Can a black man stand for America?

Barack Obama is one answer to that question — and a somewhat complicated one given the conspiracy theory birther nonsense that has been belched up in the wake of his presidency. Another answer is the upcoming Captain America arc, in which Sam Wilson, formerly the Falcon, is going to don the Cap uniform.

We don’t know yet how Marvel will approach the issue of a Black man as an icon of Americanness. But we do know how they addressed it once before, in the 2003 mini-series Truth: Red, White, and Black — a mini-series written by the late Robert Morales and drawn by Kyle Baker. Morales and Baker have very specific, very complicated thoughts on what it means for a black man to be America — and most of those thoughts are really, really depressing.

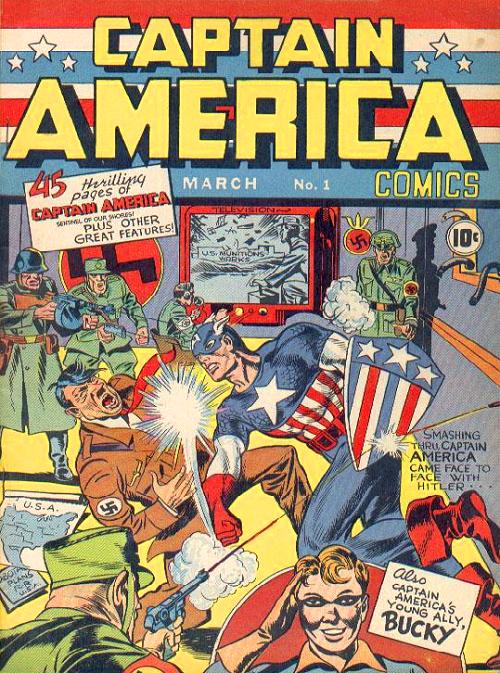

To understand what Morales and Baker are doing in Truth, you have to recognize that not just Captain America, but superheroes more broadly, have from their inception been obsessed with Americanness — and with assimilation. The Jewish creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster inaugurated the genre with an immigrant from another planet who is adopted by friendly middle-Americans, and becomes the perfect, iconic personification of American strength and the American way. The Clark Kent identity can be seen as a kind of buried Jewish self, uneasily replicating stereotypes about emasculated, nerdy Semites. That’s true for Captain America too, to some degree. Created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, both Jews, the weak, spindly non-manly Steve Rogers takes the magic super-soldier formula and becomes the ur-American. More recently, G. Willow Wilson has played with this in Ms. Marvel, creating a young Muslim girl who (at least in the first few issues) transforms into a blonde-haired white-skinned Caucasian when she goes superheroing. Gene Luen Yang and Sonny Liew take a related tack in The Shadow Hero, drawing parallels between their Chinese-American hero’s embrace of superheroics and his embrace of Americanness.

Assimilation fantasies can work for Jews and, arguably for Asian-Americans and Muslims. But they don’t necessarily work for black people. Black folks came to America long before my Jewish family did — but me and Stan Lee (neé Stanley Lieber) are white now, and black people are still black. A superhero fantasy about gaining powers and becoming Ameican which acknowledges the black experience, then, is going to be more difficult, and potentially more bitter, than superhero fantasies that are focused on the experiences of other immigrant groups.

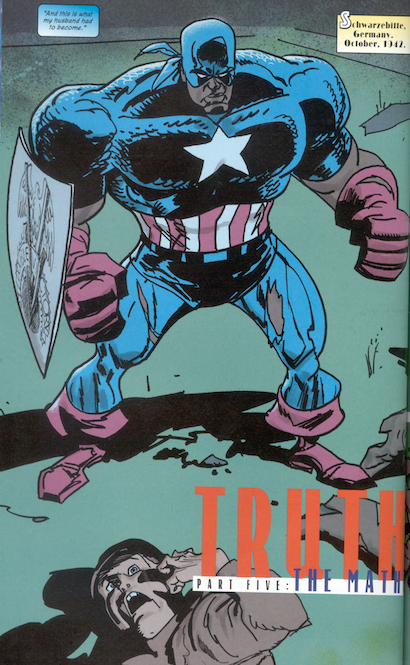

Truth is both difficult and bitter. The story is set in Marvel continuity after Steve Rogers has become Captain America, and after the creator of the super-soldier formula has been shot. The U.S. Army is experimenting with trying to recreate the formula — and, in a nod to the horrific Tuskegee syphilis experiments, the subjects it chooses to experiment on are black soldiers. Without anything like informed consent, the soldiers are injected with versions of the formula. Most of them die, literally exploding. Most who survive are deformed and twisted, as Kyle Baker makes full disturbing use of his talent for plastic, exaggerated cartooning. These twisted supersoldiers are used as cannon fodder, or destroy themselves because of the emotional instability caused by the drug.

