This was originally printed in The Comics Journal, later at Eaten By Ducks, and I’m reprinting it here again in case Theresa, Tucker, or either of my other regular readers happened to miss it.

Charles Schulz was not a fan of underground comics. He thought they were vulgar and boring. “What was strange about them,” he said in an interview with Gary Groth, “was they pretended to be so different and they all turned out to be the same…. What’s so great about that?”

Schulz was referring to an earlier generation of alternative comics, of course. The horny ’60s shock-jocks Schulz despised have long since given way to legions of sensitive new-age artistes selling a very different brand of self-indulgence. And while older underground icons like Harvey Pekar may have sneered at Schulz’s simplicity, the new generation worships him. Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, for example, is a macrocephalic, self-loathing, perennial loser trapped in a boxy wasteland. Dan Clowes’ mix of suburban surrealism and static non-event would be hard to imagine without Schulz’s example. So would Ivan Brunetti’s long sequences of nearly identical panels filled with neurotic blather. And so it goes. Like one of Al Jafee’s Mad Magazine fold-in covers, the barren landscapes of today’s alternative comics need only to be tweaked or rumpled, and suddenly you’re staring at the same darn enormous head.

Schulz’s influence may be pervasive, but it remains uneasy. Gary Trudeau can gush that Peanuts was the “first Beat strip,” but the fact remains that as a counterculture icon, Charles Schulz lacks something, and I don’t just mean a goatee. Bad enough that his work eschews any reference to sex, politics, or graphic violence — the holy trinity of alternative media. That might be forgivable, or, indeed, inspirational (hey, man, wouldn’t it be great to write a comic like Peanuts, but where all the characters have *sexual* hang-ups?). But Schulz’s real sin was that everybody liked Peanuts. And when I say everybody, I’m not talking merely about the working-class, or the ethnically diverse, or the other underprivileged groups that we all love to ostentatiously respect. No, I’m talking about the terminally square: the Republicans, the church-goers, the optimists, and the actuaries. I’m talking about Schulz’s longtime friends Cathy Guisewite and Mort Walker, creators of two of the hokiest comic strips ever unleashed on the unwashed herd.

Peanuts’ universal appeal and studied inoffensiveness made it possible for Snoopy to sell lunch boxes, T-shirts, space flight and life-insurance, and for Schulz to create a multi-media marketing empire. But it had its downside as well. In our society, high art is high art because it entertains the elite; low art is low art because it entertains the rabble. The rabble loved Schulz, which left aesthetes with a problem. Peanuts was indisputably great, but could something be great if nobody disputed it? To appreciate Charles Schulz was to make oneself indistinguishable from the football-obsessed, L.L. Bean-attired, homophobic hordes of Middle America. It was, in other words, a hipster’s worst nightmare. Something had to be done.

Luckily, there are tried-and-true strategies for dealing with a crisis of this sort. As Arnold Bennett stated a century ago, “Even when a first-class author has enjoyed immense success during his lifetime, the majority have never appreciated him so sincerely as they have appreciated second-rate men. He has always been reinforced by the ardour of the passionate few.” The masses may like a genius, but they never like him in the right way. That is left to the graduates of small liberal arts colleges, who, with their deeper understanding, love Shakespeare for the profound philosophy, not for the gratuitous gore; Mark Twain for the deep humanity, not for the slapstick.

