In his recent piece decrying the comparison of comics to literature, Eddie Campbell, somewhat surprisingly, argues that it might be better to compare comics to jazz.

By way of a comparison, think of the great Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit”. It is a fine literary poem, set to music, and its author could have found no better singer to put it across. But a die-hard fan of Billie Holiday, the kind who has most of her recordings, is more likely to put on something from her earlier Columbia series of recordings, like “You’re a Lucky Guy” or “Billie’s Blues” (“I ain’t good looking, and my hair ain’t curled.”). A good number of the songs she had to sing during that period weren’t particularly good songs by high critical standards, and she didn’t have much choice in the matter, but the important thing is the musical alchemy by which she turned them into something precious. That and the happy accident of the first rate jazz musicians she found herself playing with, such as Teddy Wilson and Lester Young. Every time she sang she told her own story, whatever the material she was working with. I’m not talking here about technique, a set of applications that can be learned, or about an aesthetic aspect of the work that can be separated from the work’s primary purpose. The performer’s story is the essence of jazz music. The question should not be whether the ostensible ‘story,’ the plot and all its detail, is worth our time; stories tend to all go one way or another. The question should be whether the person or persons performing the story, whether in pictures or speech or dance or song, or all of the above, have made it their own and have made it worthy.

The truth is that this analysis is a little garbled. “Strange Fruit” is a mediocre song in no small part because the lyrics are lugubrious — the song’s lurid imagery and emotion sink into a clogged and ponderous earnestness. On the other hand, while it’s true that some of Holiday’s early sides weren’t especially great lyrically, many of them were. She sang “Summertime,”by Gershwin, arguably one of the greatest lyrics in the American songbook. She sang “A Fine Romance,” which means you get to hear Billie Holiday declaim, with great relish, “You’re calmer than the seals/In the arctic ocean/ At least they flap their fins/To express emotion.” She sang “St. Louis Blues” and “Nice Work If You Can Get It”. And, again, even a piece of fluff like the song “Who Wants Love?” is, in its simple unpretension, a good bit better lyrically than the overwrought “Strange Fruit.”

In other words, Campbell takes one of Holiday’s worst written song, declares it one of the best written, and then says that other tracks were better despite the writing rather than because of it.

But be that as it may. Let’s take Campbell’s contention at face value. We can look at “Who Wants Love?” which, as I said, doesn’t have especially great lyrics. “Love is a dream of weaving moonbeams in patterns rare/Love is a child believing/Stories of castles in the air” — that could be worse, but anytime you’re comparing love to moonbeams and having children build castles in the air, you’re not exactly in the realm of great poetry. So I think it’s fair to see this as an instance of a great artist trying to make mediocre material her own.

Campbell in his discussion seems to be suggesting that the content of Holiday’s songs is entirely beside the point; that the story, or lyrics, can be put aside, and the song can become purely about the artist’s achievement. But the achievement isn’t separate from the content…and Holiday doesn’t ignore the lyrics, or their slightness. Rather, her performance is in no small part about acknowledging and using the nothing she’s given. In her first words, she draws out that title, “Who wants love?”, putting more weight on it than the offhand phrase can bear — and so suggesting an intensity that can’t be contained in the song. That’s continued throughout; her exquisite sense of timing — swinging phrases so they stretch out against the beat — doesn’t ignore the song so much as emphasize her distance from it. She doesn’t mean what she’s saying, because what she’s saying doesn’t have enough meaning — not enough joy,not enough sorrow, not enough life.

The slightness of the song, then — its weak writing — becomes, for Holiday, a resource. And, as such, the weak writing is no longer weak. Holiday makes the writing mean more than the writer meant; it is not, as Campbell says, that she is telling her own story whatever the words say, but rather that her interpretation of the words is a great story. Campbell suggests that the song is not literary, but that Holiday makes it great anyway. What I’m saying, on the contrary, is that part of how Holiday makes the song great is that she transforms the words into great literature. And again, she does that not by ignoring what the words tell her — not by eschewing the literary — but by paying closer attention to what the words are saying and doing than the writer did, or than almost anyone can. Holiday’s triumph as a singer is in no small part her triumph as a reader — and as a writer. To deprive her of her literariness is I think in no small part to denigrate her art.

