A response to Christa Blackmon‘s “How The Walking Dead became the Realest Show on Television.”

“American popular media is in dire need of stories that help us build empathy with the rest of the world, and science fiction dramas like The Walking Dead, that feature realistic storylines and a diverse cast and crew, can help fill that void.”

– Christa Blackmon

The idea that one should have empathy with displaced persons all over world is perhaps incontrovertible. It seems hardly questionable that we should do our best to help the hungry, poor, and afflicted of the world to the best of our abilities.

In her article on the positive ethical dimensions of The Walking Dead (TWD), Christa Blackmon enumerates a long list of worthy projects connected directly or thematically to TWD TV show. These include Sarah Wayne Callies’ work with the International Rescue Committee, Danai Guirira’s co-founding of Almasi Collaborative Arts and Hawa Abdi’s transformation of her family farm into a hospital camp for refugees in Somalia. All this leads up to her call for science fiction dramas to continue the good work of moulding the ethics and inclinations of their viewers and readers.

This assumes of course that these vehicles (ranging from Star Trek to Battlestar Galatica) are unproblematic in their politics and ethical considerations.

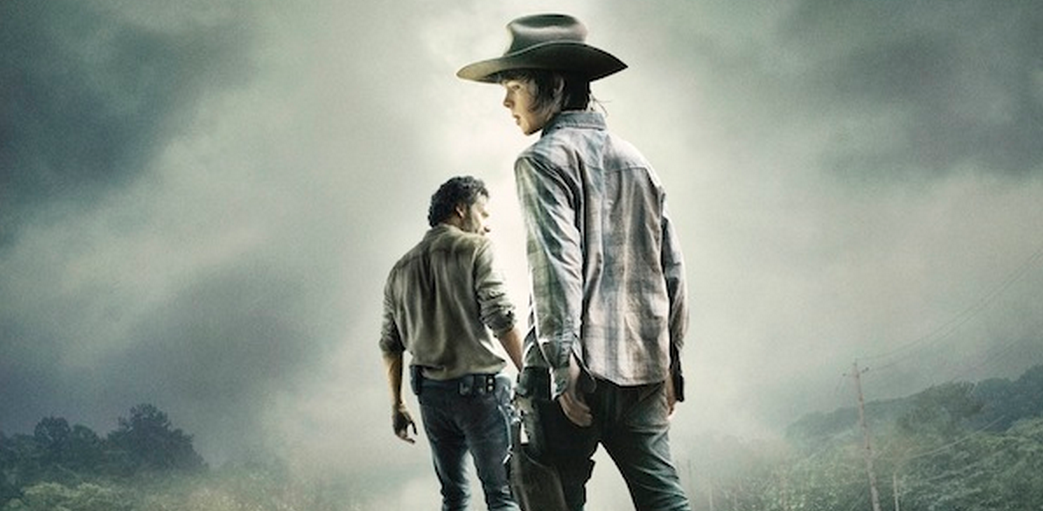

I have barely read more than 20 pages of The Walking Dead comic but the TV series seems less about virtuous behavior then moral dilemmas—preaching has rarely made for good entertainment or cable subscriptions. Having said this, for a series about death and dying, The Walking Dead does seem to have a rather optimistic and comforting attitude towards life. The creators of the TV series in particular make a point of culling only those characters of secondary interest to the viewers. They in turn feel assured that both Rick Grimes and fan-favorite Daryl Dixon (among others) are unlikely to be eaten anytime soon providing they like their contracts; a fact which has been made fun of by no less august an institution than TV.com.

DARYL DIXON

Role: Rebel and fan favorite

Strengths: Endless supply of magical crossbow bolts; badass f*cking attitude; alliterative name; the unwavering love of millions

Weaknesses: Ha! Come on, Daryl doesn’t have any weaknesses

Chances of surviving on his own: Pretty good, I’d say! And with millions of fans ready to boycott the series if he ever dies, even better than that. But let’s say The Walking Dead really wanted to be shocking; wouldn’t the show at least consider the possibility of *gets murdered by Dixon’s Vixens*

Life expectancy: A long, long time. Did Sawyer die? Did Han Solo die?

