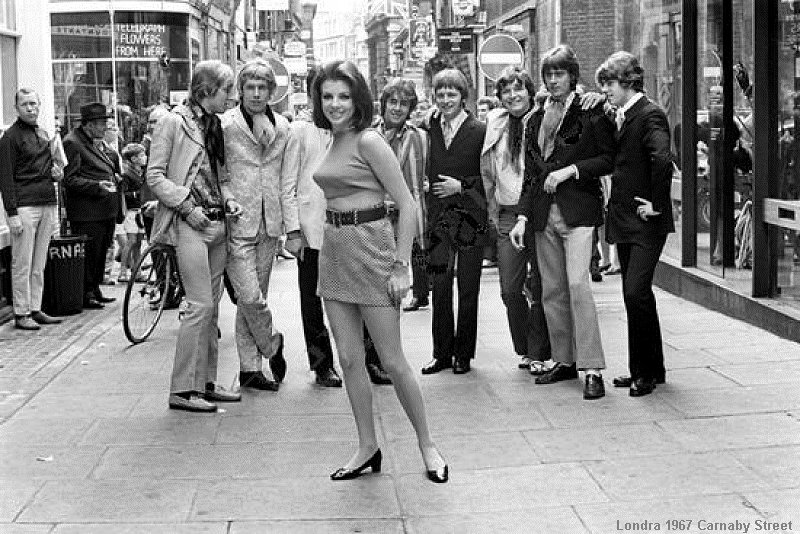

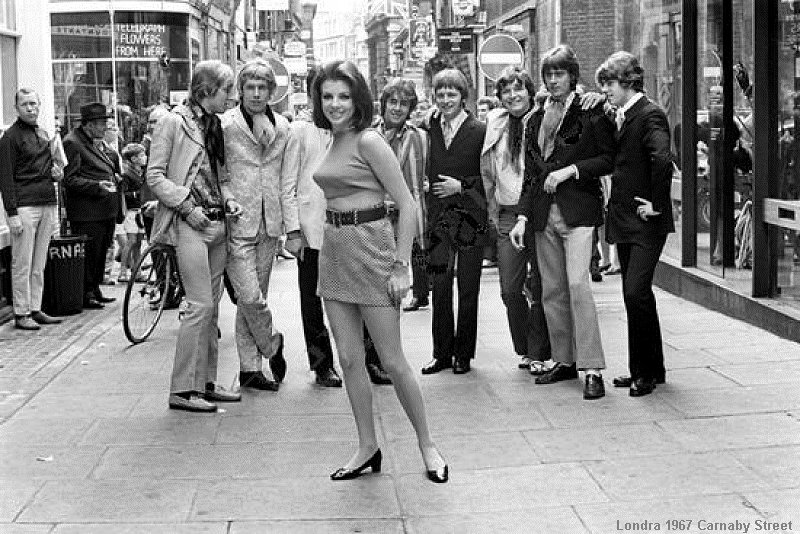

“Swinging London” was still very much roaring along. Behold Carnaby Street, luv:

I’d come from a deeply repressive Swiss all-boy Jesuit school the year before, where tracts against masturbation were solemnly handed out, and attending a party featuring ‘impure’ pop music was grounds for expulsion.

And here– just in time for my puberty– was I introduced to this carnival, this opportunity to blossom!

Soon I’d ditched my staid flannel tartans and chino trousers for paisley scarves, ruffled pink shirts, and bell-bottom pants…

That’s me, age sixteen, literally rising above my peers at school.

The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix (who died in the hospital next door to our first house — for some reason that spooked me at the time), The Mothers of Invention, The Rolling Stones…they furnished the soundtrack to my life.

Ah, but this is a column about comics, is it not? So what was the scene like at the dawn of the ’70s?

It was glorious.

Current wisdom holds that comics of the ’70’s were in a particularly dire patch of their history; but this sad state of affairs came about essentially after 1973, and there were bright spots even so until the end of the decade.

The comics Underground was at the apex of its short history; Crumb, Shelton, Deitch and co. Their comics were hard, but not impossible, to find in London; generally in the funkier record shops like Cheapo Cheapo Records off Picadilly, or in the patchouli-scented head shops.

Mostly, though, they were reprinted in underground newspapers like the International Times (IT):

click image to enlarge

The British Underground comics scene was pretty underdeveloped, though there were promising exceptions. Here, from IT, is Michael Moorcock‘s Jerry Cornelius, as rendered by Mal Dean:

click image to enlarge

An all-comics offshoot of IT was Nasty Tales, edited by the musician Mick Farren. More Crumb than you can shake a stick at:

… and it was a Crumb spread of an orgy that caused the publisher to be prosecuted in the sensationalised trial that set a precedent for freedom of the press. A benefit comic was published, with early work by Dave Gibbon:

Meanwhile, across the Channel, French comics were enjoying something of a golden age; magazines such as Pilote and Charlie were moving to more adult content.

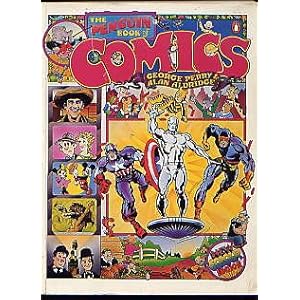

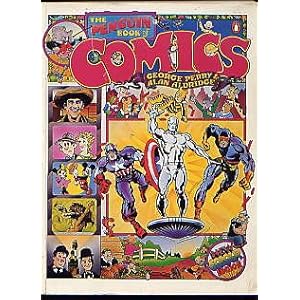

That 1969 Christmas, my father gave me a book that was a touchstone for an entire generation of fans: The Penguin Book of Comics, by George Perry and Alan Aldridge:

My collecting centered mostly on the American mainstream: Marvel, DC, Warren.

At first, American comics were distributed in the UK in a very haphazard manner.

They were mostly unsold copies from the USA that were shipped across the Atlantic as ballast. You never knew what you’d find: that ensured the thrill of the hunt all collectors know.

It was a rich period in the mainstream. The old-guard cartoonists– Kirby, Adams,Wood, Severin, Kubert, Heath, Kane and so on– were at the top of their powers, and were joined by a crew of young Turks of remarkable talent– Barry Smith, Mike Kaluta, Berni Wrightson, Frank Brunner, Ralph Reese, Howard Chaykin.

Popular genres other than the super-hero were still flourishing: war, mystery/horror, romance, fantasy. There was still a plethora of humor books.

And an innovation that foretold the future of comics as we know it was coming into being: the comics shop.

click image to enlarge

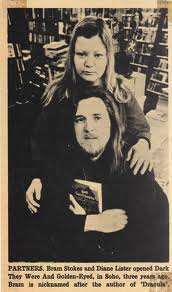

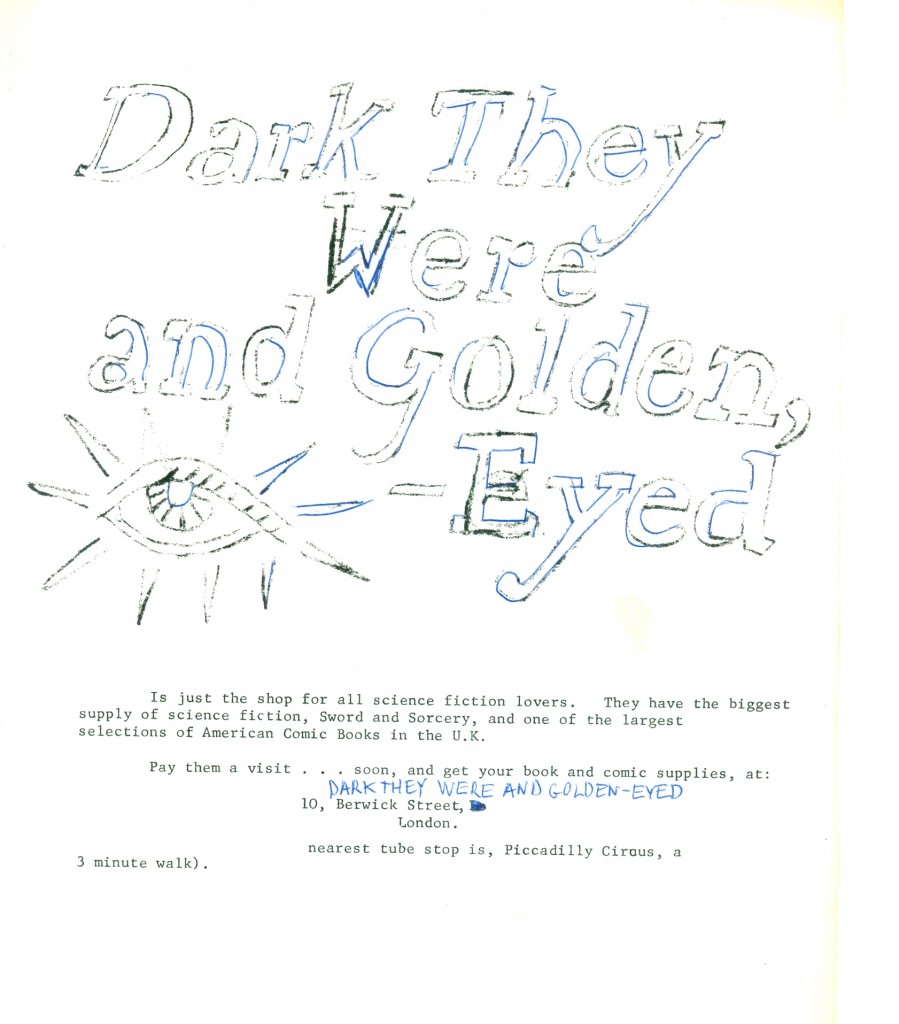

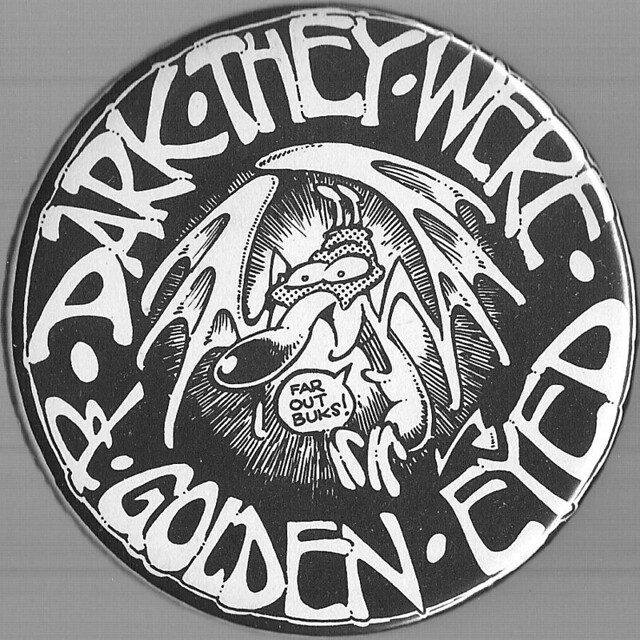

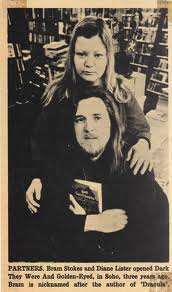

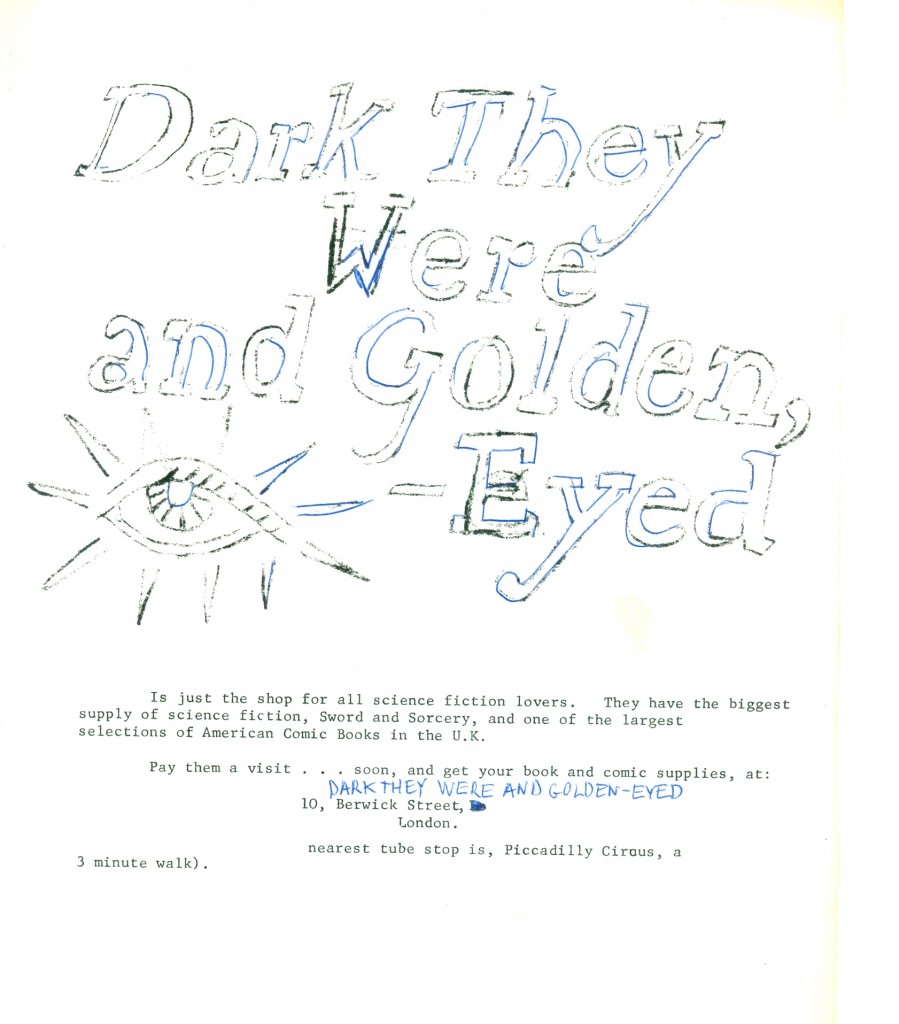

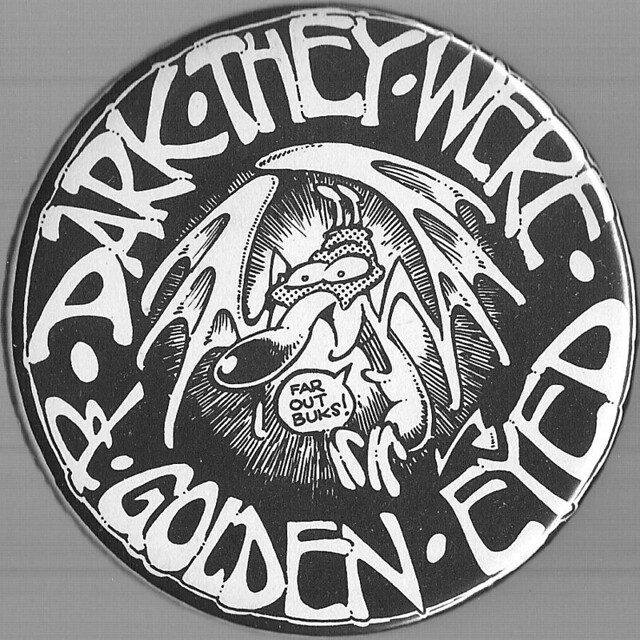

When I first opened the door of ‘Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed’, Britain’s first comics store, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. A shop given over entirely to comics? Was it possible? Was it even legal? It was indeed.

Derek ‘Bram’ Stokes and Diane Lister…for ten years the priests of London’s comics temple

And for the first time, I was meeting other comics lovers there: I had discovered fandom. And with fandom, fan publishing.

In those pre-Internet days the main medium of communication for comics lovers was the fanzine. Britain had its fair share of ‘zines, such as Rich Burton’s Comic Media News or Frank Dobson’s and Dez Skinn’s Fantasy Advertiser.

Yes, breathes there a fan with soul so dead that to himself has never said, ‘I think I’ll start a little fanzine’?

