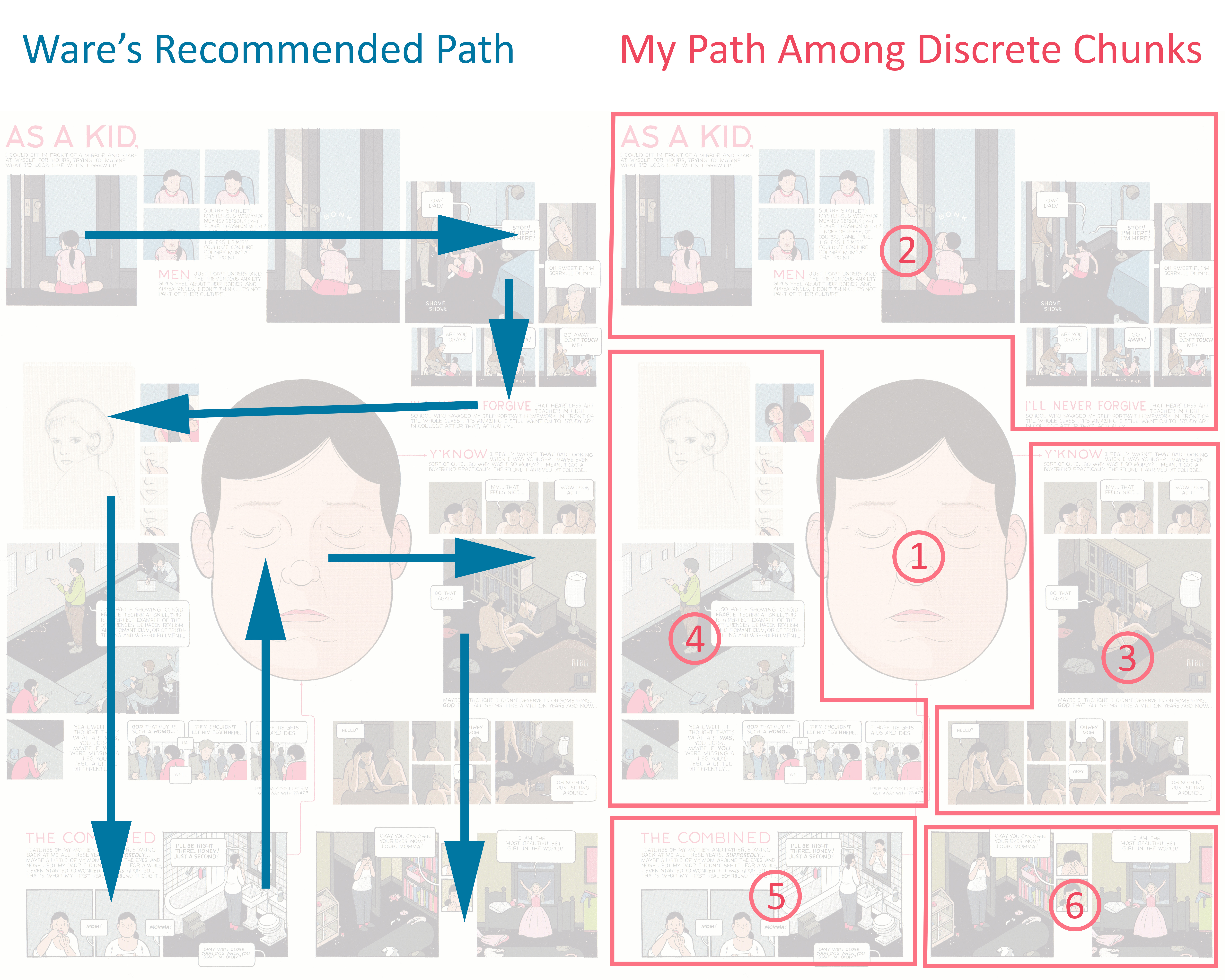

Following tardily on the heels of this month’s onslaught of architecture-based posts, welcome to a belated examination of the ways in which we read comics and architectural working drawings. Based on the merits of a comment I made on Alex Buchet’s first “Draw Buildings, Build Drawings” article, Noah invited me to elaborate on the topic in the form of a guest post. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for some time, but not necessarily something that has much practical value for anyone looking to analyze either comics or architecture.

As an architect and cartoonist, I can’t help but notice many similarities between comics and architectural construction documents. Superficially, the pages of both tend to convey information in similar ways: drawings of simplified pictograms are ordered into grids of panels, often in conjunction with text and an elaborate system of symbols and line weights. But is there a more fundamental way that we can understand each?

In this post, I will look at how we read both architectural drawings and comics, based on my own understanding of how each works. I’m going to apologise in advance for my limited knowledge of comics theory; I am going to base most of that segment on my own observations about how they function. Feel free to jump on me in the comments if anything doesn’t ring true.

