Comics asks that you join it in observing a moment of silence.

Comics is staunchly anti-censorship. We shall discuss this in due time, after the moment of silence.

No, not yet. Hush, now. For freedom. For Comics!

Comics isn’t sure about the kids these days, to be honest.

Comics worries the next generation might not read the right things. Sometimes Comics can’t sleep at night, for all the worrying.

Comics wonders if you plan to wear a sweater. It’s supposed to get chilly, you know.

Also pack some extra socks. It’s good for Comics.

Comics has put together a big book of newspaper clippings for posterity. Comics someday hopes to print and collate corresponding threads from the most essential message boards.

What’s a Tumblr, Comics wonders. It sounds stupid.

Comics respects women. Obviously.

Why? Because Comics says so, that’s why.

Psssh. Comics is not racist. Because satire.

Comics says maybe YOU’RE the racist. Did you ever think of that?

Comics will try to speak more slowly so you can understand.

Actually…Comics.

Merica. Krazy Kat. Comics.

Comics says this is not the time or the place.

Comics says watch your tone.

Comics says that you just want attention.

Comics can’t hear you. LA-LA-LA

You are not the boss of Comics.

Comics has made a list of 500 things we can all do to improve Comics. 1. Always listen to Comics.

Comics. Comics!! COMICSSSSS

Comics had a black friend in middle school.

Homophobic? Comics has two words for you: Alison Bechdel.

Transphobic? Listen, Comics doesn’t even care about that stuff!

No, seriously. Comics doesn’t give a fuuuuuuck.

You know what Comics does care about? Art. Unlike some certain people.

You just don’t understand Art. Or history. Not like Comics does.

Comics only wants what’s best for you. Someday you’ll understand.

