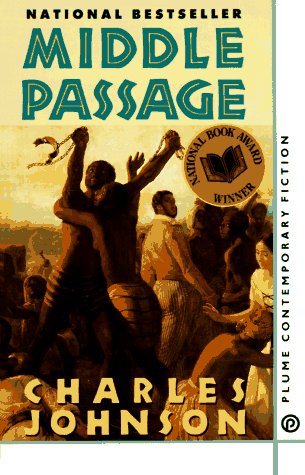

Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage is structured as, and by, a romance. The novel starts off with a description of the relationship between freed slave, thief and wastrel, Rutherford Calhoun, and the prim schoolteacher Isadora Bailey. Calhoun and Bailey are in love with each other, but he’s not willing to be tied down; she forces the issue by offering his creditor, Papa Zeringue, to pay his debts if he’ll marry her. Zeringue determines to force Calhoun to do just that, but he slides out of the ring or the noose or whatever metaphor you wish by sneaking aboard an illegal slave ship bound for Africa. Adventures and hijinks ensue…but in the end his travails and misfortunes bring him back around to Isadora, and the book ends, as romances should, with a marriage and happiness.

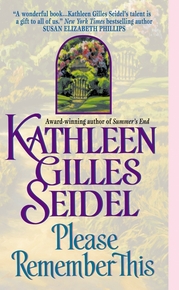

Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s Please Remember This isn’t really structured as, or by, a romance. There is a romance in it — between coffee-shop owner Tess Lanier and historical excavator Ned Ravenal. That romance, though, doesn’t really get started until something like 2/3 of the way through the book. The bulk of the earlier part of the novel, and the main thrust of the plot, is about Tess’ relationship with her dead mother, the brilliant author Nina Lane, who killed herself several months after Tess was born. The novel meanders through it’s small as life, non-adventurous plot, letting Tess figure out that she doesn’t have to be Nina, and doesn’t have to not be Nina, before getting her to a place where she can take up the rest of her life — which, almost as an afterthought, involves Ned.

Both of these books in broad terms fit into Pamela Regis’ eight essential elements in “Natural History of the Romance Novel,” but Johnson’s book is much more insistent about it — the action in the novel all derives from the development of the romance, whereas for Seidel the bulk of the novel’s structure and themes would be little changed if Tess had just recommitted herself to her coffee shop at the end, rather than finding a man immediately. Yet, “Middle Passage” is generally considered a work of literary fiction, while “Please Remember This” was marketed as a romance novel. What’s with that?

Part of the answer is right there in that last bit; Seidel is a romance novelist and marketed as such, so her book is considered a romance. Johnson writes literary fiction, so his book is literary fiction. In genre, form is less important than commercial labels.

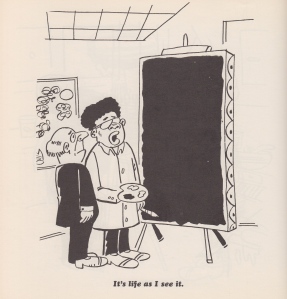

There’s some more to it than that, though, I think. Middle Passage presents itself as literary fiction in a number of ways — most insistently in its prose. Seidel’s prose style is accomplished, precise, and frequently delightful; “It was part rock festival, part Star Trek convention, and part plain old down-home country fair without the baby pigs and homemade jam” is an imaginative and funny first line. It’s significantly less performative than Johnson’s opening, though:

Of all the things that drive men to sea, the most common disaster, I’ve come to learn, is women. In my case, it was a spirited Boston schoolteacher named Isadora Bailey who led me to become a cook aboard the Republic. Both Isadora and my creditors, I should add, who entered into a conspiracy, a trap, a scheme so cunning that my only choices were prison, a brief stay in the stony oubliette of the Spanish Calabozo (or a long one at the bottom of the Mississippi), or marriage, which was, for a man of my temperament, worse than imprisonment — especially if you knew Isadora.

