At first, I was nervous. I am not a hater by nature; I generally consider myself an enthusiast. How could I, then, participate in this Festival of Hate? Is there a way to responsibly choose something that’s worth hating on? Perhaps, I thought, I should just refuse to participate all together.

Noah asked me to pick my candidate for Worst Comic Of All Time. Being a good graduate student, I decided I needed some kind of rubric for determining Worst. Whatever I chose had to (A) Be made by competent, even skilled, creators (Ed Wood style badness wouldn’t do!), (B) Fail on its own terms to the extent they can be determined by a good-faith reading of the text, (C) Be not only bad but hateful in some way and (D) Influential.

There were several candidates that leapt to mind, but were unable to fulfill all four. The 300, for example, is hateful, made by a skilled creator and influential. But it doesn’t fail on its own terms. It is trying to be The Triumph of the Will of American Empire, a racist, pro-fascism pamphlet in which Western Society is attacked by ever darker, more exotic and queerer antagonists. On this front, it succeeds. It is, as a friend of mine put it, “a delicious pie baked by Goebbels.”

This search eventually lead me to Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V For Vendetta, a work that fulfills all four criteria with aplomb. It’s a competently made, terrible, hateful failure on its own terms that has, sadly, had some influence, particularly on the radical left, who really should know better by now. It manages to be brazenly misogynist, horrifically violent, and thuddingly dull all at the same time. It’s one of the few books that spawned a film adaptation that is both borderline-unwatchable and an improvement on its source[1]. Moore and Lloyd appear to have set out to make Nineteen Eighty-Four with a happy ending, and instead ended up making a leftish The Fountainhead.

For those not in the know, V For Vendetta is Alan Moore’s first longform work with original characters. An anarchist response to the election of Margaret Thatcher, V takes place in a fascist England after the whole rest of human civilization has been wiped out in WWIII[2]. Seemingly out of nowhere arrives V, a faceless terrorist who wears a Guy Fawkes mask and pursues two goals: revenge on the people who imprisoned and medically experimented on him in a concentration camp, and bringing down the government.

The book sets out to be a kind of action-thriller with political content, a work that uses a compelling story and the basic tools of mainstream comics (read: violence) to smuggle in a lot of pro-anarchism speeches and “thought provoking” sequences about individual and political freedom. On both of these fronts, it fails massively. It does not work as a thriller because we are never as readers in any doubt that V will succeed. He assures us again and again that he has a plan and at no point in the book does this plan seem in any kind of jeopardy[3]. He suffers no setbacks. He in no way struggles. Everything moves forward with the inexorability of a Greek Tragedy, but one that takes the gods’ point of view instead of the mortals. This sabotages any potential thrill the story might have as a story. Narrative tension generally relies on some mix between questions the audience needs answered and answers the audience has that the characters don’t. Neither is present in this book. The mystery as to V’s origin—really, the only even mildly compelling question in the text—is resolved before the first third is over.

The political content, such as it is, is no great shakes either. Yes, radical anarchy is preferable to jackbooted fascism. And in a world in which sanity means conformity to a genocidal, hyper-consumerist, corrupt authoritarian society, maybe we all need to go a little mad. V, however, ends just before fascist England actually falls. Moore gets to have it both ways, making a case that a radical anarchist state would be a really great thing without ever having to imagine for the reader what that world would look like. He even has V go to great lengths to explain that the riots, looting and murder taking place in England’s streets as the government collapses aren’t anarchy at all, but rather chaos. I suppose anarchy, like Communism, can never fail; it can only be failed.

The problem with shoddy political allegories like V For Vendetta (or The Dark Knight) is that the alternative realities they rely on to make their experiments work are so preposterous and rigged that they end up disproving themselves. True, were England to be taken over by Nazis, terrorism would likely be justified. But making a book arguing this case is a waste of time and energy. You might as well write a book making the in depth argument that if your Aunt had bollocks, she’d be your Uncle.

Well-crafted dystopian narratives understand this. Nineteen Eighty-Four doesn’t spend a lot of time arguing to the reader that the INGSOC should be overturned. Neither does Brazil contain a stemwinding speech about the tyranny of bureaucracy that Sam Lowry toils under. Instead, both bring to the table a rich examination of the psyche of those living under a dystopian state. Sam Lowry’s inner conflict between being a distracted dreamer and a bureaucratic climber slyly interacts with his gradual education into how his world and privilege work. Nineteen Eighty-Four’s portrayal of the gradual wearing down of Winston Smith’s psyche and of the way the totalitarian mindset is formed and reinforced at every turn, is harrowing and moving[4].

