A while back Isaac Cates posted an analysis of a panel from Ghost World over at The Panelists. Since the Panelists is sadly going to fold shortly, Isaac re-posted it at his own place.. Anyway, Isaac also posted comments from the post, including some of mine. But not all of them…so I thought I’d collect them here. And what the hey, I’ve reproduced some comments from others on the thread too so this seems a bit more coherent.

______________

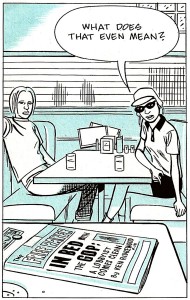

So to start, here’s Isaac’s (abbreviated) take on the a panel from Ghost World.

At the beginning of the chapter, Clowes reveals Enid to be deeply clueless about the outside world in a way that rewrites a lot of her seeming savvy in the previous chapters. Up to this point, Enid has been cool, positioning herself against the stupid, the pretentious, and the lame: “I just hate all these obnoxious, extroverted, pseudo-bohemian art-school losers!” (Is that Enid talking, or Lloyd Llewellyn?) But then the change-up:

Enid’s fun to hang out with, but how seriously can we take a high-school graduate who doesn’t know what the G.O.P. is, or what it would mean for a lobbyist to be in bed with them? Don’t we have to think of her as uninformed, immature, and a little lame? This is the panel that gets us ready to think badly of Enid’s prank on “Bearded Windbreaker.” It’s also the moment, at least in my reading experience, when we start looking at these girls from the outside, as characters, instead of seeing the semi-grotesque world through their eyes. In other words, this is the panel in which Clowes moves away from Lloyd Llewellyn and Like a Velvet Glove territory and starts to make David Boring and Ice Haven possible.

I replied to Isaac and to other folks on the thread:

I read it that Enid knows what the headline means too. And in that reading, of course, it’s Isaac, not Enid, who’s insufficiently hip and a little clueless, yes? (Though, of course, in Isaac’s reading, it’s me who is unhip/clueless.)

I think trapping/implicating the reader in these questions of knowing/not knowing, hipness/not hipness, and the subsequent arguments about who is more moral and who is more superior is an important part of what Ghost World is about. In general, I find those questions tedious and irritating, which is one of the (many) reasons I don’t care for this book.

Jeet then quotes Charles Hatfield’s comment.

Noah: you’re not engaging with what Charles actually wrote above. As he says, “Seriously, the moral arguments in Ghost World are not reducible to who’s hip and who’s not. There are questions of empathy and responsibility there that exceed, I bet, even what Clowes expected from the work when he was midstream.” That’s a serious reading of Ghost World which you have to grapple with. you can’t just repeat your earlier point about the book just being about “who is and is not a sufficiently or overly knowledgeable hipster.” To simply repeat your earlier point when it’s been challenged in a serious and convincing way is to write criticism that is, to borrow a phrase, “tedious and irritating.”

I’m not writing criticism! I’m engaging jovially in a comments thread.

I don’t want to derail the thread with a grudge match. You want to engage in a knock-down drag out, come over to HU and talk about Human Diastrophism. We’re waiting for you!

Oh, all right. Sigh.

I don’t find the questions of empathy and moral responsibility Charles is talking about either engaging or enlightening. As I’ve written about the book elsewhere, what I mostly get from it is an older male creator acting out his attraction/repulsion for younger girls. I think that fits this panel quite well. The girls are looking off panel at the reader/author, whose paper it is. The paper is about the Grand Old Party (coded old and surely male) performing metaphorically sexual acts. Clowes has Enid ironically refusing to understand the headline — a sexual disavowal, which actually means she understands quite well this headline about perverse sex with grand old men. The knowledge/not knowledge binary is a tease and a provocation; the moral experience Isaac articulates in which we are able to feel superior (and/or possibly inferior) to Enid is part of the (sexualized) satisfaction we (the grand old party) get in pretending that Enid knows and does not know us.

Happy?

Damn it; hard to disengage when I get started. I wear that “tedious and irritating” badge proudly….

So just a couple more notes. First, I don’t think this is something Clowes is unaware of. He picks his details carefully; the Grand Old Party is really not just a random choice.

Second — in this reading, Clowes emphatically gets the laugh on Enid. Enid is saying she doesn’t understand the headline in order to show she understands it; she gets the stupid metaphor. But the trick is, that stupid metaphor isn’t just a random paper lying around; it’s a snide sexual remark implicating Enid which has been placed there by Clowes. Enid gets the diagetic point, but not the extra-diagetic point. She’s attempting to assert her control and wisdom, but Clowes shows us she’s just his cipher. In this way Isaac gets the details wrong but the essence right; this is a panel which sneers at Enid for her lack of sophistication. I don’t find that particularly morally insightful or uplifting though.

All right, I’m really done. Sorry about that.