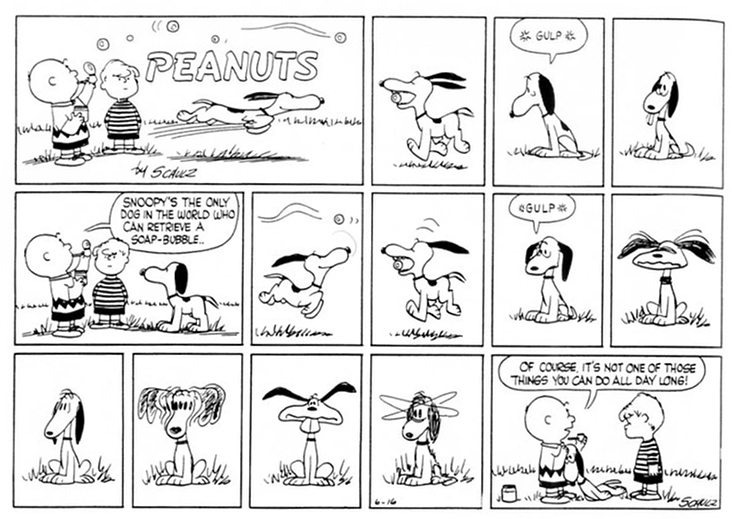

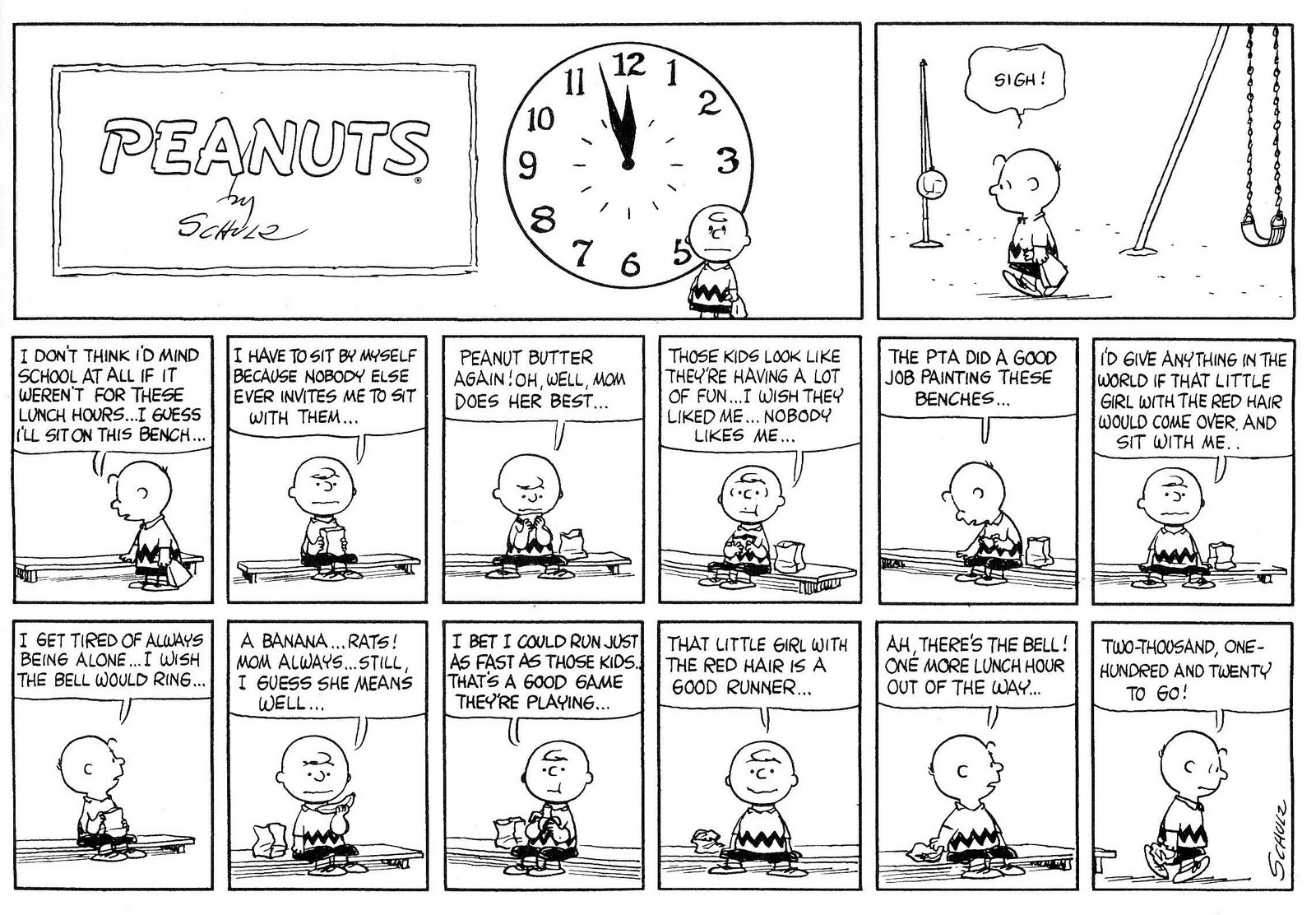

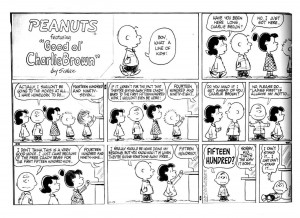

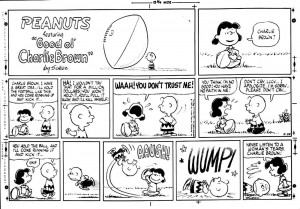

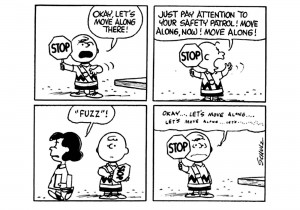

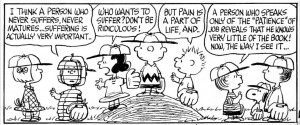

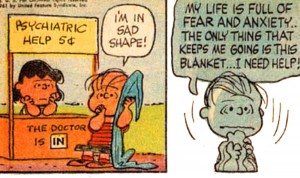

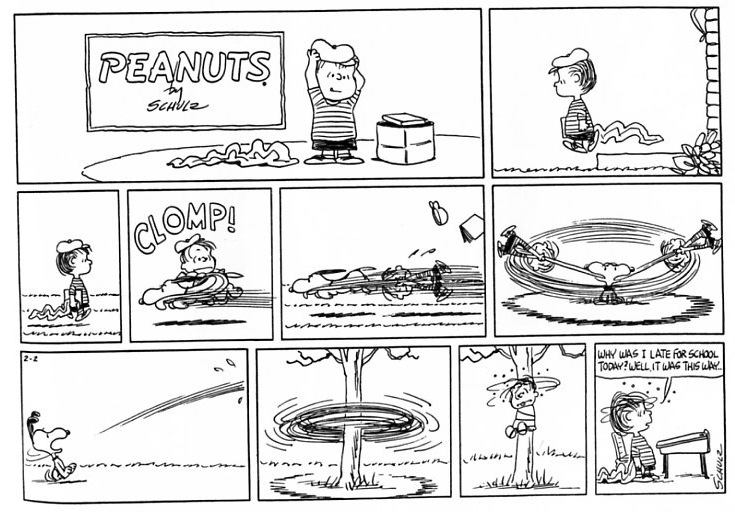

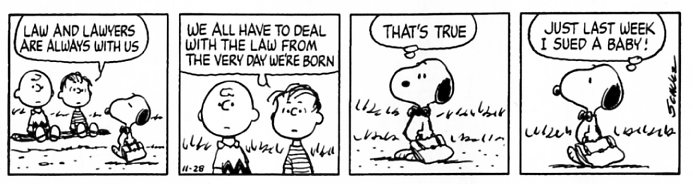

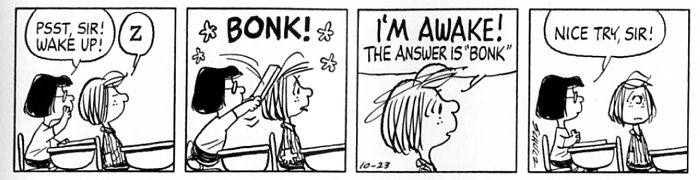

What, then, do most newspaper readers like about Peanuts? Not too difficult a question: it makes them laugh. Schulz wasn’t embarrassed about this; in fact, he pointed out on numerous occasions that it was the main goal of his work. “Cartooning is, after all, drawing funny pictures,” he wrote in 1975’s Peanuts Jubilee, “something a cartoonist should never forget.” Very well, then; if Joe Average loved Peanuts because of its joy, Joe Above-Average would love it because of its despair. The chosen few understood that Schulz was not a genial neighborhood druggist, but a Jeff Tweedyesque mope rocker; they read the strip not to laugh, but to indulge in an orgy of white, suburban, middle-class self-pity. Or as wunderkind designer Chip Kidd claims, Peanuts was “For all of us who ate our school lunches alone, and didn’t have any hope of sitting anywhere near the little red-haired girl and never got any valentines and struck out every single time we were shoved to the plate for Little League….”