A caveat: I will not be discussing architectural illustration/renderings, drawings meant for public consumption, publication in architectural journals, or intended for competitions. Rather, I will be taking a rather narrow look at architectural working drawings, and the commonalities and dissimilarities they share with comics. I will also not be considering single-panel gag strips, as it is really the act of reading a page of comics that I am interested in for the purposes of this post.

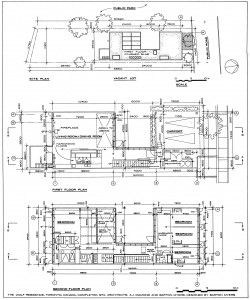

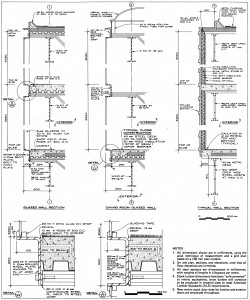

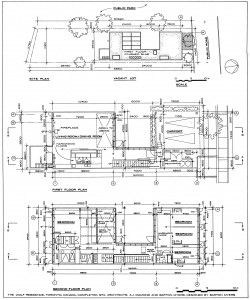

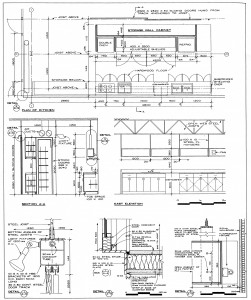

Site Plan and Floor Plans: The Wolf Residence, by Barton Myers (Note that these architectural sheets are not from a construction set; rather, they are the metric system instructional drawings from Architectural Graphic Standards, and thus differ slightly from contract documents)

How We Read Architectural Drawings.

Architectural drawings are, at their essence, a series of iconic pictograms organized in such a way as to allow a third party to construct a building based on the designer’s concept. These drawings are typically depicted as “cuts” through the imaginary building, both horizontal (plans) and vertical (sections) – though some drawings, including elevations and roof plans, are not.

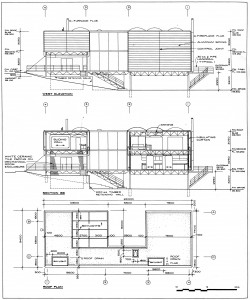

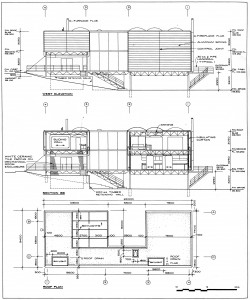

Elevation, Section and Plan from Myers’ Wolf Residence

Architectural working drawings are generally organized by scale, smallest to largest. From a plan point of view, this usually entails starting with the site plan, then the building plan, plan enlargements, and plan details (this ordering system also applies to sections, as well). The benefit of this approach is that it allows the designer to identify important building elements that are focused on in more detail with each subsequent enlargement. It is also possible to indicate elevations or sectional details on plans, and vice versa. This is accomplished with a variety of identification tags and bubbles, conventional symbols that guide the reader to the appropriate page. While this method of navigation may seem difficult at first, it is possible for the diligent layperson to parse its meaning and “read” an architectural set.

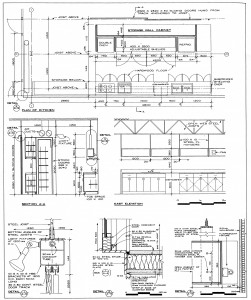

Plan Enlargements, Interior Elevations, and Details from the Wolf Residence

These pages are laid out in a grid of discreet drawings, each marked by an identification tag that marks the destination from the tags on the building-scale sheets. The smaller the scale (ie. the smaller the building appears on the page), the more of the sheet is taken up by the drawing; the converse is true of a large-scale detail. Thus a site plan usually appears by itself, while details can be twenty-four or more to a page. A page of details is a holistic field of drawings, with no one frame given more weight than any other; this allows the casual observer to jump in at any point and understand that part of the building, while simultaneously denying them the opportunity to construct a narrative from the panels. Daniel Worden made an interesting point in his essay “On Modernism’s Ruins: The Architecture of ‘Building Stories’ and Lost Buildings” (from the book The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking), when he talked about the “dialectical relation… between the fragment and the whole, the panel and the page, the page and the text…”. He was writing about Ware’s comics in “Building Stories”, but he could just as easily been discussing the tension between the sheet of details and the building as a whole.

Architectural details from the Wolf Residence

Unlike comics, architectural drawings cannot function as illustrations alone. Text is always required on these sheets, though it is necessarily descriptive, not narrative in nature. These notes call out materials and processes (ie. construction sequencing), generally accompanied by arrows indicating which elements are being described.

How We Read Comics

Comics are, at their essence, a series of composed iconic pictograms organized in such a way as to allow a third party to mentally construct a narrative. It is the purposeful sequential arrangement of these drawings that allows us, as readers, to decipher the cartoonist’s intent.

