Caro asked me, as her go-to guy on things King Lear, to write up some thoughts for the Hoodlum Unitarian roundtable. I can therefore say with assurance that the key to understanding Godard’s 1987 King Lear, unlike most productions of the Shakespeare play, is Charles Bronson’s Death Wish 4: The Crackdown.

What, haven’t seen it? Fate has been kind enough to me that I can say the same. I’m thinking more about what it has in common with Bo Derek’s post-10 bomb Bolero, Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, the Raiders of the Lost Ark knock-off King Solomon’s Mines, and another movie I won’t even bother to name but whose Wikipedia plot summary begins: “A female aerobic instructor is possessed by an evil spirit of a fallen ninja…”

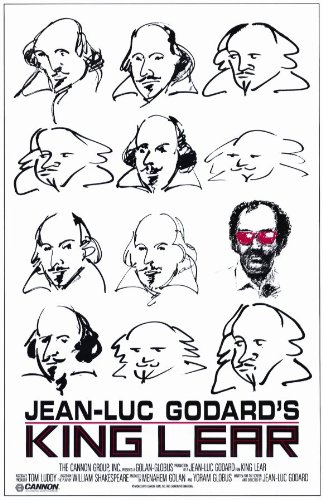

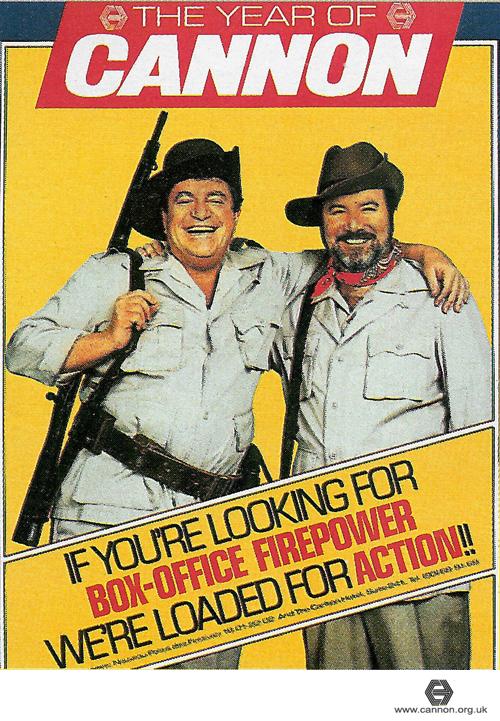

This collection of infinitesimally budgeted squeezings from tapped-out franchises all share a common source: the Cannon Film Group, in that period from 1979 to 1988 when it was owned by the Israeli duo Menachem Golam and Yoram Globus.

While Golam and Globus may have been schlockmeisters without peer, they were schlockmeisters with occasional cultural ambitions and/or pretensions. And near the end of their control of the Cannon Film Group, Jean-Luc Godard decided to take those ambitions for a joyride.

King Lear has, among all his other problems with the universe, a spotty film career.

At the moment, the text of King Lear is probably best known in Hollywood for being misquoted in a tattoo on Megan Fox’s back. (Lear Life Lesson: don’t get tattoos in parlors without internet access; the skin you save may be your own.) The first film version of King Lear predates sound, which means either Panto Lear or the world’s densest title cards. It was sixteen minutes long.

There have been some really good television productions — Laurence Olivier, Michael Hordern (my fave), Ian Holm, Ian McKellen, Orson Welles — but trips to the big screen have been rare. In my lifetime there’s been a Russian production under Grigori Kosintsev, and it’s inexplicable that I haven’t seen it; doubly inexplicable given that it’s got an original score by Dmitri Shostakovich. There’s the existential despair-fest of Peter Brook, milking every drop of downericity. Al Pacino has announced plans, and I’m pretty excited about it, but apparently now it is about as likely to get made as Atlas Shrugged: Part II.

And then there’s this thing.

Would you be surprised if I said that Godard’s take on King Lear was not exceptionally literal? That there’s probably more actual Lear in the 16-minute silent version?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybOhr-RtAas&feature=youtu.be

Before the opening credits, there is a recording of a phone conversation.

Godard: “Well… uh…”

Either Golem or Globus: “Let me tell in short, two sentences, my main concern.”

Godard: “Yes, of course.”

Either Golem or Globus: “My main concern is the concern of the company and the prestige of Cannon Group. Cannon has announced for a year and a half [at this point the cheerful baroque accompaniment skids into the ditch, as of someone pulled the phonograph plug] Jean-Luc Godard’s movie, ‘King Lear.’ It is not believed by many that the movie will ever be done. We are losing confidence. We are losing our name. I, I must insist that this movie, as promised, which was already postponed so many times, will reach the Cannes festival. This is my main concern.”

An unidentified but lawyerly voice on the other end of the phone says: “Okay, Jean-Luc, why don’t you respond to that.”

The movie is his response.