@Noah. “what I mostly get from it is an older male creator acting out his attraction/repulsion for younger girls”: this is a pretty good example of “the intentional fallacy” in action. I don’t think its very fruitful to judge works of art by what the author’s presumed motives are. In fact, I don’t even think it’s possible for anyone (even Clowes) to know what the motives of his art art, or what the motives of any art are.

The issue of “moral questioning” that Charles raised have to do with the friendship between Enid and Becky, and also how the two girls treat other people. This is something that can be discussed by looking at what Clowes wrote and drew. It doesn’t really contribute to the conversation to speculate about Clowes motives, unless by chance you are a telepath. If you are a telepath, then tell us and continue to enlighten us about the secret, ulterior motive of artists. On the other hand, if you are a telepath, you could use your power in more frutiful ways, perhaps by uncovering government and corporate corruption.

Isaac adds:

Jeet:

I’m not really interested in whether Clowes personally thinks Enid is hawt, but I find that I am interested in at least one aspect of an author’s perceivable psychology (intentional or not): as his interests and ideas shift, the themes of the works shift. If I find myself responding more to the ideas in David Boring than in Like a Velvet Glove, and I know they’re written by the same person, I want to see when those new ideas started to develop.

Noah seems to be caricaturing those ideas as merely an older (not yet middle aged) cartoonist pining for teenage indie tail and then rejecting the notion of jailbait.

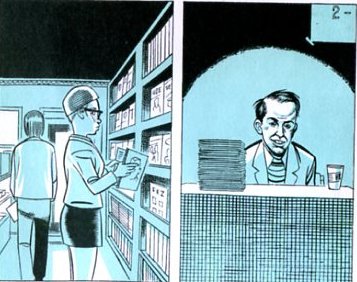

For me, or at least in my reading of Ghost World, it’s about more than (or less than?) simple attraction to scornful ugly-cute teenage girls: instead, it’s about Clowes as a writer moving out of a period of personal grotesquerie and universal satire (as in “I Hate You Deeply”) and into a period of social observation, where he becomes interested in writing characters.

There might be a grain of truth in Noah’s lampooning—remember the way that Clowes has Enid show up admiringly at a zine-store signing in “Punk Day,” then draws himself looking like a seedy dork—but I think the real crux of the matter is artistic development beyond teenage scorn and hipster one-upmanship. This is a lot closer to Charles’s notion of ethical stakes than Noah is allowing. And I think Clowes makes that turn in “Hubba Hubba.”

Jeet:

@Isaac. I find your reading of Ghost World as a liminal work in Clowes’ oeuvre to be compelling and persuasive. But seeing Ghost World as being thematically focused on Clowes’ own evolution as an artist is a bit different than the type of argument Noah is making, which is that we can divine Clowes’ motives for doing the type of art he does. Your reading of Clowes is based on looking at the trajectory of his career, on looking at the comics itself. I think Noah’s approach is based on some sort of pretense to telepathic powers.

Isaac:

Well, you could call that a pretense to telepathic powers, or you could call it Freudian criticism…

As I said, though, I don’t think that “Did the cartoonist want to jump these fictional characters?” is the most interesting question we could be asking about a text.

Me:

I like that your accusations of intentional fallacy are built on intentional fallacy. You presume I started from an idea of what Clowes was doing and read back into the comic. In fact it’s signals in the comic that led to my reading. “Clowes” figures in the text as an author function. He does it very insistently — he’s even in the book, as Isaac says. He’s in that panel; it’s his paper (and the reader’s too, quite possibly). I don’t know what Clowes had in his head, of course, but I know how he figures himself in the text and I can do a reading based on that.

You seem to think that you’re performing some sort of advanced literary technique by refusing to think about the self-reflexivity of the text. That’s characteristic; you tend to be fairly uncomfortable with readings that aren’t straightforward. But Clowes is very much a pomo writer; he’s playing games with the intentionality you want to put off limits.

I don’t think Clowes wanted to jump the characters necessarily, or only, by the by. It’s about inhabiting them too. Sadism is not just lust; it’s control.

There are lots of older men in Ghost World, incidentally. Clowes himself shows up, but there are various other figures wandering around the edges. And of course Enid’s name is Clowes’ name. Seeing her as and Becky as doppelgangers (doppelmeyers?) is hardly a counter-intuitive reading.

But you haven’t done a reading yourself, Jeet, serious or otherwise. If you want to take on the panel and respond to my criticism (other than with ad hominem petulance) it seems like you’d need to try to deal with the following: the reason that that title was chosen on the newspaper; the reason the panel is framed so as to suggest that the paper is the reader’s (or Clowes’); the role of knowledge in the panel, and how it accounts for both Isaac’s reading (Enid doesn’t know) and the other readings here (Enid does know) — and ideally also you should account for the hints throughout that Enid and Becky are Clowes.

I presume you’ll just indulge in more indignation and then punt, but I’ll live in hope.