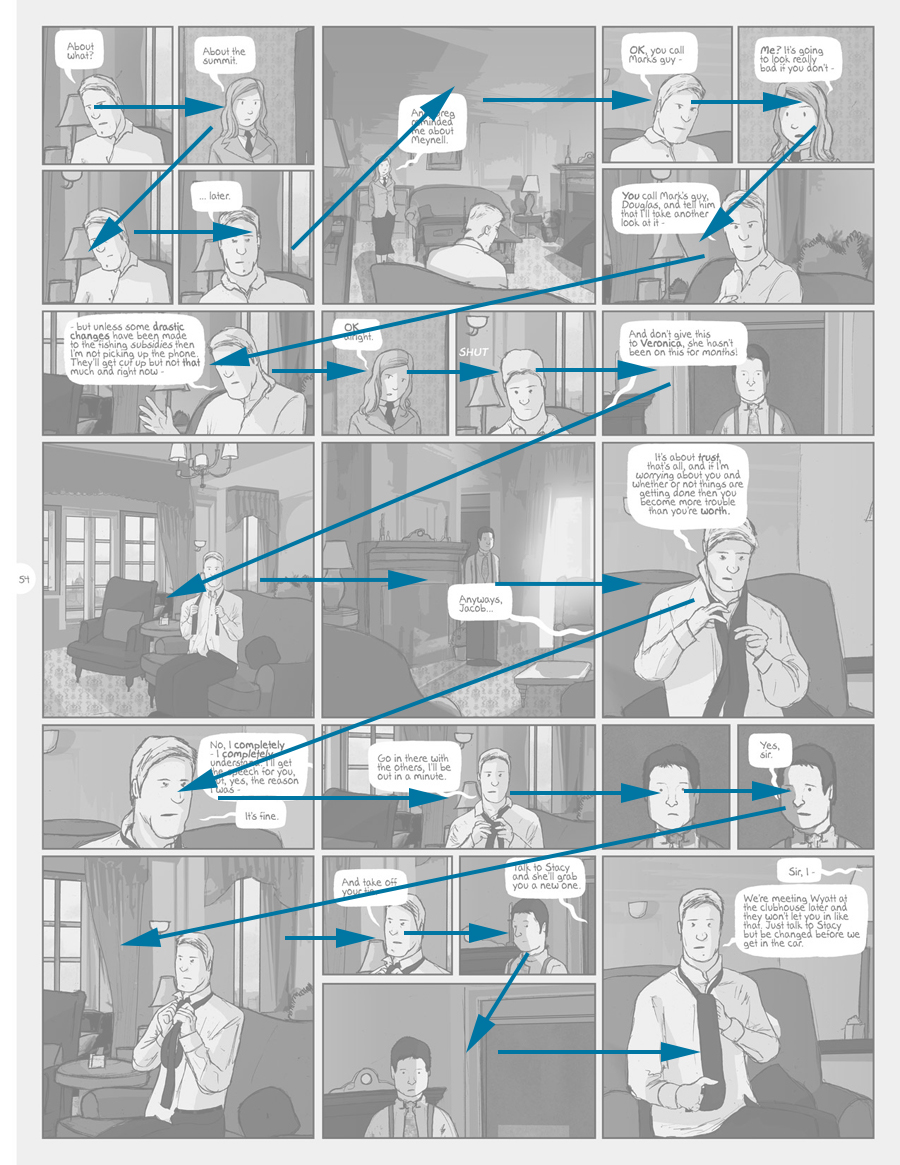

As mentioned earlier, comics share some general organizational principles with architectural drawings: in particular, the grid. A page of comics typically adheres to a strict grid of individual drawings bounded by panel borders and separated by gutters (negative space between the frames). Despite this superficial similarity to architectural drawings, the “rules” of cartooning are much less hard and fast than those of the construction documents. The direction of reading and the shape of panels need not be consistent as long as the narrative thrust is clear to the reader.