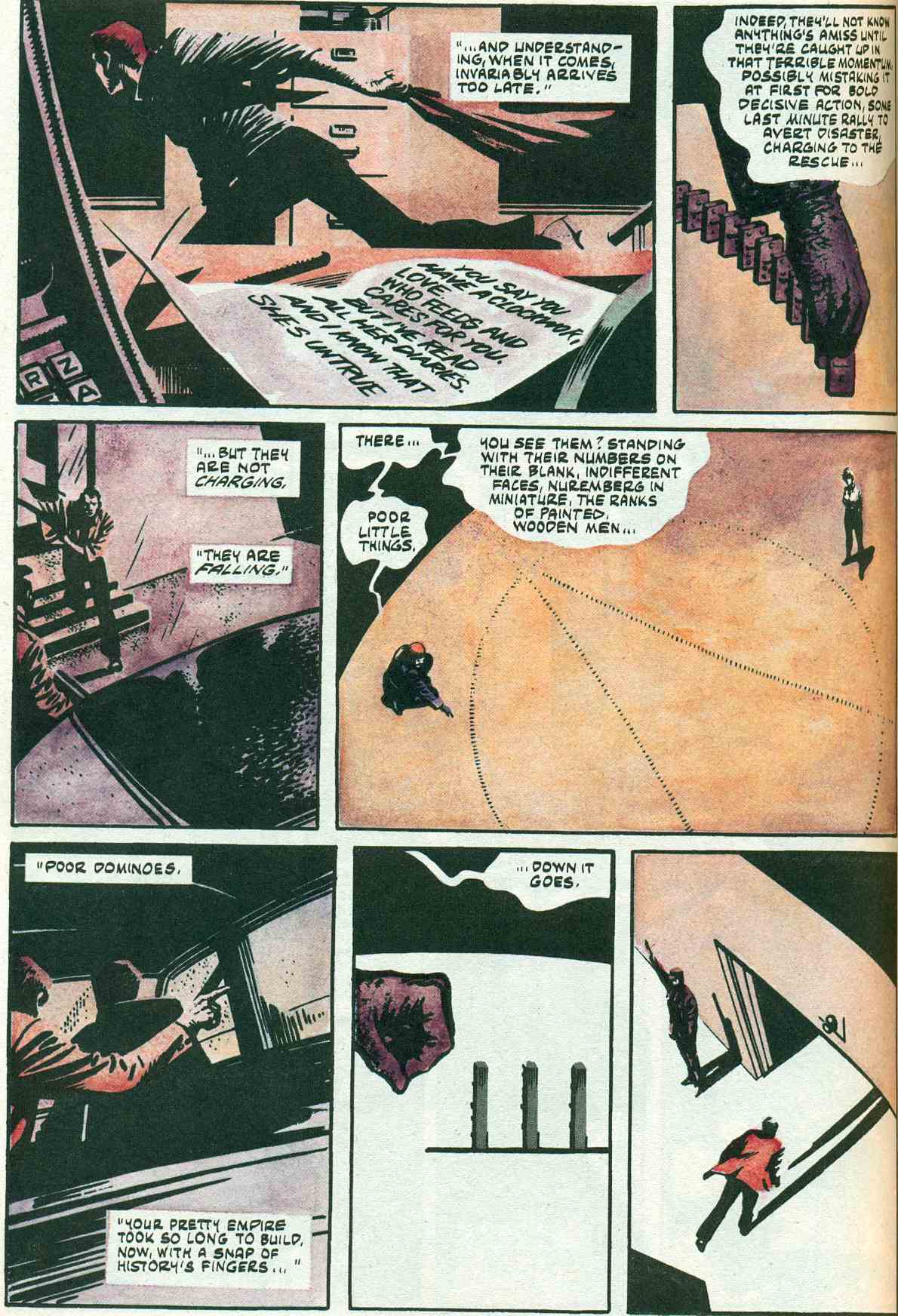

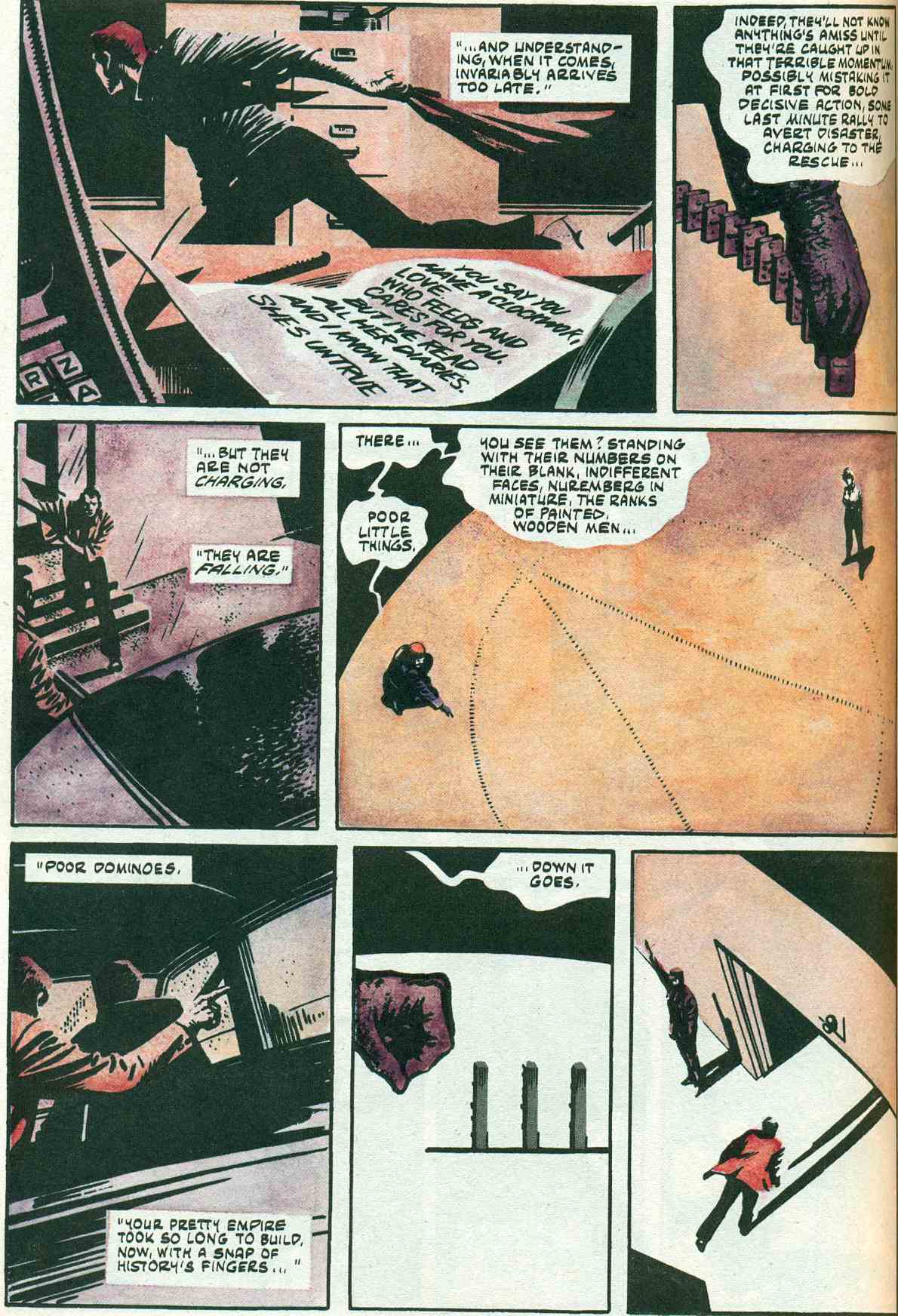

In order for V for Vendetta to pull something similar off, it would have to care about the characters who inhabit it. Sadly, the souls wandering its richly illustrated pages are mere pawns—or, to use the book’s own recurring image, dominoes—they are there to be set up and moved around as the narrative sees fit, toppled when expediency demands.