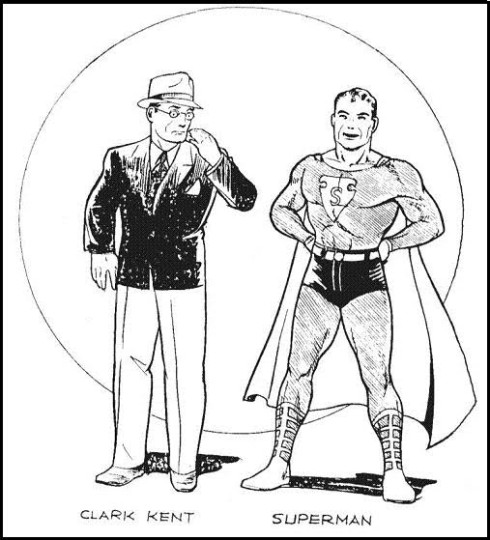

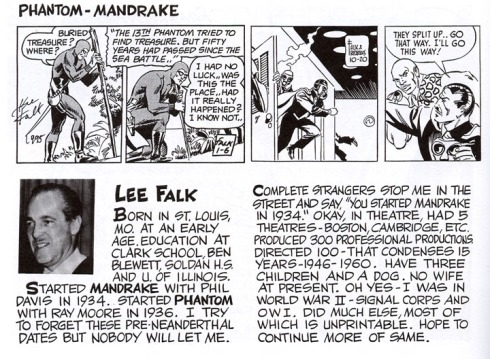

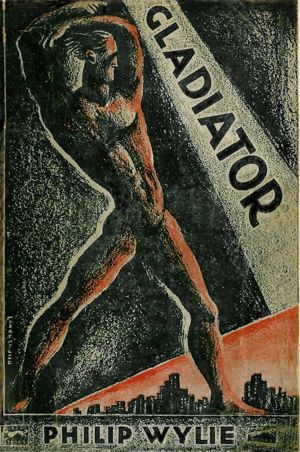

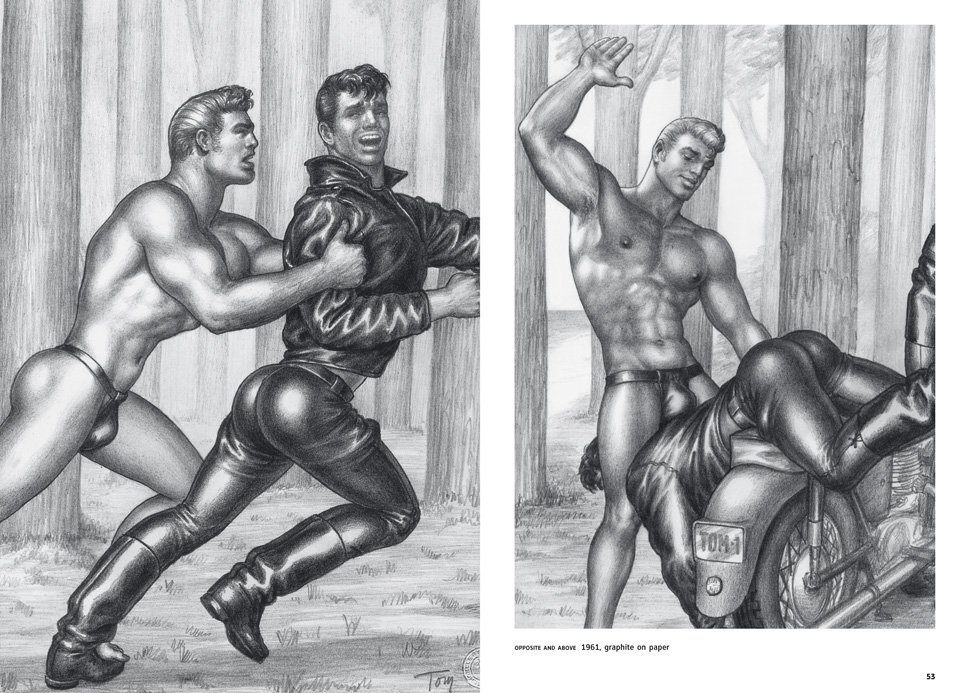

Anyway, this isn’t about you. It’s about me. I mean, Comics. Once commentators could discuss the “Superman”, the “Super-Race”, and the “Super-Society” without drawing connections back to the philosophy from whence it sprang, the Uebermensch proved to be a concept able to accommodate any number of competing moral viewpoints. And once Nietsche could become a thinker with answers but no questions, and his philosophy a celebration of power rather than a testament to the need for human wonder, the Uebermensch’s naturalization into American intellectual and cultural life was successfully under way. In the 1890’s an extremely successful new pop medium took off: the newspaper comic strip. Millions of readers delighted in the daily comedy antics of the Katzenjammer Kids, Buster Brown, or Mutt and Jeff. The strips ran in black-and-white, but in 1897 the New York Journal published the first full-color Sunday comics supplement. In 1924 appeared what is generally considered to be the first adventure comic strip: Wash Tubbs, by Roy Crane (1901–1977). The man who introduced the superhero to the comic strip was scripter Lee Falk(1911–1999). He created Mandrake the Magician in 1934, a dapper wizard who wielded his stupendous hypnotic powers against such villains as the Cobra and the Deleter. Comic strips from the start would be gathered into book editions, with cardboard covers, much like modern European albums; they were relatively expensive gift items. In 1929, Dell Publishing brought out a tabloid-sized newspaper supplement of color strip reprints, The Funnies, which ran for a year; in 1933, Eastern Color Printing published a reprint pamphlet titled Funnies on Parade, featuring popular strips such as ‘Mutt and Jeff’, ‘Joe Palooka‘, and ‘Skippy‘. It’s considered by many to be the first true American comic book — with minor changes of format and printing technology, 2012 comic books resemble 1933 ones. But Eastern Color’s salesman, Max Gaines, was sure there was a market out there, and so there was issued in May 1934 Famous Funnies, a 64-page reprint magazine retailing at 10 cents. It sold an incredible 90% of its print run. A new media industry was born. The strip syndicates furnished the editorial content. This posed two problems: first, that the ravenous demand for comic books was quickly using up the available material; next, that the syndicates were charging some $10 per page, which cut cruelly into the profit margins. The solution was to create new material at, say, $5 per page. Of course, such a fee would never attract established professional cartoonists; but, then as now, a horde of eager youths stood ready to write and draw for miserable wages, perhaps as a stepping-stone to the lucrative strip market. And the publishers were more than willing to exploit them. Needless to say, this was a recipe for dreadful comics: inexperienced youngsters forced to hack out stories as fast as possible to earn a decent living. On the plus side, these tyros had youth’s energy and invention. Although some new material had been incorporated from the start of the boom, generally the credit for the first all-new material comic book has been given to Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson‘s New Fun comics. It featured a mix of humor and adventure tales; some of the latter were provided by the teen-aged combo ofJerry Siegel (script) and Joe Shuster (art). We shall come back to this pair later on. The pulps had found formidable competition for the reader’s dime. The more astute pulp publishers were quick to bring out comic books, often cartoon versions of their prose magazines; thus Fiction House simultaneously brought out, in 1939, the science-fiction pulp Planet Stories and its comic book sister, Planet Comics. As we saw in the last chapter, the pulps had abundantly featured masked super-heroes. It is therefore logical that pulp and comic book publisher Centaur Publications should debut, in 1936’s Funny Picture Stories, the first original comic book superhero: The Clock, the secret identity of society swell Brian O’Brien. The Nazis were now in power. In the decades since Nietzsche had formulated the concept and the wordUebermensch (generally translated into English as “superman” ), the notion had been warped and twisted into strange shapes indeed. For Nietzsche, the superman was a spiritual goal for every human being, a new type unhindered by religion’s focus on the world to come — rather, revelling in the material world, placing body above soul, and dedicated to discovering new values by which to live. But what the culture at large retained was the word: superman. It became what we would now call a meme. And it came to be attached to the strongest, most world-changing idea of the late 19th century: evolution. The Darwinian revolution — postulating the emergence and survival of species by mutation and selection — was often misunderstood, and its revelations misapplied. The idea of evolution ( a term Darwin himself was uncomfortable with, preferring “descent through modification”) seemed to imply that humanity could be transforming itself into a superior species — or at least some “races” of humanity could. Pseudo-scientific racism was spawned in the latter half of the 19th century, from the Frenchman de Gobineau‘s An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races(1855) through Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton< and his invention of the concept (and word) eugenics. And the first country to forcibly apply eugenics by law? The United States of America, where from 1907 to 1963 64000 forced sterilisations of “imbeciles”, “hereditary criminals” and other “degenerates” were carried out — 20,000 in California alone. (America was also the land where the term “master race” was coined, to justify Southern slavery.) It remained for certain ideologues to push the folly of eugenics even further, to advocate the extermination of ‘sub-human’ peoples — Untermenschen — such as the Jews and Gypsies, while seeking to breed a new race of masters– of Uebermenschen — of supermen. These were the murderous Nazis, who had seized absolute power in Germany. And their goal of extermination was hideously implemented in the Holocaust. Their breeding program– the Lebensborn project — aimed at refining a supreme Nordic race. As SS leader Heinrich Himmler detailed it in 1936: The organization “Lebensborn e.V.” serves the SS leaders in the selection and adoption of qualified children. The organisation “Lebensborn e.V.” is under my personal direction, is part of the race and settlement central bureau of the SS, and has the following obligations: 1. Support racially, biologically, and hereditarily valuable families with many children. 2. Place and care for racially and biologically and hereditarily valuable pregnant women, who, after thorough examination of their and the progenitor’s families by the race and settlement central bureau of the SS, can be expected to produce equally valuable children. 3. Care for the children. 4. Care for the children’s mothers. –objectives that expanded to the kidnapping of ‘racially desirable’ children in such conquered lands as Norway, Denmark and Poland, to be Germanised and raised as the vanguard of a new race of superior beings. There is rarely a degeneration, a truncation, or even a vice or any physical or moral loss without an advantage somewhere else. In a warlike and restless clan, for example, the sicklier man may have occasion to be alone, and may therefore become quieter and wiser; the one-eyed man will have one eye the stronger; the blind man will see deeper inwardly, and certainly hear better. To this extent, the famous theory of the survival of the fittest does not seem to me to be the only viewpoint from which to explain the progress of strengthening of a man or of a race. — Friedrich Nietzche, Human, All too Human (1876) He was also contemptuous of both nationalism and of racism; he proposed to deal with anti-Semitism by shooting anti-Semites in the face.) Thus the idea of the superman was very much “in the air”– not just in Germany, but worldwide– in the early 1930s. And this idea would bloom in the imagination of one teen-aged boy from Cleveland, Ohio, who would revolutionise the new comic-book field. The science fiction pulps spawned an exceptionally active and intelligent fandom from the start. Many of the greatest writers in SF history started out as teen-aged members of such fan clubs as the Futurians or the Science Fiction League: Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, Donald Woolheim, Cyril Kornbluth. Other science fiction fans of the 30’s went on to be editors, some of comic books: Mort Weisinger, Julius Schwartz (both of whom would serve as Superman editors for decades.) In Cleveland, Ohio, young Jerry Siegel (1914 — 1996) was one of the earliest SF fans: in 1929, at the age of fifteen, he produced what may be the first science-fiction fanzine, Cosmic Stories, on his typewriter– carbon copies were his ‘printing press’. When he was 16, Siegel met teen-aged artist Joe Shuster (1914 — 1992) at high school; they immediately clicked — ‘When Joe and I first met, it was like the right chemicals coming together’. They put out a mimeographed fanzine together: Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilisation, in the third issue of which — in June 1932– they published the following story, written by Siegel (under the pen name Herbert S. Fine), illustrated by Shuster: But the next iteration of Superman was a force for good; in addition to the obvious wish-fulfillment fantasies it represented, I suspect there was also a desire to appropriate and reclaim the idea of the superman from Nazi ideologues. Certainly, that’s how some Nazis saw it: Jerry Siegel, an intellectually and physically circumcised chap who has his headquarters in New York, is the inventor of a colorful figure with an impressive appearance, a powerful body, and a red swim suit who enjoys the ability to fly through the ether. The inventive Israelite named this pleasant fellow with an overdeveloped body and underdeveloped mind “Superman.” He advertised widely Superman’s sense of justice, well-suited for imitation by the American youth. As you can see, there is nothing the Sadducees won’t do for money! Jerry looked about the world and saw things happening in the distance, some of which alarmed him. He heard of Germany’s reawakening, of