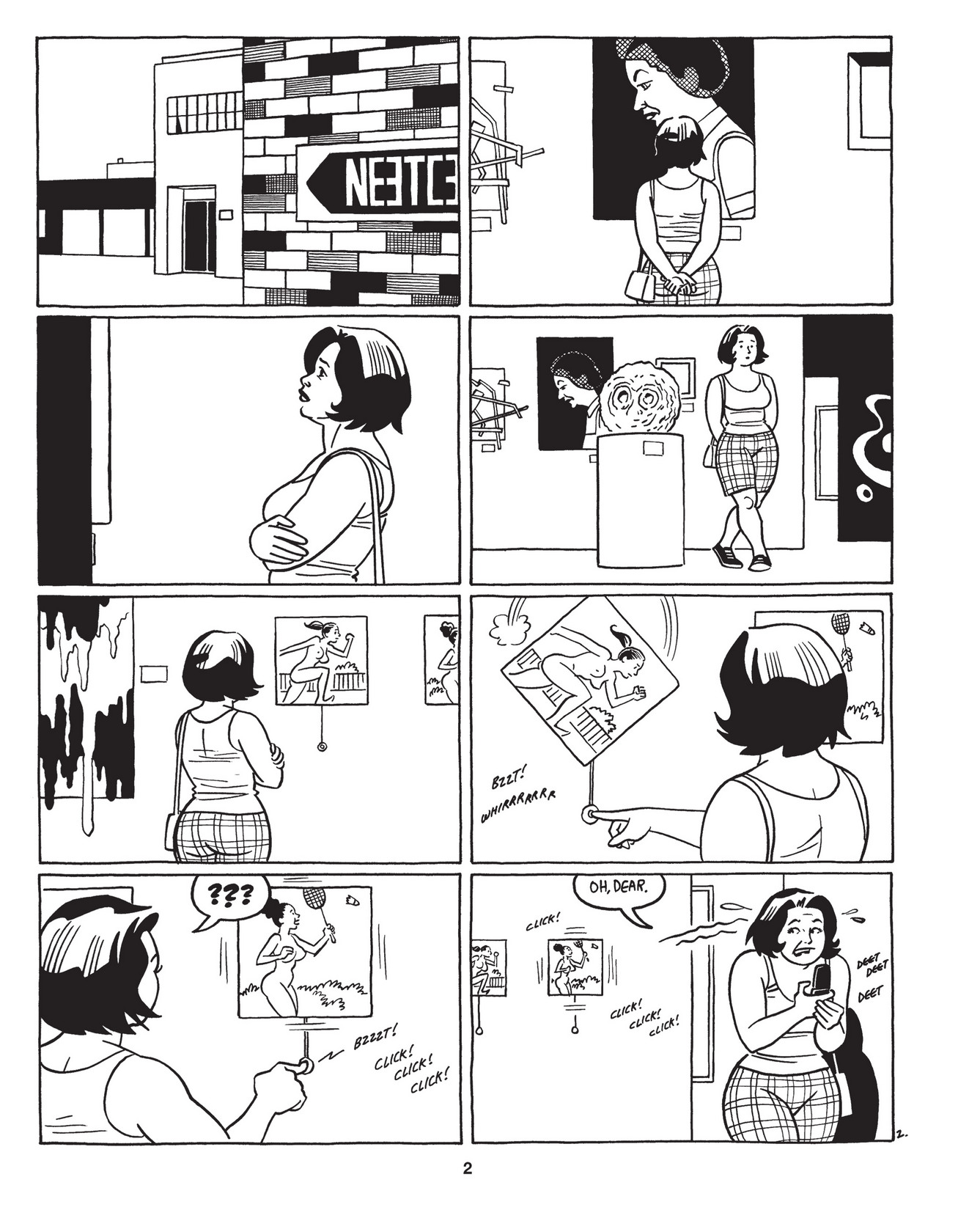

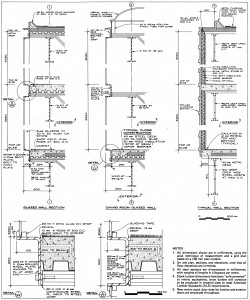

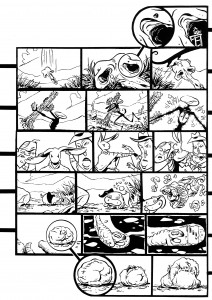

Maggots, by Brian Chippendale

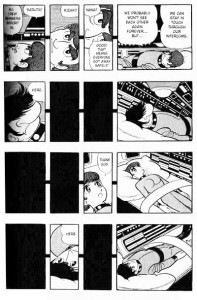

For example, Brian Chippendale often uses a regular method of laying out panels so that we read “like a snake” back and forth down one page and up the next; Osamu Tezuka has been known to allow readers to move their eyes either horizontally or vertically, with both directions achieving the desired narrative effect.

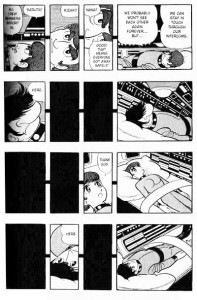

Osamu Tezuka’s “Space”, from Phoenix

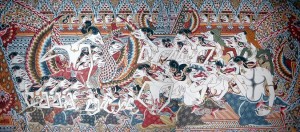

In both cases, a patient reader can comprehend the writer’s intent and follow the prescribed narrative. On the other hand, scroll-like comics without borders (or comic-like scrolls), like the Bayeux Tapestry or portions of Dash Shaw’s Body World, direct the eye in such a way as to allow even the most visually unsophisticated reader to comprehend the author’s intent.

