>

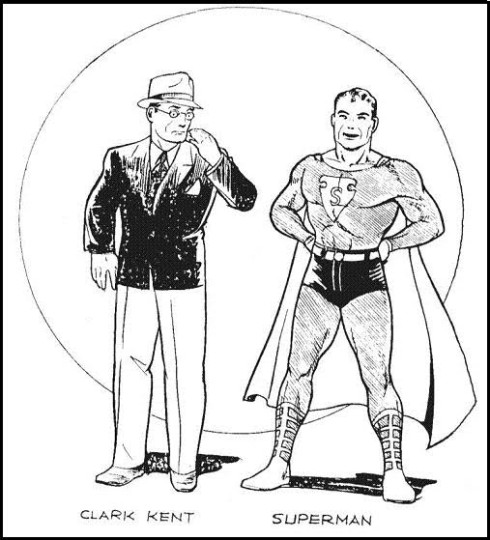

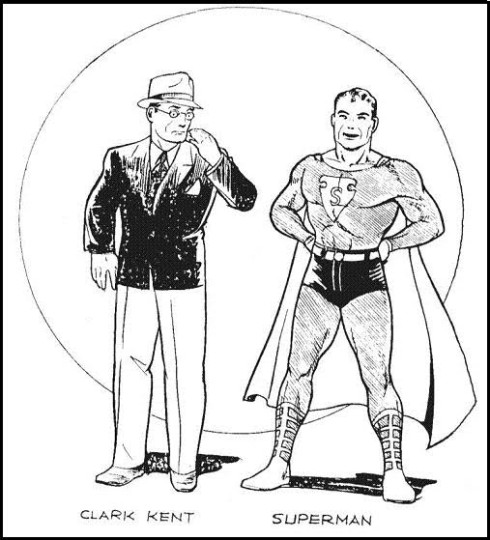

Art by Joe Shuster

Once commentators could discuss the “Superman”, the “Super-Race”, and the “Super-Society” without drawing connections back to the philosophy from whence it sprang, the Uebermensch proved to be a concept able to accommodate any number of competing moral viewpoints. And once Nietsche could become a thinker with answers but no questions, and his philosophy a celebration of power rather than a testament to the need for human wonder, the Uebermensch’s naturalization into American intellectual and cultural life was successfully under way.

– Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche

See you in the Funny Papers

In the 1890’s an extremely successful new pop medium took off: the newspaper comic strip.

Millions of readers delighted in the daily comedy antics of the Katzenjammer Kids, Buster Brown, or Mutt and Jeff. The strips ran in black-and-white, but in 1897 the New York Journal published the first full-color Sunday comics supplement. In 1924 appeared what is generally considered to be the first adventure comic strip: Wash Tubbs, by Roy Crane (1901–1977).

Art by Roy Crane; click on image to enlarge

This opened the way for such classic adventure series as Terry and the Pirates, Prince Valiant, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy.

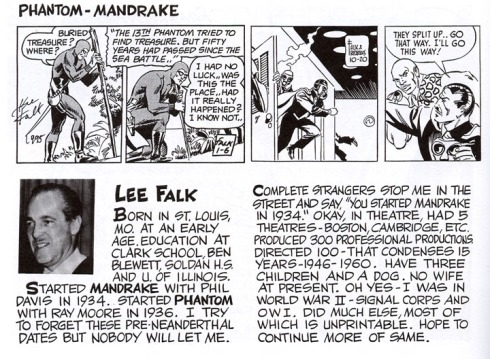

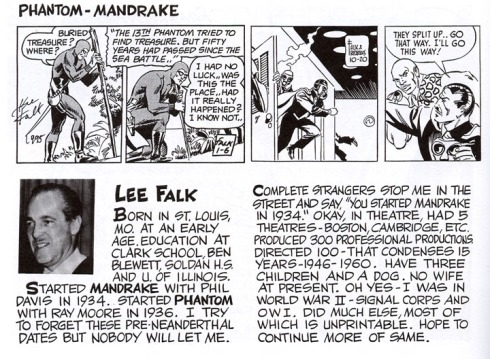

The man who introduced the superhero to the comic strip was scripter Lee Falk(1911–1999). He created Mandrake the Magician in 1934, a dapper wizard who wielded his stupendous hypnotic powers against such villains as the Cobra and the Deleter.

