by James Romberger

“Ants are the only insects to keep pets, use tools, make war and capture slaves.” — David Wojnarowicz

A Fire in My Belly, a film with a depiction of fire ants swarming over a crucifix, was removed from the Hide/Seek exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian through the intercession of the president of the Catholic League, William Donahue and the Ohio Republican and House Minority Leader John Boehner, who had not seen the film in question. In the center of the current controversy over this act of censorship is the late artist David Wojnarowicz, who did attack the Catholic Church and other politically active religious institutions repeatedly—and for good reasons.

David’s oeuvre was never only about his reactions to organized religion, nor was it ever only about the AIDS crisis. Certainly the disease that would kill him in 1992 gave his work a powerful impetus, but David always took a greater global view. He examined the way that the natural world works and how our relationships with each other and the planet fit within the continually shifting narrative of history. He also expressed a complex interiority as he engaged with different media to make his sometimes lyrical, sometimes enraged or explicit, but always thoughtful and heartfelt art.

David took on heroic proportions because of his outspoken response to the AIDS epidemic. He watched his friends falling around him. After his own diagnosis in 1988, he made a concerted effort to understand the disease and to combat the people and institutions that he was able to identify as enablers of the virus through their homophobia and suppression of information. David protested the New York archdiocese with Act-Up at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, for the Church’s closure of health care clinics in the middle of an epidemic and for their condemnation of condoms, safe sex, birth control and reproductive rights. When in 1989 David described Cardinal O’Conner as a “fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas up on fifth avenue” in his essay for the catalog of Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, a exhibition funded by the NEA, he faced censorship and a subsequent national reaction not unlike the current turmoil.

But even earlier, in 1986 and 1987 as he watched his mentor, the photographer Peter Hujar, waste away and die, David believed the Roman Catholic Church had abandoned everyone he loved. He knew that some gay men find closeted refuge in priesthood, while their Church publicly preaches against homosexuality. David wrote in a biographical outline that he “remembered beatings and having to kneel on bags of marbles” in Catholic school at the age of eight. The imagery of Catholicism suffused his work from the beginning. David’s friend and my partner, the interdisciplinary artist Marguerite Van Cook says he had “a crisis of faith,” certainly his beliefs were sorely tested. He knew even then of the widespread pedophiliac component of the Church, and mentioned to us that he knew the infamous Father Bruce Ritter of Covenant House. In 1990, Wojnarowicz became national news once more after his work was used by the Reverend Donald Wildmon’s American Family Association to lobby against NEA funding for the arts. After successfully suing the Christian fundamentalists for defamation, David posed questions about the separation of church and state:

“Do some politicians have a direct communication with God?…Should one person’s interpretation of God determine whether another person lives or dies?…How many members of minorities are afraid to speak if they think they are the only ones who feel the way they do?…Does the denial of information that causes people to become ill and die a permissible thing?…Would it be a crime if that denial of information only killed people you didn’t feel comfortable with?”

A Fire in My Belly has been defended as being about AIDS and not about his anger towards the Church, but David’s later motivations should not be retrospectively applied to a film that he made earlier. The Smithsonian has posted a “Q&A” on their website which claims, “This imagery was part of a surrealistic video collage filmed in Mexico expressing the suffering, marginalization and physical decay of those who were afflicted with AIDS.” However, what is being shown on Youtube and elsewhere online is not the original film, its intent has been changed because elements have been added that are misplaced in time. The versions in circulation now both have imposed soundtracks and their meaning is altered with added imagery that was made years later. David made A Fire in My Belly in 1986, before he was diagnosed with AIDS.

I am one of the few who saw David’s original film. He showed it to me privately at his apartment (formerly Hujar’s residence, over the movie theater on 2nd Avenue) in 1987 when we began collaboration on our graphic novel Seven Miles a Second. He had me sit in front of his big TV, next to his baby elephant’s skeleton and insisted that I watch his Mexican film. What followed was an assault on my senses, a view of a world completely out of control. The strobed, often violent scenes of wrestlers, cock and bull fights, lurid icons, impoverished dwellings, clanking engines, an enslaved monkey, cripples begging for coins, for bread, a burning, spinning globe—it was a picture of indifference to the value of life, Mexico as a grinding machine of poverty and cruel spectacle. I didn’t enjoy the experience. The images and soundtrack combined to create a powerful feeling of unease and angst. I was obviously shaken as it ended, but David just laughed. We moved on to discuss our intention for the comic book, still the afteraffects were hard to shake. He told me later that he had disassembled that first version.