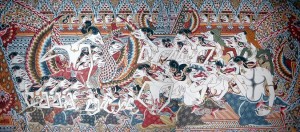

Wayang Beber: Indonesian narrative scrolls that function like comics

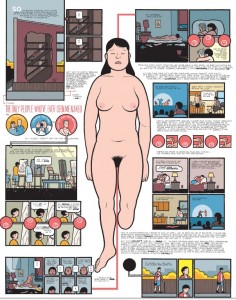

Body World, by Dash Shaw

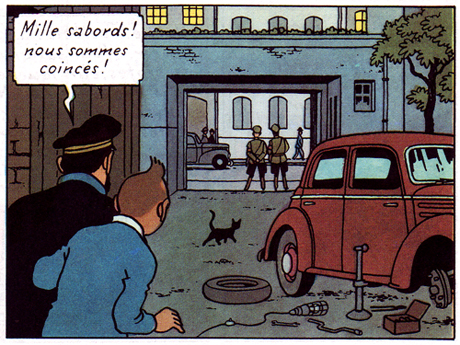

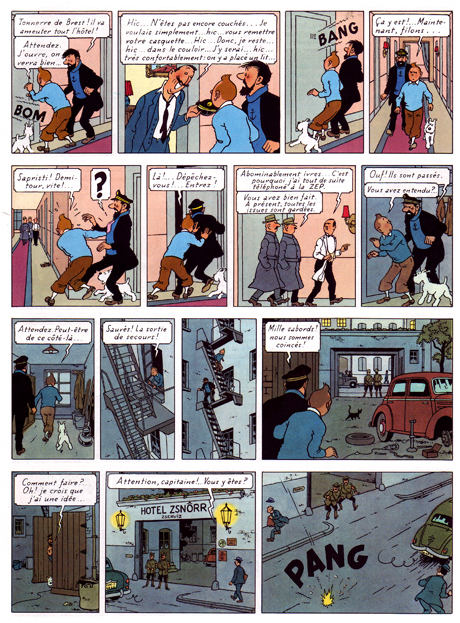

But how do we know how to read a comic? We seem to inherently want to read panel-to-panel in the same way we read prose: left to right, top to bottom. However, even the most basic arrangement of panels does not always follow this pattern, with unusual arrangements of tall or wide frames that seem to disrupt the eye’s flow. Navigating a comics page is a learned skill, one that is arrived at through trial and error (often as a child, desperately trying to decipher a page of Bone or Tintin).

And how are we able to interpret the pictograms on the page: person, dog, house, movement, distress? Perhaps this too stems from our childhoods, and our own artistic inability to accurately depict the world around us; with our unskilled hands, we can only illustrate an over-simplification of what we see with our eyes. This is not dissimilar to the purposeful simplification of reality as filtered through a cartoonist’s pen, which may explain why so many of us are drawn to comics as children. Architectural drawings are not as intuitively understood. I would hazard to say that it is these very comics-decoding skills that would enable the casual observer to decipher a set of construction documents.

As has been mentioned previously, one of the primary features of the comics page is a bias towards narrative momentum. This generally involves the perception of time by the reader. This is manifestly different than an architectural set, where time is not a consideration in the drawings themselves. Rather, this points to the fundamental difference between these two modes of visual communication: the architectural set is a means to an end, while a comic is the final product itself. Narrative in architecture does not come into play until the drawings are read, understood, and constructed; buildings are meant to be experienced in four dimensions, not two-dimensionally on paper.

So all of this begs the question – why bring this up at all if these two art forms are so fundamentally different? How does architecture – on paper – relate to comics? Is there an approach to reading architectural drawings that can be applied to comics?

