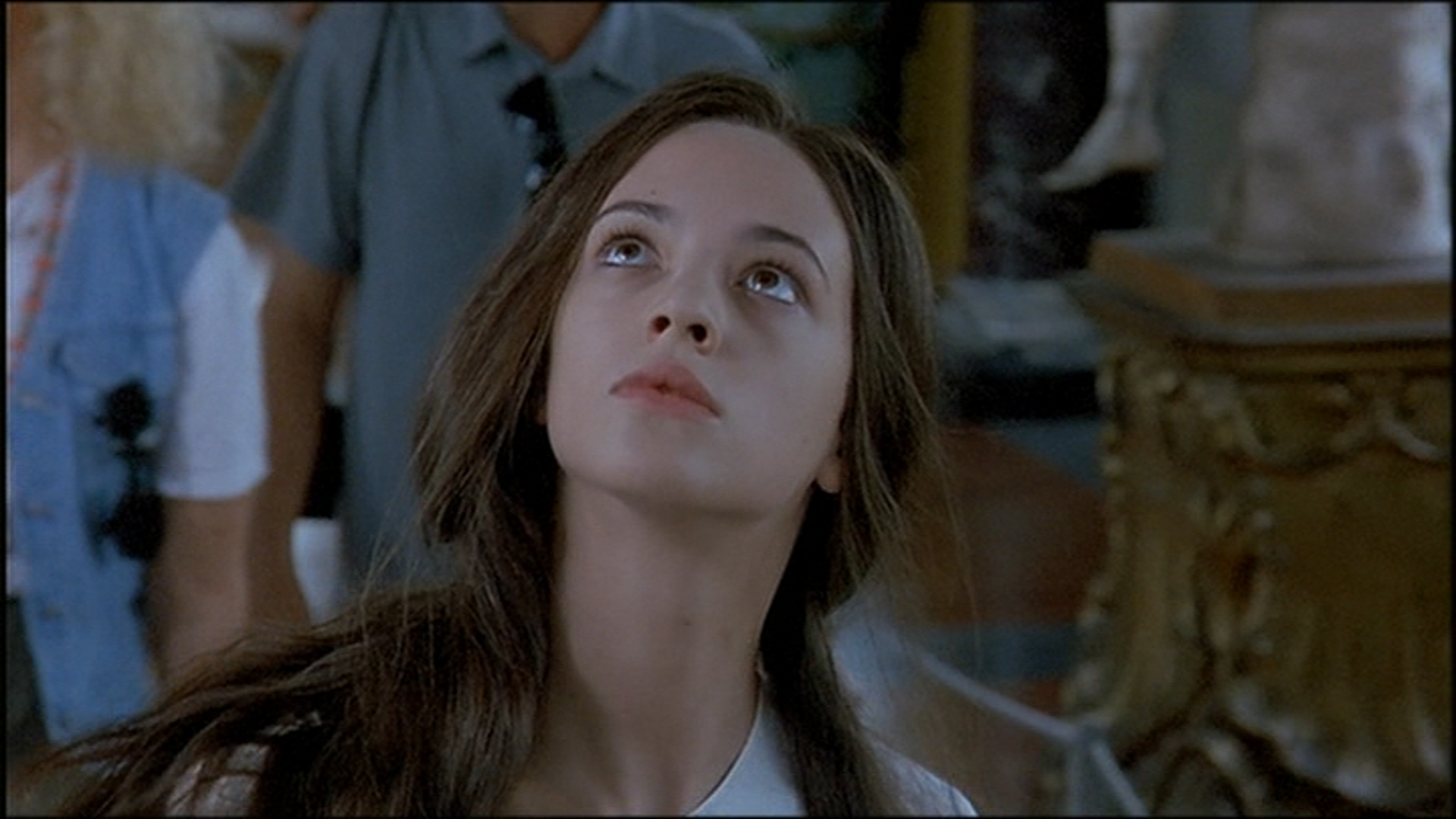

According to Andrew Cooper, you can read the Stendahl Syndrome as a winking parody of critical fears of horror movies. In the film, Detective Anna Manni (Asia Argento) is violently raped by a serial predator. The rapist manages to capture her because she suffers from Stendahl Syndrome—a psychological condition which causes her to be overcome, and even experience hallucinations, when viewing art. Anna, then, is the incredibly overly receptive viewer of critics’ nightmares; her whole view of reality is transformed by aesthetic experience. Little wonder, then, that the rape/revenge plot of the film she is in leads her to perdition. Morally censorious critics imagine that watching films causes violence; Anna, the overly sensitive viewer, observes her rapist and becomes him. She does manage to take her revenge, but after doing so, she becomes psychotic herself. Through the power of art, the detective changes to the murderer. End of joke.

There’s another, less ironic way to take the film, though. Most rape/revenge films are narratively linear, and set. You start out with a healthy, unmarked woman; she is abused, suffers, strikes back, and destroys her tormenter.

The Stendahl Syndrome scrambles this—not with the rather obvious chronological trickery of Irreversible, but through more subtly letting the emotional and narrative components of the story shift out of true. Anna begins to experience trauma when she goes to an art gallery, before she is raped. And rather than a singular event, the rape is reenacted; first by Anna, who begins to dress as a man, and then molests her boyfriend, and then by the rapist, who attacks other women, and then re-kidnaps Anna. Finally, Anna murders the rapist in revenge—but that doesn’t end the story. Instead, the narrative grinds on, with the rapist apparently back from the dead—until it turns out it’s not the rapist, but Anna herself who is murdering her own lovers and friends. The rapist is inside her, she says; being violated, and then enacting violence herself, has turned her into him. She becomes the abusive patriarch who assaulted her.