Art by Phil Davis (1906-1964)

Mandrake has been the springboard for subsequent magician superheroes such as Ibis the Invincible, Dr Strange, or Zatara. Sometimes the imitation verged on plagiarism: witness Zatara:

Art by Fred Guardineer

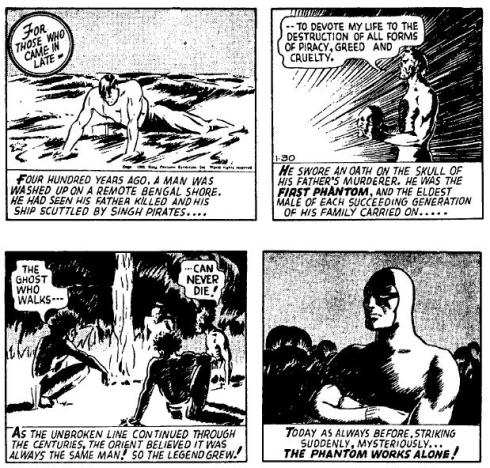

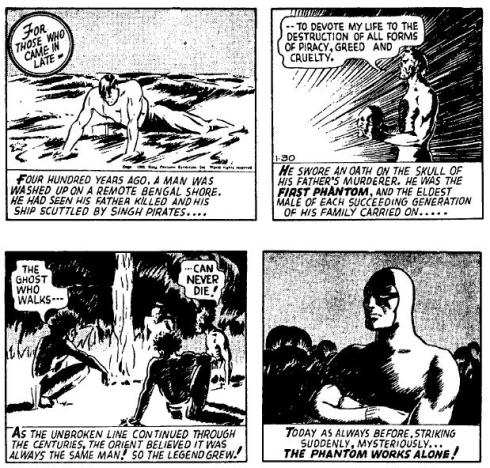

Falks’ other classic superhero creation was the Phantom of Bengal (1936).

The Phantom had an original backstory: Kit Walker was the 21st Phantom in a lineage stretching back to his ancestor in 1516. By adopting the same mask and costume generation after generation, the Phantoms created the legend of an immortal fighter for justice:

Art by Ray Moore (1905-1984); click on image to enlarge

The Phatom‘s costume pioneered several of the visual tropes associated with superheroes ever since: form-fitting top and tights, with the elegant innovation of underpants worn on the outside; a skull-hugging hood; and a mask with blanks hiding the eyes. All he lacked was a cape — which deficiency Mandrake supplied. Compare the Phantom to such later superheroes like Batman and Captain America, and it’s obvious how much the latter owe to Falks’ design.

All in Color for a Dime

Comic strips from the start would be gathered into book editions, with cardboard covers, much like modern European albums; they were relatively expensive gift items.

In 1929, Dell Publishing brought out a tabloid-sized newspaper supplement of color strip reprints, The Funnies, which ran for a year; in 1933, Eastern Color Printing published a reprint pamphlet titled Funnies on Parade, featuring popular strips such as ‘Mutt and Jeff’, ‘Joe Palooka‘, and ‘Skippy‘. It’s considered by many to be the first true American comic book — with minor changes of format and printing technology, 2012 comic books resemble 1933 ones.

Funnies on Parade was devised chiefly as a way to keep Depression-idled printing presses busy. It was never sold, but used as a promotional giveaway by Procter and Gamble; everybody thought there was no money to be made selling what came free with the daily newspaper.

But Eastern Color’s salesman, Max Gaines, was sure there was a market out there, and so there was issued in May 1934 Famous Funnies, a 64-page reprint magazine retailing at 10 cents. It sold an incredible 90% of its print run. A new media industry was born.