Italy’s revival, in short of a resurgence of the manly virtues of Rome and Greece. “That’s great,” thought Jerry, and decided to import the ideas of manly virtue and spread them among young Americans. Thus was born this “Superman.” […] Woe to the youth of America, who must live in such a poisoned atmosphere and don’t even notice the poison they swallow daily. (Das Schwarze Korps, April 25, 1940.) (This was in response to a two-page strip done for Look magazine, in whichSuperman smashes the German army and brings Hitler and Stalin before the League of Nations for judgment.) In 1933, Siegel and Shuster produced sample strips of Superman with a view to newspaper syndication. This version of the character differed visually from the one we know, chiefly in his lack of costume: As Jim Steranko put it, the world’s hottest property was gathering dust on the shelf. Meanwhile, Siegel and Shuster were making a living in the new market of original-material comic books, telling the adventures of Dr Occult and Slam Bradley. They tried re-tooling the strip for this market; still no success. Shuster, in a fit of despair, burned all his sample pages; Siegel was only able to salvage the cover: And indeed, even a year later, despite the character’s unheard-of popularity,Superman wasn’t the main cover feature on every issue–as shown in this 1939 house ad: The Superman of the late ’30s was an angry fellow. He battled crooked politicians and slimy capitalists– once dragging a coal tycoon down into his own unsafe mine. He grabbed generals sending soldiers to their deaths and placed them on the frontline. This crusading attitude, as much as the dream of unlimited power, explains much of his instant appeal at the time. This was an America still crippled by the Great Depression, with the looming shadow of war causing anxiety. The ‘common man’ was frightened, exhausted, and furious. And here was this mighty champion taking on the bums of the power elite: it was a populist fantasy of revenge — the same one that Gramsci had discerned in the ‘superman’ characters of nineteenth-century popular novels, the same one that colored the dime novel Westerns, with their aggrieved outlaws. We’ve spent the past seven columns tracing the distant origins of the superhero; a word or two on the immediate influences that fed the imagination of Superman’s creators. Siegel mentioned, besides the Uebermensch concept, the swashbuckling movie characters of Douglas Fairbanks: among these, as seen in part 6 of this study, was the proto-superhero Zorro. He also cited Tarzan; but the latter’s creator–Edgar Rice Burroughs — surely also contributed the conceit of a visitor to another planet gaining super-strength and the ability to leap vast distances from gravity lower than his homeworld’s, in the John Carter of Mars stories. The Doc Savage influence is manifest, even in small details: the name of Superman’s alter-ego Clark Kent echoes Doc’s own, Clark Savage Jr; Doc had a Fortress of Solitude before Superman did; Doc was billed the Man of Bronze, while Superman was the Man of Steel. There’s controversy over the influence of a 1930 novel by Philip Wylie(1902–1971), Gladiator. Siegel, for his part, denied ever reading Wylie’s book. It would seem plausible, as the novel had only sold some 2000 copies. And that comparison of insect strength in proportion to our own was already pretty old hat in 1938. But there’s a smoking gun: Siegel had reviewed the book in his fanzine Science Fiction…whose next issue featured ‘Reign of the Superman’. Finally, an unconscious influence may be traced to Siegel’s Jewish heritage. Superman seems like a parody of the Messiah, sent from the heavens to redeem mankind. He is also strongly reminiscent of the legendary Golem of Prague, who with his superhuman strength protected the Jews against their oppressors. An intriguing theory, but perhaps a far-fetched one. I wrote this some years back for a sex toy website. I don’t think they ever published it…so I thought I’d finally run it here. “You think they [comic books] are mostly about floppy-eared bunnies, attractive little mice and chipmunks? Go take a look.” Erotic comics first surfaced in the dim dawn of pre-history among cave-dwelling ungulate-fetishists who, in animistic rituals, drew upon the stone walls choice mammoths with whom they wished to have congress. Some time thereafter, in the early 1800s, the Japanese developed…SHUNGA! Which is pretty much what it sounds like. Perhaps the most famous shunga illustration is Hokusai’s The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, which, coincidentally, also features a rape-by-mammoth. Ha ha. No, of course it doesn’t. It actually features a rape-by-octopi. Can We Get More Animation Down There, Please? If you studied the pictures above very closely, you probably need to stop and take a deep breath. If you examined them somewhat more cursorily, you probably noticed that they’re not actually comics — just influential genital progenitors, as it were. Comics as we know them coalesced as a form in the early 1900s. At first, of course, they were mostly aimed at kids, so sexual content tended to be muted. Winsor McCay drew the occasional picture of a woman in bed with a warthog, but that was about as racy as it got. No form can escape filth forever, though. By the 1920s, cutesy childhood icons were frolicking like hardened whores across the pages of crude 4″ x 6″ pamphlets known as Tijuana Bibles. Violating propriety and copyright with equal vigor, these eight-page narratives featured such familiar faces as Popeye, Dick Tracy, Flash Gordon and the eternally underage Little Orphan Annie demonstrating the use of heretofore unillustrated appendages. Tijuana Bibles were most popular during the Great Depression, when most people were too poor to afford orgasms. During the late 50s, though, men’s magazines began to publish real photographic evidence that anatomy existed, stimulating the poor Tijuana Bibles right out of existence. Balling with Gags Luckily, the girly mags were a fickle bunch; photos may have been their true love, but they inevitably had a passel of mistresses on the side. These included gag cartoons. From Eldon Didini to Jack Cole (of Plastic Man fame) to Dan DeCarlo (of Archie fame), some of the biggest names in comicdom set their work atop clever captions like “The job is yours, Miss Bigelow, providing you fit just as well on my partner’s lap!” and “Two aphrodisiacs please!” Not that anyone was looking at the captions, exactly. The pinnacle of men’s magazine cartooning is generally considered to be Little Annie Fanny, a strip cartoon which ran sporadically in Playboy from 1962 to 1988. Written by Mad-magazine alum Harvey Kurtzman and lavishly painted by Will Elder the titular character (in various senses) was an empty-headed naif who kept stumbling into preposterous situations, upon pop cultural tropes ripe for satire, and out of her clothes. Mostly that last one. Under Where? Men’s magazine illustrations were aimed at a broad, mainstream audience, and so were fairly tame by earlier illustrational standards; visible penises were a no no, much less octopus rape. With the late sixties underground comix movement, though, more idiosyncratic perversions became available from a head-shop near you. S. Clay Wilson’s raunchy fornicating bikers, satyrs, and pirates led the way, but even more influential was R. Crumb, whose comics indulged his fetish for large, powerful women and their hindquarters. In Europe, one of the most influential underground cartoonists was Touko Laaksonen, better known as Tom of Finland. His well-endowed, pumped-up, and frequently pumping leather-clad, uniform-sporting men were hugely popular through the 60s and 70s, and remain widely recognized and (ahem) utilized today. Laaksonen was even an important influence on the visual style of the Village People. Eat your heart out, Jack Kirby. The undergrounds opened the way for independent comics in general, and for more sexual and personal material in particular. At the extreme is Johnny Ryan, whose supremely and surreally filthy comics have at various points featured disembodied invisible anuses, severed butt-cracks, quarts of Dracula piss, and sex with midget Hitler. Much more literal is David Heatley’s “My Sexual History” which, like the title says, is a chronicle of every sexual encounter the author has ever had. Other autobio creators, from Jeff Brown, to Julie Doucet, to (my favorite) Ariel Schrag, have also chronicled their sexual lives in detail that veers between the arousing and the more-information-than-I-really-want-to-know-thanks. One of the most acclaimed independent adult titles is Reed Waller and Kate Worley’s 80s series, Omaha the Cat Dancer, a sexually explicit soap-opera with funny animals (the title character is actually a feline…more or less.) Equally idiosyncratic is Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s 2006 Lost Girls, which features Wendy from Peter Pan, Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz and Alice from Alice in Wonderland musing on matters philosophical while engaging in a marathon of sexual trysts. Foreign Trollops Influential European comics with sexual themes began to appear in the early 1960s. Guido Crepax’s character Valentina started her erotic run in the Italian comics magazine Linus in 1963; Crepax would go on to work on graphic adaptations of porn classics like Histoire d’O and Justine. Another Italian, Milo Manera, is perhaps Crepax’s most famous heir. Both artists have had work appear in Heavy Metal, an American offshoot of the early 70s French magazine Métal Hurlant. Heavy Metal’s Europulp-fantasy-smut remains a touchstone in American comics, from Frank Thorne’s Lann to Michael Manning’s ongoing fetish, gender-bending, humidly romantic, paranoid cyberpunk opus In A Metal Web. The real top in recent foreign-on-American porn, though, has been Japan. Manga, or Japanese comic books have penetrated…er…pushed their way into…um…stickily saturated? Anyway, they’re very popular in America, and porn manga is no exception. For those who want to be taken seriously by your local otaku, Japanese porn is usually referred to as hentai. Hentai can refer to any number of fetishes, some of which (giant breasts) are fairly mainstream, others of which (girls-with-penises, tentacle rape, or sex with underage-appearing girls, known as lolicon) are less so. From a western perspective the most unusual hentai genre,is probably yaoi. Yaoi depicts homosexual relationships between beautiful men, but it is created by and marketed mostly to