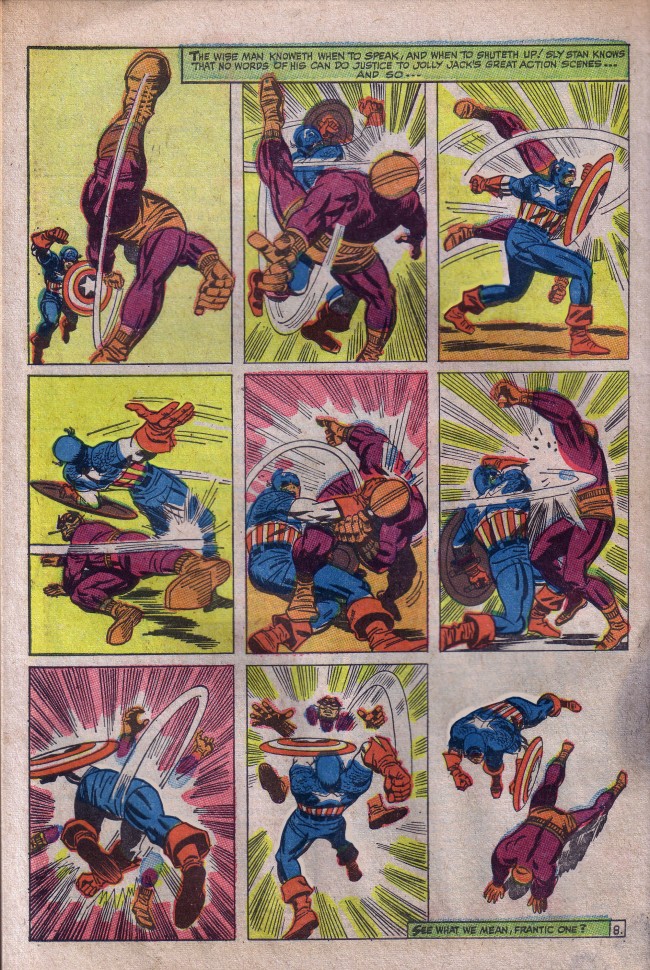

So let’s turn now to the Stan Lee/Jack Kirby page that Campbell presents as an example of counter-literariness and “improvisation” — a word that, coming as it does shortly after the discussion of Billie Holiday, can’t help but suggest jazz.

Campbell argues that this page is shaped importantly by the fact that it used the Marvel method. The art came first, and then the writing was done afterwards. Thus, Campbell argues, the Lee/Kirby collaboration “tends to elude conventional literary analysis.” For Campbell, the anti-literariness of the page is a result of process, and so the most important aesthetic content of the sequence, its most essential comicness, is dictated not by the creators, but by what are basically commercial logistics.

As I said,Campbell’s fear of, and misunderstanding of, conventional literary analysis reduced Holiday’s achievement. By the same token, his eagerness to place comics formally beyond the bounds of the literary denigrates the conscious artistry of Lee and Kirby. That’s in no small part because the conscious artistry in this page is precisely about addressing the literary.

Like the Billie Holiday song, the page’s narrative is pretty much empty genre default. Holiday used nuance and subtlety to explore the distance between her and her tropes. Kirby, on the other hand, employs stentorian volume to belligerently bash down the distinction between speech and noise altogether. The fight scene occurs nowhere in no space; the actors throwing themselves together in a series of almost contextless poses against a background of expressionist, blaring lines.Towards the end, Batroc starts to disappear altogether into the sturm und drung; his hands floating in an explosion of purple, his body returning to the white space that bore it.

Lee’s captions here, are, then, not mere filligree — they actually show a remarkable attentiveness to what Kirby is doing. As Campbell says, the captions establish additional characters — not just Cap and Batroc, but Jack and Stan, as well as the reader as audience. Moreover, Lee’s winking text boxes present the page not as a narrative about the battle between Cap and Batroc, but as a performance by Kirby (and, indeed, by Lee himself.) Thus, the heroic narrative is not about Captain America’s victory, but about Kirby’s Ab-Ex dramatic self-assertion — not about the triumphant outcome of battle, but about the triumphant rush of forms across the page.

Campbell, then, is right that Lee and Kirby are sidelining the superhero narrative. He’s wrong, however, to see that sidelining as formal or default. It isn’t that the comics form naturally or automatically eschews literariness. It’s that Lee and Kirby on this particular page are, very consciously, eschewing the literary. Campbell is in effect taking the particular achievement of Lee and Kirby, and ascribing it to comics as a whole. It’s like reading Moby Dick and concluding that literature is awesome because it has whales in it.