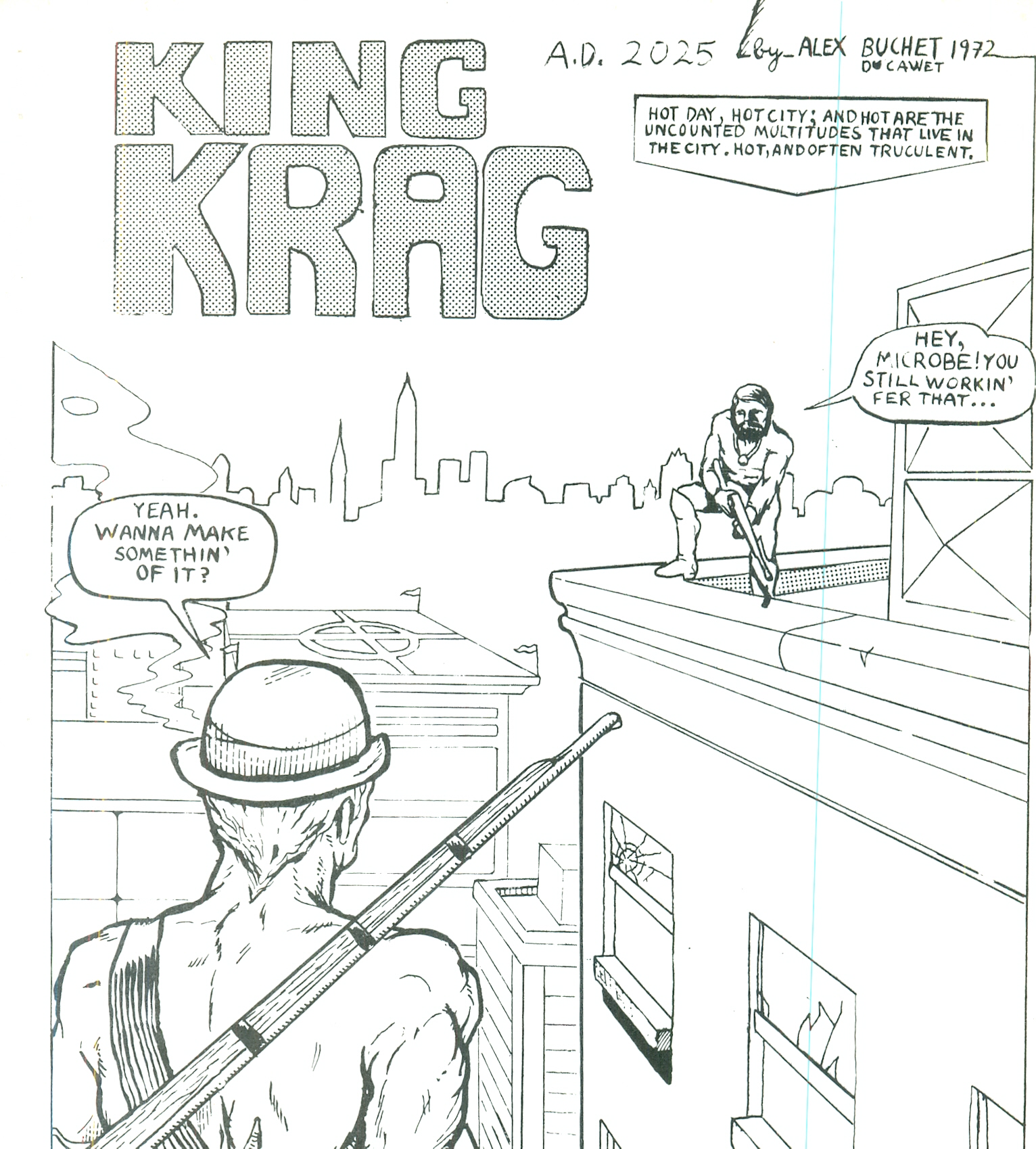

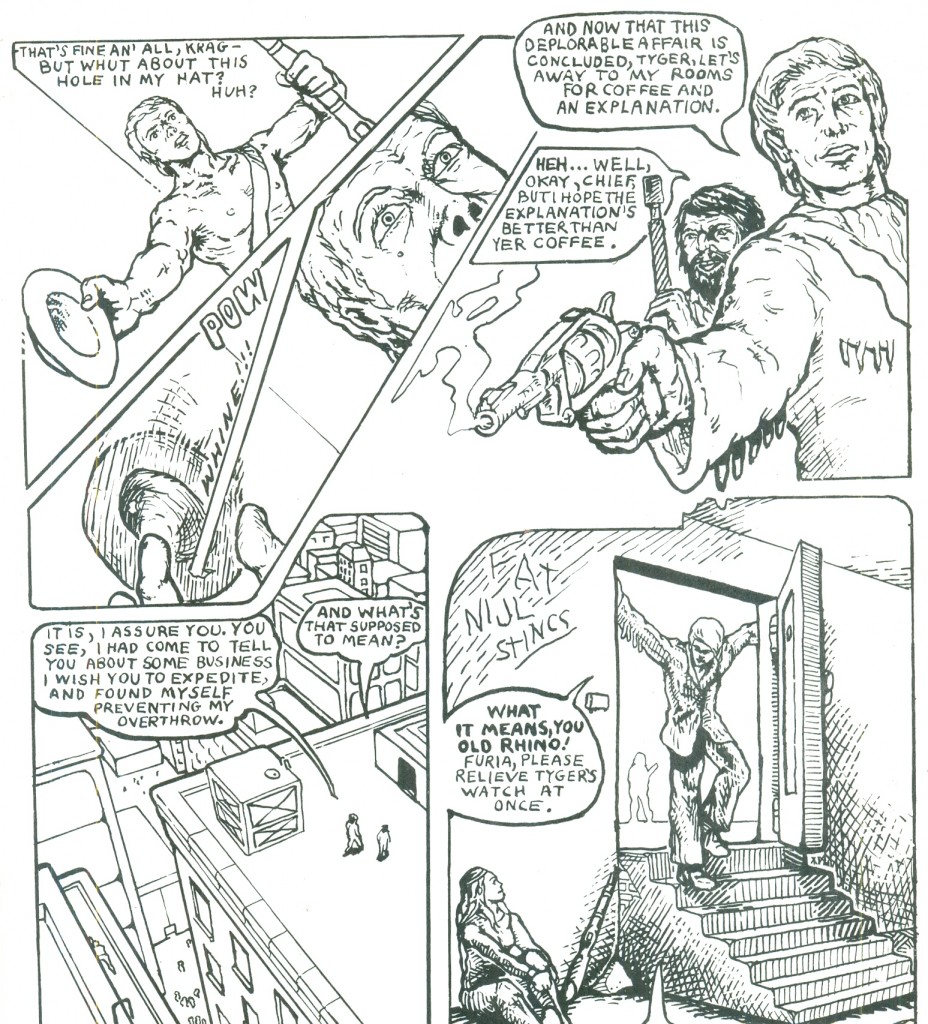

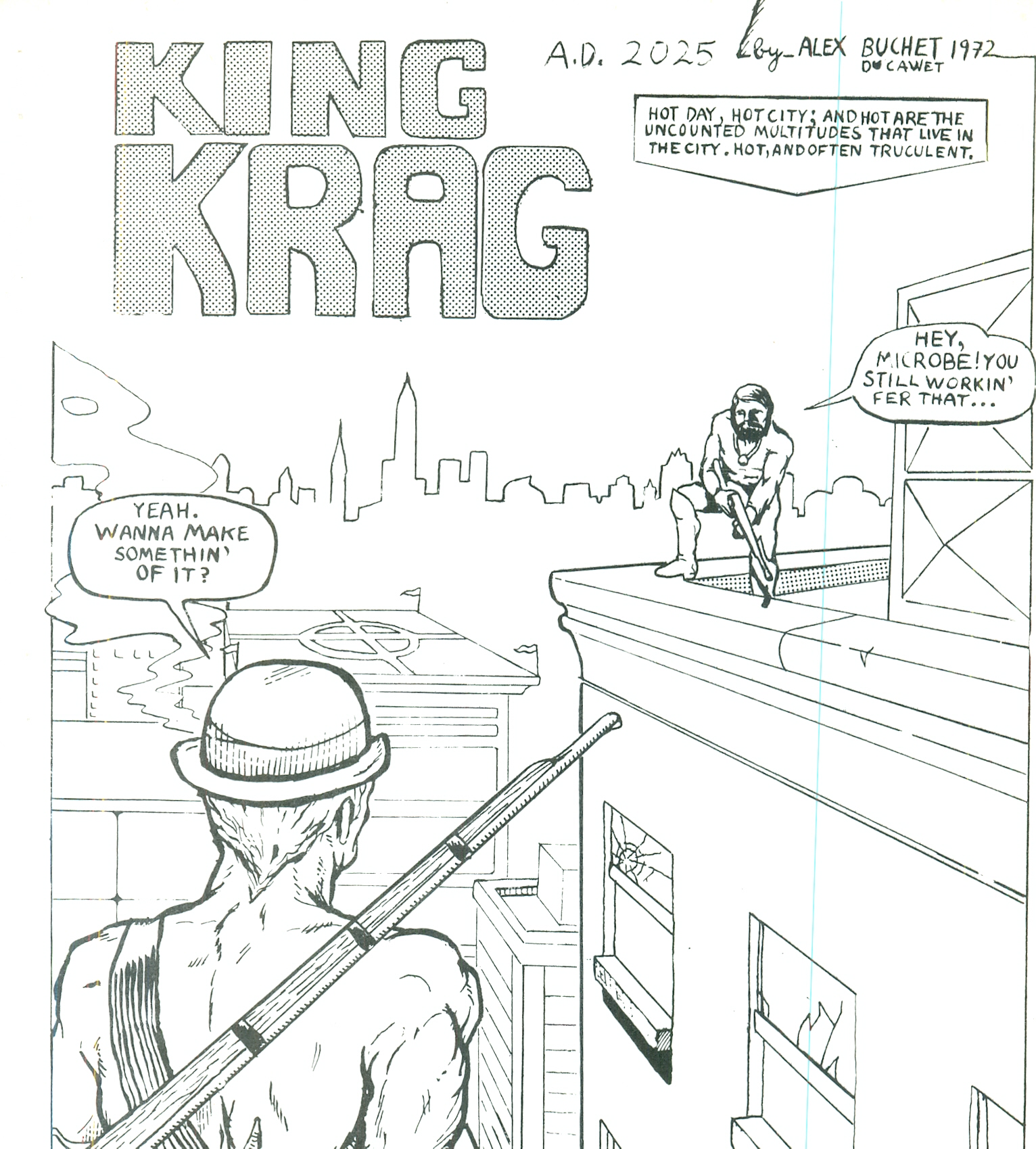

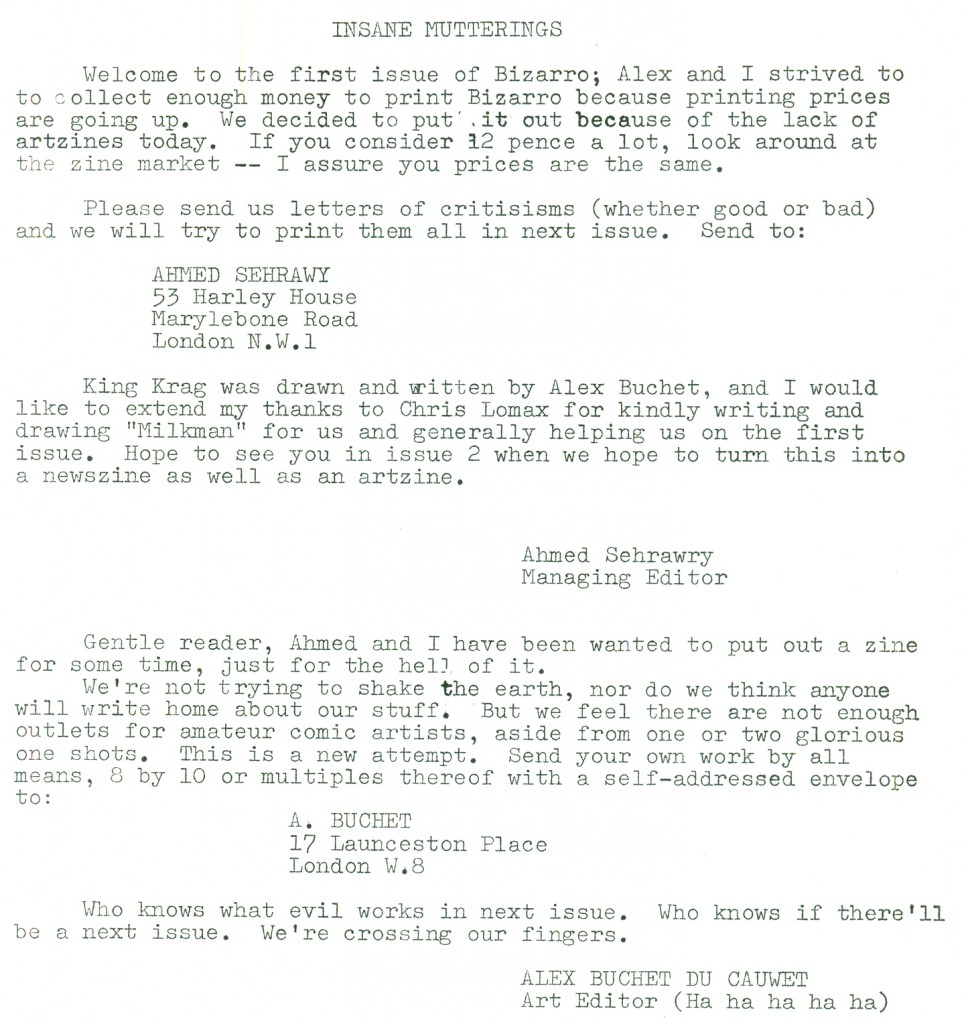

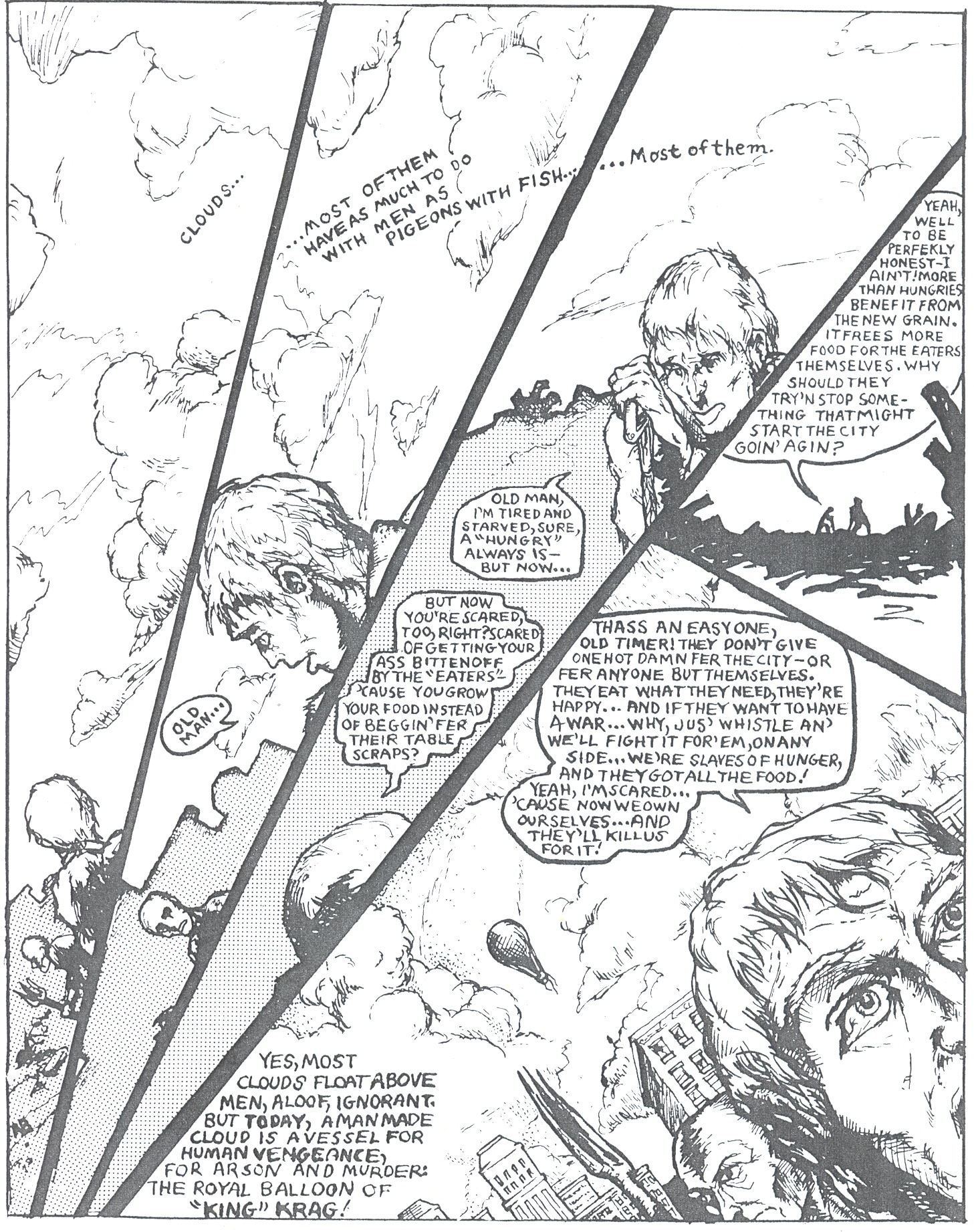

And indeed that was my thinking when, aged sixteen, I started drawing a comic strip with the alliterative title ‘King Krag.’

Now, printing options were fairly limited in those days. Mimeograph was still widespread; photocopies were becoming available, but they couldn’t reproduce solid blacks and needed a special paper. Offset printing was expensive.

This last limitation, though, was swept away by a new business model. The Instantprint chain offered printing in small runs at a reasonable price. Not free, though, and I struggled to get together the twenty-five pounds needed for a print run of 200 fifteen-page pamphlets.

I took a decision that I regretted deeply at the time: I sold most of my comics collection.

In retrospect, I’m very glad I did. It broke the anally-retentive hold collecting had on me: thenceforth I would buy to read only. I would no longer obsess about completing runs of series and throw away money on stuff I didn’t even like to close gaps in my collection.