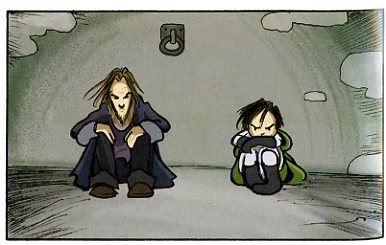

Eventually only one man is left, Isaiah Bradley. He goes on a suicide mission to disrupt the Nazis own supersoldier formula — wearing an extra Captain America uniform he stole. After succeeding in his mission, he is captured, and miraculously escapes, at which point the U.S. military arrests him for taking the costume and puts him in solitary confinement for over a decade. The supersoldier formula damages his brain; the government refuses to treat him, and he ends up with the mind of a child. End of heroic parable.

In a lot of ways, this is an assimilation narrative. A black person, like the (somewhat but not all that subtextual) Jewish person before him, takes the supersoldier formula, and gets to become that icon of the United States, Captain America. But that story of triumph and belonging is tragically warped — and the name of that warping is racism. Black men are seen by the army and the United States as disposable, inferior subhumans. Becoming American, for them, means being enslaved, tortured, and killed. Isaiah Bradley can claim his Americanness by putting on the Cap uniform, but America is too dumb to be honored. Instead, it does to Bradley what it has done to thousands of its black citizens; it puts him in prison.

The story, then, is about the way that black people are not allowed to assimilate, and not allowed to become American heroes. But it’s also, and at the same time, an indictment of what is being assimilated to, and of assimilation itself. James Baldwin famously asked, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?” and Truth poses the same pointed question. The U.S. is in many ways shown to be little different from Nazi Germany. Like the Nazis, the U.S. performs hideous medical experiments on what it considers to be inferior races. Like the Nazis, the U.S. engages in mass slaughter; the armed forces are shown indiscriminately murdering black soldiers because it perceives them as a security risk — and though this is based on a probably untrue apocryphal incident, it stands in easily, and accusingly, for long-term American mass violence against black people from slavery through Jim Crow and beyond. An American seen through the eyes of the black experience is an America steeped in racial bigotry and violence. It’s not a heroic America, nor one that deserves either loyalty or respect. From this perspective, the Superman and the Nazi Ubermensch are two sides of the same spandex — both champions of racism and evil. Assimilating to that doesn’t make you a hero. It makes you a monster.

Morales is quite direct about the parallels between the United States and Nazi Germany; he talks about America’s pre-war embrace of eugenics, and notes that U.S. racist immigration policies were an inspiration for Hitler’s own state-sponsored racism. Ultimately, though, at its end the comic rejects its more radical stance, and re-embraces both superheroes and assimilation. Steve Rogers shows up in the present (fresh from suspended animation) to track down and punish a couple of racist military personnel who are presented as being responsible for the experiments. The institutional critique of the earlier part of the book is shuffled out in favor of revenge on individual bad guys.

On the one hand this seems like a compromise or a capitulation to the superhero narrative, with Captain America as the superhero ex machina who swoops in to save, not Bradley, but the idea of America’s goodness and strength. Bradley, childlike, seems overjoyed when Cap hands him his old torn costume, as if it’s his fondest wish to become part of the country that’s systematically, brutally, for decades, spit on him and ruined his life.