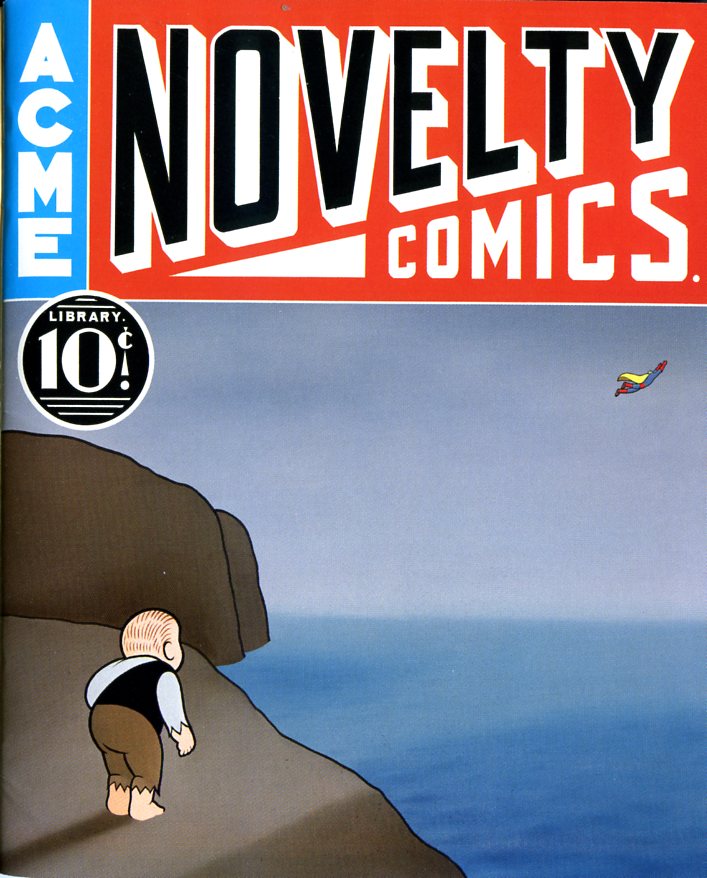

There are endless examples of similarities between comics and architectural renderings, most of which have been touched on in Alex’s previous posts (François Shuiten, Jiro Taniguchi, Hergé, etc.). However, I find that these illustrations stray somewhat from the practice of architecture as discussed in this essay. Architectural renderings are as much architecture as a cover illustration is a comic book; both are meant to grab the public’s attention and “sell” the content (either a comic or a building, as the case may be).

Rabbit Head, by Rebecca Dart

There are examples of cartoonists who are keen to play with the formal aspects of comics in such a way that their work begins to resemble modes of reading architectural drawings. Rebecca Dart’s Rabbit Head is perhaps a good starting place, as it makes use of several of the conventions mentioned above. Rabbit Head is a relatively standard comic, but one with a peculiar method of reading: a single narrative strand gradually splits into multiple narrative paths that are meant to be read at the same time to create a larger web of story. From the beginning, it is apparent to the reader how we are to follow the multiple plots; a system of symbols and tags clearly points our eyes to the simultaneous narratives. This system is extraordinarily similar to architectural navigational symbols, but it is perhaps more easily understood.

Like an architectural set, each of these narrative branches tends to literally increase in scale as it breaks from the central story. The further the split is from the primary narrative, the more the panels zoom in. This is not dissimilar from the progression from plan to detail in architectural drawings. There is even a map at the back of the book that provides an overall view of the action, and points out key narrative locations, much like an architectural “key plan”.

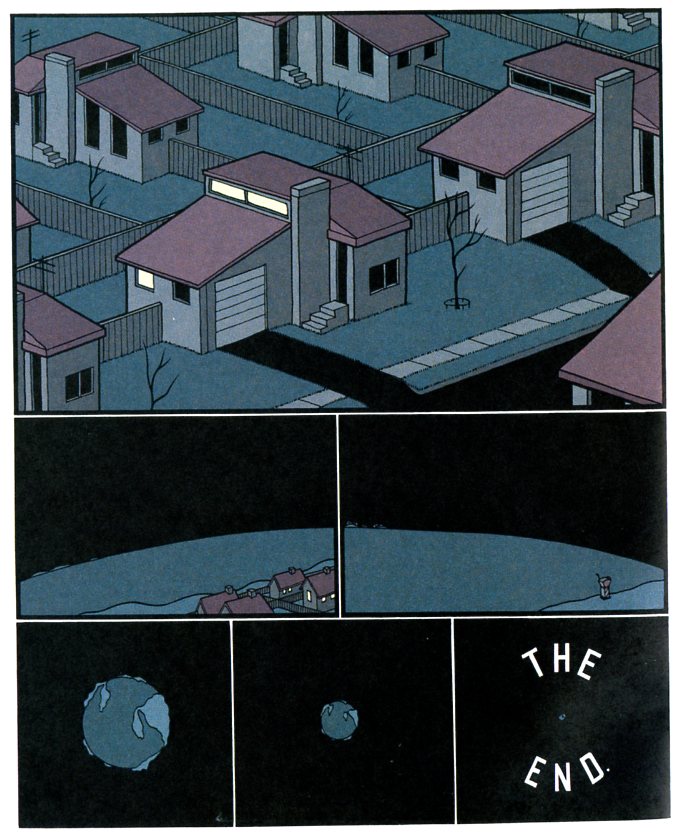

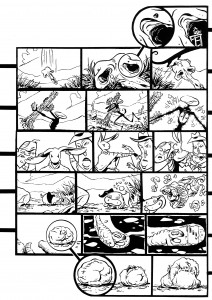

Page 9 of Morlac, by Leif Tande

Morlac, by Leif Tande, follows a similar narrative conceit to Rabbit Head. It is a “Choose Your Own Adventure” of sorts, one that begins with a single panel per page. As the main character is faced with directional choices, so to is the reader, and the narrative splits up, down, left and right. As a reader, the inclination is to follow only a single strand of narrative, but it quickly becomes evident that this is not how Morlac is intended to be read; the character begins to interact with the other “selves” on the page. The pages ebb and flow, apparently populated semi-randomly with a holistic field of discreet panels as the main character comes and goes. The effect is similar to opening an architectural set to a page of details and trying to discern the overall building from those few drawings. The “narrative” in Morlac is the equivalent of the “architecture” in a set of construction documents.

Page 25 of Morlac

There are other comics that explore similar territory (including some by Jason Shiga and Lewis Trondheim, among others), but I feel that none are able to capture this “architectural essence” as well as Tande and Dart.