Psycho, and Hitchcock in general, seem like an obvious touchstone here; as in Hitchcock’s films, the movie world seems to gleefully conspire against the beautiful protagonist, creating switchback complications to destroy and humiliate her. But unlike in Hitchcock, the film affect is always, firmly with Anna, which means the complications don’t seem like trickery, but like grotesque unfairness. The movie even says, just about outright, that it is rigged against Anna; it is art itself which disorients her and traumatizes her before the rapist can.

Again, Anna’s susceptibility to art could be a meta-comment that art doesn’t actually work like this; a painting doesn’t make you hallucinate, a film doesn’t make you a murderer. But the antipathy of art within the film could also be an acknowledgement of the antipathy of the film itself—and, metaphorically, of the antipathy of the world outside the film.

Sexual violence and patriarchy aren’t neatly contained in a narrative of (provisional) redemption. Instead, they leak out everywhere. Anna is traumatized before she is traumatized; her rapist continues to haunt her not only after the rape, but after his death. The violence to her is not only real, but symbolic—and is so overwhelming that she can’t even separate the violence from her self. Her relationship to her own sexuality, and her own violence, is inseparable from what has been done to her—and what has been done to her isn’t just the rape, but the vision in which the rape occurs, which precedes it and enables it.

One of many false climaxes in The Stendahl Syndrome occurs during Anna’s second rape. She has been tied down to a bed, and the rapist, having finished his work, leaves to amuse himself in some other way before coming back to finish her. There’s graffitti on the walls of the chamber, and her syndrome kicks in, causing her to hallucinate. Her powerful thrashing allows her to free herself. She kills her attacker when he returns in an extremely satisfying scene. Art serves as inspiration for empowerment — the message of many revenge films which seek to uplift, whether Fury Road or Ex Machina.

But Anna can’t get out of the film. Once she has tied herself to the tropes of suspense and violence and patriarchy, she can’t undo the knots. If Stendahl Syndrome is a parody of the idea that aesthetics can corrupt, it’s also a parody of the idea that aesthetics can save and liberate. Instead, in the Stendahl Syndrome, art and life collaborate together to create a hierarchy from which there is no escape, a dream of violence that doesn’t end.