The film in all its incarnations connects strongly to Mexican Diaries, the second show David did at Ground Zero, the gallery that Marguerite Van Cook and I co-directed from 1984 to 1987 (obviously, named long before 9/11). David showed with us because he liked our own artwork and because we offered him shows unfettered by any restraints at a time when he was disillusioned with the art world system. In their quest for success, the galleries of the East Village were turning away from their initial wildness. The Neo-Geo movement encouraged highly polished presentations, more like the staid Soho scene that we all reacted against in the first place. Marguerite embodies the punk ethic of embracing change and encouraged our artists to make concise conceptual statements as gallery-transformative installations. For my part I wanted their most intense expression, to befit a gallery called Ground Zero, the epicenter.

David’s first show with us in December 1985, You Killed Me First, gave us both our wish. It was a horrific, anti-commercial installation that David said had an intended similarity to Marcel Duchamp’s voyeuristic final work. The gallery was made over to resemble an empty garbage-strewn lot, lit only by a broken window. The patrons could enter this forbidding alley to look though the window and see a scene that resembled a panel from E.C. Comics’ Tales from the Crypt. Three dessicated corpses sat around a decomposing thanksgiving feast, their blood spattered on the walls, while a TV in the corner played a looped film, also titled You Killed Me First.

The Cinema of Transgression’s most sophisticated photographer, Richard Kern, directed the film that stands as one of the most effective works of the entire movement. David channeled his own father to play the violent patriarch, while Karen Finley did a piercing performance as the mother. An ingenue called Lung Leg played their gothish daughter. After a series of conflicts with her family, the girl murders them all at dinner. The installation was contextualized by the film, which revealed to the viewer that the putrid crime scene before them was the result of a violent reaction to bullying and abuse. Also, David in effect kills his Dad and himself, since it is his cadaver slumped to the right.

In Semiotext(e), David’s confidante, the photographer Marion S. expressed the artist’s satisfaction with the piece: “he really loved making that movie with Richard…and the installation at James and Marguerite’s that related to the film. It was so scary, so great, and so exciting.”

For his next solo show at Ground Zero a year later, David made five paintings. They were inspired by a trip to Mexico where he shot A Fire in My Belly, his next film project. Mexican Diaries opened in January of 1987, so the images in the show were all painted in 1986, despite the later dating that has been ascribed to them in books about David. The paintings share their imagery with the film, which is dated in its credits as done in 1986.

You Killed Me First, installation views, 1985.

The paintings and the film inform each other. Portrait of Bishop Landa, the painting with the paper-mache head of Jesus seen exploding in the video, had a substantial number of live fireworks glued to it. The opening reception for the show was packed. We had to guard the painting against the self-immolating artist Joe Coleman, who insisted in lurking nearby, waving his lit cigar. The piece survived the opening, only to be destroyed for the filming of A Fire in My Belly. Our slide shows the relationships between the painting and the film, in the prominent fire-breather, also seen to dramatic effect in the film, in the overarching intent of the piece as a portrait and in the significance of its destruction.

Portrait of Bishop Landa. Mixed media, 1986.

Bishop Landa is profiled on Wikipaedia:

Diego de Landa (12 November 1524–1579) was a Spanish Bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Yucatán. He left valuable information on pre-Columbian Maya civilization, and…destroyed much of that civilization’s history, literature, and traditions…Landa was in charge of bringing the Roman Catholic faith to the Maya peoples after the Spanish conquest…After hearing of Roman Catholic Maya who continued to practice idol worship, he ordered an Inquisition in Mani ending with a ceremony called auto de fé. During the ceremony on July 12, 1562, at least forty Maya codices and approximately 20,000 Maya cult images were burned.

Portrait of Bishop Landa was a literally explosive piece about the destruction of culture as a means of control, in other words, about censorship. David uses Landa to represent the way the Church’s views are still pressed on the world. Landa takes on the face of Christ to do violence. Christ breaks out of the flatness of the painting, the modern, the 3-dimensional supplants the flat visual iconography of the Incan civilization. It is a collision of cultures, each with their own chaotic violence. In the film, David consigns religion with its politics and theater, its suffering and sacrifice to the flames.