Cover illustration by Jon Mayes

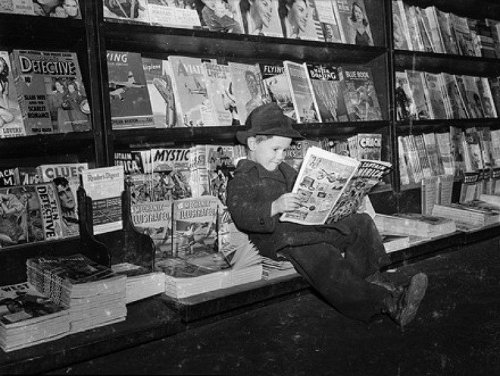

The newsstands were soon flooded with comic books. It’s not hard to understand their appeal; in our age of i-Pads and portable television, we have to remember that back in the 1930s immersive visual entertainment was limited to movie theatres.

The strip syndicates furnished the editorial content. This posed two problems: first, that the ravenous demand for comic books was quickly using up the available material; next, that the syndicates were charging some $10 per page, which cut cruelly into the profit margins.

The solution was to create new material at, say, $5 per page. Of course, such a fee would never attract established professional cartoonists; but, then as now, a horde of eager youths stood ready to write and draw for miserable wages, perhaps as a stepping-stone to the lucrative strip market. And the publishers were more than willing to exploit them.

Needless to say, this was a recipe for dreadful comics: inexperienced youngsters forced to hack out stories as fast as possible to earn a decent living. On the plus side, these tyros had youth’s energy and invention.

Although some new material had been incorporated from the start of the boom, generally the credit for the first all-new material comic book has been given to Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson‘s New Fun comics. It featured a mix of humor and adventure tales; some of the latter were provided by the teen-aged combo ofJerry Siegel (script) and Joe Shuster (art). We shall come back to this pair later on.

The pulps had found formidable competition for the reader’s dime. The more astute pulp publishers were quick to bring out comic books, often cartoon versions of their prose magazines; thus Fiction House simultaneously brought out, in 1939, the science-fiction pulp Planet Stories and its comic book sister, Planet Comics.

As we saw in the last chapter, the pulps had abundantly featured masked super-heroes. It is therefore logical that pulp and comic book publisher Centaur Publications should debut, in 1936’s Funny Picture Stories, the first original comic book superhero: The Clock, the secret identity of society swell Brian O’Brien.

But far from this publishing sideshow, 1933 is a year chiefly remembered for a dark and world-changing occurrence on the other side of the Atlantic: on January 30, President Paul Von Hindenburg appointed the leader of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, Adolph Hitler, the Chancellor of Germany.

The Nazis were now in power.

Hoch der Uebermensch!

In the decades since Nietzsche had formulated the concept and the wordUebermensch (generally translated into English as “superman” ), the notion had been warped and twisted into strange shapes indeed.

For Nietzsche, the superman was a spiritual goal for every human being, a new type unhindered by religion’s focus on the world to come — rather, revelling in the material world, placing body above soul, and dedicated to discovering new values by which to live.

But what the culture at large retained was the word: superman. It became what we would now call a meme. And it came to be attached to the strongest, most world-changing idea of the late 19th century: evolution.

The Darwinian revolution — postulating the emergence and survival of species by mutation and selection — was often misunderstood, and its revelations misapplied. The idea of evolution ( a term Darwin himself was uncomfortable with, preferring “descent through modification”) seemed to imply that humanity could be transforming itself into a superior species — or at least some “races” of humanity could.

Pseudo-scientific racism was spawned in the latter half of the 19th century, from the Frenchman de Gobineau‘s An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races(1855) through Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton< and his invention of the concept (and word) eugenics.

Illustration for the 2nd Congress of Eugenics (1921). Click image to enlarge.