Nowhere is this more true than in the work’s treatment of Evey Hammond, V’s female sidekick[5] and eventual replacement. Evey is a shopworn narrative trope, the neophyte who joins the narrative so that the world can be explained to her, and via her, the audience[6]. Evey is the reader-surrogate within the novel, the person who has to try to make sense of V’s actions, while V is placed as the author’s surrogate, the explainer and shaper of the narrative. Repeatedly, we are reminded that V is creating something for us, something that seems chaotic, but that will reveal a pattern if we just wait and are patient. For example, this section comes from a journal of one of V’s “doctors” at the prison camp:

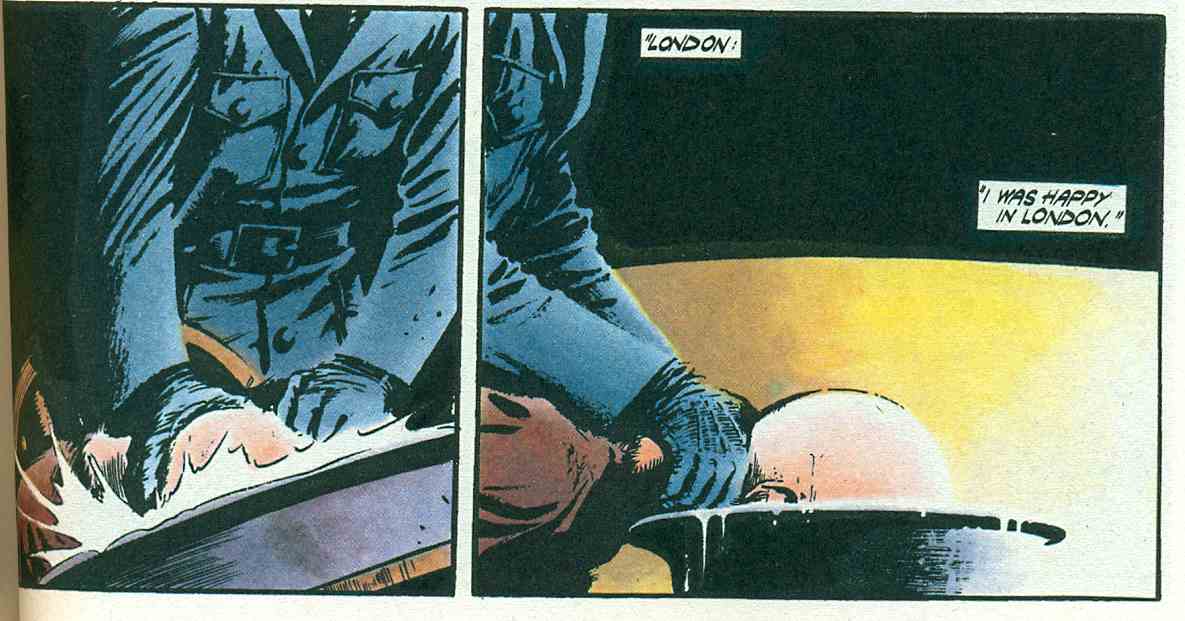

While later on, we see a recurring image of V setting up dominoes in his home base without being able to see the pattern, only to have it be revealed that it is his trademark V symbol right before he topples them all and the state of England:

If Evey is meant to be the reader and V is meant to be creator, it’s worth pointing out exactly how V For Vendetta’s creators feel about their audience. “I’m a baby,” Evey says to V. “I know I’m stupid.”:

V for Vendetta is the kind of book that proceeds from the assumption that the reader is a moron, and if only we were properly enlightened, we would agree with its creator. We are the gutless conformists, who just need a good stern talking to (and a little bit of torturing) to convince us of our errors. And here comes a guy who talks a lot like Alan Moore—all allusions and quotes from other sources, weird obscure jokes and puns, cryptic clues—to show us the way. It is, in that way, no different from The Newsroom: the work of a blowhard who is incapable of imagining anyone ever disagreeing with him, or a world in which he could possibly be wrong.

I suppose this shadow agenda of proving Alan Moore smarter than us would be all fine and good were the book to succeed in it. Sadly, amidst all that allusion and reference there’s a glaring neon sign that V for Vendetta is not nearly as smart as it thinks it is:

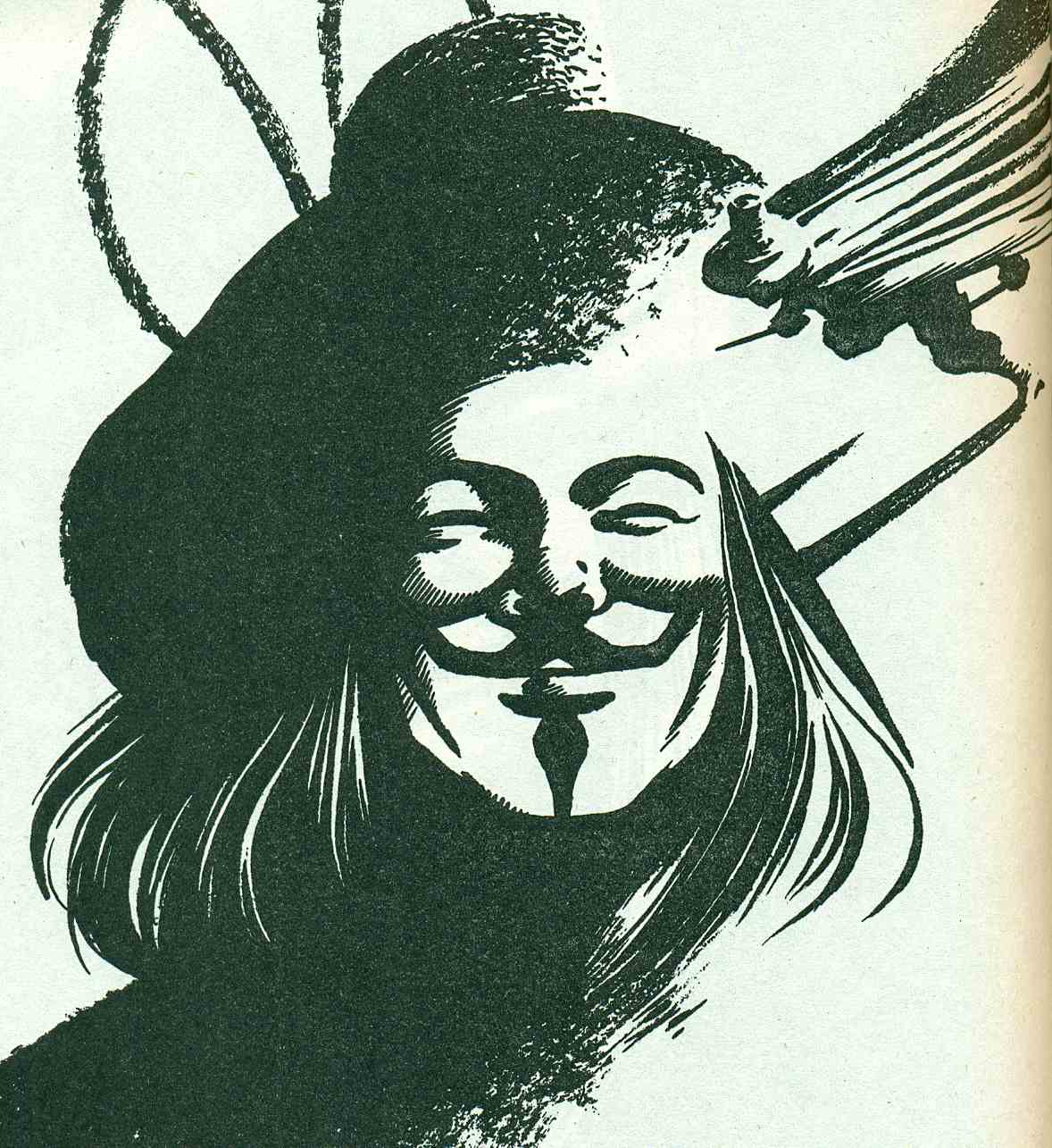

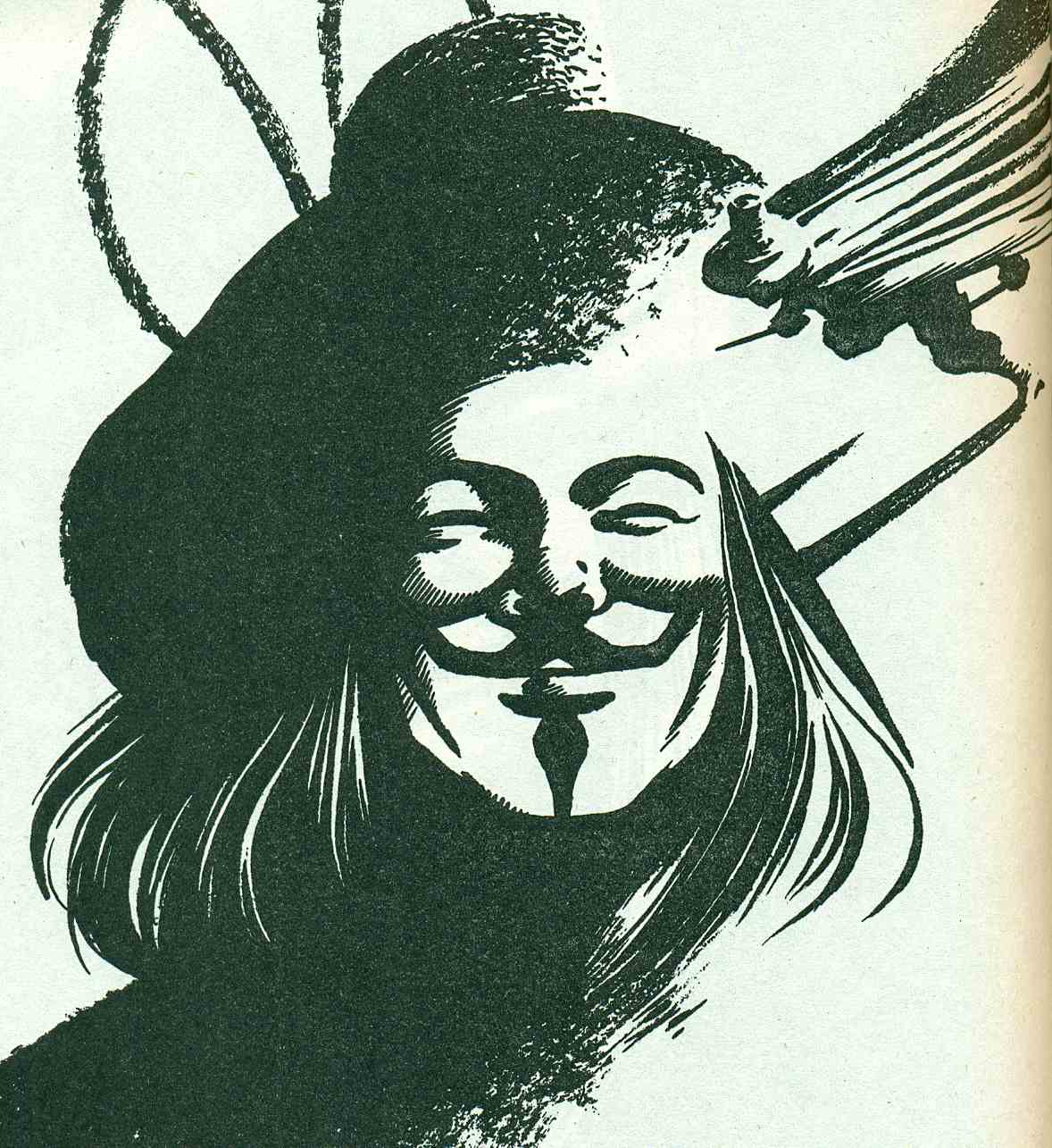

That’s our man V there. He’s wearing his trademark Guy Fawkes mask. Guy Fawkes is the book’s symbolic hero. Lloyd mentions in an afterward that he wanted to rehabilitate Fawkes because blowing up parliament was a great idea. But—and I hope this is obvious to many of you when you stop and think about it—it’s patently absurd to take Guy Fawkes as an anarchist-leftist superhero. Fawkes was a ex-soldier and Catholic extremist trying to overthrow an authoritarian anti-Catholic State and replace it with an authoritarian Catholic one. It’s just plain dumb to borrow the symbol of Fawkes without the slightest care for what it represents, just as it is an act of idiocy for the hacker group Anonymous and various members of Occupy—a movement I support, I hasten to add— to adopt the Fawkes mask as their icon.