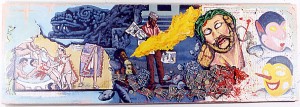

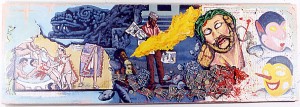

Mexican Crucifix, acrylic and collage on panel, 1986

The large multitych Mexican Crucifix furthers the theme that Catholicism functions in Mexico as a means of control, to indoctrinate people from a young age through just enough religious education to have a passive acceptance of their state of poverty and ignorance. The religious components in the paintings of Mexican Diaries are more prominent than any reference to AIDS, and this could also be said of his original version of A Fire in My Belly.

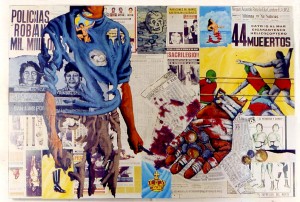

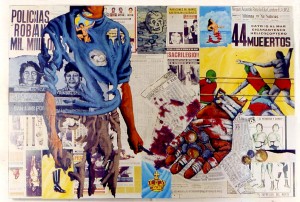

A large piece called Street Kid that alludes to David’s own often-homeless adolescence was papered with Mexican wanted posters and overlaid with wrestling graphics and a giant bandaged hand holding a few coins that is seen in the Youtube edit of the film. The painting was reproduced in the Art In America review of our exhibition, but years later I saw it again in the back room of PPOW and it had been completely altered. David had covered the entire piece with a dense lattice of winding green vines, nearly obscuring the original image.

Street Kid, acrylic and collage, 1986

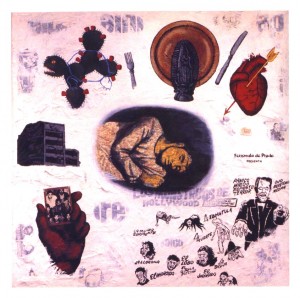

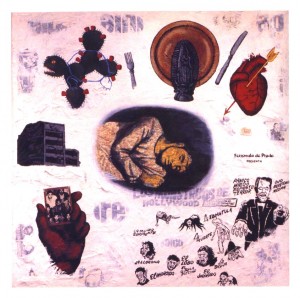

David began his travels in Mexico with filmmaker Tommy Turner. In our show was a painting called Tommy’s Illness, a pale color field with the likeness of our mutual friend sleeping in the center while eidetic imagery floats about him: a place setting, the meal a Virgin Mary icon, a linear turtle superimposed on a cactus, a heart with an arrow through it and a procession of monsters such as Frankenstein. At Ground Zero, a Mexican marionette identical to the one seen dancing and burning in the film was suspended over the painting as part of the work.

Tommy’s Illness (Mexico City), acrylic and collage, 1986, sans marionette.

David wrote that driving through Mexico, he felt as if he was “passing through the future of New York City…rolling through neighborhoods more and more desperate until suddenly in the middle of it all we rolled into a spanking new section.” He describes “a day filled with rich people and poor people; a day of diamond rings on lifeless fingers, a day of armless and legless men in the dawn…” He later worked on various photomontages using isolated imagery from the footage he shot there. He made a tiny painting of a suited organ grinder’s monkey, also seen in the film, that he told us was Hujar’s favorite of the pieces in the show.

Untitled, acrylic, 1986

There was a soundtrack on the film David showed me in 1986, he turned it up loud. The original score was a collection of his tape-recorded incidental noise mixed with snatches of industrial music, which was equally as chaotic as the images. It was not the tape-recorded ACT-UP demo that the National Portrait Gallery’s curators added to their edit. The Diamanda Galás score that is attached to the Youtube version is also a later addition, but one which is more in keeping with the feel of the original soundtrack. According to the Washington City Paper, Galás’ “music was part of a seven-minute edit of the 13-minute work made after Wojnarowicz died in 1992.” But, Galás was David’s friend and the symbolism she adds is apt:

“THIS IS THE LAW OF THE PLAGUE was composed in 1986. I will presume this is the music composition upon which David’s film FIRE IN THE BELLY was based, or with which he felt a strong affinity…My liturgical treatment of LEVITICUS is a march of the priests and lawmakers forcing the unclean from the gates of the City into warehouses out of town, and is very gently illustrated by David’s depiction of the crucified Christ covered with ants. Ants are only one of the many insects and animals that would cover a man removed from his village and deposited in a leper asylum.”

David’s original title and the Youtube version with a detail of Street Kid

When David shot the film that he used in A Fire in My Belly, he was traveling through Mexico shooting whatever caught his eye. He made a script for editing purposes (with no indications for the soundtrack) which is in the collection of NYU’s Fales Library, along with the fragments of David’s film that were chosen for the exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery by curators Jonathan Katz and David C. Ward. I have not been able to find information about their process to know if Katz and editor Bart Everly used the script to guide the editing of their version.