BETH GREENE

Role: Farmer’s daughter

Strengths: She can sing; emotionally empty after caring for too long, so she won’t be held back by tough decisions

Weaknesses: Might be suicidal; fragile as a dry leaf

Chances of surviving on her own: Oh come on, they can’t kill Beth! Don’t you DARE kill Beth!

Life expectancy: They’re gonna kill Beth. She’s done this season or the next.

So The Walking Dead—optimistic and humanistic. Does this sound about right?

Contrary to popular belief, TWD TV series frequently offers up a world of conservative values and black and white morality.

Our heroes may be difficult, morose and frequently irritating but they are generally “good.” Their enemies have been murderous stragglers on the highways of the apocalypse, a psychopathic despot ruling over a town of survivors and, at the close of the last season, gentle human herding cannibals. I think it would be quite easy for most viewers to choose between these factions in the event our world becomes overrun by the undead (this presumes you’re good too, dear reader).

And this is the illusion of much popular fiction (science fiction or otherwise)—that it is not only easy to choose sides but that our point of view (our side) is always the correct one for all its faults.

[Spoilers Ahead]

“The Grove” (S04E14) will probably be cited as evidence to the contrary. It is, of course, noted for breaking the taboo on child murder: the hapless killing of her own sister by Lizzie Samuels and the capital (preventative) punishment instituted by her caretaker, Carol Peletier.

In her short commentary on this episode, Blackmon suggests that “we can take solace in the fact that children in our world do not have to suffer alone and psycho-social services can be available.” But that is not the only lesson we can take from what many consider the best episode of Season 4 of The Walking Dead.

Lizzie Samuels kills her sister as a result of some kind of psychopathy (certainly a serious delusion) where she considers the undead as bounteous as her fellow humans. It is never in question (to the viewers) that the derangement is permanent since she had threatened to stifle and zombify a helpless baby just a few episodes before.

Lizzie’s caretaker, Carol, has been rewritten over the course of Season 4 and transformed into a hard-nosed survivalist who is willing to do whatever it takes to ensure the continuity of the group. She has demonstrated that she firmly believes in a policy of pre-emption. Earlier in season 4, she kills a pair of plague victims because they stood little chance of surviving their affliction and had instead become a source of contamination. She also takes it upon herself to kill (through tears I should add) Lizzie, a zombie religious zealot who threatens to decimate all those around her. Her actions are sanctioned by Tyreese, the lover of one of the plague victims who she killed. Her crime of murder is forgiven but not forgotten in light of the crushing anguish her soul has to withstand as a result of her deeds. The logic at play here is that it’s “what’s in your heart that matters most” and that nothing would have saved Tyreese’s plague-stricken lover one way or another—the narrative of TWD has made that clear.

Viewers of the The Walking Dead TV series are likely to say that Carol isn’t supposed to be nice but it is safe to say that we’ve seen all this before in assorted other entertainments—Carol is the Jack Bauer of the zombie apocalypse.

Bauer is renowned for his effective albeit fictional physical examinations of the gnats feasting on the hide of American civilization. He has been reported to be a favourite among the torture elite. That Bauer’s success in this arena appear to have been repudiated by real life experience is of little consequence.

For her part, Carol performs the unpleasant but necessary work which is a counterpart to maintaining the fruits of civilization (so that you and I don’t have to). How much more poignant would it have been if Carol’s action had not only been pointless (as it was) but also premature and harmful; if a cure had stepped into the plague-stricken prison within hours of her murderous activities; or if Lizzie had simply taken some berries causing her to hallucinate temporarily (this could still be the case). As it happens, Carol’s actions are horrifying, difficult but, in the final analysis, understandable. She is the Madeline Albright of Zombieland; the former United States Secretary of State who when confronted by Lesley Stahl on the question of the half million children who died as a result of U.S. sanctions against Iraq advised her interlocutor that:

“I think this is a very hard choice but the price – we think the price is worth it.”

Carol Peletier could not have put it better herself; the main difference being that Carol offers her own life to Tyrese in “compensation” for her sins; in this way identifying with the monstrous child she dispatched earlier. In other words, she sees herself as a danger to mankind.