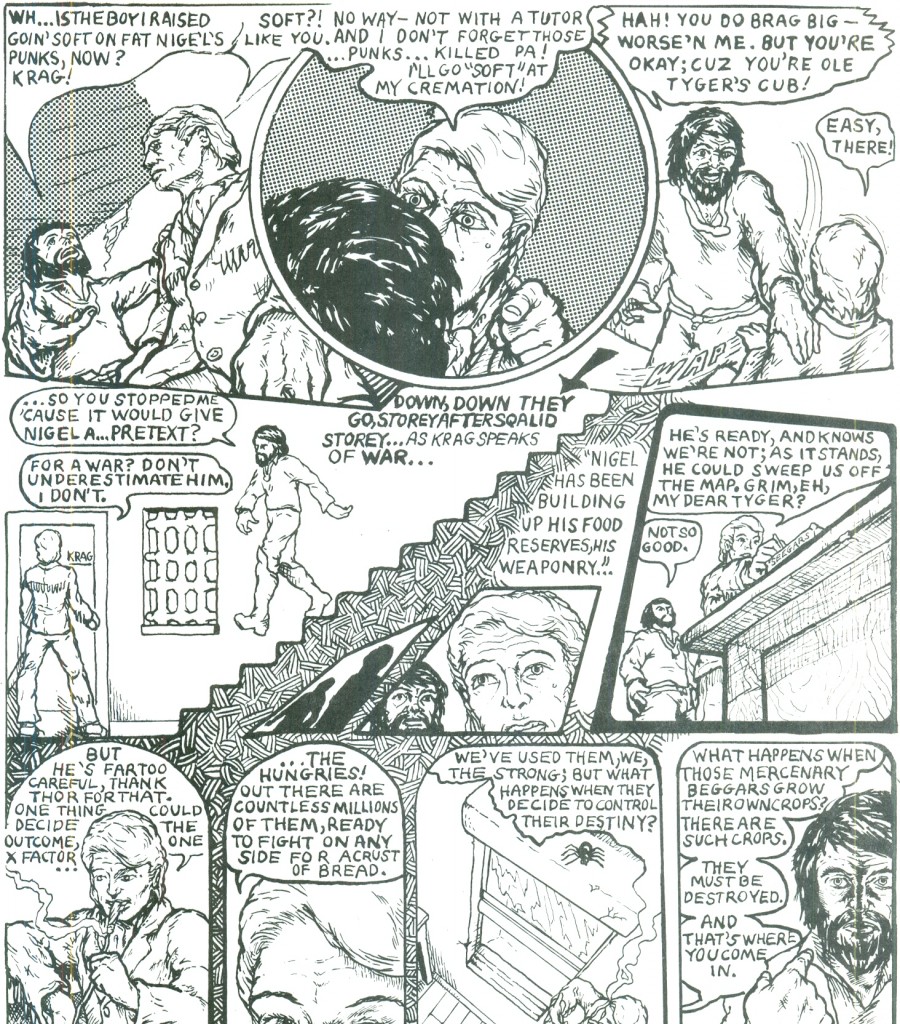

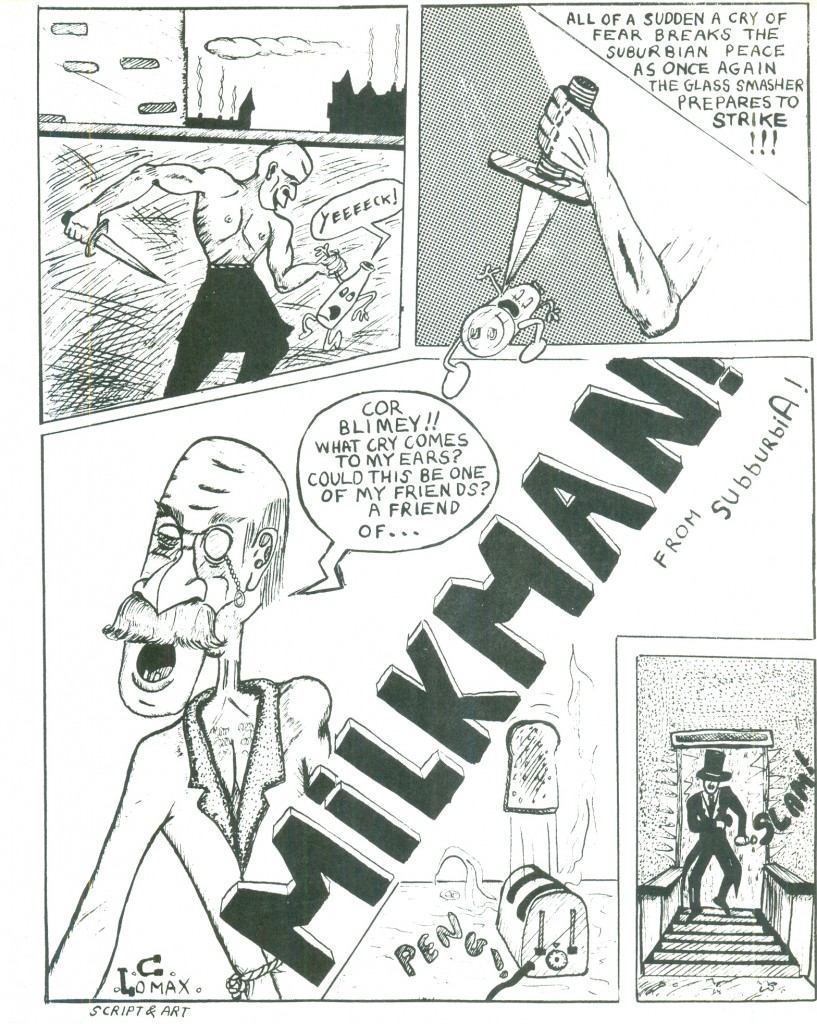

I teamed up with my friend Ahmed Sehrawry, who took the impressive title of Managing Editor; really, I just wanted someone to talk to– I did all the actual work. Another friend, Chris Lomax, provided the strange back-up strip ‘Milkman.’

I drew the strip same-sized (A5). Never again. You don’t save any time. In fact, the six pages took me over a year to finish.

I remember bringing the package of printed pages back to my school — the French Lycée in London — to the art department, where my art teacher gave me a room and a bunch of tables: yes, we were collating and stapling by hand– we couldn’t afford machine collation or binding. No worries, my friends and I had a good time; a collation party is much like a corn-shucking bee, an undemanding communal activity, interrupted by the odd tea break.

(Tea is one addiction I picked up in England.)

By God, the first time you see your work in mass reproduction is a trip and a half! And the first copy of a finished work…does that feel good in your hands.

I was seventeen and a publisher.