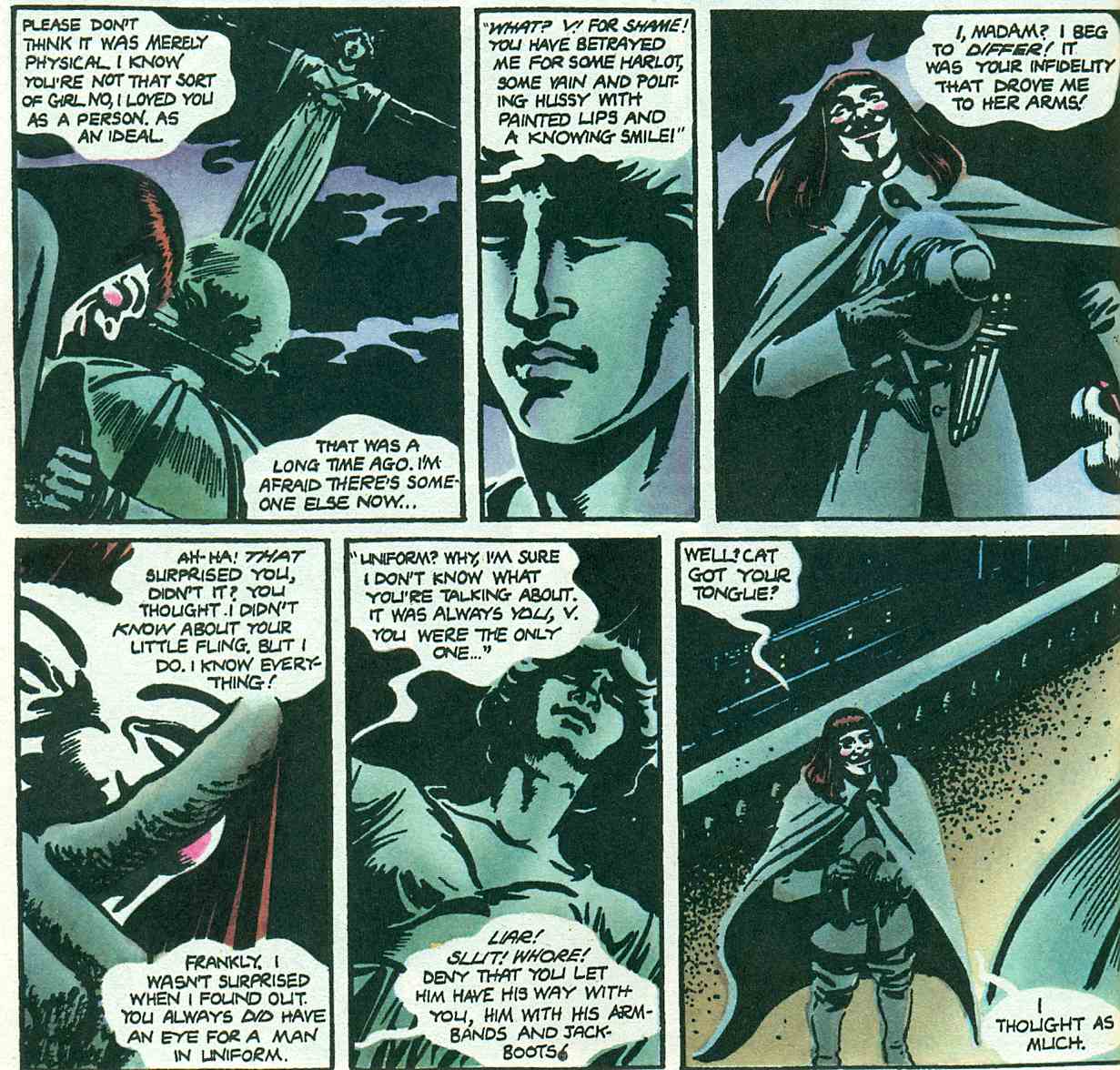

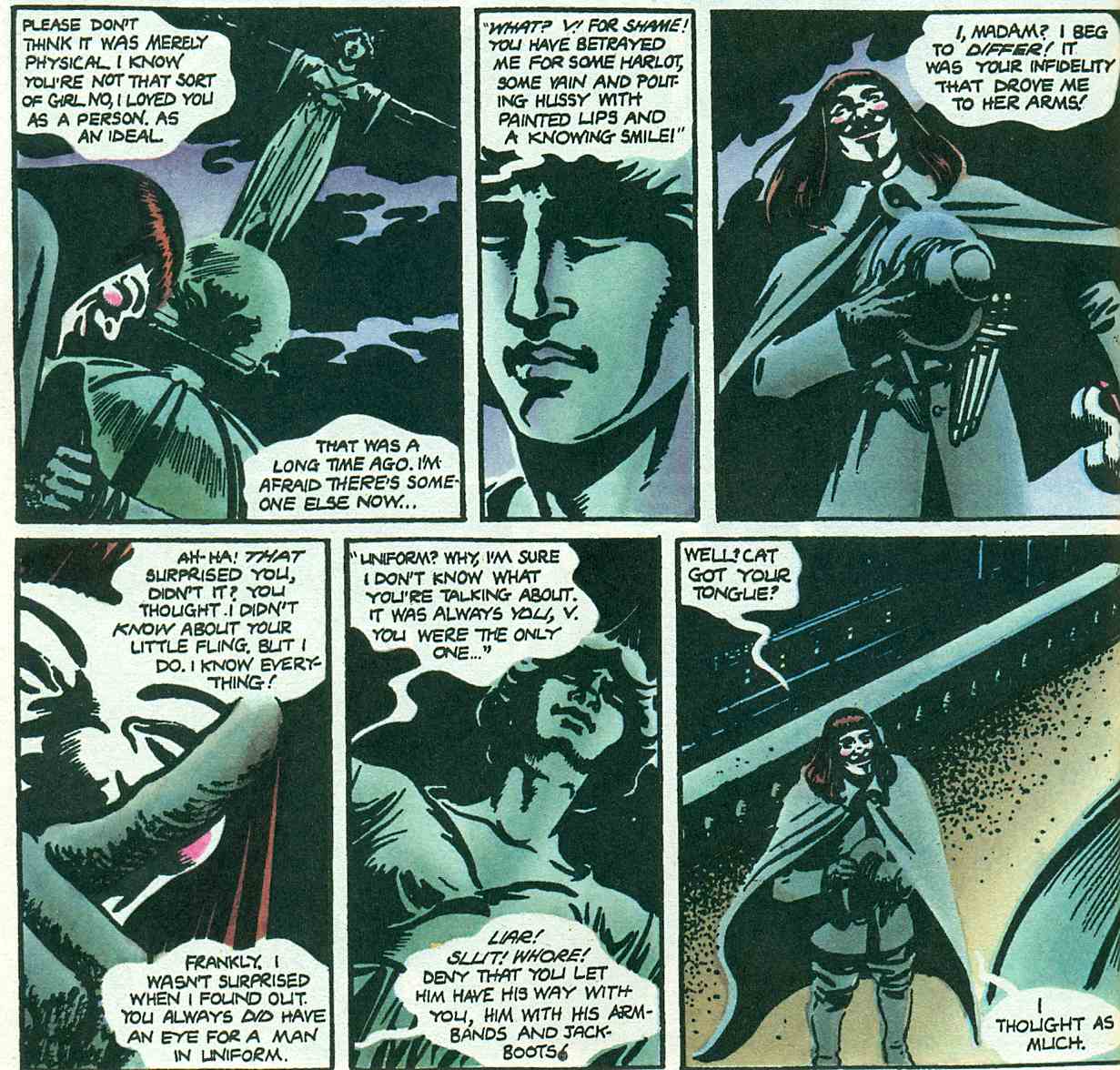

As the book wears on (and on, and on) it also gets derailed by its panic and anger at female infidelity, a crime that is punished with gleeful violence at every turn. On pages 39-41, V recasts his quest to free England as a lover’s spat with the female statue of Justice, who has cheated on him with Authority:

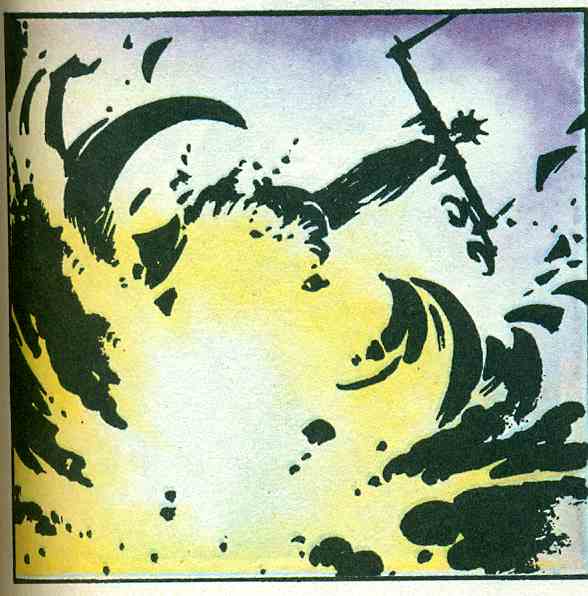

Care to guess how it ends?:

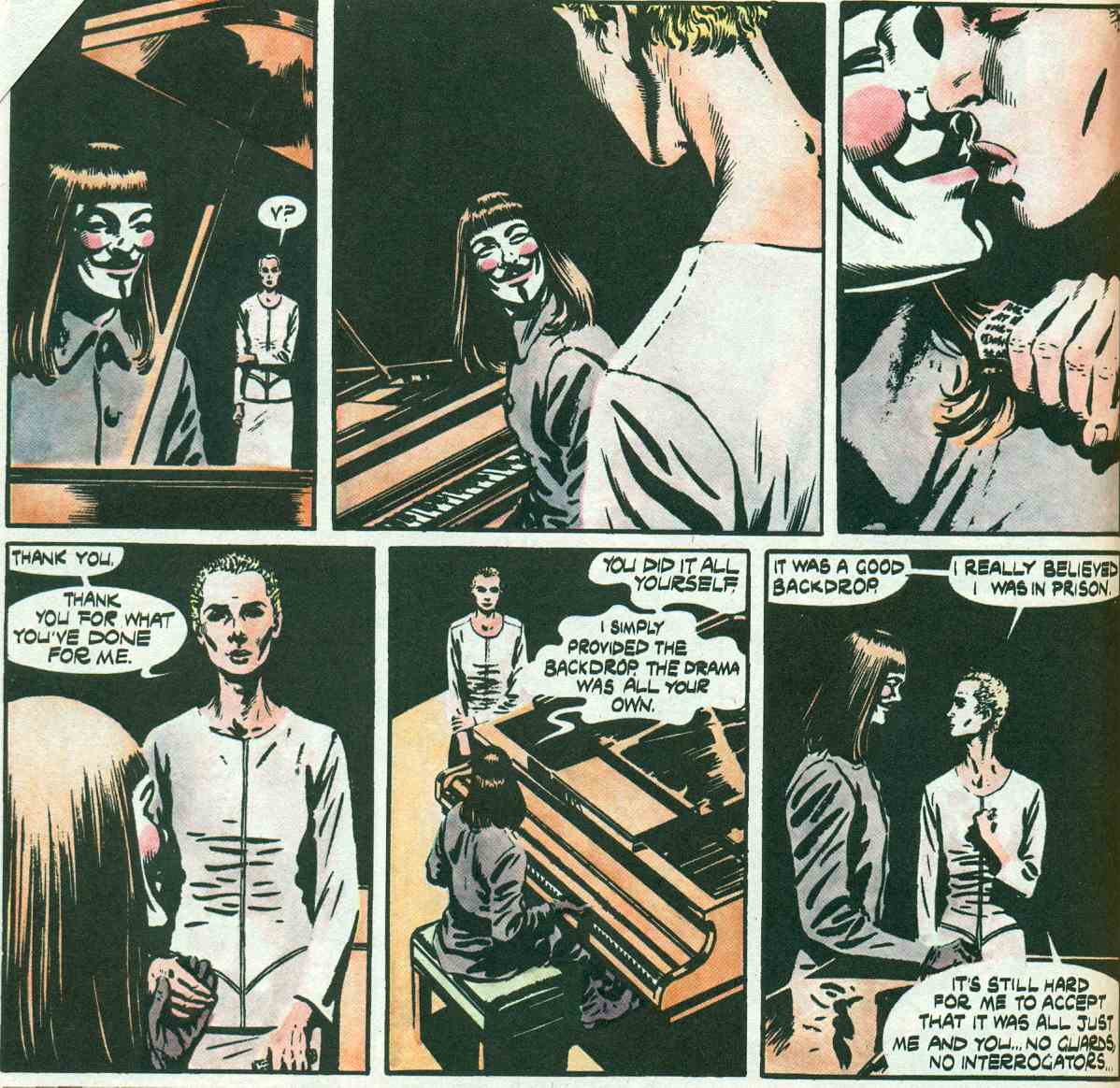

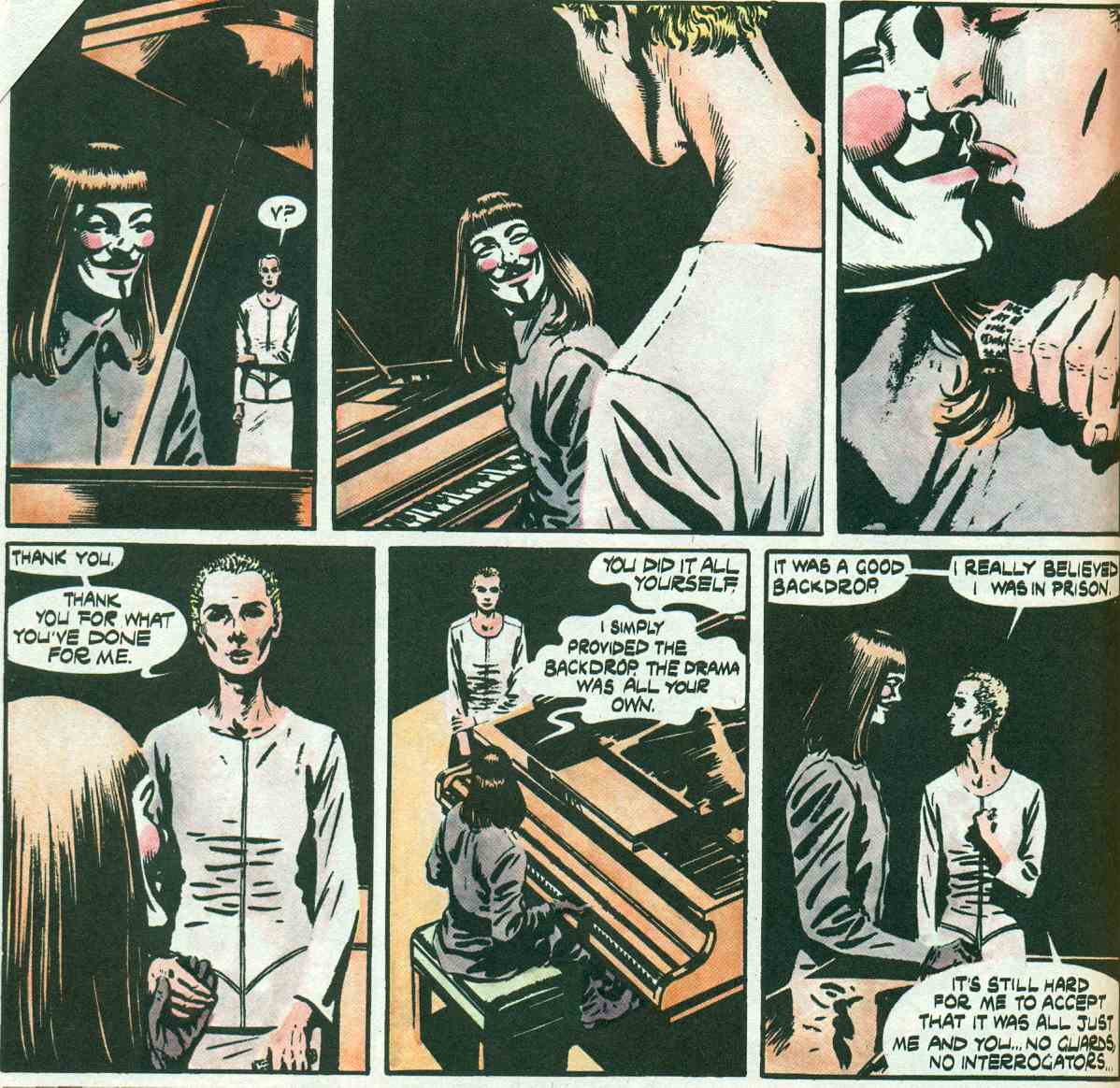

When Evey propositions V, he abandons her on the streets of England. Having nowhere else to go, she briefly takes up with a liquor smuggler named Gordon. With the inexorability of an early-eighties horror movie, as soon as she has sex with him, he gets killed by gangsters. After this, she is kidnapped, tortured, and interrogated, as faceless interlocutors demand to know the location of V and his plans. At night, she reads a