Her actions in this instance suggest the buoyant perspective TWD has on human nature, for how often do we actually see the child murderers of our own times even offering to go to court?

Who is Lizzie Samuels but one of those faceless, helpless but contaminated children who need to be sacrificed for the greater good of civilization itself? The article at The New York Times linked to by Blackmon concerning Dr.Hawa Abdi is exemplary in explaining the difference between the good children and the contaminated ones.

Nicholas D. Kristof’s opening gambit in that article reads as follow:

“What’s the ugliest side of Islam? Maybe it’s the Somali Muslim militias that engage in atrocities like the execution of a 13-year-old girl named Aisha Ibrahim. Three men raped Aisha, and when she reported the crime she was charged with illicit sex, half-buried in the ground before a crowd of 1,000 and then stoned to death.”

He ends in praise of Dr. Hawa having explained the difference over the course of his article:

“What a woman! And what a Muslim! It’s because of people like her that sweeping denunciations of Islam, or the “Muslim hearings” planned in Congress, rile me — and seem profoundly misguided.”

To some there will seem little amiss in this approach—a perfectly sensible way to formulate an article on a “good” Muslim. But imagine, for a moment, if all articles on the laudatory nature of American foreign policy read like this:

“The United States has killed hundreds of thousands of people in wars and covert operations over the past few decades but the President’s action on this occasion are noble and praiseworthy. What a man! And what an American!”

The problems arising from Blackmon’s concluding plea (quoted at the top of this article) emanate from this lopsided sense of self-righteousness which soon clings to it in real life. This only becomes apparent when we consider the extent of this hoped for empathy and its final destination. It is perfectly fine if this empathy ends with our pocketbooks and non-violent service but there is little doubt that war and sometimes devastating sanctions are offered as solutions to the difficulties of delivering aid or ridding the world of despots—as a tool to protect those most vulnerable.

It seems to me that the American government has used this “empathy” (actually more like cursory interest) for their own ends over the last few years. A prime example of the “Too Much Empathy” brigade might be UN Ambassador Samantha Power who is the authoress of the Pultizer Prize winning book, A Problem from Hell, and who is now a vehement and consistent supporter of American Interventionalism. She is a self-described “humanitarian hawk.” Just think of the tragedies and foment the current administration has managed to stir up in places like Libya, Syria and Ukraine in the name of democracy and human rights. These actions would not have worked quite as well without a sprinkling of empathy largely generated by the news media. Lord save us from even more desultory “empathy” from shows like The Walking Dead.

What the world really needs is more “real” knowledge. If we feel that Yarmouk camp in Damascus is a tragedy which requires decisive action, should we find only Bashar al-Assad guilty or do we also consider the actions of some likely instigators worthy of reproof:

“In January, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a report on the assault by a local militia in September 2012 on the American consulate and a nearby undercover CIA facility in Benghazi… A highly classified annex to the report, not made public, described a secret agreement reached in early 2012 between the Obama and Erdogan administrations. It pertained to the rat line. By the terms of the agreement, funding came from Turkey, as well as Saudi Arabia and Qatar; the CIA, with the support of MI6, was responsible for getting arms from Gaddafi’s arsenals into Syria.”

Or to take an even more extreme case, if we feel horrified by the Rwandan genocide, should we not also consider American complicity in the Rwandan Patriotic Front’s (RPF) invasion of Rwanda prior to the genocide and the vigorous French support for the genocidaires themselves? Who then do we support? The ones who triggered the genocide or the ones who fanned it? It would appear that the problems of this world are not quite as easily fixed as those resolved by shooting a girl in the head.

Consider one solution to this “white man’s burden” proffered by former army colonel and Professor of International Relations and History at Boston University, Andrew Bacevich, a few years back. In answer to an audience member who wondered if the de-escalation of U.S. activities in the Middle East would encourage militants and be an abandonment of those most in need, he suggested that Americans should instead consider inviting more citizens of those nations back to the comparative safety of the United States for educational experience. Not a magic bullet to solve all ills but infinitely preferable to the dropping of bombs. Perhaps even the beginning of empathy.