Eugenics is an ideology that calls for the preservation or improvement of human genetic stock by encouraging “superior” individuals, and discouraging “inferior” ones, to breed. From the vantage point of the 21st century, after a hundred years of horror and suffering inflicted by such ‘scientific’ racism, it is hard to wrap our heads around the idea that this was once considered a humane and socially progressive idea; yet champions of eugenics included such forward-thinking persons as H.G.Wells, Margaret Sanger, George Bernard Shaw andSydney Webb.

And the first country to forcibly apply eugenics by law? The United States of America, where from 1907 to 1963 64000 forced sterilisations of “imbeciles”, “hereditary criminals” and other “degenerates” were carried out — 20,000 in California alone. (America was also the land where the term “master race” was coined, to justify Southern slavery.)

It remained for certain ideologues to push the folly of eugenics even further, to advocate the extermination of ‘sub-human’ peoples — Untermenschen — such as the Jews and Gypsies, while seeking to breed a new race of masters– of Uebermenschen — of supermen.

These were the murderous Nazis, who had seized absolute power in Germany.

And their goal of extermination was hideously implemented in the Holocaust.

Their breeding program– the Lebensborn project — aimed at refining a supreme Nordic race. As SS leader Heinrich Himmler detailed it in 1936:

The organization “Lebensborn e.V.” serves the SS leaders in the selection and adoption of qualified children. The organisation “Lebensborn e.V.” is under my personal direction, is part of the race and settlement central bureau of the SS, and has the following obligations:

-

1. Support racially, biologically, and hereditarily valuable families with many children.

-

2. Place and care for racially and biologically and hereditarily valuable pregnant women, who, after thorough examination of their and the progenitor’s families by the race and settlement central bureau of the SS, can be expected to produce equally valuable children.

-

3. Care for the children.

-

4. Care for the children’s mothers.

–objectives that expanded to the kidnapping of ‘racially desirable’ children in such conquered lands as Norway, Denmark and Poland, to be Germanised and raised as the vanguard of a new race of superior beings.

German propaganda poster, 1942. Note the contrast between the calm, strong “Uebermensch” German soldier and the defeated, multiracial French prisoners in the background.

(Before crossing the Atlantic back to the USA, let me repeat that Nietzsche himself was, contrary to popular modern conception, not at all a proponent of the sort of ruthless evolutionary pruning that characterised social Darwinists and eugenics enthusiasts:

There is rarely a degeneration, a truncation, or even a vice or any physical or moral loss without an advantage somewhere else. In a warlike and restless clan, for example, the sicklier man may have occasion to be alone, and may therefore become quieter and wiser; the one-eyed man will have one eye the stronger; the blind man will see deeper inwardly, and certainly hear better. To this extent, the famous theory of the survival of the fittest does not seem to me to be the only viewpoint from which to explain the progress of strengthening of a man or of a race. — Friedrich Nietzche, Human, All too Human (1876)

He was also contemptuous of both nationalism and of racism; he proposed to deal with anti-Semitism by shooting anti-Semites in the face.)

Thus the idea of the superman was very much “in the air”– not just in Germany, but worldwide– in the early 1930s.

And this idea would bloom in the imagination of one teen-aged boy from Cleveland, Ohio, who would revolutionise the new comic-book field.

Man of Steel — and of Paper

The science fiction pulps spawned an exceptionally active and intelligent fandom from the start. Many of the greatest writers in SF history started out as teen-aged members of such fan clubs as the Futurians or the Science Fiction League: Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, Donald Woolheim, Cyril Kornbluth. Other science fiction fans of the 30’s went on to be editors, some of comic books: Mort Weisinger, Julius Schwartz (both of whom would serve as Superman editors for decades.)

In Cleveland, Ohio, young Jerry Siegel (1914 — 1996) was one of the earliest SF fans: in 1929, at the age of fifteen, he produced what may be the first science-fiction fanzine, Cosmic Stories, on his typewriter– carbon copies were his ‘printing press’. When he was 16, Siegel met teen-aged artist Joe Shuster (1914 — 1992) at high school; they immediately clicked — ‘When Joe and I first met, it was like the right chemicals coming together’.