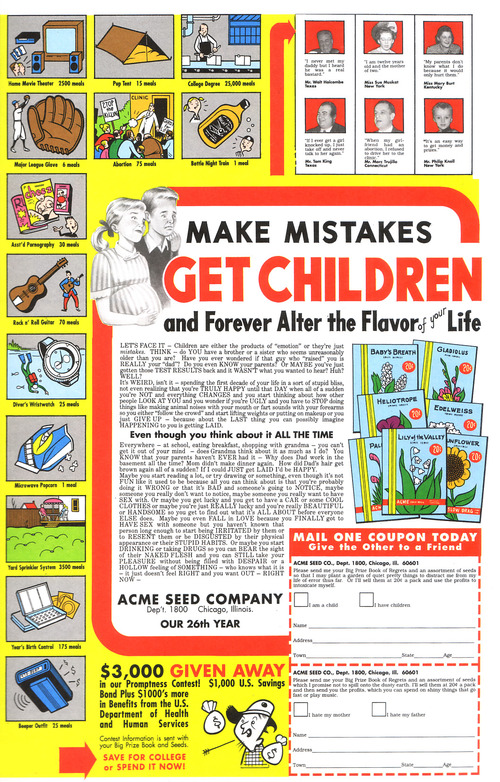

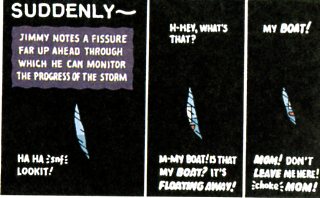

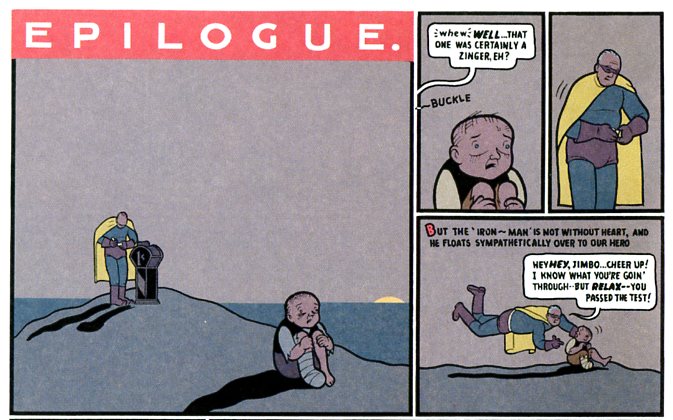

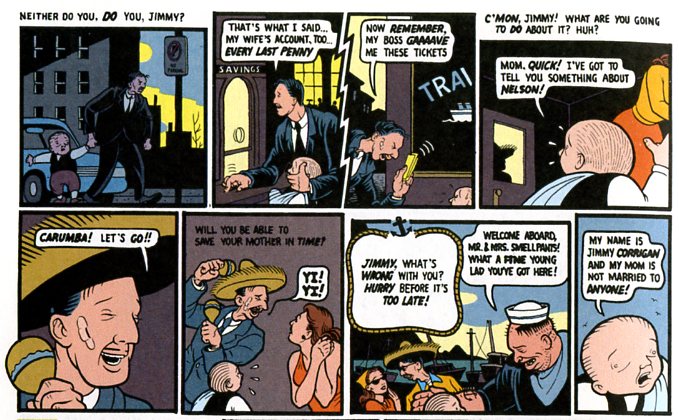

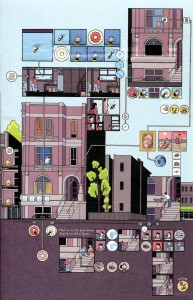

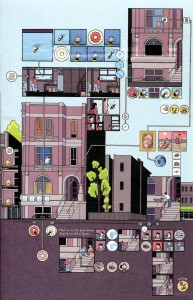

Chris Ware’s “Big Tex”

No discussion of architectural representation and comics is complete without Chris Ware. Not only is he an adept draftsman, but he seems to grasp certain methods of architectural representation that have not really been exploited fully by anyone else. Take, for example, a “Big Tex” strip from the Acme Novelty Joke Book: the page as a whole illustrates a finite amount of space, which is subdivided into individual panels in order to depict a larger scene and drive a narrative. Architectural details are often laid out this way on a page, so the eye can travel around the perimeter of the building, for example, or down a façade in a way that the mind can easily comprehend. Ware exploits the narrative flow across the page and he composes the panels in such a way as to guide the reader across the page and back again, not always in the same direction. He also takes advantage of this unusual flow by running the strip back in time from top to bottom, following both Tex and the tree from middle age back into their respective youths. This is certainly an interesting and exciting approach to comics, echoing closely methods of laying out architectural details on a sheet. Though I cannot say with any certainty that Ware was influenced by architectural drawings, I feel that his chosen mode of representation in this instance is close enough to warrant a mention.