It’s not coincidental here that the virtuosity here, the hyperbolic/mock-hyperbolic irony, is achieved through riffing on misogynist tropes. Isadora becomes a disaster, a conspiracy, a trap, a scheme — she’s a placid nonentity on which to embroider flights of cheerfully rhetorical antipathy. That is more or less the case throughout the novel, in which Isadora serves mostly as a plot device. We don’t see into her head, and while our protagonist/narrator Rutherford says he loves her, we get much less of a sense of his relationship with her than of his attraction/repulsion to the Bly-like Captain Falcon, or the Allmuseri tribe members who have been captured and enslaved on ship. The romance with Isidora is the impetus and the structure of the book, but Isidora herself is mostly a trope — a stand-in for the world of home from which you set sail and then return (Johnson explicitly compares her to Penelope.) Even her body becomes subordinate to the plot and Rutherford’s attitude towards her; she loses 50 pounds while he’s away at sea, physically demonstrating her transition from disaster to desirable in Rutherford’s eyes, though how she feels about the change is never either mentioned or considered. The book’s literariness, it’s (multiple, deliberate) textual links to the Odyssey, Moby Dick, Joseph Conrad, are based on repressing or displacing the romance plot that guides it in general, Isadora’s consciousness in particular.

In this regard, it seems important that Rutherford’s main internal conflict involves his feelings for his brother, and especially for his father, a slave who escaped and left his sons behind him. Rutherford has always bitterly resented being abandoned, but after a traumatic encounter with a kidnapped, delightfully Lovecraftian African God, he understands that his dad never came back to visit because he was killed by patrollers almost as soon as he tried to escape. The recognition that his father didn’t abandon his responsibilities, but was murdered out of them, allows Rutherford to accept responsibility himself (after a good deal more trauma.) Which is nice for him, but leaves another question unanswered, and almost unasked — viz., even if he barely knew his mother (she died when he was 3), why doesn’t he, or the book, seem to care about her at all?

You could ask the inverse question of Please Remember This. Tess is tied in knots about her mother, the brilliant, erratic Nina Lane — where Rutherford can’t settle down (it’s implied) because of his father’s shiftlessness, Tess is too settled as a reaction to her mother’s eccentricity. And where Rutherford doesn’t seem to care about his mother, Tess is similarly disconnected from, and uninterested in, her father. Early on, we learn that the man she thought was her dad, wasn’t; Nina had conceived Tess not with her then-boyfriend, Duke Nelson, but (maybe? possibly?) with some passing-through hipster artist dude, who Tess never even bothers to try to track down. Instead, rather than looking for fathers, Seidel multiplies mothers, focusing on Nina Lane’s relationship with her own mother, Violet, who raised Tess, and with one of Nina’s friends, Sierra, who cared for Tess for the first couple of months of her life,and wanted to keep her.

In Middle Passage, Johnson suggests that the Lovecraftian African God may control multiple worlds and multiple realities, and Rutherford imagines himself as the captain and the captain as him, the hold crammed with “white chattel” — a vision of racial poles reversed, but also of Oedipal substitution, with Falcon serving as a sinister father figure, the twisted European forebearer (Conrad? Lovecraft? Melville?) in whose stunted footsteps Johnson ironically but inevitably treads. In Please Remember This, on the other hand, narratives are composed not of alternate fathers, but of alternate mothers. Tess sees herself, or her possible selves, in the mother/daughter relationship in Nina’s last, unfinished novel; in the actual relationship between Nina and her mother, Violet; in the possible self Tess could have been if Nina’s mother had raised her:

And what would being raised by Sierra have given Tess?

She might not be as independent as she was now. She might not be as observant or as serene. She might not have been allowed to develop her own style and her own voice.

But she might have had the capacity to love Ned Ravenal as he deserved. And that would have been good.

“We might have done all right together,” Tess heard herself say to Sierra. “We might have done all right.”

The phrase, “Tess heard herself say” is a good example of Seidel’s subtlety. Tess is imagining herself as someone else, and then she speaks as someone else, as if the other she might have been is talking through her. It’s a quiet nod, too, to reader, and author, identification — we, after all, are both identified with Tess, and hearing her speak. The novel becomes a way to imagine other mothers, other lives, and to think how we might have been someone else, and done something else, and loved someone else. Though for Tess, in the end, imagining that someone else she could be allows her to love as she thought only that someone else could.

The reason that Seidel’s book is romance, then, is because it cares about dead mothers; Johnson’s is literary fiction because it cares about dead fathers. And that’s also, perhaps, why Johnson’s feels more formulaic — more wedded to both the romance narrative and, contradictorily, to the performance of genius that signals literary fiction. Supplanting the father is an old story, in which the new boss is always already the old boss and vice versa — like Isadora or Penelope, you unwind the thread each night only to rewind it the next morning, waiting for the guy to return. Mothers, though, in Seidel’s vision at least, don’t replace each other, or duplicate each other, but multiply possibilities. Different loves are different, which is how a novel which isn’t a romance can be a romance, too.