They put out a mimeographed fanzine together: Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilisation, in the third issue of which — in June 1932– they published the following story, written by Siegel (under the pen name Herbert S. Fine), illustrated by Shuster:

click on image to enlarge

This Superman was an evil tyrant with psychic powers. Siegel, later in life, recalled how the word and concept of a superman was much discussed at the time, in tandem with the rise of Naziism in Germany. Both Siegel and Shuster were Jews; this evil ur-Superman likely reflected alarm over growing Nazi power.

But the next iteration of Superman was a force for good; in addition to the obvious wish-fulfillment fantasies it represented, I suspect there was also a desire to appropriate and reclaim the idea of the superman from Nazi ideologues.

Certainly, that’s how some Nazis saw it:

Jerry Siegel, an intellectually and physically circumcised chap who has his headquarters in New York, is the inventor of a colorful figure with an impressive appearance, a powerful body, and a red swim suit who enjoys the ability to fly through the ether.

The inventive Israelite named this pleasant fellow with an overdeveloped body and underdeveloped mind “Superman.” He advertised widely Superman’s sense of justice, well-suited for imitation by the American youth.

As you can see, there is nothing the Sadducees won’t do for money!

Jerry looked about the world and saw things happening in the distance, some of which alarmed him. He heard of Germany’s reawakening, of Italy’s revival, in short of a resurgence of the manly virtues of Rome and Greece. “That’s great,” thought Jerry, and decided to import the ideas of manly virtue and spread them among young Americans. Thus was born this “Superman.” […] Woe to the youth of America, who must live in such a poisoned atmosphere and don’t even notice the poison they swallow daily.

(Das Schwarze Korps, April 25, 1940.)

(This was in response to a two-page strip done for Look magazine, in whichSuperman smashes the German army and brings Hitler and Stalin before the League of Nations for judgment.)

In 1933, Siegel and Shuster produced sample strips of Superman with a view to newspaper syndication. This version of the character differed visually from the one we know, chiefly in his lack of costume:

art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

The above illustration shows another strong influence on Superman’s genesis, the pulp hero Doc Savage. Consider the below house advertisement for Doc:

>

click on image to enlarge

Now began a five-year effort to sell the strip. It was turned down time and again by the syndicates. One editor commented: “The trouble with this, kid, is that it’s too sensational. Nobody would believe it.” Bell Syndicate told them, “We are in the market only for strips likely to have the most extra-ordinary appeal, and we do not feel Superman gets into this category.” United Features said that Superman was “a rather immature piece of work.”

As Jim Steranko put it, the world’s hottest property was gathering dust on the shelf.

Meanwhile, Siegel and Shuster were making a living in the new market of original-material comic books, telling the adventures of Dr Occult and Slam Bradley. They tried re-tooling the strip for this market; still no success. Shuster, in a fit of despair, burned all his sample pages; Siegel was only able to salvage the cover:

art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

This act of destruction cleared the way for a new version. There was a new outfit, obviously inspired by newspapers’ The Phantom and by circus performers. As Shuster noted, they had created a “kind of costume and let’s give him a big S on his chest, and a cape, make him as colorful as we can and as distinctive as we can.” This showbiz instinct was tremendously prescient. The image of Superman is recognised the world over — a marvellous branding success — and has been imitated by countless superhero characters up to the present day.

Joe Shuster at the drawing board, with Jerry Siegel hovering; click on photo to enlarge

Finally, the two creators were able to place the strip with Max Gaines at National Allied Publications — the future DC comics. It was looked on almost as filler material — editor Vin Sullivan didn’t have enough strips to round out Action Comics 1. Still, Superman was splashed on the cover — a cover that almost went unused because Gaines felt it was too silly:

art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

And indeed, even a year later, despite the character’s unheard-of popularity,Superman wasn’t the main cover feature on every issue–as shown in this 1939 house ad:

art by Fred Guardineer

The comic came out on April 18, 1938. It was an instant sellout. The age of the superhero comic book was born — and continues today, in a much-etiolated, decadent form, totally dominating popular comic books — to the point where superhero comics are actually termed ‘mainstream’. (Famously, Siegel and Shuster saw the merest trickle of the ocean of money Superman was to generate.)