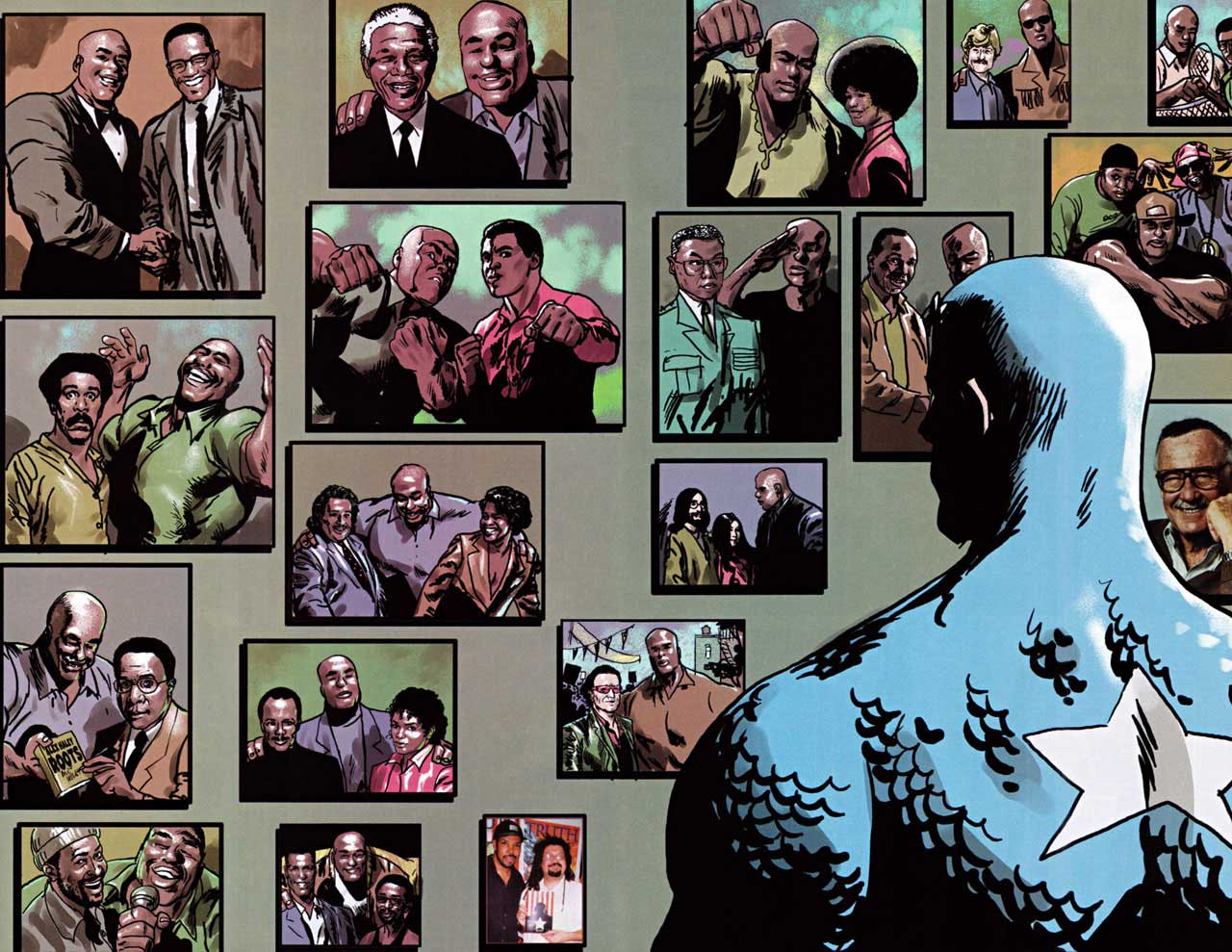

It’s also possible, though, to see the ending not as Bradley assimilating to America, but as America assimilating to Bradley. “I wish I could undo all the suffering you’ve gone through. If I could’ve taken your place…” Cap says to Bradley’s blank stare. That’s impossible, of course. Cap can’t be black. But the point of the comic, too, is that Cap can be black — and that he is black. The final image of the series, with the two Captain Americas photographed together, might be seen as Bradley finally being allowed into America. But it also recalls an image from a few pages earlier. There Cap stopped to look at a wall of images of Bradley photographed with Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Angela Davis, Richard Pryor, Muhammad Ali— a who’s who of black America. In seeking Bradley out, and honoring him, Cap is placing himself on that wall, with those pictures. Rather than Bradley becoming American, Captain America is becoming, or joining, black America. Justice, truth, and heroism come not through assimilating to white America, but through accepting and honoring the experiences of the marginalized.

Is that an insight, or an approach, that Marvel is likely to pick up for its new Captain America run? We’ll have to wait and see. In the meantime, it would be nice if Marvel would reprint Truth — one of those rare superhero comics that sees clearly what’s wrong with the genre, and what could, maybe, be right.