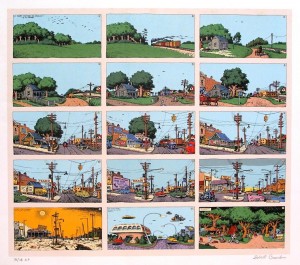

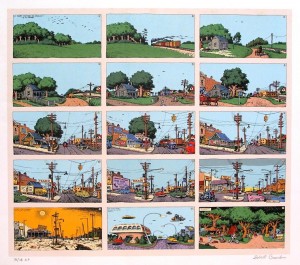

“Gasoline Alley” 1934 Sunday page, by Frank King

Innovative as this page is, that’s not to say Ware’s work does not have precedent. Perhaps the most direct influence on this particular “Big Tex” page are the many similar pages from Frank King’s “Gasoline Alley”. King loved to lay out pages as a field of panels that together created an overall image, often returning to the same spot Sunday after Sunday to explore the building of a house over time, for example. However, King was as not as concerned with narrative experimentation as he was with pushing certain formal boundaries.

“A Short History of America”, by Robert Crumb

It wasn’t until almost half a century later that the extra layer of chronology was pushed into King’s formula; Robert Crumb built on King’s work with his one-page Short History of America, and Richard McGuire cracked it wide open with the brilliant and challenging Here.

“Here”, by Richard McGuire

Ware synthesized each of these elements and produced an intriguing post-modern comic that is entirely his own voice, influences notwithstanding and, in fact, celebrated (this will probably be the only time I’ll ever compare him to Quentin Tarantino, but I think the comparison is apt in this case).

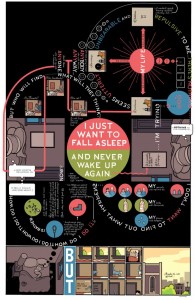

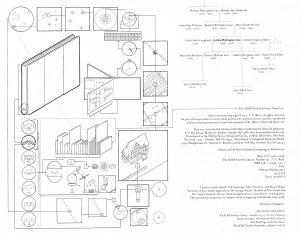

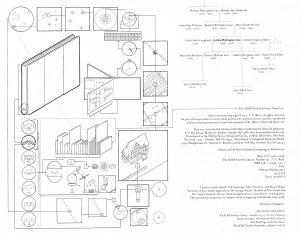

Chris Ware’s endpaper diagram for “Lint” (ACME Novelty Library No. 20)

Ware also has a penchant for diagrams that function on the same level as architectural drawings. They can communicate a large amount of information that, if it was told as part of the narrative, would interrupt the flow of the story; some are even tangential to the narrative entirely. Ware often inserts these diagrams into and around the narrative in the least disruptive way possible; he tends to save the most elaborate ones for covers, endpapers, or frontispieces, while working the simpler ones into the body of the comic. Like an architect, he uses a standard set of symbols to signify a complex set of relationships in the clearest manner possible. Some would say that this is a masturbatory self-indulgence on Ware’s part, but I find his diagrams both edifying and entertaining. Anyone interested in exploring this topic further (from an information design point of view, rather than an architectural one) should have a look at Isaac Cates’ essay “Comics and the Grammar of Diagrams”, from the book The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking.

Endpaper diagram from Ware’s “Building Stories” (ACME Novelty Library No. 16)

Now, having examined a few examples of existing comics, what would my ideal architectural meta-comic look like? It would not necessarily be an abstract or non-linear piece; as I’ve stated previously, I feel that in one sense, the narrative (or simply a perceived temporal momentum) is to comics as the constructed building is to architectural drawings. To me, the perfect “architectural” comic would read something like Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Let’s assume for a moment that it would be exactly like Invisible Cities: a literal cartoon adaptation. The book is structured around a central (sparse) narrative involving Marco Polo describing cities he has visited at the court of Kublai Kahn. The majority of the novel is taken up by these stories, and the Kahn slowly comes to realize that each tale is describing a different aspect of Venice, Marco Polo’s home. Kublai Kahn listens to Polo, not understanding yet somehow comprehending; a good portion of the book passes before Marco Polo learns to speak Mongolian. An adaptation of Invisible Cities might fare well as a wordless comic, benefiting from the extensive use of symbols and diagrams. To me, Invisible Cities is ideally suited to an “architectural comics” experiment such as those I have outlined in this post. The overarching narrative functions like a building’s plans, with each subsequent tale like another detail describing the whole. The sequence of stories could be entered randomly and understood individually, though they would not allow the reader to perceive the whole without approaching the narrative a particular way (chronologically, in this case). The descriptive nature of the stories within lend themselves naturally to illustration; with a little planning (and a whole lot of drawing), they could be arranged in such a way that they could function like an architectural drawing set. If anyone is up to the challenge, I will gladly read your comics interpretation of Invisible Cities.

Aaron Costain is an architect and cartoonist who lives and works in Toronto.