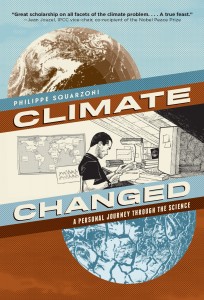

Right now, I’m reading Philippe Squarzoni’s Climate Changed: A Personal Journey through the Science with great interest and satisfaction. Squarzoni walks us through his own navigation of the complex topic, and thereby provides us with at least two things simultaneously: the record of one man’s autodidactic process in the face of a phenomenon he wishes to understand more fully, plus a primer for all of us to use for our own education in climate science.

The book is elegantly drawn, with calm, clear-line precision (a helpful contrast to the messy and disturbing nature of the topic itself), and the text has elements of memoir, reportage, and speculative essay, offered to English-speaking readers through the smooth translation of Ivanka Hahnenberger. I feel like I’m reading something important and timely as I move through Squarzoni’s graphic narrative, and it is an added bonus to hear and watch Squarzoni grapple with the implications of his research for himself, for his family, and for all of us sharing the planet with him.

This experience got me thinking about other works in comics format (digital or print)–suitable for adults–that take up scientific or mathematical concepts while using the medium advantageously. I found it difficult to think of many off the top of my head, and this seemed to contrast with the lengthy list I could produce if asked to consider cultural and political issues presented in graphic reportage format. We have a bumper crop of the latter (which is great), but far fewer of the former. In light of our recent PencilPanelPage roundtable on Groensteen and panel shapes, an additional criterion presents itself: who is doing good science in their comics, but also good comics while they do good science? Who is innovating layout and breakdown in service of scientific concepts? This question isn’t rhetorical; let the recommendations flow in the comments section!

So, here are the science comics I’m familiar with:

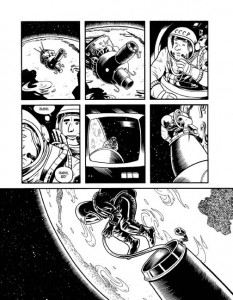

Anything by Jim Ottaviani. I’m a fan: Ottaviani and his various illustrators do justice to both the history of science and to scientific concepts, in works such as Two-Fisted Science, T-Minus: The Race to the Moon (with Zander Cannon and Kevin Cannon), and, recently, Feynman (with Leland Myrick).

Another major player: Larry Gonick, with his Cartoon Guides to . . . (Physics, Chemistry, the Environment, etc.).

The Manga Guide to . . . series (various authors and artists) put out by No Starch Press offers another take, but I’m not sure I’d include either of the previous two series in a short- (or long-) list of avant-garde comics qua comics.

On the webcomics front, I am fond of Rosemary Mosco’s Bird and Moon, which offers charming doses of ornithology and botany,

and Katie McKissick’s Beatrice the Biologist, which is a multimodal blog that uses video, comics, and traditional text to explain scientific concepts and promote scientific literacy.

Another talented science popularizer is the Dutch cartoonist, Margreet de Heer, who produces webcomics at her site,

and whose Science: A Discovery in Comics is available in English translation from NBM Publishing.

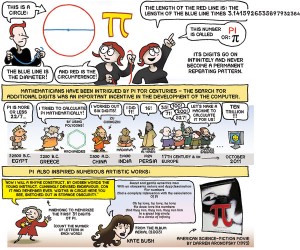

Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papadimitriou paired up to produce Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth, a compelling—and by now, highly esteemed—graphic narrative that explores mathematical concepts and features Bertrand Russell as its main protagonist. You’ve probably read it, but here’s a sample page anyway:

Logicomix has great “crossover appeal,” and is read across disciplinary lines, with humanists as interested as mathematicians, not to mention lay people who enjoy intellectual biographies and origin stories. Text and image work well together in this work, both offering a sophisticated, inviting intimacy for the reader, but the general adherence to basic grid format does not allow for a layout that particularly and specifically suits the concepts it presents.

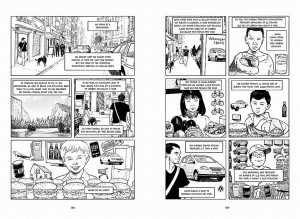

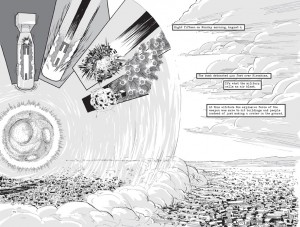

Here, on the other hand, is a work that just might qualify for the “good science, good comics” designation: Jonathan Fetter-Vorm’s Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb. Look at these two pages:

Trinity, in fact, is full of pages that differ from each other, and each has been carefully constructed to echo and enhance the presentation of certain types of information. Fetter-Vorm (albeit not a scientist) is on to something, I think, working with panel shapes actively, making them serve and clarify the idea presented (panels are collapsed, eliminated, intentionally shaped, imploded, broken)—how perfect for explaining the mechanics of Fat Man and Little Boy!

So, as much as I admire the works I’ve mentioned above for different reasons, I was only able to offer a single example of avant-garde comics layout housing accurate and instructive science. What am I missing?