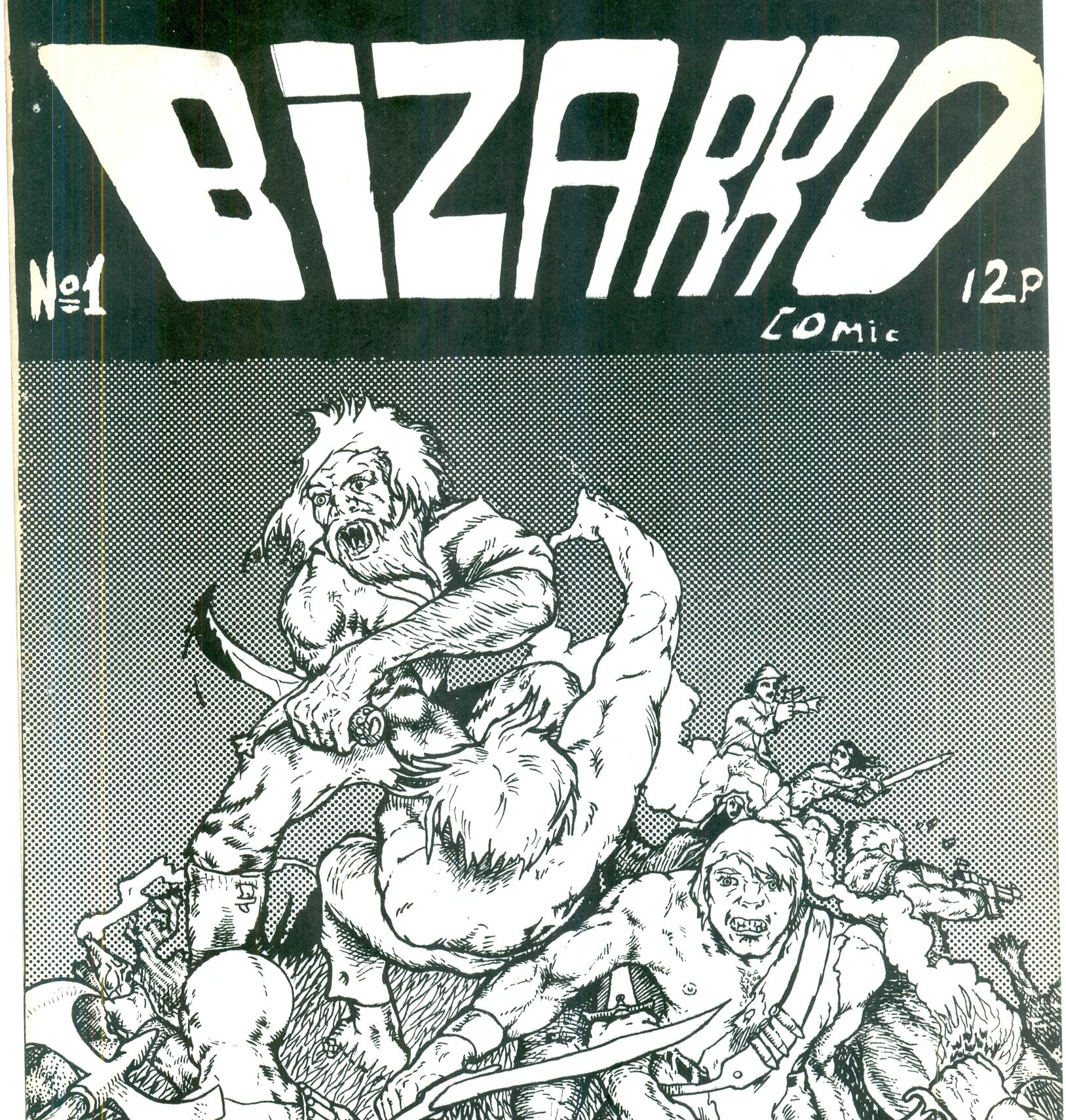

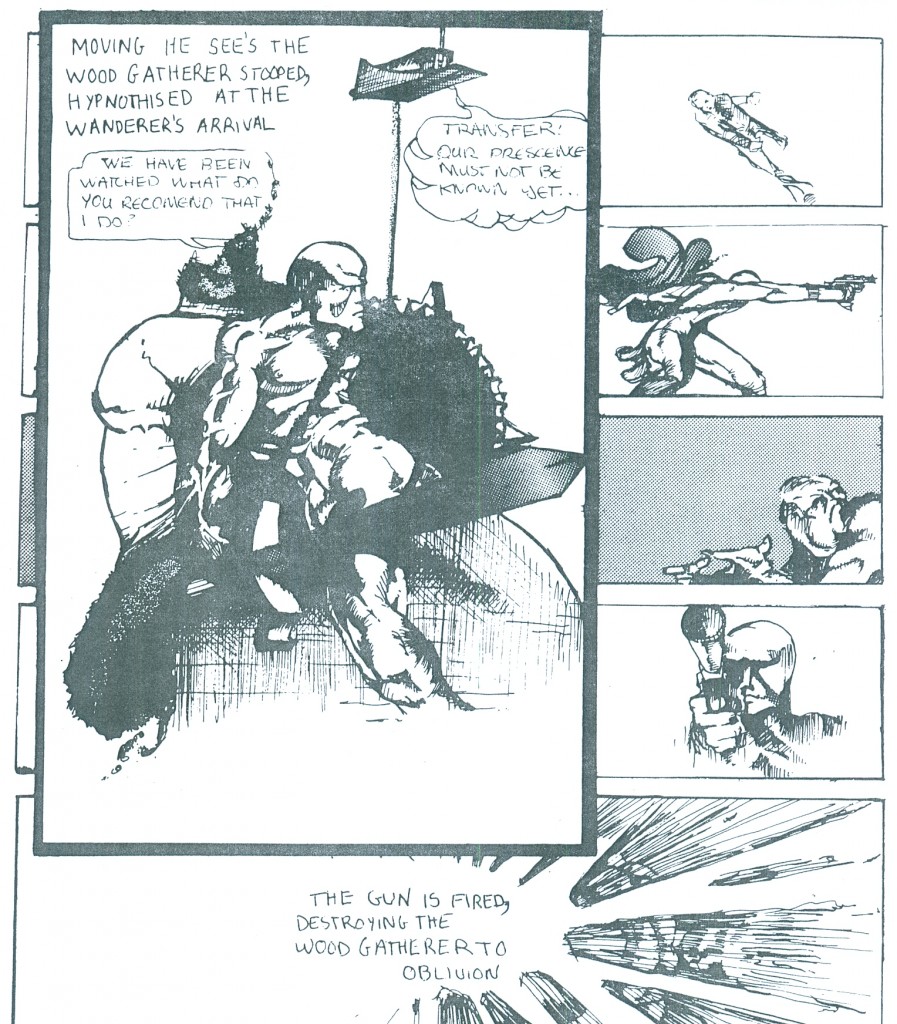

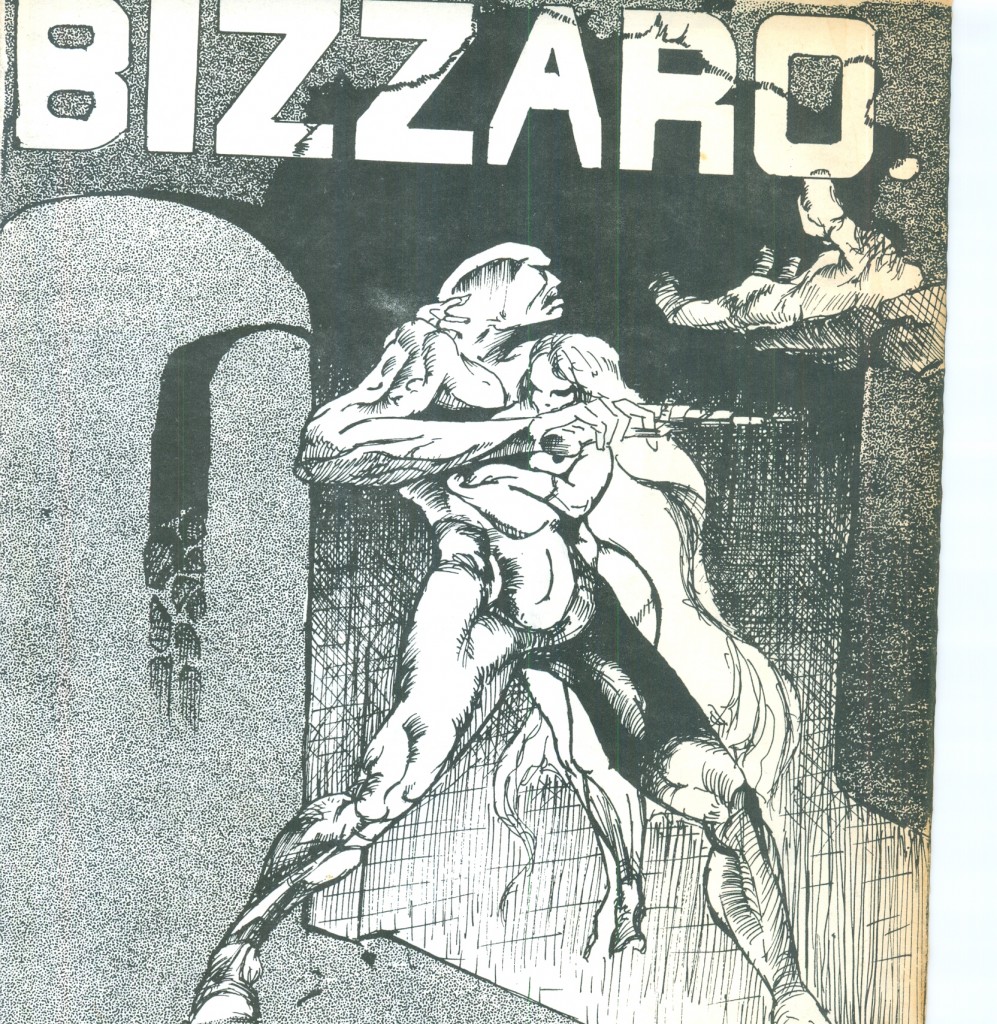

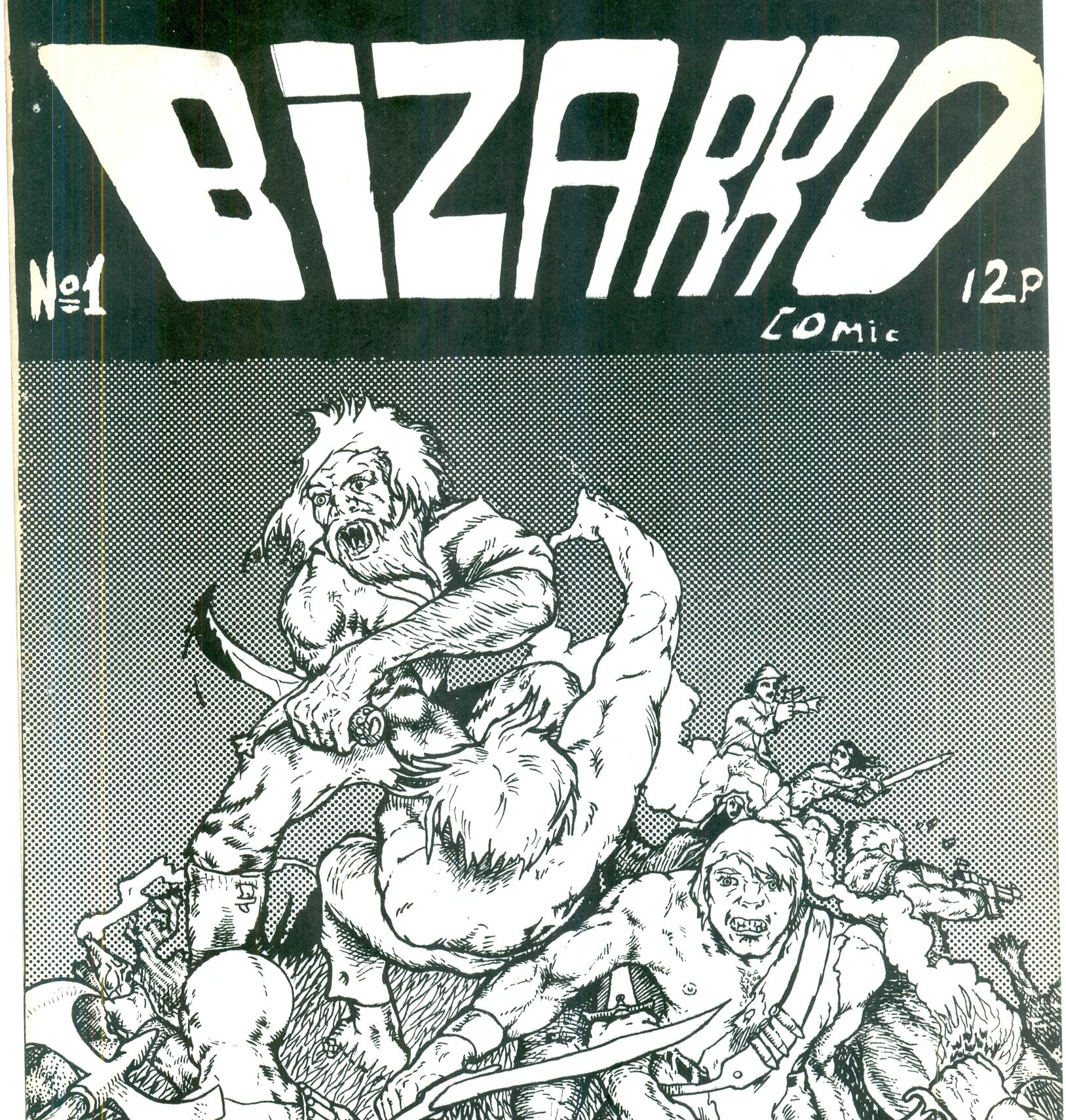

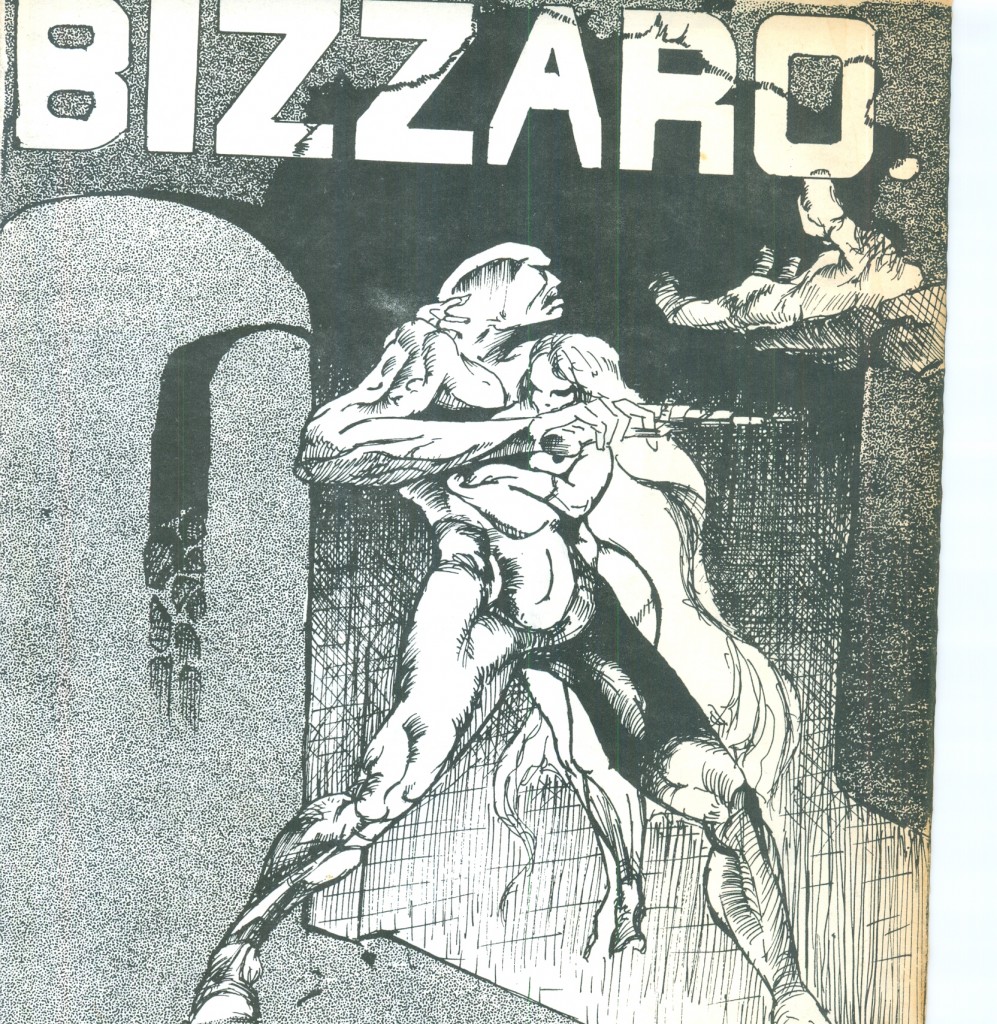

Now, I will beg your indulgence for the artwork shown. It was produced by an immature young fellow who wore his influences all too prominently; I’m harder on that boy than you could ever be. Still, as an artifact of a past 38 years gone, it repays arm-length study. Here is the cover of Bizarro #1:

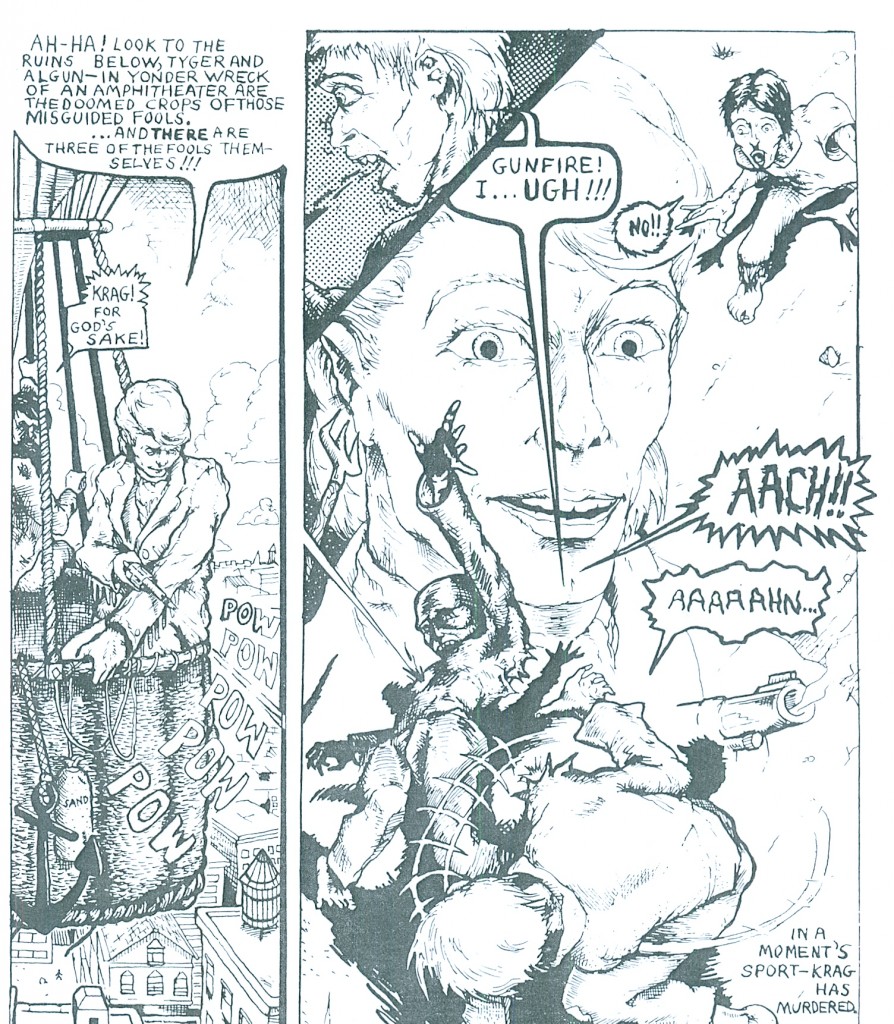

What strikes the 55-year-old me about the seventeen-year-old me’s drawing above is the level of violence. True, the culture was moving that way; this was the age of films like The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange. But looking at that cover, I can only ask in dismay: was I that full of incoherent rage? More than another typical teenager? Apparently, yes.

Influences are embarrassingly obvious: Frank Frazetta, Barry Smith. A less obvious influence is Géricault‘s Le Radeau de la Méduse:

…which explains why so many of the figures therein rudely turn their back on the reader.

Also irritating are the visual tics picked up from Berni Wrightson: the ‘saliva ropes’ in the shouting character’s mouth, the ‘twisty hair’ on his forearms.

Note the patterned background: I had just discovered Letratone, and like so many neophytes was inclined to abuse it, as the luckless readers of this blog shall soon confirm.

On the plus side, the composition holds together fairly well (you can’t go far wrong with triangles) and there’s a real sense of depth.

But that sloppy logo is unforgiveable.

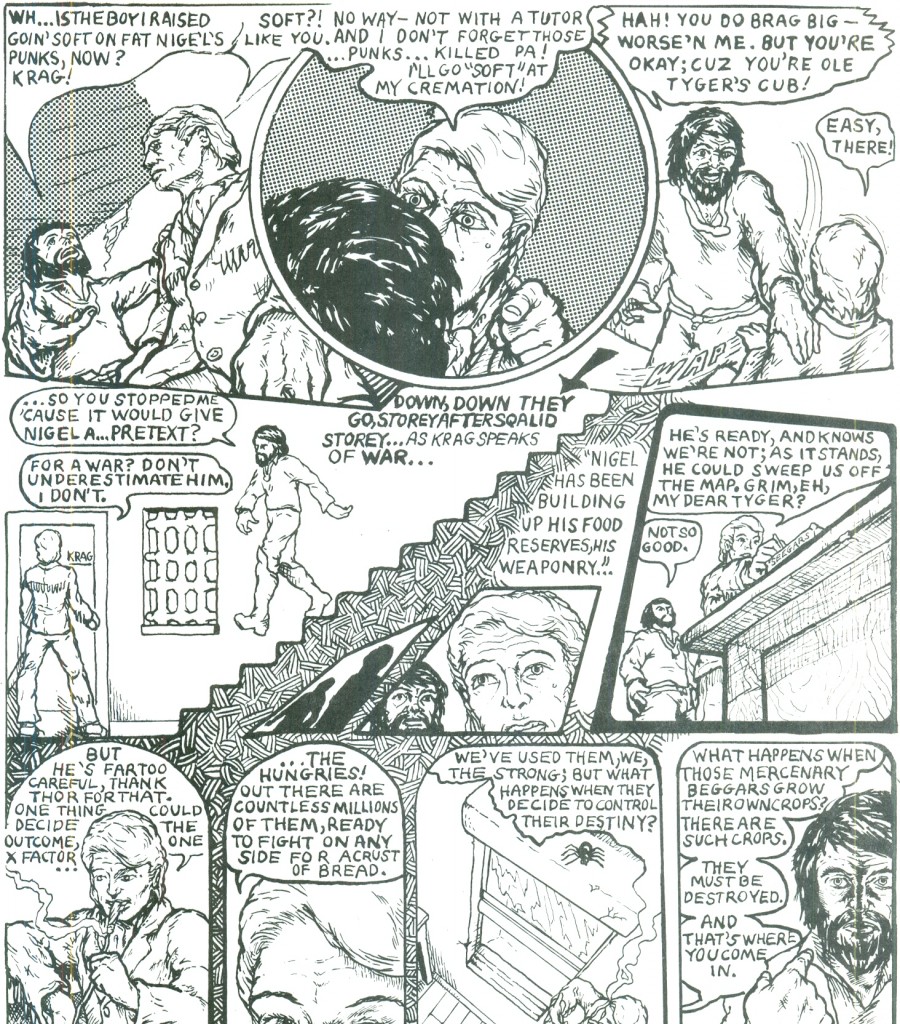

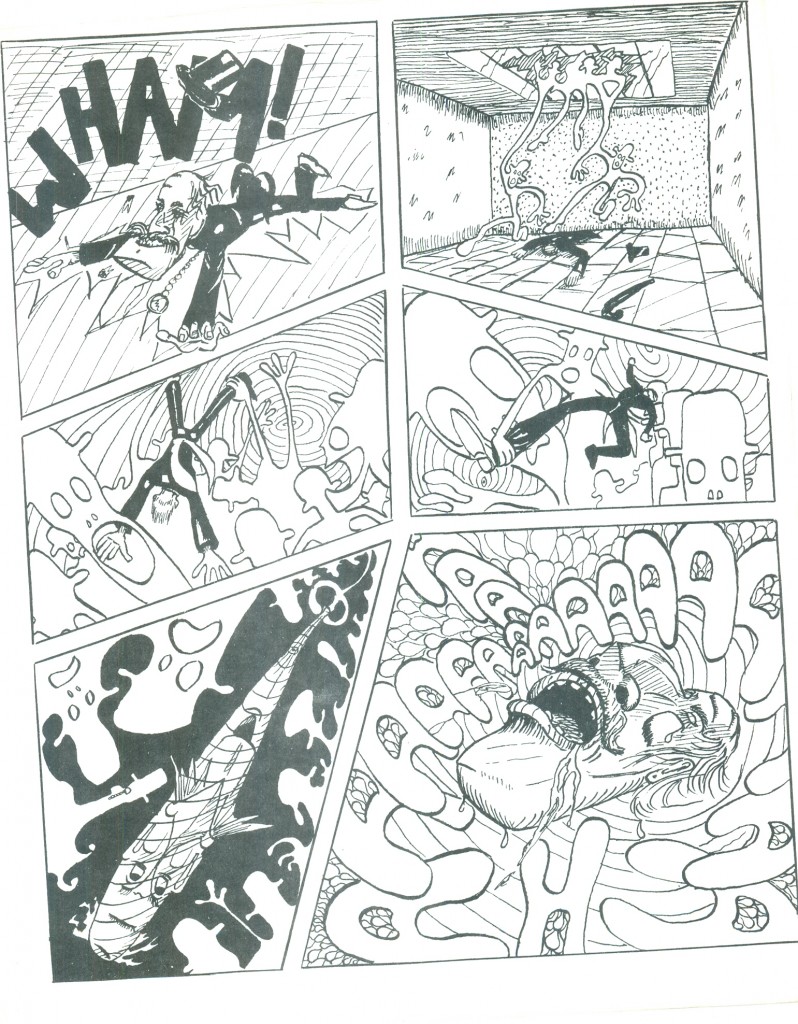

On to the strip. It’s a nightmare of incompetence.

Note on this splash page how I avoided heavy blacks: at that time, I was intending to produce this via photocopy.

Apparently, in the year 2025, for some reason they revived flintlock muskets…

It’s the standard post-apocalyptic fun future, inspired by Roger Zelazney‘s novel Damnation Alley and, oddly, Jack Kirby’s early Jimmy Olson comics. A bit over-tidy for after the apocalypse

I’m surprised to see how competent the perspective is: I don’t recall having studied perspective at that age (16), but I guess I had.