And yet. If Schulz was writing for the alienated and the emotionally deep, why did those tortured souls make such a consistent hash when they tried to pay him tribute? Take Kidd’s The Art of Charles M. Schulz, for example. Along with sketches and strips reproduced at every conceivable size, Kidd also included pictures of tschotskes —dolls, magazine covers, promotional materials, and so forth, all bunged together through the miracle of the latest in page-layout software. As Kidd points out, Schulz’s aesthetic was one of minimalism. Why, then, is this celebration of him so cluttered?

If Kidd’s take on Peanuts is mystifyingly wrong-headed, Jeff Brown’s is infuriating. Chris Ware actually compared Jeff Brown to Schulz in a recent issue of Comic Art; both, he argued, were artists who eschewed realism in order to create a world that was “more heartfelt and real.” I don’t doubt that Brown’s description of his own deep sincerity is “real,” at least to him; unfortunately, that does not make it more endearing. In a piece from Kramer’s Ergot Four called “Don’t Look Them In the Eye,” for example, Brown draws himself at work in a Peanuts-like moment, jumping every time the phone rings because he thinks it might be his girlfriend. But, of course, it never is. Also, she won’t have enough sex with him. How poignant.

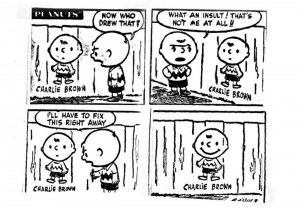

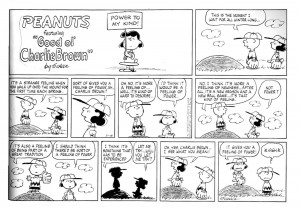

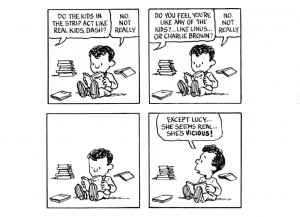

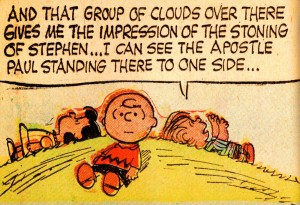

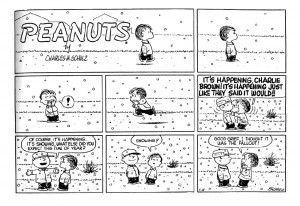

Brown’s work, in fact, is a perfect example of how alternative comics types have take from Schulz one or two stylistic tics while systematically abandoning everything that made Peanuts worth reading. Even a cursory comparison of Jeff Brown’s artwork and Schulz’s demonstrates the enormous gulf between the two. Schulz’s drawings are deliberately simplified; especially in his classic 50s and 60s work, he chooses one or two details carefully to set a scene. What he does choose to draw is rendered idiosyncratically but distinctively — Schroeder’s piano, for instance. And despite the simplicity of the drawing, some of his effects can take your breath away. In the strip I’m looking at right now, Linus and Charlie Brown dissolve into a driving rainstorm, the perspective slowly pulling away from them, until each stands alone, almost completely obscured by the thicket of varied pen strokes. Schulz was charmingly pleased with his ability to create such effects; as he wrote in 1999s Peanuts: A Golden Celebration, “Rain is fun to draw. I pride myself on being able to make nice strokes with the point of a pen….”

Needless to say, this sort of grace is way beyond Jeff Brown. In one scene, Brown is lying in bed with his girlfriend. Crosshatch lines are everywhere; on the walls, on their bodies, on the bed, all running in different directions. We shift from close-up to mid-distance shot to close-up and back to mid-distance, all for no apparent reason. There’s no progression or unity, and the sloppiness is not so much engaging as it is profoundly half-assed. Brown has taken Schulz’s iconic, non-representational style, but left out the reserve and discretion which makes it work. This is brought home most clearly in the middle of “Don’t Look Them In the Eye,” when Brown, more or less at random, includes a blob-like drawing of Snoopy’s friend Woodstock. The best that can be said of this attempt is that Brown’s version, like Schulz’s, looks nothing like a bird.