The film proper begins, actually, with a line about Norman Mailer: “Mailer. Oh yes, that is a good way to begin.” The line is delivered by, naturally, Norman Mailer.

Mailer, uncredited, playing a Very Famous Writer, has decided that King Lear works better if stripped to its essence. And its essence, as the Very Famous Writer sees it, is a Mafia movie: Don Learo, Don Kenny, Don Gloucestro…

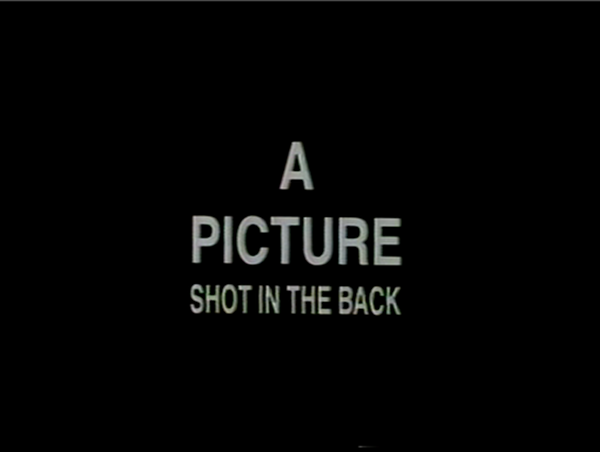

And then the movie starts over again: a different take of the same scene — Mailer and his daughter Kate, discussing his approach and then, for more context, reading the contract they signed with Godard. Intercut are a series of title cards, as the movie tries to decide what it’s name is. “King Lear: A Study.” “King Lear: A Clearing.” “King Lear: Fear and Loathing.” “A Film Shot in the Back.” The titles continue to pop up through out the movie, prematurely announcing THE END more than once.

Our main character turns out not to be Don Learo — although he does show up, played by Burgess Meredith, uncredited — but William Shakespare Junior the Fifth (Peter Sellars, uncredited, who would later clean up as a director of opera).

The situation in the world is dire, Shakespeare Jr. V explains in voice-over: “And suddenly it was the time of Chernobyl, and everything disappeared. Everything. And then after a while, everything came back. Electricity, houses, cars. Everything except culture — and meat. My task: to recapture what was lost. Starting with the works of my famous ancestor.”

Later we see him going through a forest with a butterfly net; he exultantly spots a reel of film in a pond. Cultural rescue to the rescue! By scribbling down bits of overheard conversation between Learo and his daughter Cordelia (Molly Ringwald!) he intends to recreate the text, or at least some text.

At this point it should be pretty clear that continuing with a plot summary is not that useful of an exercise. The movie is as fragmented as the scraps of Lear that waft through, sometimes by disembodied voices on the soundtrack, interrupted by the screeching of sea gulls.

This disjointed fragments-I-have-shored quality also gives it the freedom to swing wildly between two different modes.

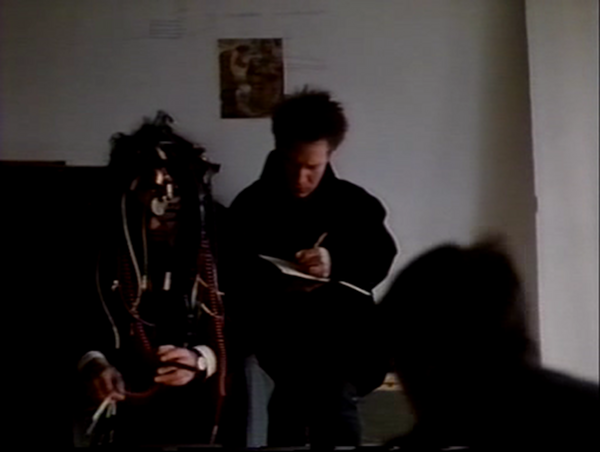

On one hand, there is ponderous lecturing on the meaning of cinema, given mostly by Professor Pluggy, from whom Shakespeare Jr. V seeks advice. He comes by his name honestly enough: he’s wearing spiralling patch cords as dreadlocks. It’s also, not coincidentally, Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps he is reciting some classic work of film interpretation, but it drags on tediously, as if he’s intending to bore his audience intentionally.

The other mode is a kind of improvisatory, vaudevillian jokiness. Here is Don Learo, over dinner, discussing Jewish gangsters Bugsy Seigel and Meyer Lansky: “Bugsy was a real killer. Not like this — uh, Richard Nixon.” In this vein, it’s not surprising that Woody Allen has a walk-on.

So how do you explain a movie like this? You have to use the Hebrew word freier — sucker. Golem and Globus, eager to do a prestige picture to mitigate their schlockmeisterhood, thought that underwriting a movie from Jean-Luc Godard was their fast lane to Cannes. They did not expect that they, themselves, would be the freiers.

The movie looks very much like a lark. Paid for by the Cannon Film Group.

______________

The Godard Roundtable index is here.