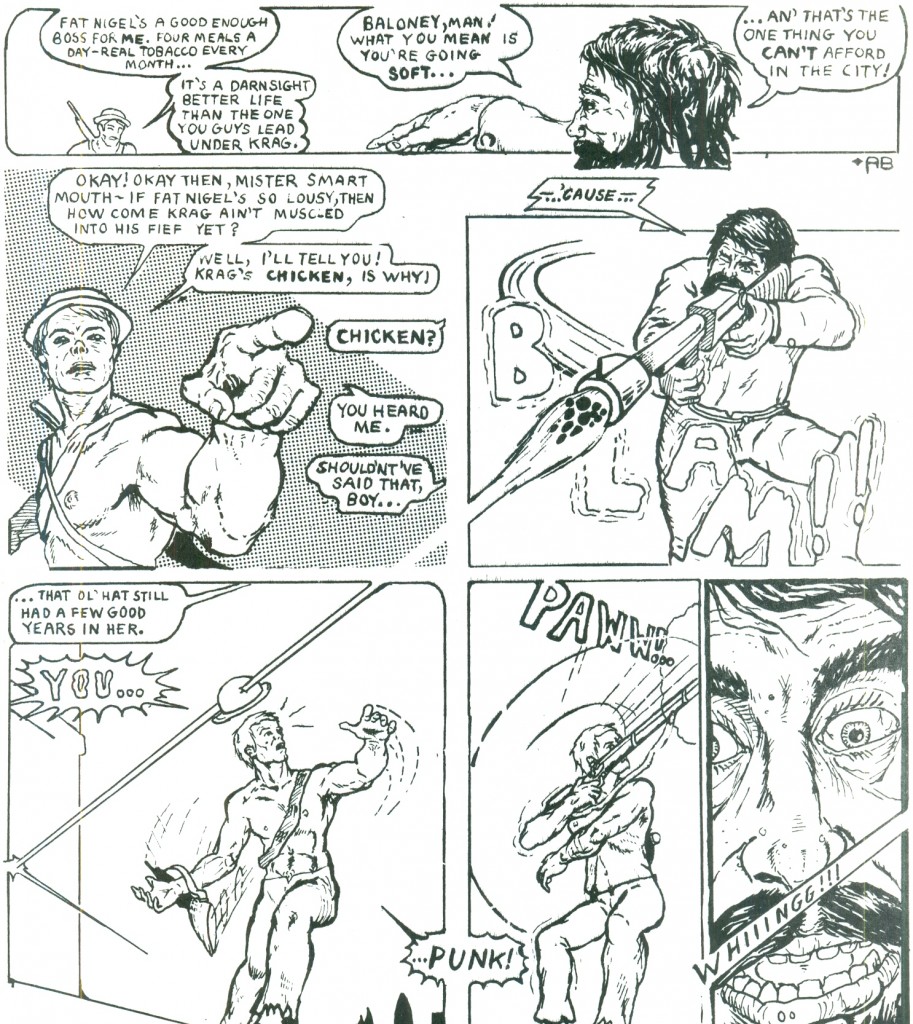

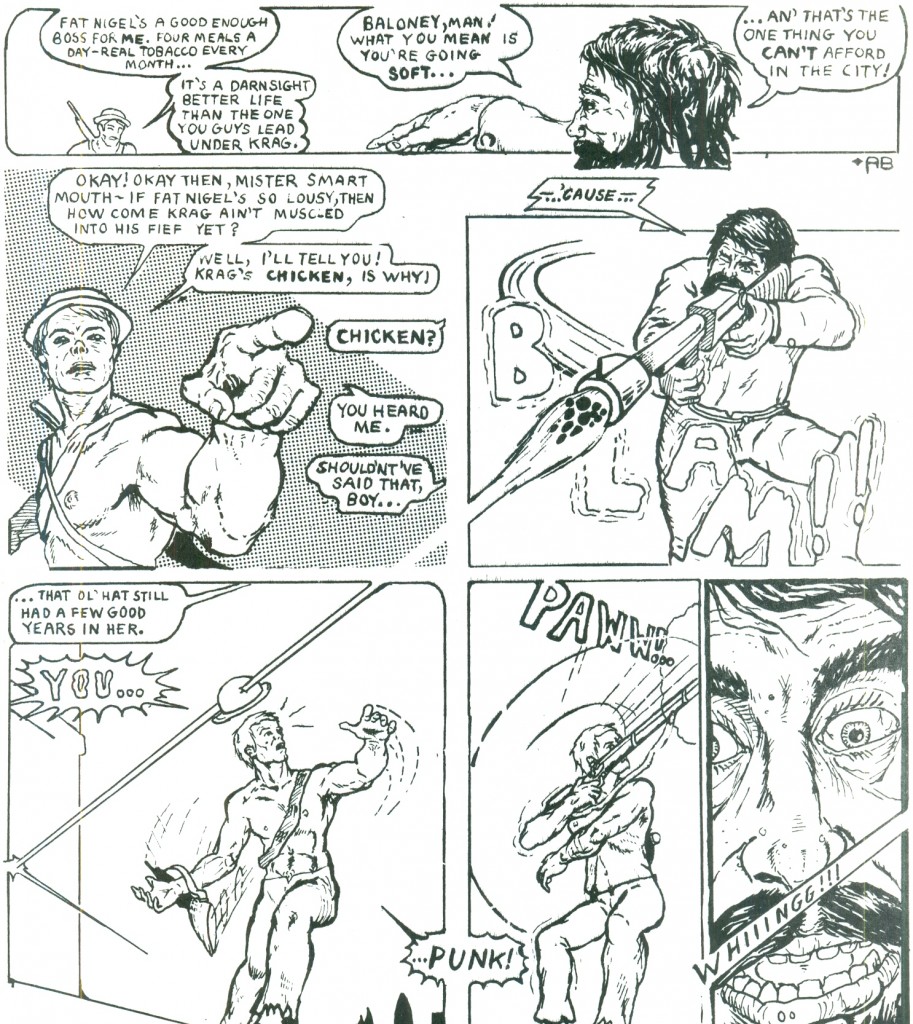

I’m afraid lousy dialogue and worse lettering are the hallmarks of my writing here. I was a nice white middle-class boy, so of course I tried to talk tough. Guns are by definition cool at that age.

Not the fishbowl-lens perspective on the guy’s hand in panel two. I was probably imitating Neal Adams.

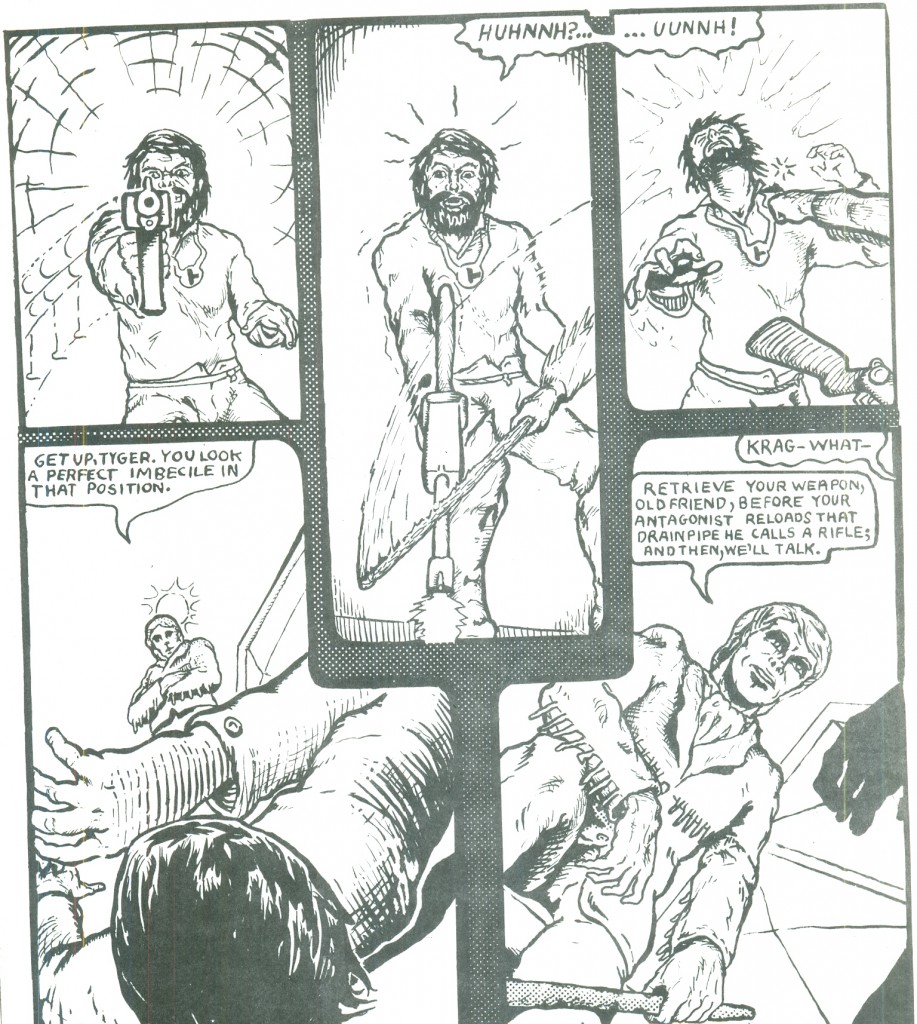

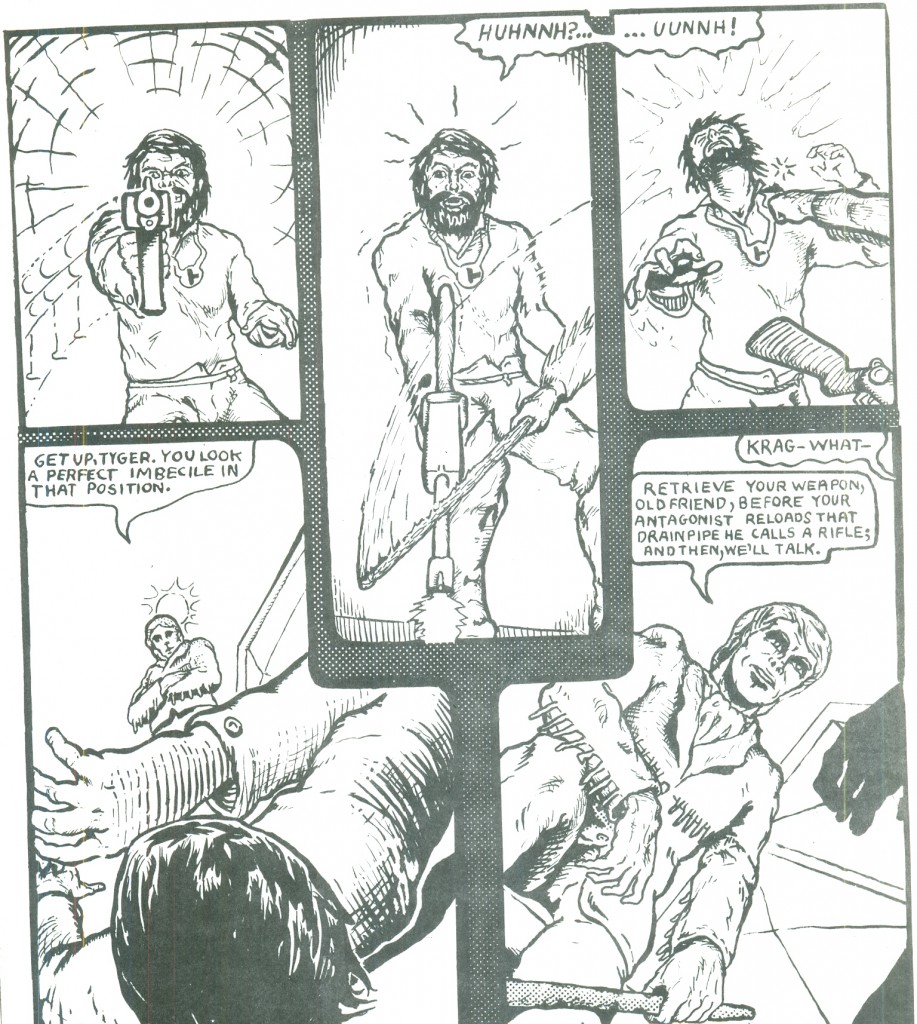

The fussy, unnecessarily confusing odd panel shape was a disease of the time. I guess I was following in the footsteps of Jim Steranko and of Neal Adams. Note the last panel: you won’t see another woman in this macho world for macho men.

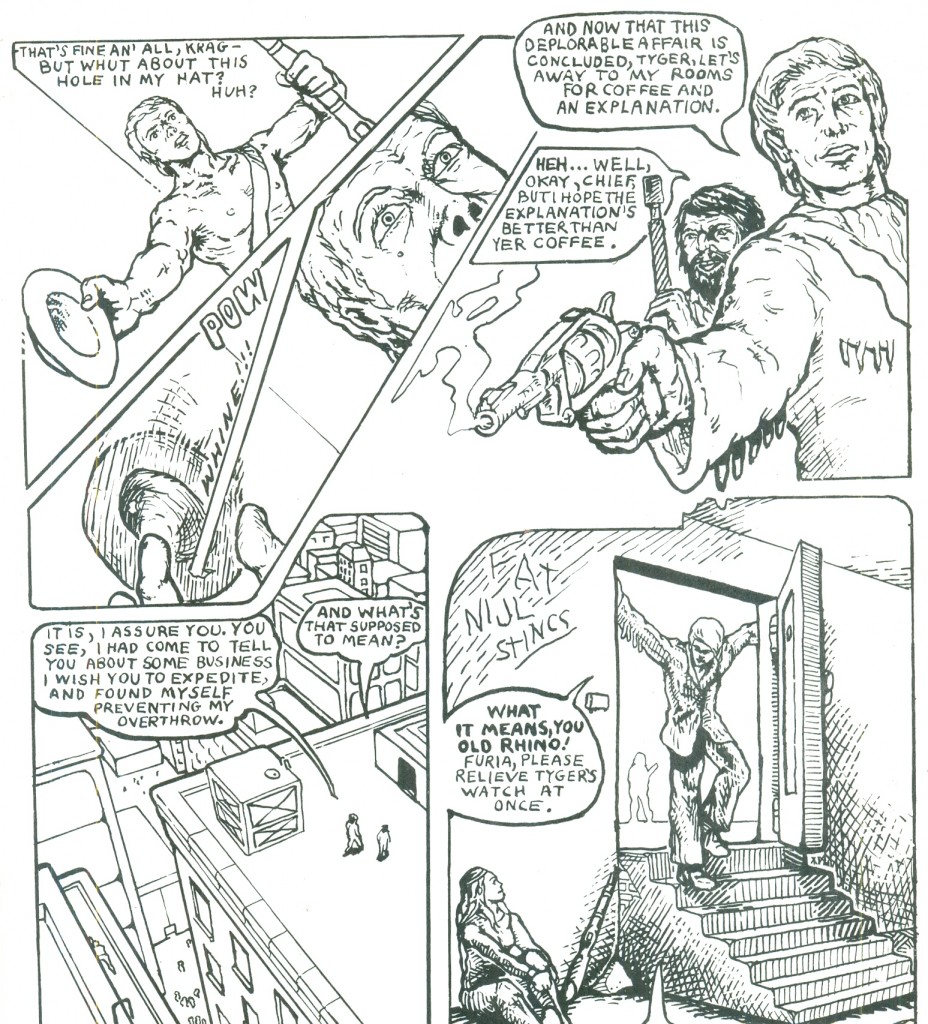

More weird layouts, odd angles, arbitrary cropping. The guy walking downstairs looks like he’s about to fall on his hairy face. I learnt that the real challenge in drawing isn’t in detailing giant space armadas– it’s in showing someone walking downstairs or opening a door.

So endeth chapter one.

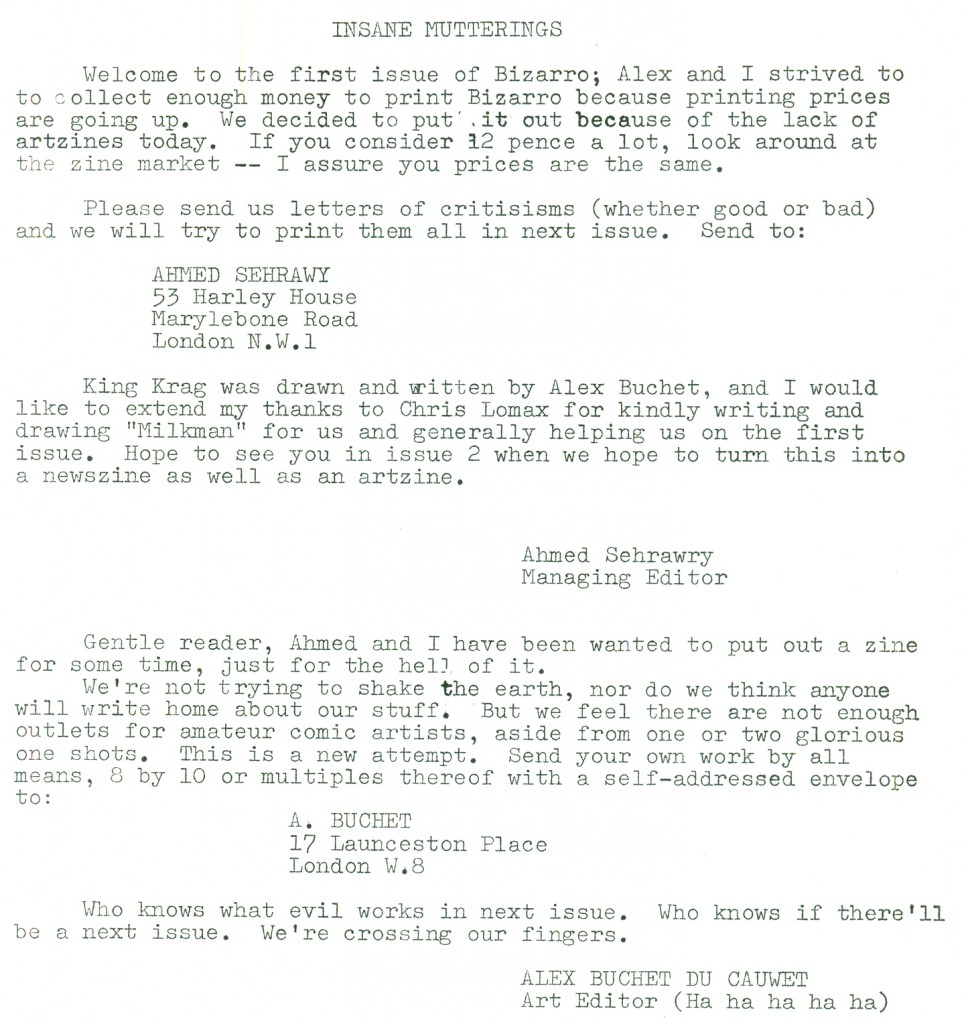

There followed a mimeographed page of messages from the editor. I’m relieved to note that neither Ahmed nor I took himself very seriously. It was typewritten: word processors didn’t exist, and typesetting was expensive.