The Superman of the late ’30s was an angry fellow. He battled crooked politicians and slimy capitalists– once dragging a coal tycoon down into his own unsafe mine. He grabbed generals sending soldiers to their deaths and placed them on the frontline.

This crusading attitude, as much as the dream of unlimited power, explains much of his instant appeal at the time. This was an America still crippled by the Great Depression, with the looming shadow of war causing anxiety. The ‘common man’ was frightened, exhausted, and furious. And here was this mighty champion taking on the bums of the power elite: it was a populist fantasy of revenge — the same one that Gramsci had discerned in the ‘superman’ characters of nineteenth-century popular novels, the same one that colored the dime novel Westerns, with their aggrieved outlaws.

We’ve spent the past seven columns tracing the distant origins of the superhero; a word or two on the immediate influences that fed the imagination of Superman’s creators.

Siegel mentioned, besides the Uebermensch concept, the swashbuckling movie characters of Douglas Fairbanks: among these, as seen in part 6 of this study, was the proto-superhero Zorro. He also cited Tarzan; but the latter’s creator–Edgar Rice Burroughs — surely also contributed the conceit of a visitor to another planet gaining super-strength and the ability to leap vast distances from gravity lower than his homeworld’s, in the John Carter of Mars stories.

The Doc Savage influence is manifest, even in small details: the name of Superman’s alter-ego Clark Kent echoes Doc’s own, Clark Savage Jr; Doc had a Fortress of Solitude before Superman did; Doc was billed the Man of Bronze, while Superman was the Man of Steel.

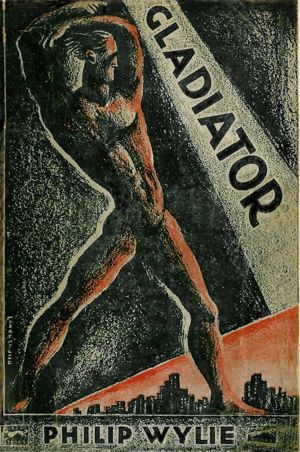

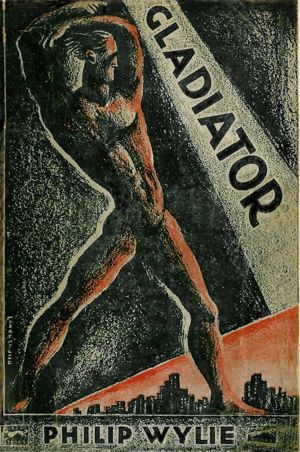

There’s controversy over the influence of a 1930 novel by Philip Wylie(1902–1971), Gladiator.

The hero of Gladiator, Hugo Danner, exhibits powers identical to those ofSuperman‘s in his first appearances: herculean strength, bulletproof skin, the ability to leap great distances. Danner got his power as a result of his scientist father’s attempt to replicate the proportional strength of insects; now read this early presentation of Superman, with a note at the end on his power:

art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

Wylie, in a 1963 interview with science fiction historian Sam Moscowitz, claimed that Superman was plagiarised from Gladiator, and that he’d threatened to sue Siegel and the publisher in 1940.

Siegel, for his part, denied ever reading Wylie’s book. It would seem plausible, as the novel had only sold some 2000 copies. And that comparison of insect strength in proportion to our own was already pretty old hat in 1938. But there’s a smoking gun: Siegel had reviewed the book in his fanzine Science Fiction…whose next issue featured ‘Reign of the Superman’.

Finally, an unconscious influence may be traced to Siegel’s Jewish heritage. Superman seems like a parody of the Messiah, sent from the heavens to redeem mankind. He is also strongly reminiscent of the legendary Golem of Prague, who with his superhuman strength protected the Jews against their oppressors.

An intriguing theory, but perhaps a far-fetched one.

Next: Inventory and Conclusion