letter from a fellow inmate which gives her the courage to accept death rather than betray V. It is then revealed that the whole kidnap/torture/interrogation thing was an elaborate ploy by V to set Evey free by helping her get down to the individual freedom that exists within us, the last thing that we control. While initially upset, here’s Evey’s eventual response from page 174:

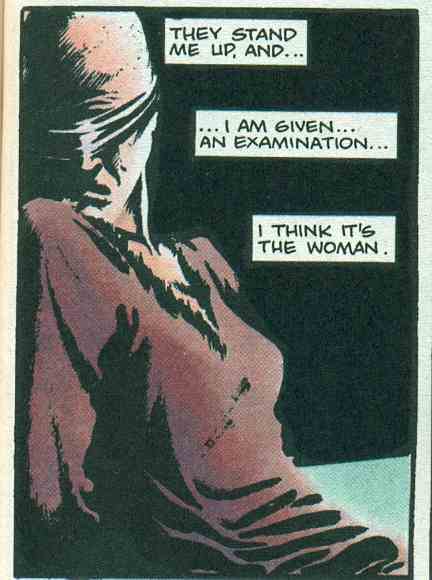

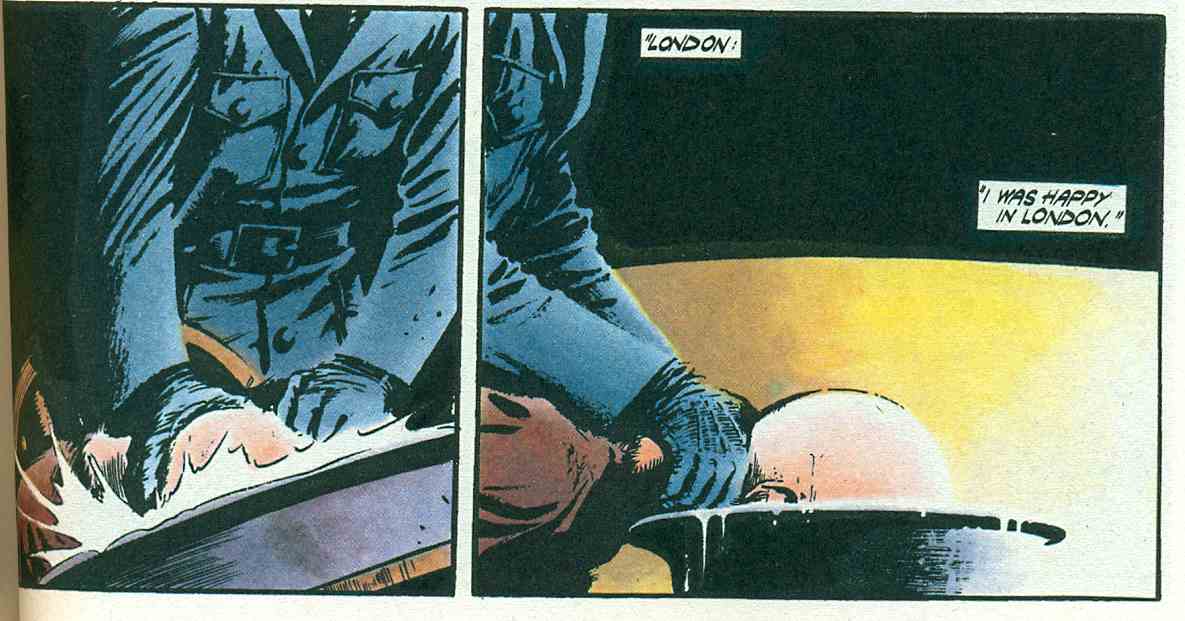

This would be hard enough to swallow were it not for the fact that Evey’s incarceration included sexualized imagery:

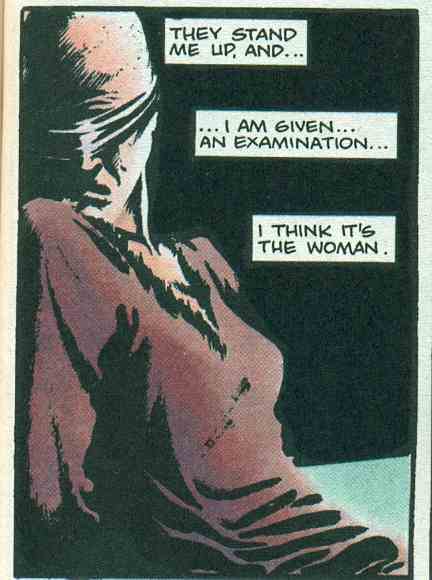

And actual sexual assault:

You see, dear reader, if you won’t see the light, we have the freedom, as filmmaker Michael Haneke put it, to rape you into enlightenment. Stockholm Syndrome is liberty. Also, War is Peace and Ignorance is Strength. Just shut your pretty little mouth and do what the author tells you. Never you mind that this is supposed to all be about radical individuality being the only way forward. You are radically free to agree and that’s about it.

Finally on the docket of cheating women who need to be punished, we have Helen Heyer. Helen becomes a regular presense in the third act of the book, as the (oddly fragile given that it’s supposed to be frighteningly all-powerful) society crumbles. The wife of a high-ranking fascist, Helen tries to maneuver her husband into the role of Leader by sexually manipulating his colleagues. She also refuses him sex. Helen is a classic misogynist caricature, simultaneously frigid and a whore, using her body to get ahead. It doesn’t work, of course. V sends her husband a videotape of her sleeping around, he murders her lover and is killed in the process. Helen’s plans come to naught and the book’s supposedly-cathartic orgy of chaos and violence ends on the final page with her about to be gang raped by hobos because she’s sick of trading sexual favors to them for food. Seriously. That’s the book’s ending.

All of Moore’s bad habits as a writer are on display in V, from its misogyny to the stentorian, hectoring tone of the text whenever its eponymous hero shows up to its frantic, desperate need to impress us with its creator’s brilliance. I feel I’ve only really scratched the surface of V For Vendetta’s terribleness here. Part of me was tempted to simply scan the song on pages 89-93 and write “Game, Set, Match,” underneath, or discuss the hackneyed and emotionally manipulative story about what happens to one of the prominent fascists’s wives after he dies, how she comes to miss his physical and emotional abuse when she has to take up a stripping job for money. Or catalogue the way in which each allusion—to everything from MacBeth to Sympathy for the Devil—is constructed not because of its actual relation to the material, but because it’s impressive.

Instead, let me close on a personal note. The reason why I find V For Vendetta so upsetting, the reason why it makes me so angry, is on some level political. I am a leftist. Unapologetically so. That V For Vendetta—with its nihilistic embrace of violence, it’s distrust of the institutions that will be required to enact any lefty agenda, its hatred of women and its love of coercion— has caught on amongst lefties, that in particular Guy Fawkes has been taken as a symbol of anything other than far-right religious terrorism is something I find particularly galling. I worry that at heart some of my fellow travelers on the Left feel reified by this work’s subtextual assertion that anyone who disagrees with them must be blinkered, an uninformed idiot who simply needs to be enlightened or blown up.

I suppose there is another way to read V, one where the surface and subtext are actually in constant conflict. One where the first chapter’s title (The Villain) is meant to be taken more seriously, where we are meant to see Evey’s torture not as she comes to eventually see it, but for the problematic and rapey coercion of one who disagrees with our main character. Maybe we are meant to see the downfall of the state as a complicated thing, and the gang-raping hobos not as a darkly ironic enforcement of Moore’s id but rather as a sign of complexity in the work. Perhaps V’s anarchist utopia is never shown because utopia means no-place and V is, in fact, wrong. Certainly there are panels and excerpts one could use to make this argument, but I am not the one to make it, nor would I really be convinced by that argument. It’s a bit too clever by half, a way of taking the book’s considerable weaknesses and claim them as strengths. Besides, Moore does a far better job in Watchmen of having the character whose worldview is closest to his also be a monster who does something unforgiveable for “the greater good.”

[1] This is almost entirely due to the presense of Stephen Fry

[2] Somehow this authoritarian hellscape on an isolated island nation with limited land and resources also manages to have a hyper-advanced sci-fi surveillance state and all of the middle class comforts of late twentieth century life, but there’s so many bigger problems with the text, we should probably let that one slide.

[3] V’s plan, by-the-by, is implausible within the world Alan Moore has constructed. We’re meant to believe that V, an escaped political prisoner, has somehow managed to amass a huge fortune, a wide network of real estate, hacked into Fate, the central computer that oversees all surveillance and activity within England and designed a meticulous plan to bring down the Government in under 5 years.

[4] Both also try to create analogues for our own time within their world, things that feel both exaggerated and frighteningly real at the same time. Brazil begins with a typographical error leading the State to torture and murder the wrong man, which feels ridiculous until you recall Maher Arar. Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Two Minutes Hate isn’t exactly Talk Radio, but it’s not not Talk Radio.

[5] You could argue that Evey is the protagonist of V and V the mentor figure. I actually think the book is confused about who its main character is. V doesn’t change, so he makes a shitty protagonist. Evey changes but is so thinly rendered and boring you can feel the book wanting to focus more often on V.

[6] Think Ellen Page in Inception.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.