Moreover, while I think it is right in some sense to say (as I do above) that Lee and Kirby are turning away from the literary, it’s pretty important to realize that that turning away presupposes and requires a quite thorough investment in, and understanding of, the literary and how it functions in their art. In fact, I think that you get a better sense of what they’re doing if you see it, not as pushing aside the literary entirely, but rather as substituting one story for another.

Specifically, Lee and Kirby substitute for the story of Cap the story of Jack. The page is not about Cap’s feats, but — deliberately, insistently — about Kirby’s. Thus, the story Campbell tells about this page — that it is about Kirby and comicness rather than about Cap and his story — is itself a story. And it’s a story that Lee and Kirby are quite aware of, and which they deliberately chose to tell.

Which, since Campbell has raised the issue, brings up the question — how does the story Lee and Kirby are telling compare to the story Billie Holiday is telling?

For me, at least, the answer is clear enough. While the Lee/Kirby page has its virtues, the Holiday song is a much greater work of art. This is again, in large part, because Holiday and her band accept, understand, and then work with, the inconsequentiality of the song. Listen, for example, to the Bunny Berigan solo — all bright, brassy good spirits, until that final, wavering, hesitant dropping note reveals the cheer as a bittersweet facade. Berigan isn’t using words, but he’s absolutely telling a story — and that story is about how what the pop song can’t say is a song in itself. Tied up in the vapid tune, Berigan slips free by acknowledging that he can’t get free — his capitulation, his vulnerability, is his triumph.

Kirby’s insistent triumph, on the other hand, is his capitulation. There is no space in the Batroc battle for vulnerability or vacillation. Instead, the art booms out the greatness of Kirby without qualification — which is a problem inasmuch as the greatness is thoroughly and painfully qualified. The story Kirby is telling may be about his own mastery of form, but that mastery can’t escape from the stale genre conventions — and, worse, seems oblivious to its own hidebound inevitability. If Kirby is truly such a heroic individual, why does the individuality seem to resort to such half-measures? The art seems to boast of its thoroughgoing idiosyncrasy and extremity — but when it comes down to it, it won’t and can’t abandon the by-the-numbers battle for full on abstraction. Why can’t we just have bursts of colored lines in every panel? Why not turn the forms actually into forms, rather than leaving them as recognizable combatants? In this context, Lee’s captions almost seem like taunts, praising “Jolly Jack’s great actions scenes” as beyond words, when they are, in fact, perfectly congruent with the hoariest narrative clichés. The hyperbolic indescribable fight scene is, after all, just a fight scene. Holiday knows and uses the fact that her pop song is just a pop song, but Kirby the uncontainable doesn’t even seem to realize how thoroughly he has been contained.

You could certainly argue that the Batroc battle is more successful than I think it is. You might insist, for example, that Kirby’s struggle with the stupid superhero milieu is a kind of tragedy, and that the interest is in seeing him pull something worthwhile from the dreck. Again, that’s not exactly what I get out of it, but if you wanted to do a reading that told that story, I’d be willing to listen.

Whatever one’s evaluation of Kirby, there does in fact have to be an evaluation. If the point of art is to reveal whether the artist performing a story has made it their own and has made it worthy, then there has to be some possibility that the artist in question has not done either. But Campbell’s refusal to countenance comparison, his insistence that (following R. Fiore) comics are comics and that that is there main virtue, comes perilously close to making the comicness of comics their sole virtue. Comicness becomes the all in all — so that the production method of the corporate behemoth in whose bowels Kirby toiled becomes more important than whatever Kirby was doing within those bowels. In an effort to put Kirby beyond criticism by bashing literariness, Campbell paradoxically ends up elevating the genre narrative, with no way to praise Kirby’s efforts (successful or otherwise) to leave those narratives behind. If literature has nothing to do with comics, then Kirby’s efforts to blow up genre narrative into abstraction and form become meaningless. If Kirby can’t fail, then he can’t succeed, either.

The truth, of course, is that art simply isn’t segregated the way Campbell wants it to be. There is literariness in comics, just as there is rhythm in prose and imagery in music. Artists — even comics artists — don’t fit themselves into boxes. Why shouldn’t a singer or an artist tell stories and think about narrative? What favor do you do them by pretending that they can’t or won’t react to and use the words and the narratives that are part and parcel of their chosen mediums? I like Kirby less than I like Billie Holiday, but both of them are greater artists than Eddie Campbell will allow.

_____________

You can read the entire roundtable on Eddie Campbell and the literaries here.