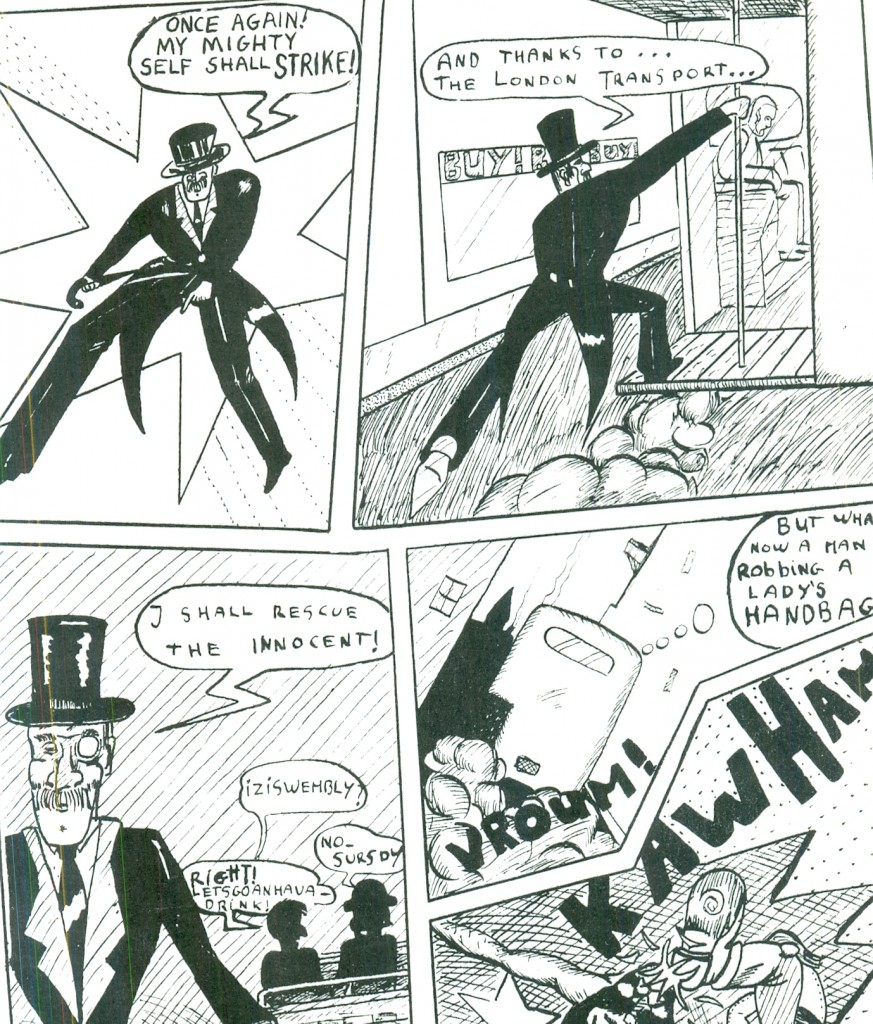

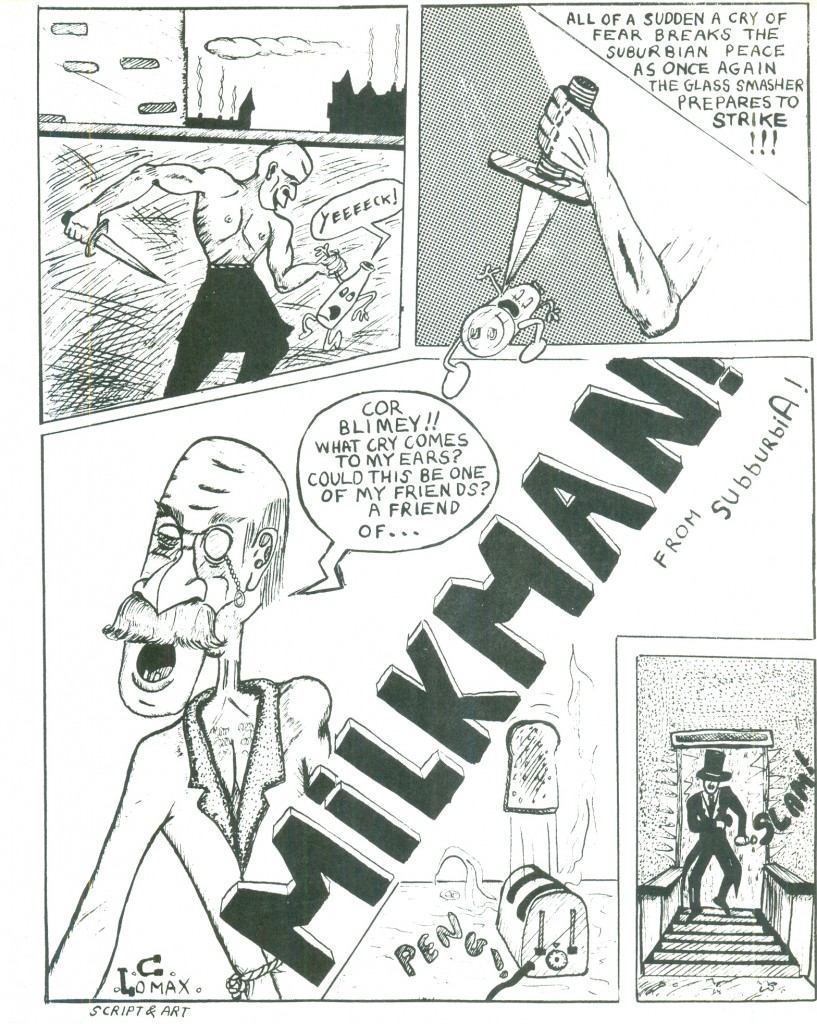

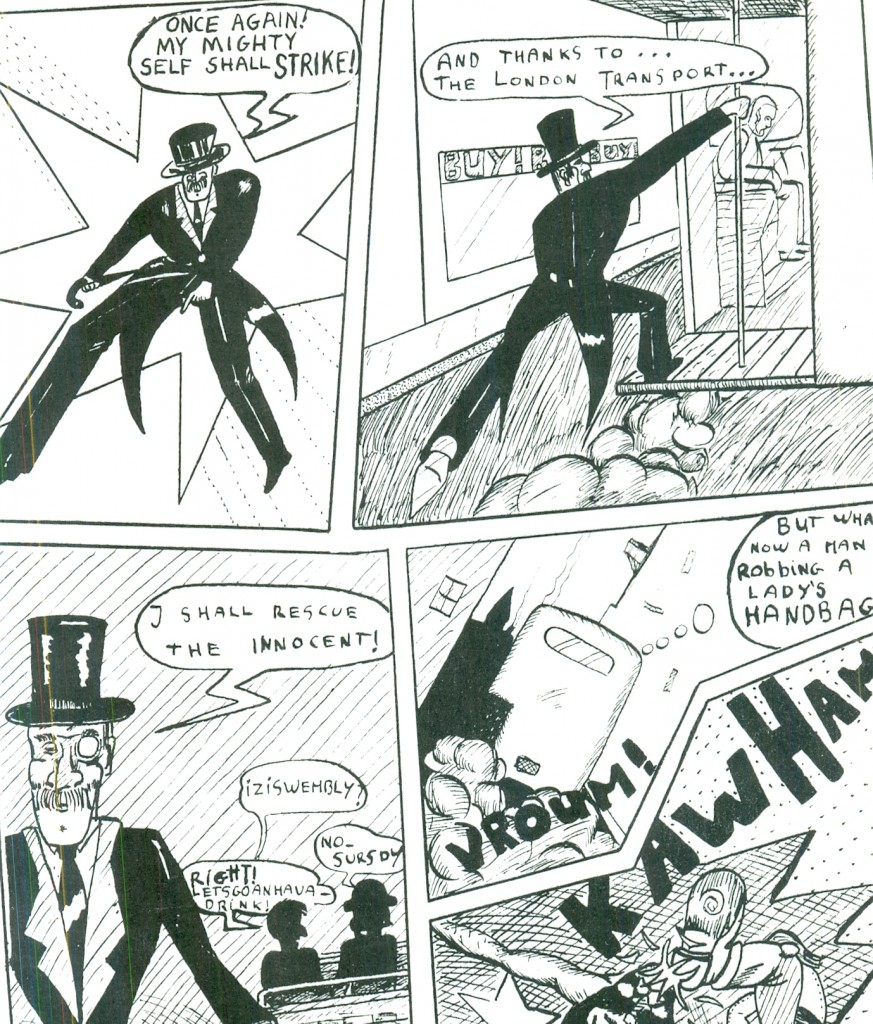

Rounding out the book was Chris Lomax’s ‘Milkman’. Its primitivism and absurdity have stood the test of time better than my overblown strip. Chris went on to be a successful stage and set designer in Paris, working on films such as Betty Blue.

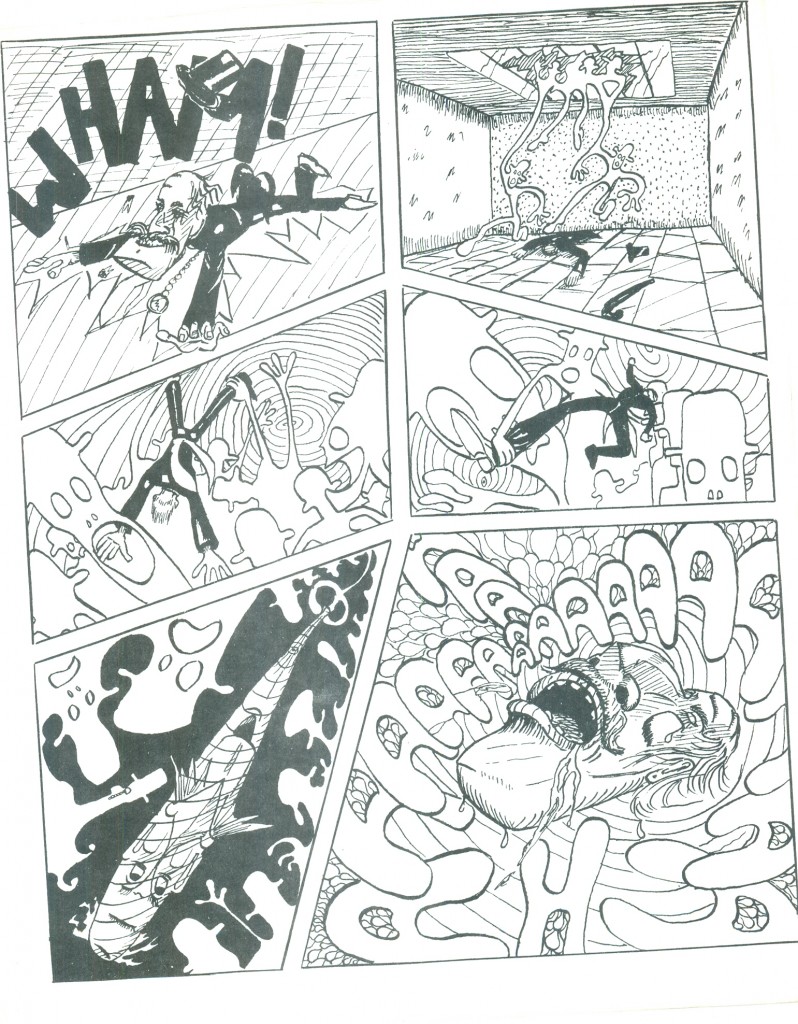

We return to the horrors of mimeograph. Bram at ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ let us drop off some copies on consignment if we’d run a free ad for his shop.

Well, Bram, you get what you pay for. And this is what ‘free’ pays for:

Ahmed took fifty copies to sell at his school; I took the remaining hundred and fifty to sell in mine. I recruited my brothers Philippe and Gérard, as well as friends like fellow comics- fan Sanjit, to spread out through the school and tout my inky baby.

We sold out within 24 hours.

It seems that publishing a comic in high school is like giving a rock concert in the gym or acting in the school play. The kids’ll support you just because you’re one of them. (Our principal was something of an arsehole about it, as I hadn’t asked for his permission; fuggim, I was out of there anyway.)

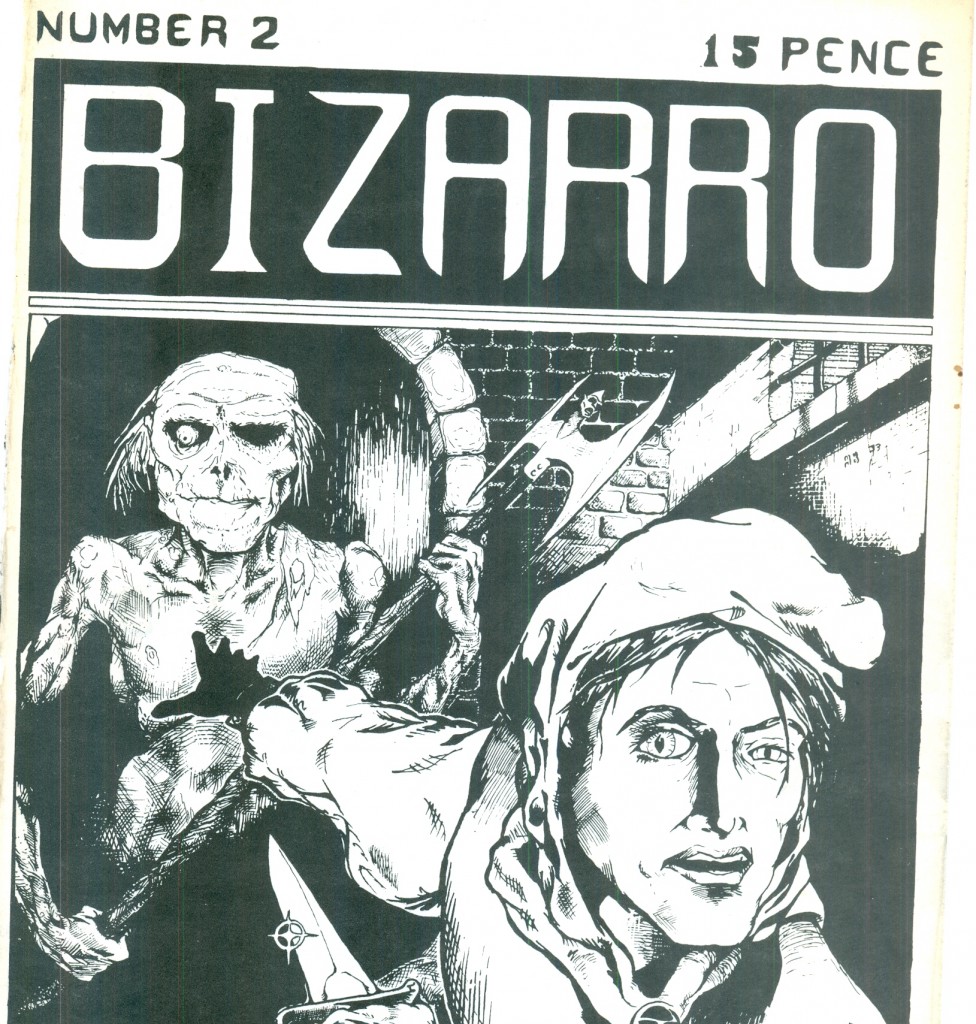

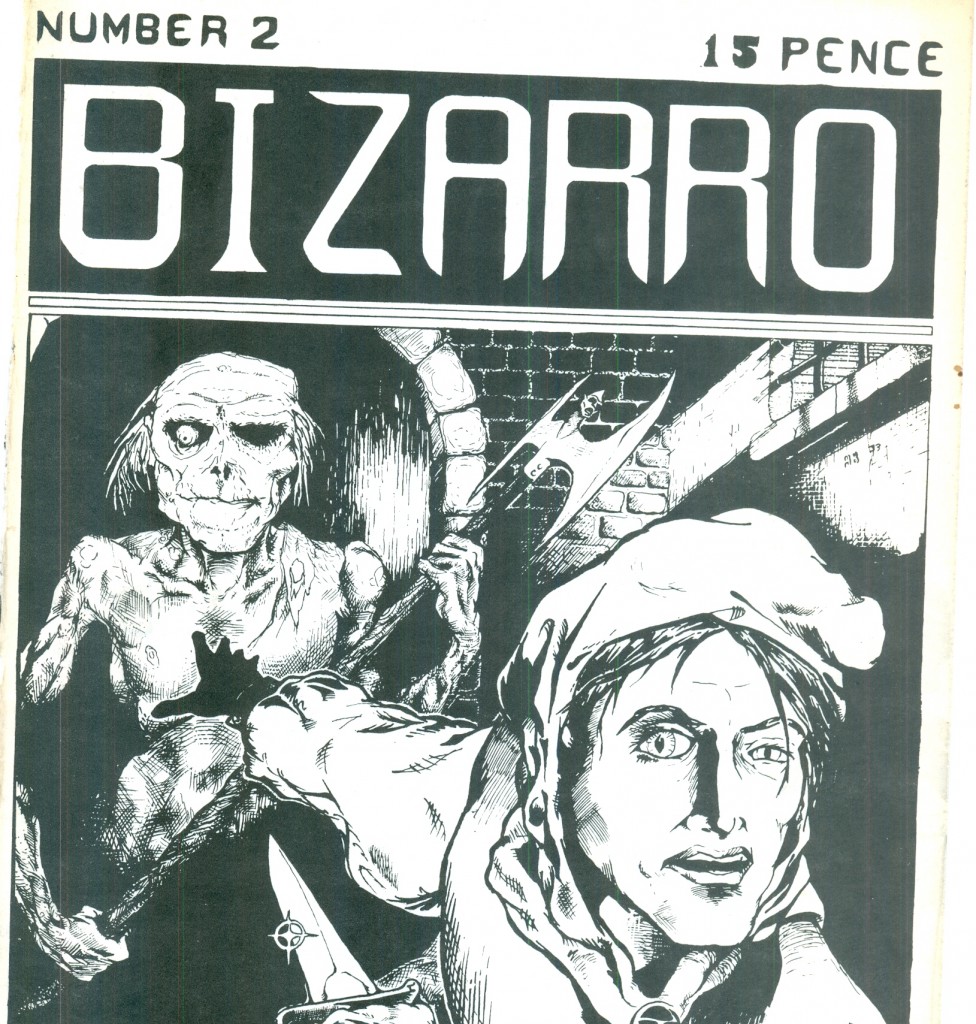

Issue 2 came out over a year and a half later. Now I’m a terribly slow artist, but this was ridiculous.