I did once see a document that David made for a film that was left in the care of his friend and collaborator Marion S. It was a very carefully worked-out storyboard elaborating how disparate bits of film would be montaged, to form a sort of moving version of what his later photographic art pieces look like, the ones that have the circular insets, i.e. all parts of the film would be moving and shifting, within the insets as well as the overall backgrounds. Marion says that “life didn’t give us enough time to go through with the project.” She prefers not to continue a joint work in the absence of her partner.

But not everyone is as concerned as Marion with ensuring the integrity of David’s art. Even before the film was removed from the show, David’s voice had been recontextualized. The Smithsonian’s curator Katz says that the film was “edited in terms of length, not to remove content. We felt the imperative to represent David Wojnarowicz’s work as he designed it. We included every scene that’s in the video, we just truncated the length.” Notwithstanding this explanation, the fragments of A Fire in My Belly from the Fales collection were altered and an anachronistic soundtrack was added to a film that was thought to be silent. The images of David with his lips sewn shut are also misplaced in time. They are from Rosa von Praunheim and Phil Zwickler’s 1989 film Silence=Death and impose a focus on the AIDS crisis on a work from a time just before David primarily dedicated his work to his ordeal with AIDS. Unfortunately, some of the response to the Smithsonian’s subsequent removal of the film from Hide/Seek has thus far also suppressed David’s intent regarding religion.

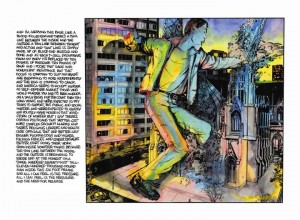

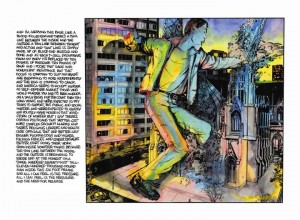

David said, ‘Draw me huge, smashing 5th Avenue.’ From Seven Miles a Second, 1996.

David Wojnarowicz’s own feelings about nationalism and the imposed borders of “the preinvented world” aside, he was a great American artist and so his work has a place in any institution dedicated to presenting and preserving the American experience. It would be difficult if not impossible to find a work by Wojnarowicz that does not address religion on some level, let alone other controversial issues. Still, whether or not freedom of religion entitles religious institutions to be exempt from criticism should be subject to debate, as well as if the Smithsonian failed in their trust.

__________________________________

Photographs by Karen Ogle

You Killed Me First David Wojnarowicz w/Richard Kern, Ground Zero, 10/12/1985-1/05/1986

Mexican Diaries David Wojnarowicz, Ground Zero, 1/07/1987-1/25/1987

Courtesy of Ground Zero/The Arteries Group

A Fire in My Belly copyright 2011 by the Wojnarowicz Estate

Wojnarowicz’s final painting: Why the Church Can’t/Won’t Be Separated from the State. Mixed media, 1991. Courtesy of PPOW and the Wojnarowicz Estate.

Seven Miles a Second copyright 2011 by Romberger /Van Cook and the Wojnarowicz Estate

____________________________________

SOURCES

David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years on the Lower East Side. Interviews by Sylvère Lotringer. Ed. Giancarlo Ambrosino. NY: Semiotext(e), 2006.

Scholder, Amy, ed. Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz. NY: Rizzoli, 1999.

Smith, Paul, “David Wojnarowicz at Ground Zero,” Art in America, 9/1987, pg. 182-83.

Wojnarowicz, David. “Postcards From America: X-Rays from Hell.” Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (catalog) NY: Artist’s Space, 1989.

Wojnarowicz, David. In the Shadow of Forward Motion (catalog). NY: PPOW, 1989.

Wojnarowicz, David. Tounges of Flame. (catalog) Illinois State University, 1990.

Wojnarowicz, David. Brush Fires in the Social Landscape. NY: Aperature, 1994.

Wojnarowicz, David, James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook. Seven Miles a Second. NY: DC/Vertigo Verite, 1996.

Diamanda Galás’ statement about A Fire in My Belly

Q&A with “Hide/Seek” curators Jonathan Katz and David C. Ward

Smithsonian Q&A Regarding the “Hide/Seek” Exhibition

Wikipedia on Bishop Landa