After the dismal art, the most noticeable thing about Jeff Brown’ work is that every panel features — Jeff Brown. No surprise there; if the super-hero is the fetish of the mainstream, the self is the fetish of the art comic. Perhaps the autobiographical vogue is some sort of overreaction to the shared worlds, house styles, and character ownership of DC and Marvel. Or perhaps it’s simply a solipsistic failure of imagination. In any case, there is little doubt that many in the alternative comics field have difficulty distinguishing between the phrases “personal vision” and “narcissism.”

Unfortunately, as it happens, many of the deities worshipped by the alternative comics crowd — Jack Cole, Winsor McCay, George Herriman, etc., etc. — simply didn’t write confessional narratives (it’s been argued that some of Jack Cole’s work was semi-autobiographical. This is simply too silly to argue about.) Charles Schulz, though, was a different matter. Charlie Brown had, after all, the same first name as his creator; his father, like Schulz’s, was a barber. Schulz even admitted that Charlie Brown’s unrequited affection for the little red-haired girl had its basis in Schulz’s own romantic rejection at the hands of a red-headed woman named Donna Mae Johnson.

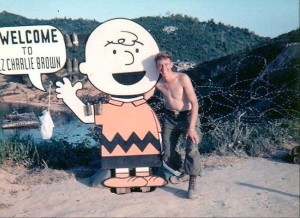

Commentators eager to establish Schulz’s high-art credentials have been quick to pick up on these hints. In his Afterword to the first volume of the Complete Peanuts, for example, David Michaelis compares Schulz to Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and — oddly enough — Henry James. The heart of the essay, though, is the insistence that Peanuts was based on Schulz’s own “lifelong sense of alienation, insecurity, and inferiority.” In a recent Chicago Reader article, Ben Schwartz makes pretty much the same point. Both Schwartz and Michaelis dwell lovingly on the most painful aspects of Schulz’s biography — his troubles in school, his mother’s early death, his wartime service. Schulz is great, in other words, because he has suffered: because of who he is as much as because of what he did.

Schulz is credited, then, with using the comic strip to reveal his own tortured soul. In the fifties, when Peanuts started, the triumphant flourishing of psychic wounds was as common as Bildungsromans in literary fiction. On the funnies page, though, it was a novelty. No more; if it’s whining, insular self-reference you want, art comics are now the go-to genre. Cartoonists today routinely write entire strips devoted to the great suffering one experiences as a cartoonist. When Dan Clowes did a cover for the Comics Journal a while back, he filled it with ruminations on how hard it was to create a cover for the Comics Journal. In Maus, Art Spiegelman wrote about how hard it was to write Maus. Ivan Brunetti and Chris Ware have both written comics about the terrible, existential pain of writing comics. And both Brunetti and Ware have justified them with the same quote from none other than Charles Schulz: “Cartooning will destroy you. It will break your heart.”

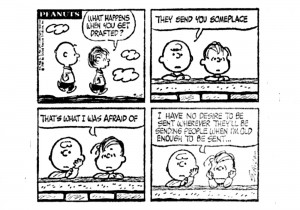

As those words indicate, Schulz did have something of a chip on his shoulder about the low status of comics writers. He also felt that writing the strip year after year, and coming up with ideas day after day, made cartooning “very demanding.” For the most part, though, he kept his problems in perspective. “Every profession and every type of work has its difficulties,” he noted, and added, “I don’t want anyone to think that what I do is that much work..” Whatever his frustrations, therefore, the strip never descended to bathetic self-dramatization. Charlie Brown whined about sports, or camp, or his dog, or the little red-haired girl. But he never whined about the spiritual trauma of being a rich and famous cartoonist.