Isaac, in terms of what’s more interesting in the text, morality or jumping bones. Do you really see Clowes’ moral vision as especially serious or insightful compared to folks who actually care about that stuff — George Eliot, Tolstoy, Jane Austen, even Dickens? It all just seems pretty thin gruel by those standards to me — the characterization is thin, the “morals” such as they are boil down to “don’t be a prick” — I just don’t see it as an especially powerful or interesting moral vision. Do we really need someone to tell us that it’s cruel to prank call people? I mean, this isn’t Lydgate being tempted here. The moral questions aren’t what’s interesting; what’s interesting is watching Enid be taught A Lesson.

To me, that’s because the energy of the book is not invested in morality as morality; rather it’s invested in morality as a lever of desire and power, about the experience of condemnation and wanting to be condemned. That’s why you’re reading of this panel isn’t really about morality. It’s about knowledge, and it’s about contempt. And about Clowes, of course.

Isaac:

I don’t think I’m trying to compare Clowes to Tolstoy here. I’m comparing “early Clowes” to “later Clowes”—and noticing a difference that has to do with the position (moral, ethical, social, whatever) of the satirist or the satirical impulse.

Early in Ghost World, as in the Lloyd Llewellyn shorts, the satirist is impervious; beginning in “Hubba Hubba,” making fun of people starts to seem like a sign of personal insecurity and even a certain sort of naïveté. I think that’s an interesting development.

Me:

Well, fair enough. I think comparing to Tolstory (or the Wire, or whatever) is kind of interesting, but no reason why you should have to, of course.

Rob Clough:

To tie Isaac’s claims back into what I said, Ghost World represents the turning point between unfettered, unimpeachable satirist and a more self-aware artist and person understanding what their constant sneering represents. I agree 100% that Enid is a Clowes stand-in, but the issue is not even controlling a young girl, but rather exploring and expressing the understanding of how much self-loathing she (and he) possess at that point in time. Clowes drawing himself in as a grotesque, pathetic toad isn’t just a good gag, I would argue, but an expression of his own self-loathing.

Enid being taught a lesson regarding pranks isn’t a simple control/corrective of a young female, it’s Clowes castigating himself for indulging in the pleasures of simple cruelty as a way of coping with alienation.

Lastly, while I agree with Isaac that Clowes’ character work became much sharper starting with Ghost World, I would argue that nearly every one of his characters represented some autobiographical aspect of his life, personality and/or desires. Even with all of the pomo deflections, Clowes’ work is deeply personal.

Jeet:

I think Clough pretty much hits the nail on the head in sharpening the point Isaac originally made that Enid is a way for Clowes to reexamine his earlier artistic practices. I’d go further and note that their is a contradiction between saying that Enid is Clowes’ alter-ego and saying that he’s using her as a punching bag to work out his revulsion/attraction to young women. Yet the same critic can hold these two positions simultaneously.

Me:

Hey Jeet. Not a contradiction.

Sadism is about control. As such, it’s often about fantasies of actually inhabiting or being the other person. So imagining someone as your alter ego can be a way to inhabit them and destroy them. Basic rape fantasy. And sure, it seems logically contradictory if you’re writing an algorithm…but human beings and their fictions aren’t algorithms (unless you have more faith in the Turing Test than I do, I guess.)

Anyway — truce, maybe? I really don’t need to be mad at anybody for liking Ghost World. I don’t agree, and I in general don’t see art the way you do, but it’s not a big deal. It’s fun to talk about the differences, and I appreciate you getting me to figure out my reading of that panel more explicitly.

Rob, you’re point that Clough’s moralism is directed at himself is interesting, and I think it’s certainly part of what’s going on. But why externalize that self as a young girl? Self-loathing and misogyny aren’t mutually exclusive, surely. You can hate yourself for loving and love yourself for hating all at once. And the gross, pathetic toad who is controlling/watching/inhabiting the attractive young thing is a ubiquitous fantasy in itself. Self-loathing can be a pleasure too.

And I’ll conclude with a comment by Caro:

I think I’m hesitant in general about the “shift through time” linearity of your argument, Isaac. Ouevre questions aside, I didn’t find Ghost World to have nearly as linear a narrative trajectory as the shift you’re describing suggests — I read it in the Eightballs (long after their original publication) and it was very nested and recursive to me, with each episode covering very similar ground save very subtle, significant, changes as Enid matured. There were constant metaphorical returns as well — really a structural tour de force. (I was apathetic about it, actually, until I got deeply invested in disagreeing with Noah’s reading from our roundtable last year.)

I still disagree with Noah, but also with Jeet — there’s nothing contradictory about representing a character from both inside and outside. Although I don’t see the same objectification here that Noah does, I think the objectification that is there is of a piece with the identity crisis at the heart of the narrative — the blurring/confusion of self and other — “desire is the desire of the Other” — it is Freud playing the piano there on the back cover of Issue #17…

Thanks to Isaac again for starting this conversation. Revisiting reminds me why I’m really sorry that the Panelists is shuttering.