women. In contrast to gay porn for gay men, yaoi tends to feature complex characters and intricate relationships — it is, in other words, a romance with lots of gay sex added. Pundits often like to claim that girls like yaoi because identifying with boys is more distant and somehow safer. Probably the real appeal is more straightforward (ahem) — if you like to look at pictures of hot guys having sex, surely two is better than one? In any case, yaoi has proved quite popular with het- (and not-so-het) female readers in the U.S. Among the most popular titles featuring boy-romance are Maki Murikami’s Gravitation and Sanami Matoh’s Fake. More consistently explicit fare includes Youka Nitta’s Embracing Love and Fumi Yoshinaga’s Gerard and Jacques. In the Future, There Will Be Only Virtual Sex Paper publishing is currently in the middle of a death-spiral, and porn comics have certainly taken a hit as well. Yes, a wide array continue to be available for all tastes, from furry-friendly-fare like Richard Moore’s Short Strokes to trans fetish fare like Roberto Baldazzini’s Bayba: The 110 BJ’s and Christian Zanier’s Banana Games to always-popular vampire erotica like Frans Mensink’s Kristina Queen of Vampires . But it seems likely that in the near future most explicitly pornographic comics will be online — like current Indian semi-sensation Savita Bhabi series. Dirty drawings never die…they just digitize. For Black Friday, I thought I’d reprint this piece about comics sales from back in 2009 — it first ran on Comixology. ________ Comics are a relatively small part of the media landscape. But how small? Or how large? How does the sale of a popular comic book compare to the sales of, say, a popular book or DVD? I wasn’t sure…so I thought I’d use this column to try and see if I could figure it out. Caveat and a half: Pretty much all of this stuff starts as guestimates made with inadequate data. By the time a non-expert like me starts talking about it…well, it’s not pretty. I think the following is useful to give some sense of the scale of the comics business compared to other entertainment industries, but any individual number should be taken with a grain of salt roughly the size of New Jersey. Marc-Oliver Frisch’s occasional column at the Beat seems like the easiest place to go for information about mainstream comics sales., at least through the direct market According to Frisch, in July of this year, the biggest seller was Marvel’s Reborn #1, which sold about 193,000 units. DC’s Blackest Night was second with sales of around 177,000 units. According to Frisch, these are fairly huge numbers, partially pumped up with variant edition covers and first issue excitement. A less hyped comic in the middle of its run – Action Comics #879 – had sales in July of 38, 324 units. Vertigo and Wildstorm titles are also in the area of 11,000 to 8000 units a month, apparently. Tiny Titans, a book for kids that’s near and dear to my heart, only sold 8, 576 units – but, again, this is through the direct market only, and I assume most of Tiny Titans sales are actually through bookstores (that’s where I get my copies., anyway.) As far as smaller press numbers, Kim Thompson, co-owner of Fantagraphics wrote me that sales are “really all over the map. A Peanuts will sell 15,000-20,000, other classics and well-known cartoonists in the 4,000-7,000 range, then all the way down to 2,000 and less for more obscure, or unsuccessful, stuff… And of course some long-time continuing books have sold a lot more than that, Ghost World at 150,000+, Palestine at 60,000+, etc.” Brian Hibbs does his best to figure out the Bookscan numbers at the end of each year, and says for comics sales through bookstores there’s about 8.3 million units sold per year, for somewhere around $100 million in sales for the top 350 books. Watchmen was the highest seller, with over 300,000 copies sold. (Though I saw a NYT article that put Watchmen graphic novel sales at 1 million…perhaps counting Direct Market and online sales as well?) Naruto v. 28 was next with over 100,000 sold. All volumes of Naruto together sold around 971,000 copies, for a total of $7.7 million. For some other numbers to throw into the mix: Brigid Alverson, who blogs over at mangablog wrote me in an email that “first printings [for manga] seem to be in the 10,000 range for smaller publishers; Yen does 25,000 for titles like Haruhi.” The folks at the Anime News Network say total sales of graphic novels in 2008 were $395 million. Manga sales accounted for $175 million of that, which is the largest single chunk (the rest being divided among super-heroes, humor, adult, etc.) They also point out the huge success of Naruto, which is so overwhelming that it’s comparable to other media products that are not comics. Like for example: Sales figures for DVDs seem a whole lot easier to obtain…as in, I googled for about 5 seconds and got actual complete information organized in a handy chart. It’s almost as if our culture cares more about DVDs. Or as if the companies aren’t embarrassed to release the information. Or something. Anyway…the biggest seller the week ending September 6 was State of Play, which sold 344,745 units. And again I say, that’s in a week. So that means that a successful DVD sells, very unscientifically, more than 6 times as much as a successful floppy comic in a given month. Watchmen the movie, a bit further down the list, is an obvious point of comparison for comics. It sold 56, 814 units in the week; still higher than any comic has done in a long time, probably, but not necessarily by many orders of magnitude. Of course, this is 7 weeks into the DVD release, and overall it’s sold more than 2 million units in that time. (Again, as best I can figure Watchmen the graphic novel seems to have sold between 300,000 to 1 million units in all of 2008.) Total DVD sales for 2008 were $14.5 billion. That’s about 36 times greater than graphic novel sales for the year, if my numbers are right. CD sales are in free fall due to the recession and that wonderful, magical whatsit we call the Internet. People still buy an awful lot of albums, though. According to the ever-erudite Ben Sisario at the NYT, the biggest seller in 2008 was Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter, which sold 2.87 million copies. Again, Watchmen, the biggest comic hit, seems to have sold less than half that, and possibly less than a quarter of that. Total music album sales (including CD, download, and LP) were 428 million. Meanwhile, over a billion songs were downloaded. The same article says that concert ticket sales clocked in at $4.2 billion in 2008. Sales of books in June were $942.6 million according to the Association of American Publishers. 2008 book sales for the year were 24 billion. I presume graphic novels are included as a part of that; if that’s correct, they’re about 1.6% of the total sales for the year…which is quite a bit smaller than I would have guessed. Also to my surprise, big-event books appear to actually outsell big-event CDs and DVDs. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows sold more than 8 million copies on its first day on sale in the U.S., which makes Lil’ Wayne’s 2.8 million albums over a year look pretty puny. And, of course, 8 million copies is just about the total bookstore sales for all graphic novels in all of 2008, according to Brian Hibbs’ figures. Obviously, Harry Potter is exceptional…but Dan Brown’s most recent book was also selling in the hundreds of thousands on its first couple of days. Breaking Dawn, the last Twilight book, sold 1.3 million copies on the first day. There’s no really startling revelations here of course. Despite big comic book derived movies and the growth of graphic novels and manga, most people in the U.S. would rather watch a movie or listen to a CD or even read a book than pick up a comic. Perhaps with the recent shake-ups at Marvel and DC that will change, and comics will start selling on a scale with other entertainment options. But, if the figures here are even close to correct, there’s a long way to go before that happens. Some years ago I was asked about the benefits of working in the comics form, as opposed to writing a novel. Since the subject at hand was a graphic novel, that is, with a fair amount of words thrown in the mix, my argument soon devolved into the classic “language vs. image” duality. It went something like this: Language is a form of communication we use to convey concrete, unambiguous information about the world. When we say “sheep,” we don’t mean “cow,” or “tree,” and we just have to assume or hope that the person we speak to knows what “sheep” means. That is the basics of language, great civilizations have been built on our mutual understanding of words like “sheep”. Of course, once we have more than one sheep, we need to specify whether it’s a ewe, a ram, or a lamb, so we invent those terms to separate one from the other. And we continue to divide the definitions into still more specific designations, until we all accept that a castrated ram is a “wether,” and the tastiest bit of a lamb is the “chop,” and so on and so forth. It wasn’t until a thousand years ago that the Japanese language got a word for the colour green, for instance, and it was still considered just a tone of blue until the advance of Crayolas in the early 20th century. Among many examples, vegetables are still called ao-mono; blue things. Images, on the other hand, are visual recordings of the world; let’s say I took a photo of a sheep. It might be my favourite sheep, we might even be intimate, but the image doesn’t say that. Now, somebody could look at the photo and project their own fear of sheep on it, not for a moment considering the luster of the pictured sheep’s wool, or the shine in its eyes. This person will just recall the trauma of the great sheep stampede of 2003, and the months spent in hospital after that. Damn sheep…! Sending an image out into the world unchecked can be a risky business, you never know how others will perceive it — and I think of the Muhammad cartoons as much as of any given person’s Facebook photos. It is said that images are worth a thousand words, but nobody said which words those are. Hardly clear-cut textbook definitions, more likely a chattering, discursive debate with itself, weighing multiple views against each other without really deciding on either, but your sister might like this, and should we maybe go for coffee somewhere? Now, that may resemble how many people actually talk, but also the way many read images, or perceive reality for that