I had gone to Paris to study art at the Faculté des Arts Plastiques et des Sciences de l’Art of the Sorbonne. I was studying electro-acoustic music under Yannis Xenakis, screenwriting under Eric Rohmer, conceptual art under Journiac, comics under Jean-Claude Mézières.

I had outgrown my adolescent strip. It frankly embarrassed me.

Why didn’t I just give it up, then? A misplaced puritanism– I had vowed to break my bad habit of starting projects and not ending them; and I didn’t want to let Ahmed down.

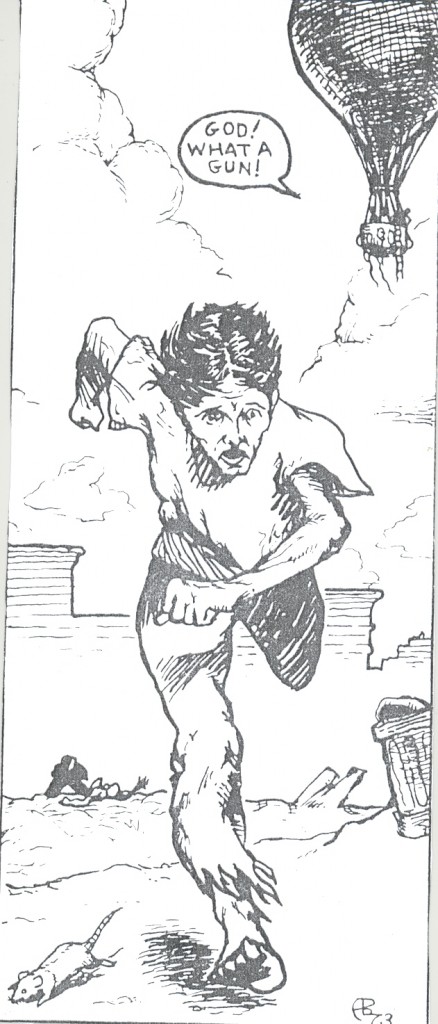

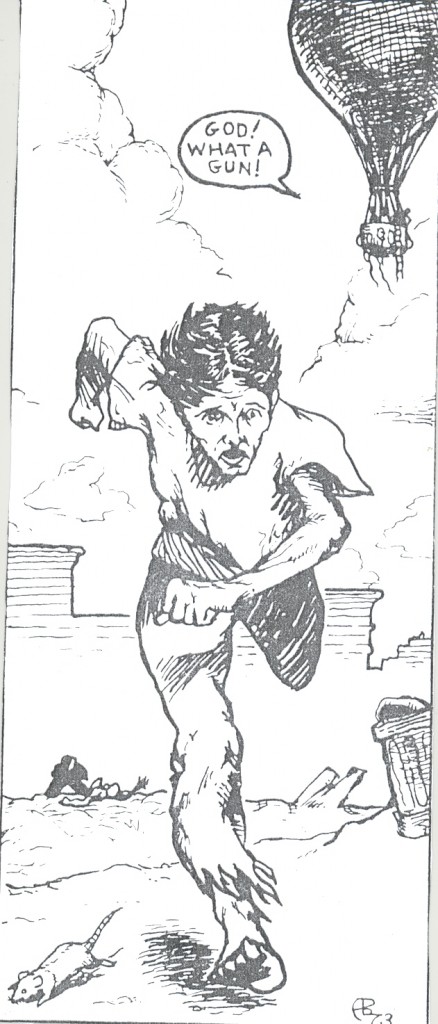

The second issue boasted another odd cover, replete with clichés taken from Frazetta, Ploog, and Gustave Doré. I like the poor sap in the foreground’s expression. “I gotta turn around…but I really don’t wanna turn around…but I gotta…”:

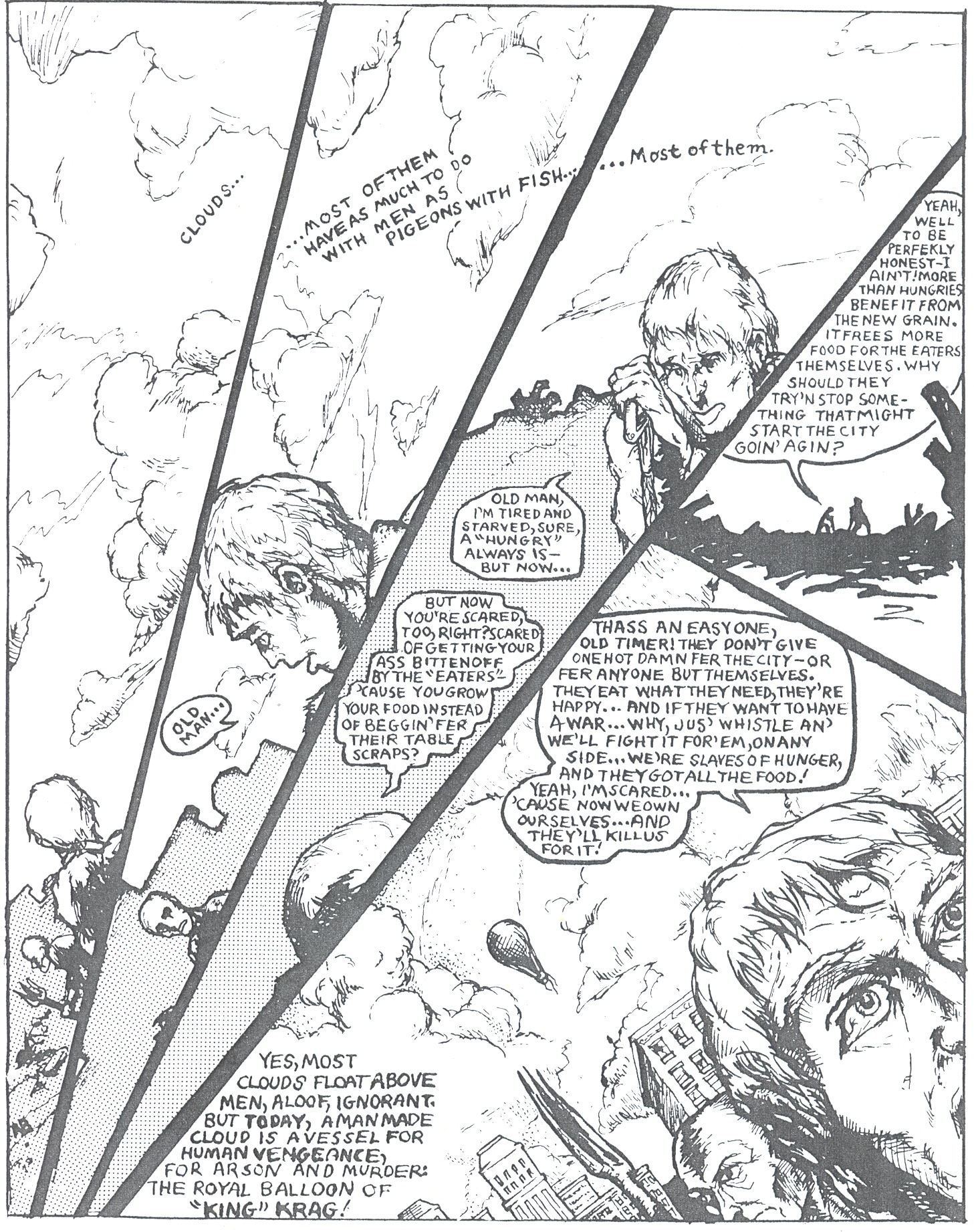

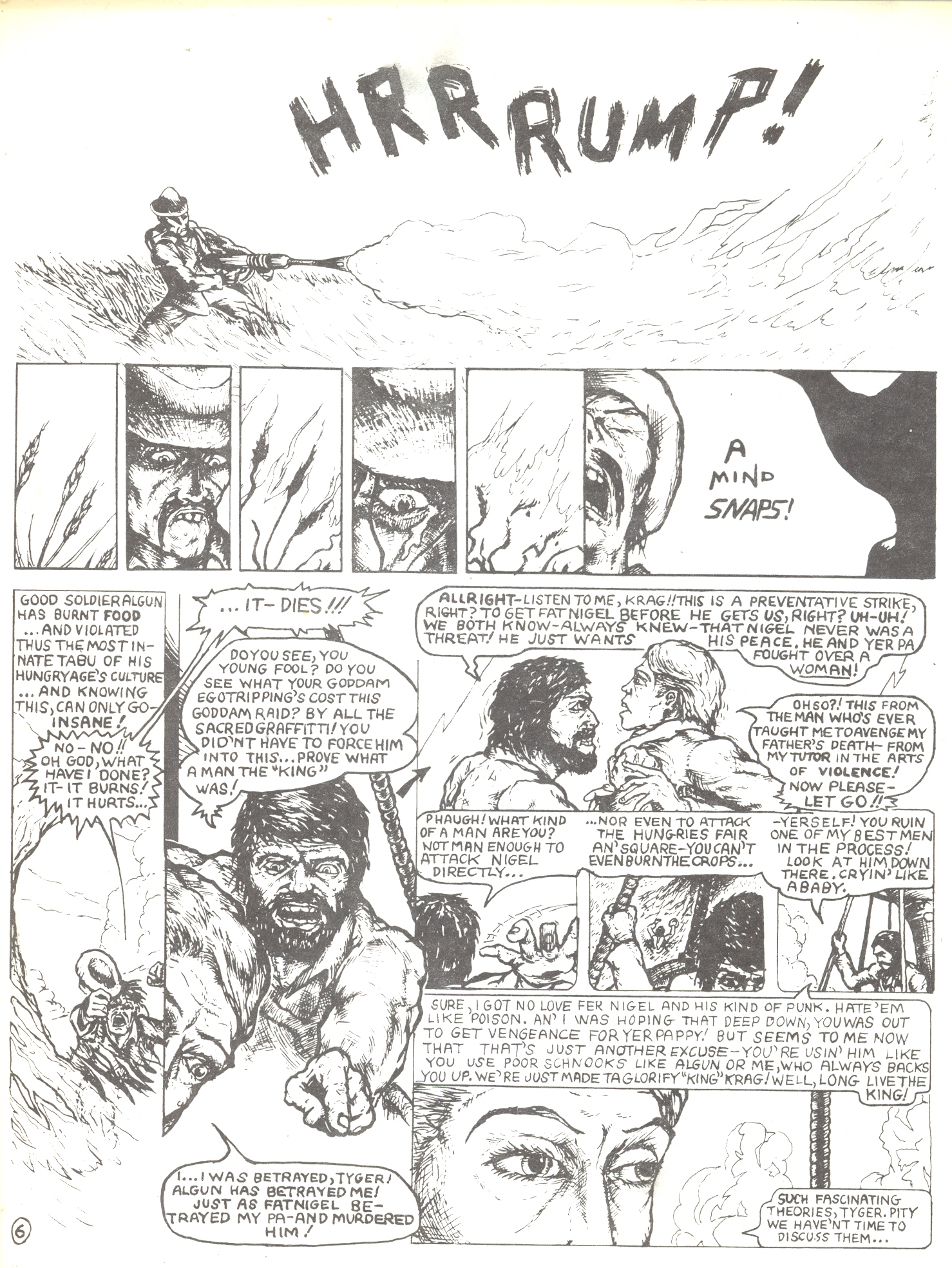

Page one– more arbitrary panel noodling, fatuous captions, and peasants dutifully giving us an “infodump”: a massive exposition of stuff they already know and shouldn’t be repeating.

God, the inflation of those speech balloons.

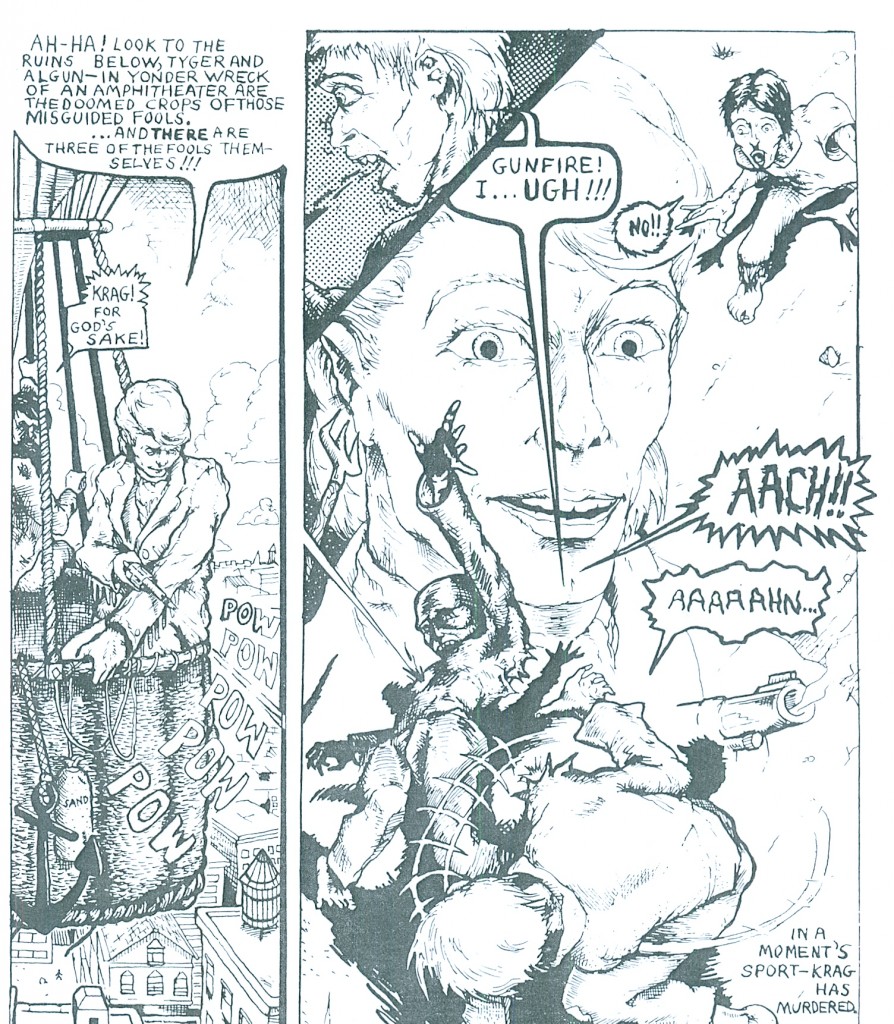

More gratuitous violence follows. (I give myself some credit for actually researching hot-air balloons.)