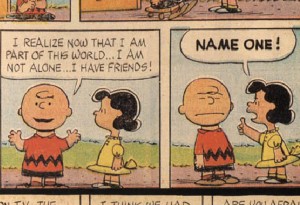

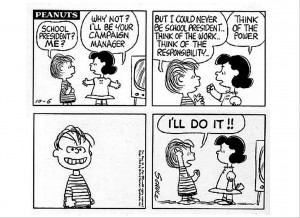

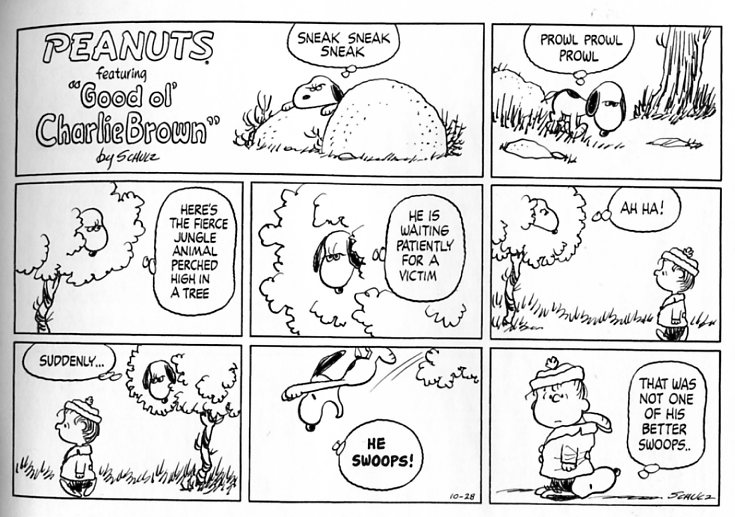

And why should he? Charlie Brown was never a stand-in for Charles Schulz. Indeed, in A Golden Celebration, Schulz argues that Charlie Brown is the least realistic of the Peanuts cast. “He’s certainly the only character who’s all one thing,” Schulz points out. “He’s a caricature.” Obviously, Charlie Brown’s hyperbolic suffering is an aspect of Schulz’s psyche. But so are Schroeder’s virtuosity, and Sally’s indignation, and Linus’ spirituality, and Snoopy’s preposterously fertile imagination. So is Lucy, who comes, Schulz says, “from that part of me that’s capable of saying mean and sarcastic things….” Sure, Schulz is the kid who always misses the football. But he’s also the kid who always pulls it away.

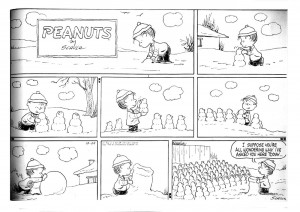

So, yes, Charlie Brown was important to Peanuts. But he didn’t define the strip and he didn’t define Schulz. This can be a painful realization for those who value earnestness in their art. Critic Christopher Caldwell, for example, wrote an essay for the New York Press in which he took a bold stand against Snoopy’s happy dance and complained that in its later years Peanuts had moved from “heartbreaking” to “sentimentalism.” It’s an interesting thesis, but one that ignores an important point: Schulz always mixed a fair bit of sweet with his bitter. One Sunday strip in the 60s, for example, showed us a crabby Lucy wandering around the house and bitching. “Count your blessings,” Linus advises, which only prompts another tirade. “What do I have to be thankful for?” she demands. “Well for one thing,” Linus replies, “You have a little brother who loves you….” Lucy pauses for a panel…and then clutches Linus and breaks into tears. “Every now and then I say the right thing,” Linus muses as he hugs her back.

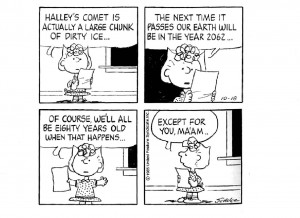

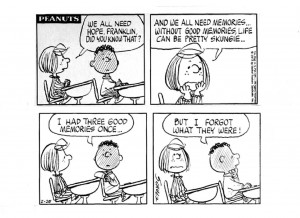

I doubt Caldwell or his ilk would like that strip very much I doubt they’d like the series in the 90s where Charlie Brown gets a girlfriend either. Or the utterly bizarre Sunday comic where the punchline is Snoopy looking at a golf ball in a water trap and thinking, “That doesn’t look like Moses.” Or the one which consists entirely of Sally discussing how her eye patch will cure her amblyopia (there is no discernable punchline.). Or the one where Charlie Brown explains to a deeply grateful Linus that the cure for disillusionment is a chocolate cream and a friendly pat on the back. These strips aren’t grim; they aren’t existential. Presumably, they aren’t true to Peanuts tragic essence. But the essence of the strip was never Schulz’s sadness. It was his professionalism, his inventiveness, and, above all, his sense of humor. After all, any idiot can tell you that life sucks. When they do, though, I wish they wouldn’t pretend they got the insight from poor ol’ Charlie Brown.