matter. So, images are intuitive, rather than specific; ambiguous rather than concrete; meandering rather than direct. They are a roundabout way of communicating, not like the above, bare-boned definition of language. Comparing the two on language’s terms isn’t really fair, images have entirely different strengths, speaking (as it were) to the viewer’s emotions, experience, and senses. More like music than like boring old text. At the same time, stylised images are used to bridge language gaps, such as in internationally standardised road signs. And sure, it’s not like language doesn’t have its ambiguities and double meanings, such as in poetry where we try to describe abstract, inner-life concepts in real-life, hands-on terms. There’s a fuzzy zone where we read images and feel language; it exists, but for the sake of argument, let’s not go there in this context. There be dragons, and wolves in sheep’s clothing. Since we’re doing the broad strokes here, I’d like to address the ways we talk about this thing we call “comics,” then. Comics as a form of communication has grown to be incredibly diverse in expression and intent. We don’t even need to go into the (perceived) mainstream just yet, when much more interesting things are happening in the “alternative” parts (ie, “everywhere else”). Gifted creators working in comic memoir, comic medicine, comic reportage, comic poetry, abstract comics, comic music, and other forms that kinda still need to be named. Mind you, in the previous sentence I’m using the word “comic(s)” due only to the sore lack of a better term. Now, I’m perfectly fine with everything from newspaper dailies to graphic novels being lumped in one category, along with the Bayeux tapestry, IKEA manuals, altarpiece triptychs, early 20th century woodcut novels, Comic Life montages, cartography, and cave paintings. What I would like is to separate the goats from the sheep, so to speak. Not in a qualitative way, as canons tend to be loaded with bias. So is the word “comics,” however, even if we have gotten used to it not being all about smart, cute kids saying adorable things, or grown men falling in banana peels. Shall I even go on to what comedians like to call themselves? At the core of it, “comics” is a nonsensical, nondescript term, used as if all film were called “talkies” still — but I’m not going to make a fuss about it like those people who recently complained about anachronistic computer interface icons. Because that was just silly, right? The world changes, and things in the world (such as desktop icons, or comics) change faster than our language can keep up. What kind of broad statement can you even make about “comics”? That they’re sequential in nature – except when they’re not? That they are all printed? Please, that had whiskers on it in the last millennium! Certainly not that they’re comical, that is to a large extent reserved for short-form “strips”, like some webcomics and the newspaper strips of old. The body of “comics” has become so complex and huge that we need to find proper names for its organs and limbs. Take the “graphic novel”. No, please, take it. That poor, abused, disowned appendix of a term. The graphic novel has been scolded for being a public relation stunt, invented to allow decent, grown-up people to read “comics”, and I couldn’t agree more. There was a time when nobody would be caught dead reading a comic, more or less because the form had been so deeply entangled with its name and the connotations of childhood silliness that went with it (When was that again, you say? Five minutes ago? Oh, how time flies), so comics was in grave need of a facelift. And it seemed to work, until some publicity smartass decided that the latest Punisher or Green Lantern collection qualified as a graphic novel, too. Then the old, trusty-as-they-are-filthy, mechanisms came into play and muddled the waters once again. We can quibble about semantics for a paragraph if you like: “Yeah, but Watchmen was serialised at first, so it’s not a graphic novel!” So was Dickens’ works. Watchmen was always intended as a finite suite of chapters, not an ongoing smack-down soap opera. Almost like a novel or something. “Even Eddie Campbell disagrees with the graphic novel tag!” Yes, well, if I read his manifesto right, he really just doesn’t accept that “graphic novel” might become a qualitaty mark to raise the price tag, or indicate that graphic novels are “better comics”. They’re not, they’re just different than some other kinds of comics. It’s a matter of intent, rather than shape or binding. End of quibble. You can see similar discussions happening over manga, or the budding scene of bandes desinees in the English language market. Geographical or cultural nomenclatures that somehow are miscontrued as genres, when they are actually as wide as, or are in fact expanding the art form we currently call, comics. We’re already burdened with the rather idiotic “OEL manga” “genre” which are just western comics influenced by Japanese comics. The fact that Western creators take inspiration from manga is perfectly legitimate, it was about time really. Again, it is the consolidation of either as a genre that raise a hackle or two — and the implication toward and among readers that there is a difference; “I don’t read comics, I only read manga.” A few examples from day-to-day media consumption: Reading a positivist blog post about a female reader who didn’t think she would be into “comics,” but elaborates how captivated she became by Wonder Woman; any which kind of media going on at length about the success of “comic book movies,” meaning the multi-feature setup for Avengers Assemble, and Nolan’s Batman flicks; academic papers promising to delve into propaganda in comics, yet touching only upon Superman or Captain America kicking Hitler’s ass, or maybe, if the scholar is up to date, that horrible redneck vision that is Holy Terror. The (US) mainstream, or what is considered as such, is centered around fan worship to the extent that “comics” seem to have become synonymous with “superheroes” and, by implication, anything not superheroes is deemed off-mainstream. But superheroes. Aren’t. Comics. They’re not even a genre, but tucked somewhere within the pulp genre, which, in its heyday, spread from dime novels to radio and cinema periodicals. Pulp settled into pop culture, and devolved into IPs, meaning in this case industrial properties; there is nothing intellectual going on in that department. Yet I’d hazard that Chris Ware, David Mazzucchelli, Art Spiegelman, Craig Thompson, and Charles Burns really fit as neatly in the mainstream bracket as the the contemporary fantasies of superheroes. Of a different kind, or sphere, certainly, but I’m not going to question the financial or editorial savvy of Big Six publishers like Random House. That “comics” become interchangeable with a cultural meme is just further sign that the already bent and spent term has outstayed, outlived, and out-welcomed its welcome. Looping back awkwardly to my attempts at definitions from the beginning; while our concept (or image) of “comics” may be well-rounded, diverse, and panoramic, the language we use to talk and even think about them is not a razor-edged vocabulary — rather, it has been dulled down to a blunt instrument by slipshod habits and flock mentality. I don’t claim originality, it’s hardly the first time the subject is brought up, and I don’t offer any solutions. Until somebody has a Eureka experience, and manages to have the new term stick. Until then we’re stuck with lame old “comics,” but instead of backing away from neologisms like “graphic novel,” we should just embrace them as non-qualitative, metaphoric descriptions that may open up new meanings and interpretations. And qualifying our terminology about different expressions within the form doesn’t do any harm, either. Still, I do think we should get the comedians to call themselves “jokers.” Unless DC has that term trademarked for their Bat-franchise. As I contemplate what to write for Hooded Utilitarian every month, I find certain images float into my head on a regular basis. These are the comics I grew up with, and the comics I loved, despite the fact that the art quite often was cringeworthy, the writing was often excruciating and even the concepts were frequently embarrassing to consider. Nonetheless, these are the comics I think about the most. These were comics I bought with my meager allowance, off the spinner rack at the local newstand and everything, just like any stereotypical 70s comic reader. Frequently, even when I was collecting them, I thought they were trash, and it was my love of awful things that kept sending me back to buy these truly dreadful stories, until the comics companies killed them out of pity. Some of these are actually quite good, but that wasn’t why I liked them. ^_^ The key to enjoying the Defenders was to realize that each and every one of the individual members was significantly broken in some way and when they joined together to fight as a team, those problems were magnified, rather than minimized. In my memory, more of the story was taken up with them arguing with one another than ever effectively handling any problem they faced. The Defenders became the home for all drop-out dysfunctional heroes who found it hard to play well with others, or who had argued with their real team and needed somewhere to go on a sulk. My favorite character was Valkyrie (oh gosh, I’m sure that’s a total shock) but not because she was just a female warrior. She was a female warrior from Norse Mythology – that totally did it for me. In an early expression of cluelessness about feminism (that has now become so extreme that comics journalism is replete with articles and commentary on it) Val couldn’t hit other women, but happily beat the crap out of male chauvinists, which were, not all that surprisingly, all males, since obviously feminism=man-hating. To be fair, most of the men Val dealt with were pretty chavinist, and all the men were clueless. This does not appear to have changed much in recent years. In high school, I discovered another deep love for a crappy comic. This time it was a retro look at the days when we were the good guys and the Nazis were the bad guys. The Invaders represented the Allies (well, the Allied countries and Submariner, because apparently the Nazis had it out for Atlantis too.) I had this cover inside my high school locker. You’re probably assuming it’s because I found the idea of a leather-clad, giant female warrior physically attractive, but actually you’d be wrong. My love for this cover has nothing to to with Krieger Frau herself, or the defeat of her and Master Man by the Invaders. My love of this cover has everything to do with a massive multi-media cross-over fanfic I wrote for about three years with a friend in high school. Krieger Frau just happens to looks a lot like the main bad guy in that fanfic. When I look at this cover, I see Snap Bar. Nonetheless, there was joy to be found in the morality play that was a look at the “good old days” of World War II. There is a freedom in knowing that we were right, and someone else was wrong and there were no questions about the ethics of clobbering bad guys. This series really stands out for the inexplicable use of sentences written backwards as magical spells by the scop (who, in this series is a Druid-like wizard rather than a story-teller.) “Happy Birthday Caroline” becomes a Lovecraftian incantation “Enilorac Yadhtrib Yppah!” Surely I wasn’t the only one to notice? There were so many things wrong with this series, on every level – indifferent art, incomprehensible story, that my reaction of loving it for its awfulness seems completely appropriate. As I say, I love my awful comics. But there was one, finally, that I had to genuinely say was the absolute worst comic I ever read. It was killed at 13 issues, for which I was immensely thankful. Even I don’t know why it was created, except as a pathetic way to recreate the popularity of Spiderman, using all the wrong elements. Spiderman, you may remember, was a nebbish. He was a freelance photographer and a college student. He was a skinny, dorky guy. When the spider bit him, he did not suddenly become cool and suave – he was now a super-powered dorky guy. He cracked jokes to cover the fact that he was terrified. He now goes from dorky kid to cool dude in a matter of weeks, but that transformation took decades. In the 80s, he was still a dorky guy, a milquetoast by day, joke-cracking half-competent superhero in his free time. So Marvel, cognizant that this kind of character had a readership, decided to try again. They created The Man Called Nova. I know they rebooted Nova in the 2000s, but they really laid the dorky loser on with a trowel the first time around. If you have never read the original Nova, and want to see how bad a comic can be, see if you can find a copy and read this. The main character, Richard Ryder, has all the awkwardness of Peter Parker, without any of his sincerity or charm. He’s supposed to a science student (I might be wrong in remembering it as physics) but shows no understanding of anything. The premise is similar to that of The Greatest American Hero, except that instead of losing the instruction booklet, Richard is given his suit by an alien and has to get used to the thing. The first several issues follow him picking fights with street punks. When he first encounters super-powered villians, he fails spectacularly. Maybe it was just the time and place, but when Nova wrapped up, I set it aside with a sense of relief. Horus and Set fight one-on-one, while Thor protects Isis and Jane. Ultimately it is the human, Jane Foster, who awakens Odin from his trance, and so Horus is able to cast Set into the abyss of space and rescue his father, thus returning balance to the universe. Now this is what comic books are all about. A few years later, when I ran into Margot again, she had just published the first volume of her book Hookah Girl and Other True Stories. I read the first volume and have since been giving it away to people as an example of a voice that needs to be heard and a talent that needs to be enjoyed by as many readers as possible. I am quite literally in the habit of buying her book to give it away. One of those gifts gained Margot a short write-up by Brigid Alverson on Robot 6. Brigid writes: [Hookah Girl] a memoir of growing up as a Palestinian Christian, within the immigrant community in the U.S., as well as a meditation on all the contradictions and labels that come with that identity. Dabaie starts the first volume with a set of paper dolls that embody each of those stereotypes‹Muslim girl in full hijab, suicide bomber with vest full of explosives, I-Dream-of-Jeannie seductress, starving artist. The stories touch on things that are familiar to immigrants in general — scary relatives, peculiar customs, native foods — but there is also an interesting comic about Leila Khaled that presents her as an interestingly complex individual. This book left me wanting to see more, and I hope there is a full-length graphic novel in the works. If there isn’t, there should be. Today it’s my pleasure to introduce you all to Margot and her work. Erica: Let’s start with the obligatory introduction. Margot: I grew up out in San Francisco, dabbled in drawing for a long time, and decided to move to NYC in order to strike a match under my butt. For the past couple of years, I’ve been working at a museum while attending graduate school (for illustration). I also freelance and teach art- and comic-related workshops. It’s a busy time for me right now, very productive, and I like it that way! E: What was your motivation for The Hookah Girl and Other True Stories? Two different threads led to the creation of The Hookah Girl: One is that I got a lot of “you should make a comic about this” comments from people who heard some of the stories that I ended up putting in the books. Tom Hart and Leela Corman were especially assertive about this, which I appreciate now. The second thread stems more with my aggravation towards how Arabs are generally portrayed in the media and the public perception of them. I was very good at not paying much attention to the bad rap, and managed to just completely tune it out for a really long time. But then, 9/11 happened and it became impossible for me to ignore it. I had friends telling me to not let on that I was Palestinian so that I wouldn’t be discriminated against, and I think that really hit home. Of course, my friends meant well, but it was difficult to swallow that I now lived in a place—In the US, no less!—where some people gave a crap that my father was born in Ramallah. I had my own little “Arab Spring” throughout the years and one of the results is my comic. I’ve nicknamed The Hookah Girl “Arab 101” because I ended up writing with a non-Arab audience in mind. I wanted to highlight that, while my family and some of their practices are not “western” and may be distinct, they are not any more or less distinct than any other family. The positives and negatives are not all that different from any variety of cultures, and they just are. I get the greatest thrill when someone comes up to me and tells me that my grandmother reminds them of their French grandmother, or Nigerian uncle, or Korean mother. This is exactly the kind of reaction I wanted—that we all have a Teta in our lives. E: How has the reaction to Hookah Girl been? As a person of Jewish descent, it’s been hard for me to watch the vilification of everything Arab in some of the media. Like, haven’t we learned anything in 2000 years, seriously? I can’t imagine that you haven’t gotten at least some negative feedback. M: The comic has been received fairly well. I have had some unfortunate instances where people did not agree with the political implications behind calling oneself a Palestinian (because just using the “P” word can be a political act) and dismissed it for that alone. I’ve also had people admonish the work because I mention some negative aspects—namely, my father’s sexist tendencies and my exploration of Leila Khaled, a 1960s terrorist. The positives outweigh the negatives, though, and I absolutely feel like making the comic has been worth it. The connection I have achieved with people is the whole point, really! E: Well, for what its worth, it totally connected with me. You’re very outspoken about what you think, which I just love. What is the one panel you’ve done that best expresses yourself? E: Hahah, I can totally see you like that. Who are your artistic influences, comic or otherwise? M: Firstly, I’m really influenced by “folk” art. I especially love work that is flat and very graphic—patterns on textiles, tapestries, manuscripts on vellum, murals, and the like. Some of the artists who I actively look at are Rembrandt, Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, Lorraine Fox (I can thank Murray Tinkelman for introducing me to her work!), Trina Schart-Hyman, J. C. Leyendecker, and Yoshitaka Amano. In regards to comic influences, I’ve felt strong connections to Naji al-Ali and lots of older manga—especially anything made by CLAMP in the 1990s (RG Veda takes the cake), Masamune Shirow, and Rumiko Takahashi. E: The manga influences really show in your story-telling style. You write a webcomic “He Also Has Drills For Hands,” where did you get that name? Tell us about the comic. M: I originally started writing HAHDFH as a self-imposed exercise. I felt like my work was getting too precious and I wanted to publicly make a large body of work. So, I chose to leave the strip’s subject matter totally open (a lot of them deal with funny little everyday occurrences, but I still have my occasional Really Random Strip) and I draw them in a small sketchbook that’s really portable, so I can draw them while I’m out running around and doing my thing. They’re a lot of fun to make and when I started out, I was drawing one a day. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to keep that schedule up—grad school does that to you—so they’ve been knocked down to three strips a week. The title alludes to one of my really early strips in which I talk about my childhood crushes. One of them is a robot named Crash Man who is a character from the video game Mega Man 2. The title was a line in the strip, because Crash Man does, indeed, have drills for hands! My kid self managed to look past the drills. E: We’ve reached the obligatory “What are you working on right now?” question. So, what are you working on? M: I’m currently in the research/very, very preliminary sketching phase for a historical-fictional graphic novel. It’ll take place in 7th-century Sogdiana, which was in modern-day Uzbekistan. E: We talked about this a bit at New York Comic Con. It sounds pretty fantastic. M: It will be chock-full of Silk-Road goodness. I’m going to put up a website about this project soon! E: I know I’m looking forward to reading it. Margot, thanks so much for your time today! M: Thank you! I hope you’ll all check Margot’s work out at Margoyle.net – and let me know what you think here.

________

________

For all HU posts on

Posted in Blog, Satire and Charlie Hebdo Roundtable, Top Featured

|

Tagged comics, Kim O'Connor, Satire and Charlie Hebdo Roundtable

Prehistory of the Superhero (Part Seven): Reign of the Superman

Art by Joe Shuster

– Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American NietzscheSee you in the Funny Papers

Art by Roy Crane; click on image to enlarge

This opened the way for such classic adventure series as Terry and the Pirates, Prince Valiant, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy.Art by Phil Davis (1906-1964)

Mandrake has been the springboard for subsequent magician superheroes such as Ibis the Invincible, Dr Strange, or Zatara. Sometimes the imitation verged on plagiarism: witness Zatara:

Art by Fred Guardineer

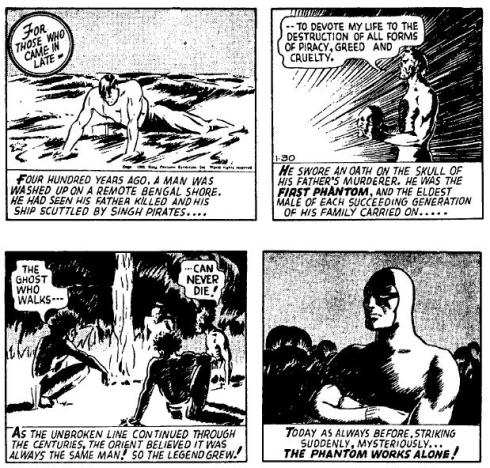

Falks’ other classic superhero creation was the Phantom of Bengal (1936).

The Phantom had an original backstory: Kit Walker was the 21st Phantom in a lineage stretching back to his ancestor in 1516. By adopting the same mask and costume generation after generation, the Phantoms created the legend of an immortal fighter for justice:Art by Ray Moore (1905-1984); click on image to enlarge

The Phatom‘s costume pioneered several of the visual tropes associated with superheroes ever since: form-fitting top and tights, with the elegant innovation of underpants worn on the outside; a skull-hugging hood; and a mask with blanks hiding the eyes. All he lacked was a cape — which deficiency Mandrake supplied. Compare the Phantom to such later superheroes like Batman and Captain America, and it’s obvious how much the latter owe to Falks’ design.

All in Color for a Dime

Funnies on Parade was devised chiefly as a way to keep Depression-idled printing presses busy. It was never sold, but used as a promotional giveaway by Procter and Gamble; everybody thought there was no money to be made selling what came free with the daily newspaper.

Cover illustration by Jon Mayes

The newsstands were soon flooded with comic books. It’s not hard to understand their appeal; in our age of i-Pads and portable television, we have to remember that back in the 1930s immersive visual entertainment was limited to movie theatres.

But far from this publishing sideshow, 1933 is a year chiefly remembered for a dark and world-changing occurrence on the other side of the Atlantic: on January 30, President Paul Von Hindenburg appointed the leader of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, Adolph Hitler, the Chancellor of Germany.Hoch der Uebermensch!

Illustration for the 2nd Congress of Eugenics (1921). Click image to enlarge.

Eugenics is an ideology that calls for the preservation or improvement of human genetic stock by encouraging “superior” individuals, and discouraging “inferior” ones, to breed. From the vantage point of the 21st century, after a hundred years of horror and suffering inflicted by such ‘scientific’ racism, it is hard to wrap our heads around the idea that this was once considered a humane and socially progressive idea; yet champions of eugenics included such forward-thinking persons as H.G.Wells, Margaret Sanger, George Bernard Shaw andSydney Webb.

German propaganda poster, 1942. Note the contrast between the calm, strong “Uebermensch” German soldier and the defeated, multiracial French prisoners in the background.

(Before crossing the Atlantic back to the USA, let me repeat that Nietzsche himself was, contrary to popular modern conception, not at all a proponent of the sort of ruthless evolutionary pruning that characterised social Darwinists and eugenics enthusiasts:Man of Steel — and of Paper

click on image to enlarge

This Superman was an evil tyrant with psychic powers. Siegel, later in life, recalled how the word and concept of a superman was much discussed at the time, in tandem with the rise of Naziism in Germany. Both Siegel and Shuster were Jews; this evil ur-Superman likely reflected alarm over growing Nazi power.art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

The above illustration shows another strong influence on Superman’s genesis, the pulp hero Doc Savage. Consider the below house advertisement for Doc:click on image to enlarge

Now began a five-year effort to sell the strip. It was turned down time and again by the syndicates. One editor commented: “The trouble with this, kid, is that it’s too sensational. Nobody would believe it.” Bell Syndicate told them, “We are in the market only for strips likely to have the most extra-ordinary appeal, and we do not feel Superman gets into this category.” United Features said that Superman was “a rather immature piece of work.” art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

This act of destruction cleared the way for a new version. There was a new outfit, obviously inspired by newspapers’ The Phantom and by circus performers. As Shuster noted, they had created a “kind of costume and let’s give him a big S on his chest, and a cape, make him as colorful as we can and as distinctive as we can.” This showbiz instinct was tremendously prescient. The image of Superman is recognised the world over — a marvellous branding success — and has been imitated by countless superhero characters up to the present day.Joe Shuster at the drawing board, with Jerry Siegel hovering; click on photo to enlarge

Finally, the two creators were able to place the strip with Max Gaines at National Allied Publications — the future DC comics. It was looked on almost as filler material — editor Vin Sullivan didn’t have enough strips to round out Action Comics 1. Still, Superman was splashed on the cover — a cover that almost went unused because Gaines felt it was too silly:art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

art by Fred Guardineer

The comic came out on April 18, 1938. It was an instant sellout. The age of the superhero comic book was born — and continues today, in a much-etiolated, decadent form, totally dominating popular comic books — to the point where superhero comics are actually termed ‘mainstream’. (Famously, Siegel and Shuster saw the merest trickle of the ocean of money Superman was to generate.)

The hero of Gladiator, Hugo Danner, exhibits powers identical to those ofSuperman‘s in his first appearances: herculean strength, bulletproof skin, the ability to leap great distances. Danner got his power as a result of his scientist father’s attempt to replicate the proportional strength of insects; now read this early presentation of Superman, with a note at the end on his power:art by Joe Shuster; click on image to enlarge

Wylie, in a 1963 interview with science fiction historian Sam Moscowitz, claimed that Superman was plagiarised from Gladiator, and that he’d threatened to sue Siegel and the publisher in 1940.Next: Inventory and Conclusion

Sequential Splortch

______________

—cover flap of Frederic Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent

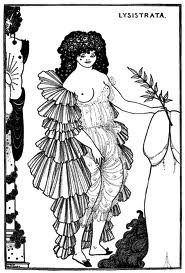

Lascivious, decadent Europeans, inspired by such hot-and-heavy Japanese print-making, erected sophisticated fantastic visions of their own. Here, for example, turn-of-the-century Brit Aubrey Beardsley makes a subtle phallic reference.

Porn actually played a vital part in the survival of one of the most respected independent comics publishers. Fantagraphics — whose catalog includes Dan Clowes and Los Bros Hernandez — was poised to go out of business in the early 90s. It was saved in part by the launch of its adult-oriented Eros line. It’s kind of funny to think that there would be no Chris Ware as we know him without concupiscence and gushing bodily fluids (though that’s true for all of us, I suppose.)Small Fish, Big Pond

Comics Sales

DVD Sales

Music

Books

Nothing You Didn’t Know

Like Language to the Slaughter

Comics I Like Despite Themselves

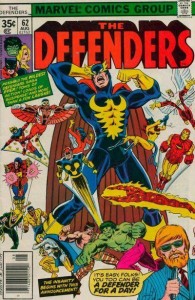

The Defenders – I liked this series because they were total losers as a group. “B”-team doesn’t cut it. Individually, they were only partially effective as superheroes, as a team, they were a joke…which was mostly the plot of the series, in between some personality switching, possession and, of course, fighting.

The Defenders – I liked this series because they were total losers as a group. “B”-team doesn’t cut it. Individually, they were only partially effective as superheroes, as a team, they were a joke…which was mostly the plot of the series, in between some personality switching, possession and, of course, fighting.

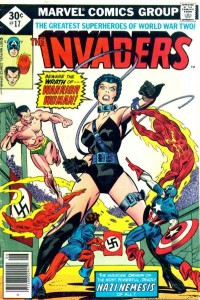

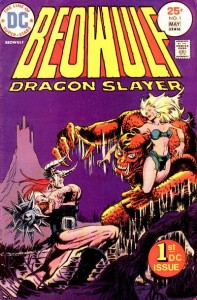

One of my prize possessions is a truly awful short-lived series by DC that was supposed to tell the Beowulf story, Beowulf Dragon Slayer. It didn’t. It strapped Beowulf into an uncomfortable-looking Michelin Man-esque costume, made of belts, and tortured a simple story beyond its own ability to tolerate. Many years later, I brought this series into my graduate class on Beowulf, and laughed while my classmates boggled that someone could get it so wrong.

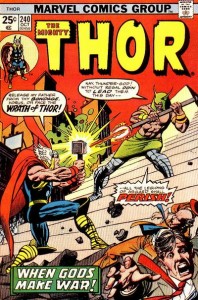

One of my prize possessions is a truly awful short-lived series by DC that was supposed to tell the Beowulf story, Beowulf Dragon Slayer. It didn’t. It strapped Beowulf into an uncomfortable-looking Michelin Man-esque costume, made of belts, and tortured a simple story beyond its own ability to tolerate. Many years later, I brought this series into my graduate class on Beowulf, and laughed while my classmates boggled that someone could get it so wrong. The one truly awful storyline that I adore with all my being from my American comics collecting days was when the ancient Egyptian gods kidnap and brainwash Odin into thinking he’s Osiris, in order to defeat Set. This storyline hit me in my weakest of weak spots – mythology as a hook. Could there really ever be anything sexier than Horus and Thor fighting on a pyramid, in order for Thor to retrieve his father? Yes, yes there could. There is a sequence mid-arc, where Horus and Thor fight together, on a giant causeway in space, against hordes of skeletons sent by Set, god of death (do not attempt to correct Marvel, they do not care about accuracy) while Jane beseeches Odin/Osiris to help his son.

The one truly awful storyline that I adore with all my being from my American comics collecting days was when the ancient Egyptian gods kidnap and brainwash Odin into thinking he’s Osiris, in order to defeat Set. This storyline hit me in my weakest of weak spots – mythology as a hook. Could there really ever be anything sexier than Horus and Thor fighting on a pyramid, in order for Thor to retrieve his father? Yes, yes there could. There is a sequence mid-arc, where Horus and Thor fight together, on a giant causeway in space, against hordes of skeletons sent by Set, god of death (do not attempt to correct Marvel, they do not care about accuracy) while Jane beseeches Odin/Osiris to help his son.Interview with Independent Comic Artist Marguerite Dabaie

A number of years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of young artists at the Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art. It was spectacular evening, and I’ve made a point of keeping in touch with several of the talented young people I met there. A few years later, at the annual MoCCA event, I ran into one of those young artists, Marguerite Dabaie. She handed me a self-published comic about transvestites during the Weimar Republic. I was instantly hooked by her personal style of story-telling that communicated emotion, without beating you with it.

A number of years ago, I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of young artists at the Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art. It was spectacular evening, and I’ve made a point of keeping in touch with several of the talented young people I met there. A few years later, at the annual MoCCA event, I ran into one of those young artists, Marguerite Dabaie. She handed me a self-published comic about transvestites during the Weimar Republic. I was instantly hooked by her personal style of story-telling that communicated emotion, without beating you with it.