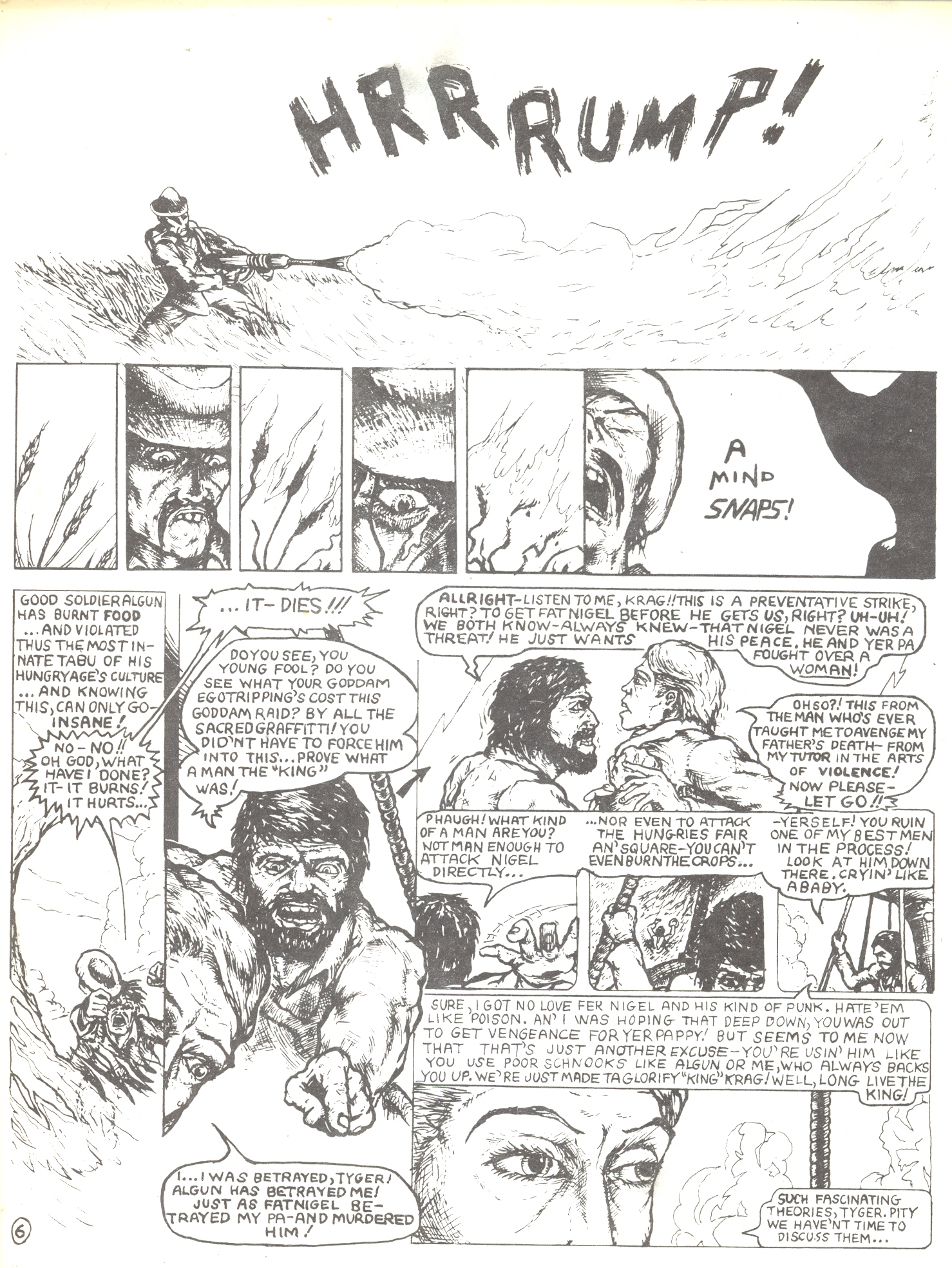

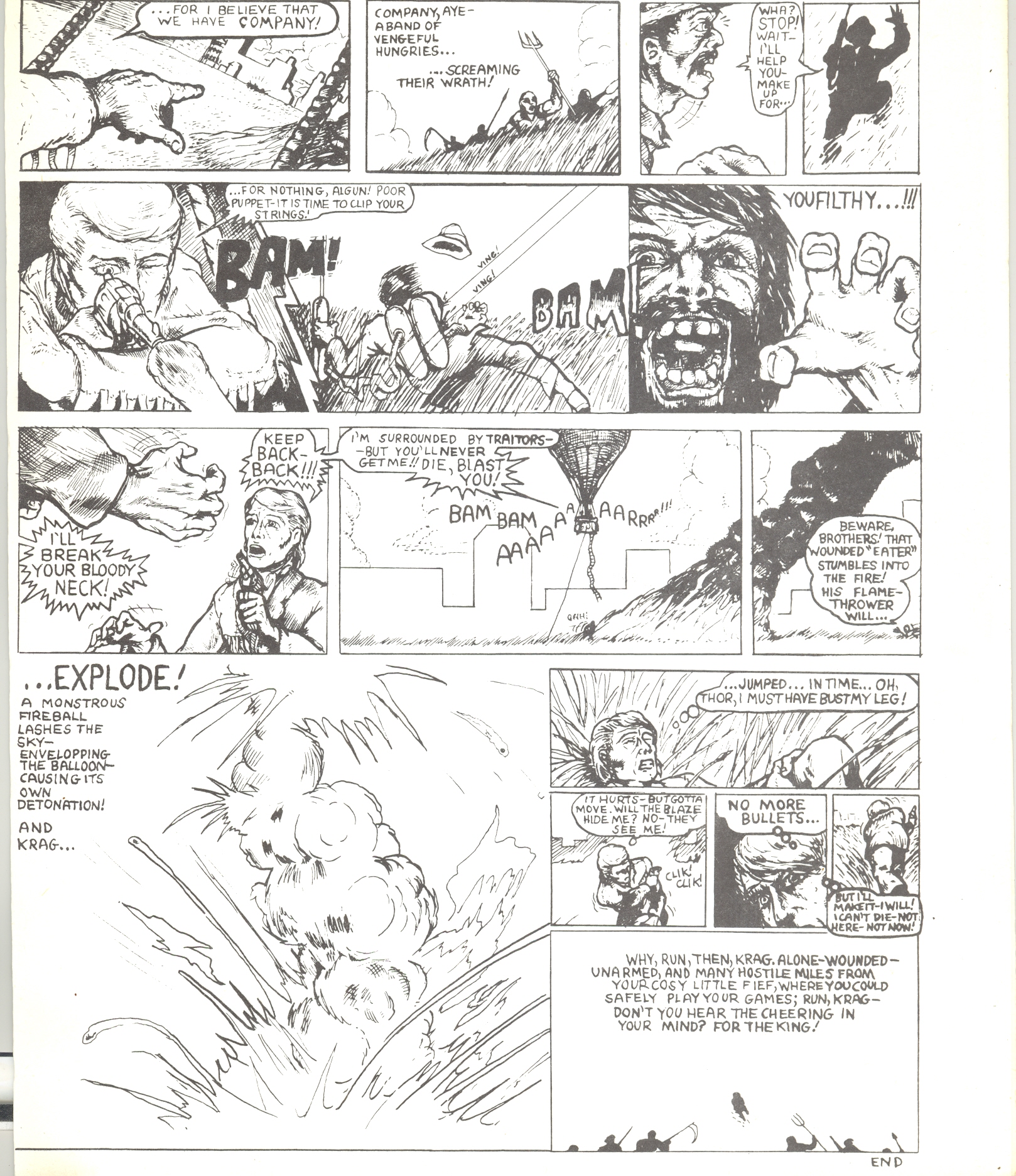

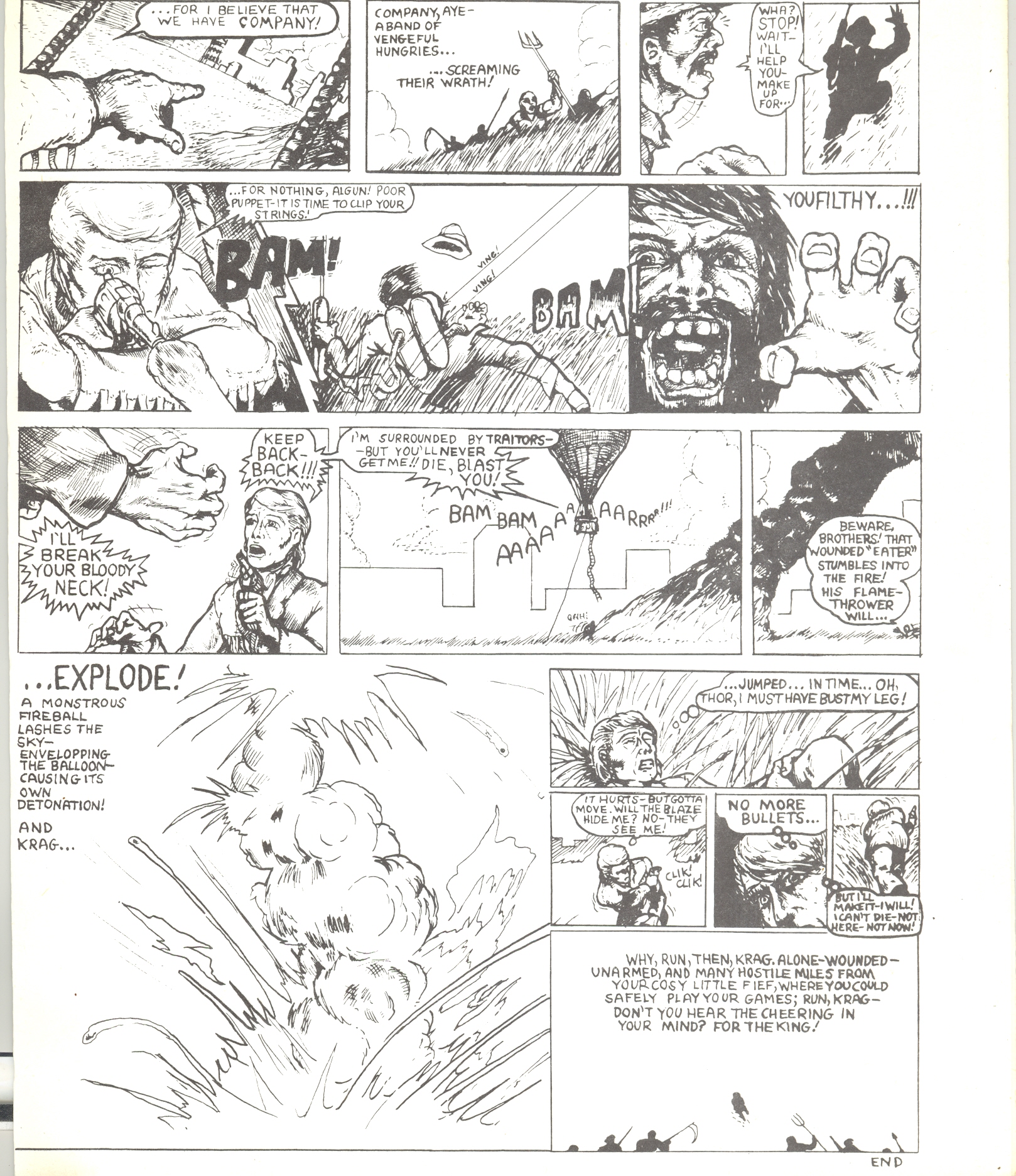

From here to the end, you’ll note that the panel-per-page ratio goes up, to as much as fifteen. Was this innovative structuring for more intense beats? No, it was bad planning. I leave the rest of the story to the masochistic blogreader. It depresses me to read it myself.

For the second issue I had simply mailed the pages to Ahmed in London and let him do it all himself. A bit cowardly of me.

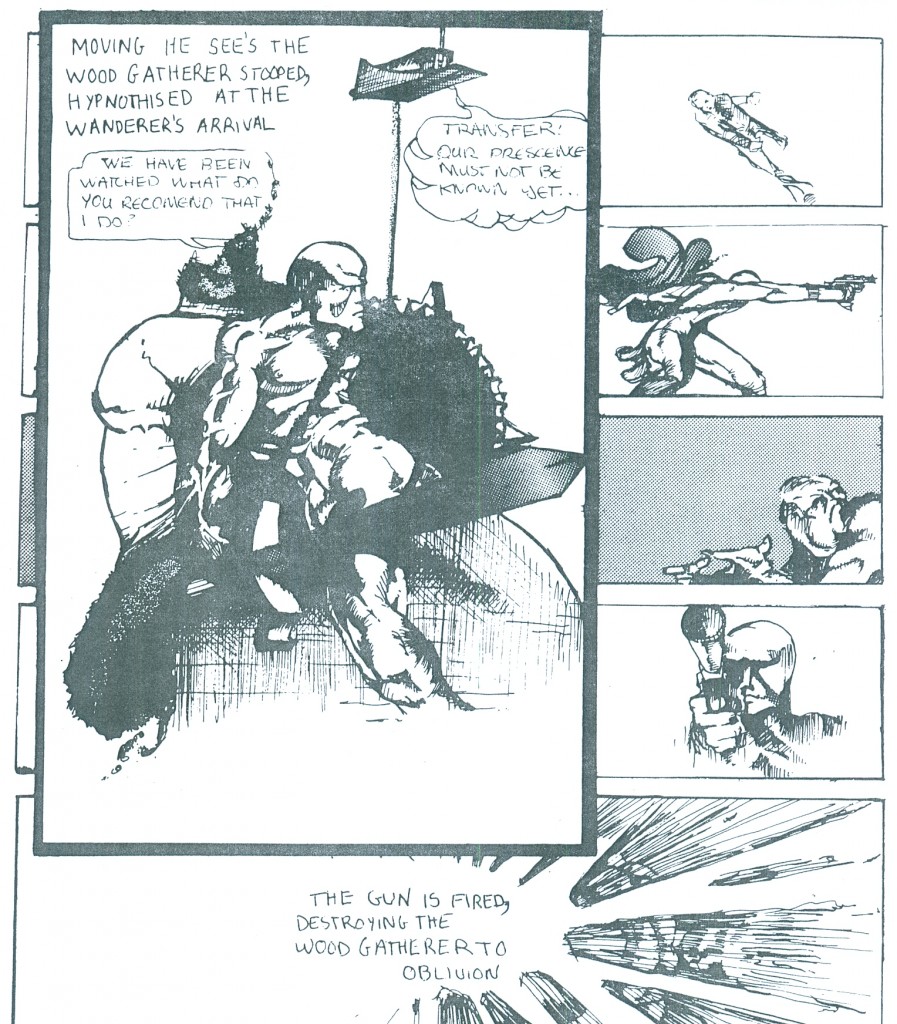

Ahmed found a 15-year-old artist named Marcelo Anciano to fill out the rest of the book:

When I finally met Marcelo the next summer, I remarked how his characters’ weapons were such blatant phallic symbols (see above). He nearly died laughing.

(Marcelo is now a film director and producer, working with Quentin Tarantino and other luminaries.)

Note in Marcelo’s back cover how he spells ‘Bizzaro’ for ‘Bizarro’. We were all over quality control, weren’t we?

The second issue was a sales disaster, as it probably deserved to be. I didn’t care; I’d purposefully disengaged myself from it, which was unfair and a betrayal to Ahmed and to Marcelo.

Today, Ahmed is known as Ahmed Shawki, the editor of the International Socialist Review. I wonder if our failed little business venture soured him on capitalism? He’s certainly grown since this first foray in the publishing business.

(One 13-year-old fan, an architect’s son, who used to come to Ahmed’s place where we’d discuss comics, was definitely not a business failure. He went on to found the Forbidden Planet chain of bookstores, the dominant direct-market distributor in Britain, and Titan Books. His name was Nick Landau.)

For years after, though, I’d take copies of issue 2 to the comics marts off Tottenham Court Road and vainly try to flog’em. This led to an embarrassing incident (and a good lesson.)

After one mart in 1975 I was hanging around while the organisers dismantled the set-up. A fellow dropped by the table where I sat and asked to see some of my purchases; we got to talking. It was Dave Gibbons, then known to me as a very prolific fan artist. He said he was working on superhero comics for an African publisher and was about to do ‘Dan Dare’ for an upcoming IPC mag called 2000 AD.

I passed him a copy of my issue 2 and awaited his opinion.

Now, Mr Gibbons is a gentleman, and I’m sure he didn’t wish to hurt my feelings. He pointed to one panel and said: “I like this one”:

As it happens, that panel is the only swipe I’ve ever done– stolen from Swamp Thing # 4.

” God sees the truth, but waits” goes the old Russian proverb.

So does Dave Gibbons! I’ve never swiped a drawing since. Never.

(“What, never?”

“No, never!”

“What, neverrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr….?”

“Well…

…hardly everrrrrrrrrrrrrrr…!!!

W.S.Gilbert, ‘HMS Pinafore’)

1973 was a watershed year for comics. And not in a good way.

The Underground smashed into a brick wall: anti-obscenity Supreme Court decisions, anti-paraphernalia laws that destroyed headshops, a general change in the culture away from perceived ‘hippie dippie’ values, all nearly killed this once-vibrant sector.

The great paper shortage of 1973 and the oil embargo of that same year put crippling pressure on the mainstream comics companies.

They also were losing quickly their traditional retail outlets, and the nascent direct market wasn’t yet strong enough to take up the slack.

Britain headed into a decade-long economic slump, putting paid to ‘swinging London’ (and birthing Punk.) ‘Dark they Were and Golden-Eyed’ went out of business in 1981.

promotional button by Hunt Emerson

Still, in those old crude fanzines of Britain’s early seventies are the seeds of future accomplishment. It was here that the young Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, Kevin O’Neill and so many others took their first stumbling steps.

Bram, Diane, Rob, Des– I just want you to know that the whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 15-year-old you knew as Alex is now a whiny, loud, obnoxious fanboy 56-year-old, and he’d like to buy you all a jar so we can lament how comics have gone to the dogs since our day. ‘When I were a lad…”

As for me, I never published again, and remain a dilettante in comics. Looking back, I regret that I didn’t pursue an entirely different talent I had for caricature; it would’ve borne more interesting fruit.

Ah, nostalgia just ain’t what it used to be…mais où sont les neiges d’antan? Where are the snows of yesteryear?

Below is a recent bit of foolery, done for an online ‘exquisite corpse’ jam comic:

That’s about the limit for me nowadays.

Yet, hard as I’ve been on my adolescent self — still I’d give up everything I have to relive those days, those golden years gone forever, when I was teenage cartoonist.

****************************************************************************************************

For a good overview of the British fanzine movement, check out

An incredible resource:

Lastly, that jam I contributed to: