Look and Learn magazine.

The home of cutaway technical drawings of everything from hydroelectric dams to airplanes; the repository of one page synopses of the venerable classics of literature, opera, and ballet; and the sanctum of illustrated lessons in history and geography. The Discovery Channel before people had even thought of the Discovery Channel. In its dying days, it hosted Tony Weare’s comic Rookwood of which I remember very little. In its prime, it serialized the single most popular feature in the entire magazine—The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire.

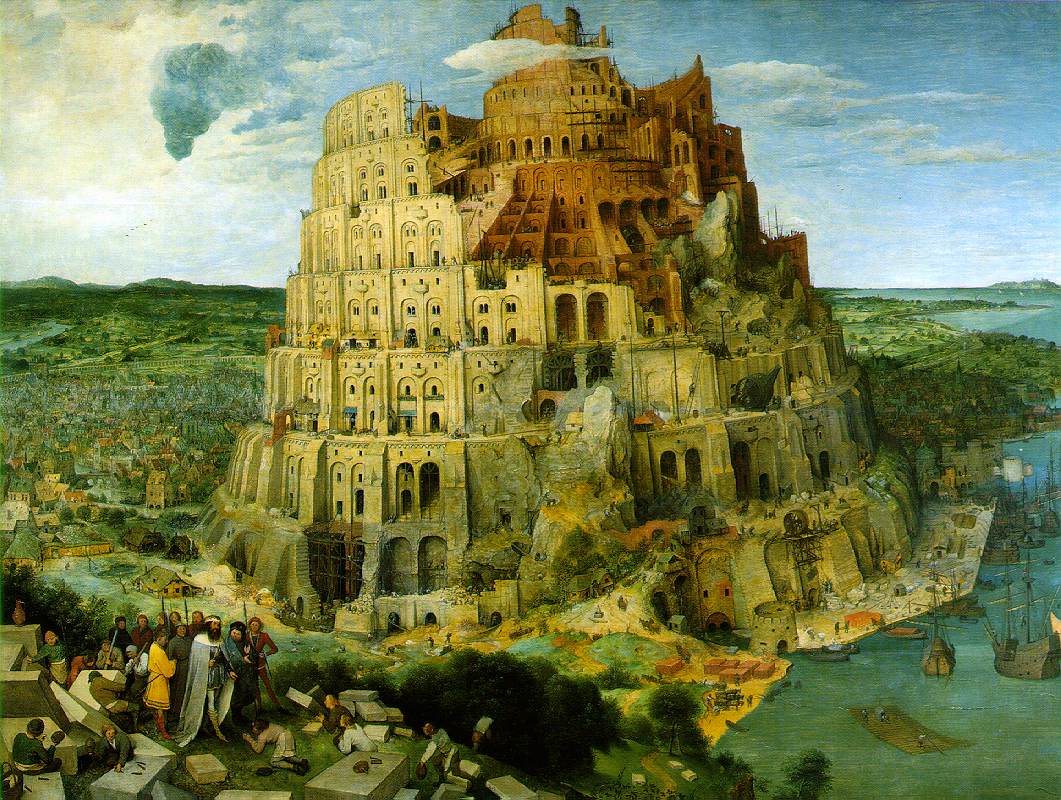

[The Tower of Babel, Pieter Breugel the Elder]

No one outside the British Commonwealth is likely to have heard of The Trigan Empire. The Wikipedia page for Don Lawrence, the strip’s most revered artist, suggests that he was an influence on the likes of Brian Bolland, Dave Gibbons, and Chris Weston. Neil Gaiman had this to say about the comic some ten years back:

“When I was a boy, Don painted a comic I loved. It was called The Trigan Empire — two comics pages a week, in the otherwise comicsless and dryasdust children’s magazine “Look And Learn”, which even schools who banned comics allowed. It was the story of something a lot like an SF Roman Empire on a distant planet, and was gorgeous.”

There were other comics in Look and Learn of course. I distinctly remember that the stories from various ballets (like Giselle and Petrushka) were presented in the form of comics for example. However, there is no doubting that Mike Butterworth and Don Lawrence’s The Trigan Empire was the king of the heap—the solitary reason why kids forced their parents to buy Look and Learn week in week out. There were other artists who followed in Lawrence’s wake once he broke with IPC (the magazine distributors) over pay but he was the good Trigan artist just as Barks was the good duck artist. For these children, The Trigan Empire became an education in what comic books could look like, never once realizing that Lawrence’s work on the series was in fact a high point in British comic art, one which has been rarely equaled.

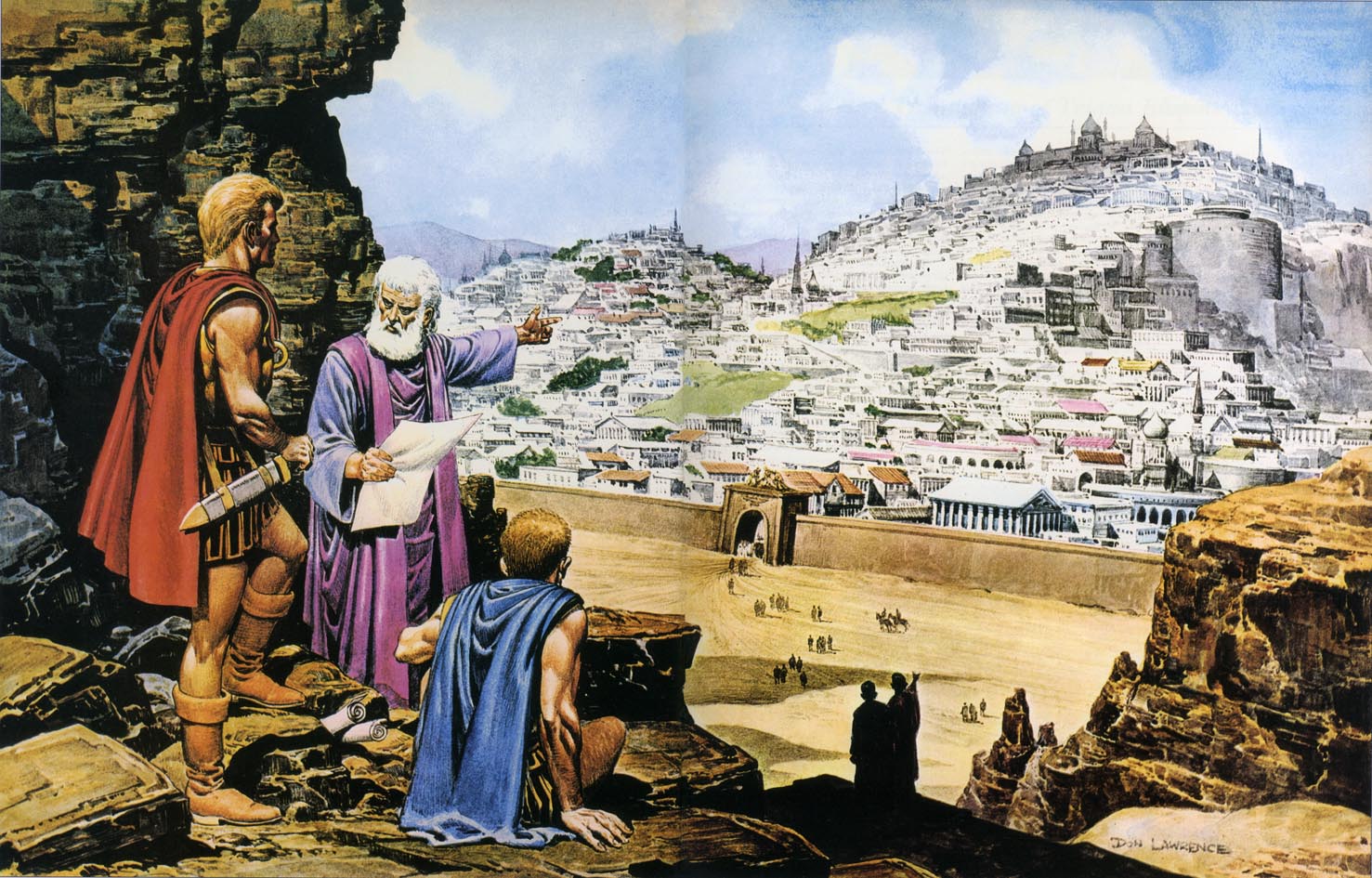

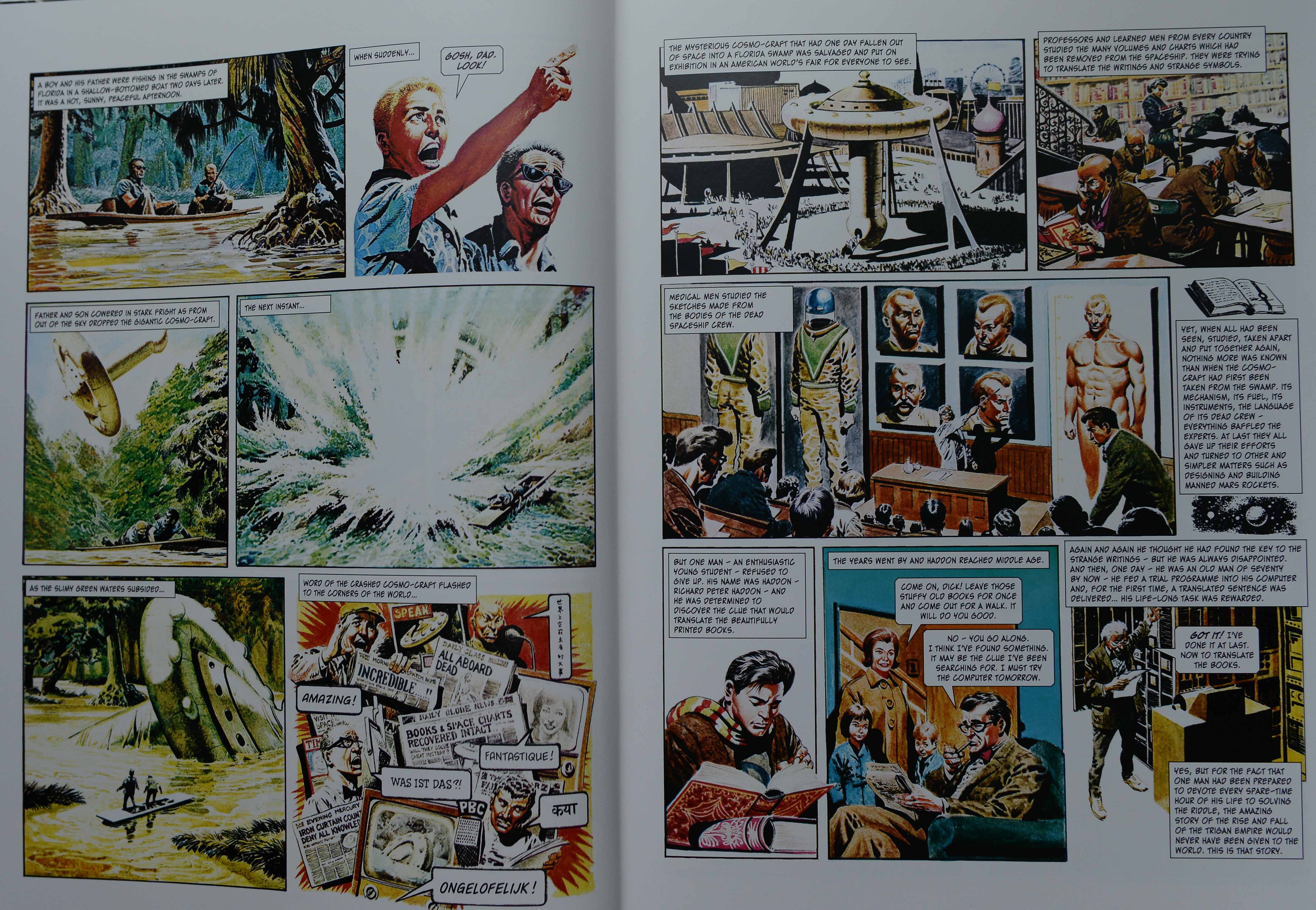

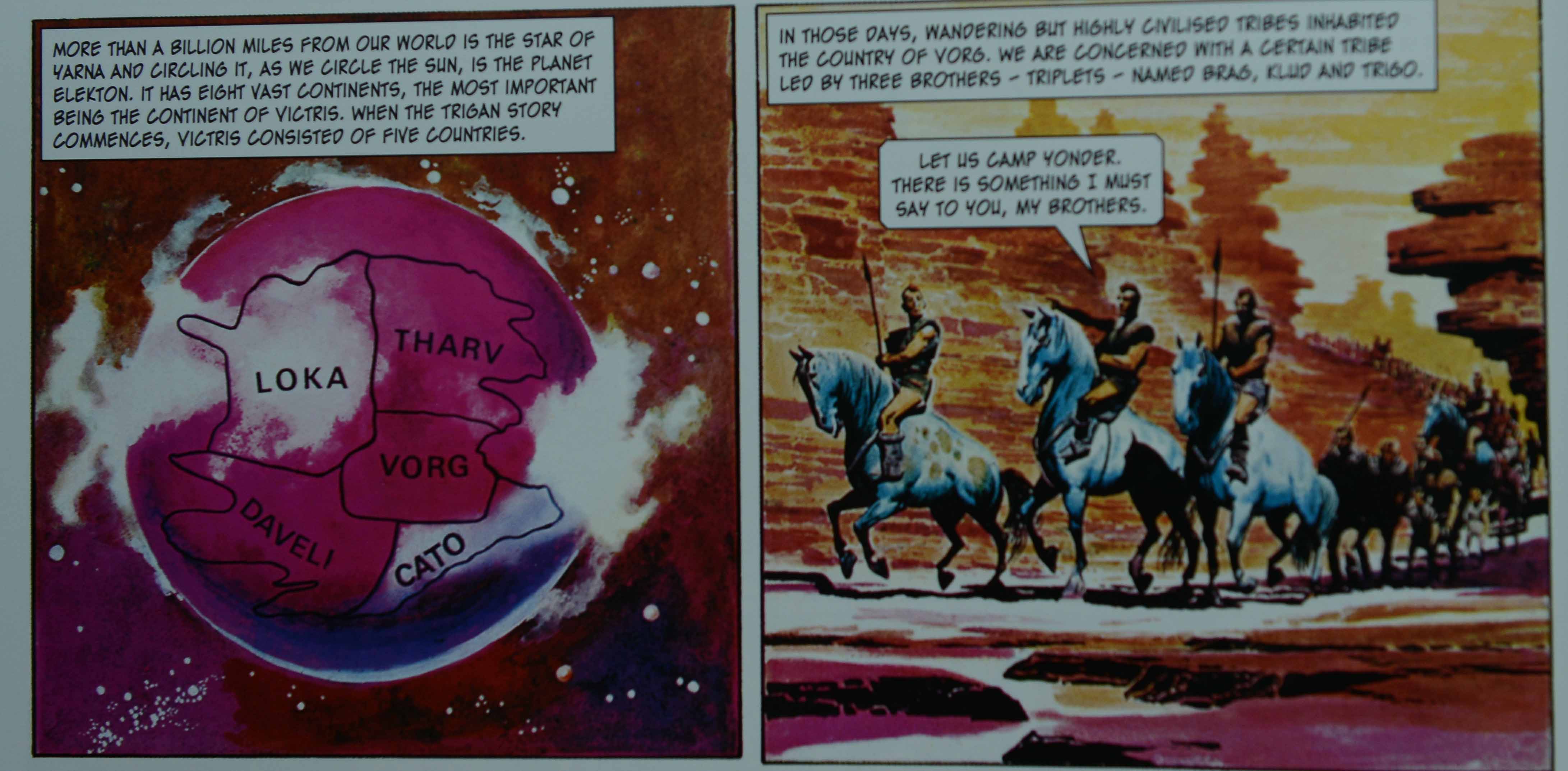

Here are the initial stirrings of The Trigan Empire as related on the second and third pages of its opening story (from the pages of Ranger magazine, its initial home).

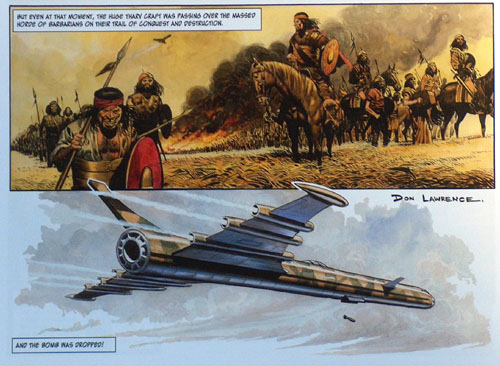

A cosmo-craft crash lands in Florida and the documents retrieved from it are translated after decades of research. From the documents a history of the world of Elekton emerges and the history of the rise and fall of the Trigan Empire. The Trigans are descended from the Vorgs, a nomadic race compelled to choose the ways of civilization due to the encroachment of their perennial enemies, the Lokans.

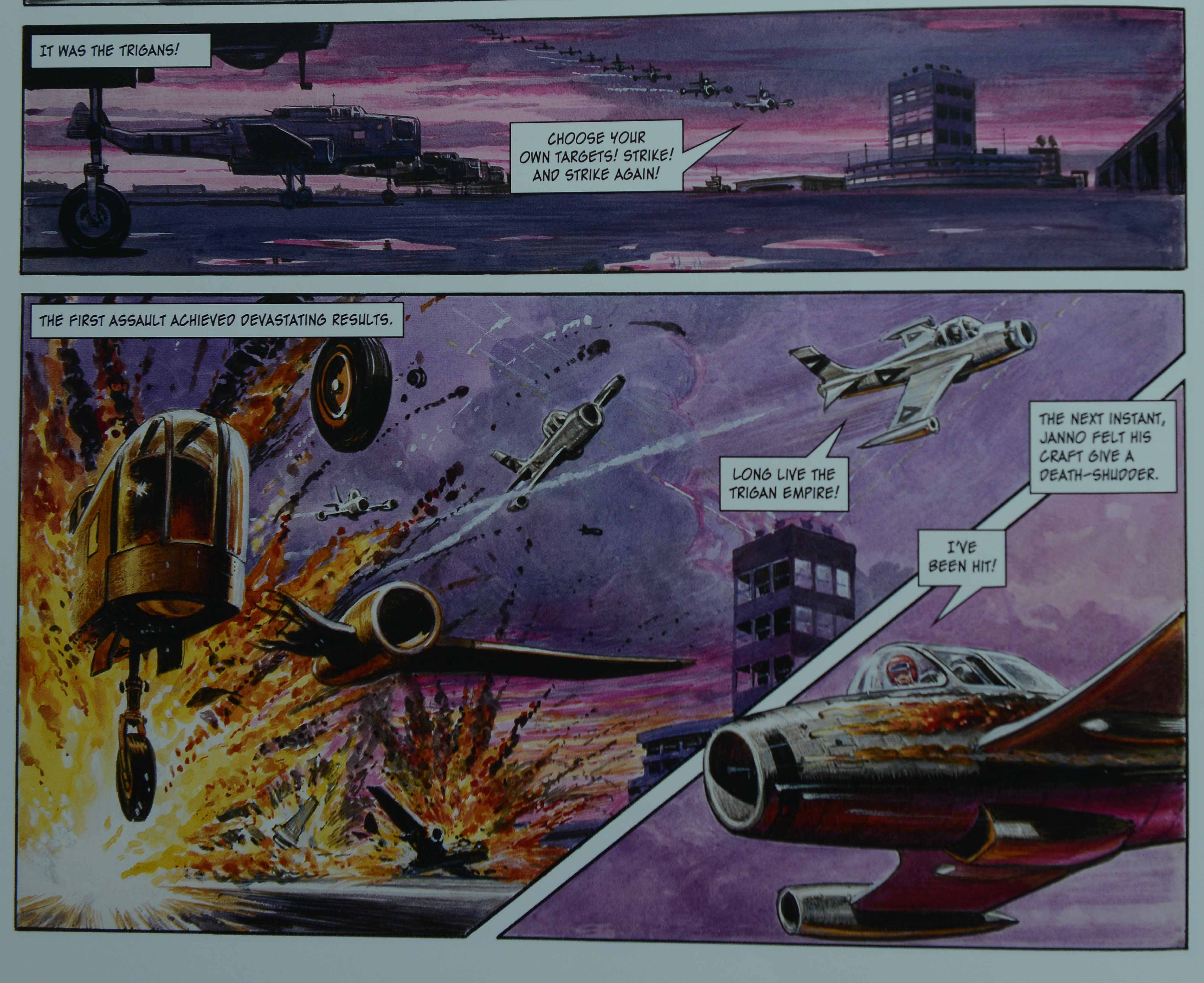

Elekton was a world of wayward scientific evolution where individuals wore the armor and togas of the Roman empire while piloting modern day battleships, fighter jets, and rockets. The aircraft themselves would vary from vague facsimiles of Harrier jump jets (the British fighter elite of the day) to World War 2 heavy bombers fitted with jet engines—all this with little concern for the aerodynamic stability of this confluence of design. In many ways, the serial became a perfect reflection of the contents of the educational pamphlet enclosing it. One imagines that this mishmash of historical themes was created at least in part to fulfill an educational mission, to stimulate the curiosity of young children in the direction of the progress of European man.

The entirety of Don Lawrence’s work on The Trigan Empire has been reprinted in 12 slim hardcover volumes by the Don Lawrence Collection (under licence from DC Comics), an organization situated in the Netherlands, this being the nation which has best preserved the artist’s memory and much of his original art. The comics read seamlessly in episodes of varying length, with the reprintings often starting on a single facing page thus obscuring the 2-page a week format of the original strip. New readers will be oblivious to the fact that every two page segment actually ends with a cliffhanger. As an “old” reader, I was periodically lulled into this smooth experience.

Take for example, the 18 page story titled, “The Man from the Future” (1975), a tale which represents Lawrence’s return to the strip after a year long break. It is also the first Trigan Empire story I remember reading.

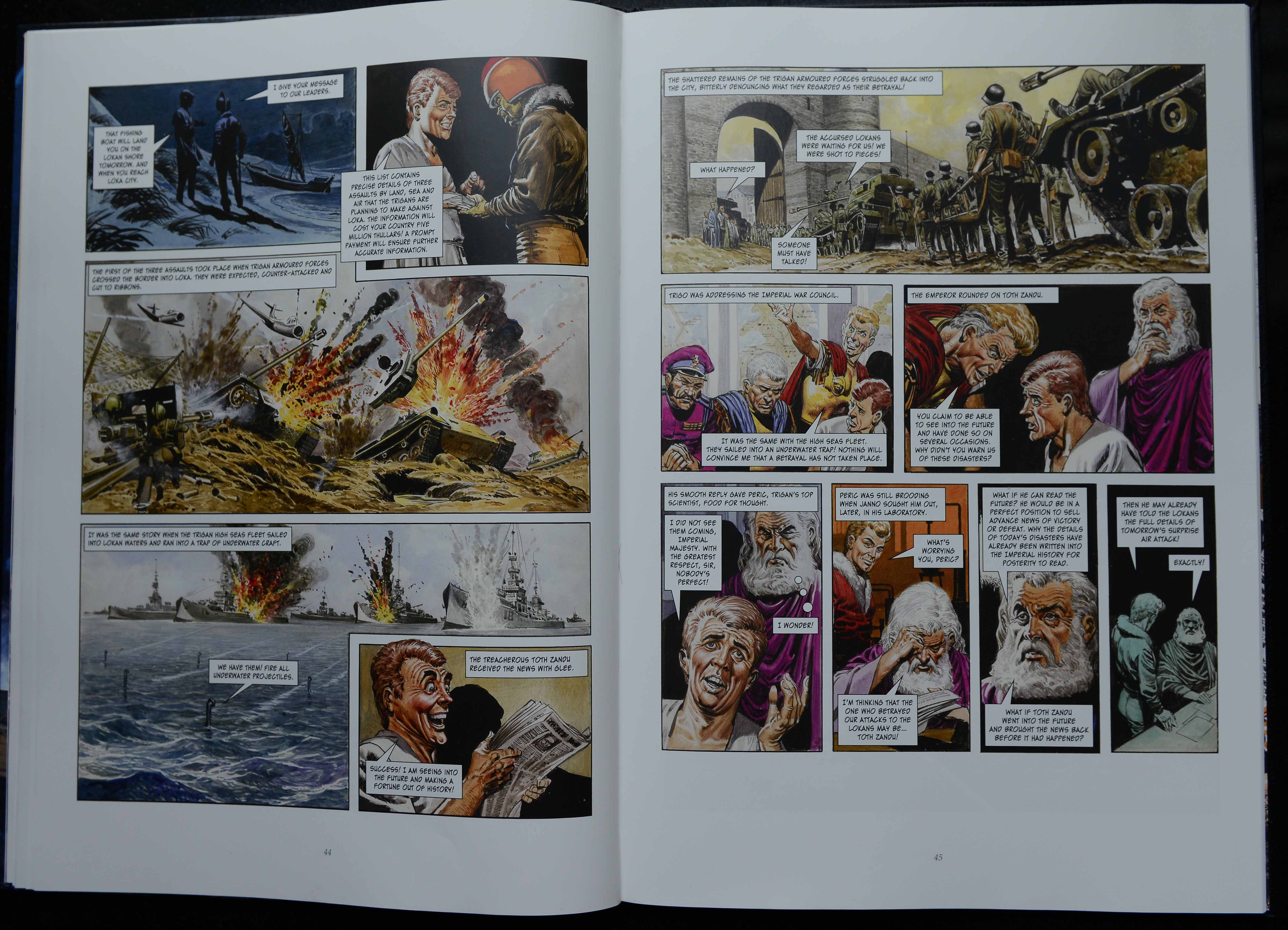

The story concerns a traveler from the future, an archivist who uses his intimate knowledge of the historical record for material gain and status. He arranges to buy a winning lottery ticket from its unsuspecting owner, “predicts” a Lokan attack thus inserting himself into the corridors of power, and then follows this up with a betrayal of the military plans of the Trigan political elite to the same Lokans. On every second page, the final panel shows (consecutively) the pride of the Trigan navy sinking, Toth Zandu’s profession to his young audience that he can look into the future, an attack on the Trigan Bay Bridge, two threats on Zandu’s life, the destruction of the Trigan fleet and so on – thus propelling the narrative onward with each passing week.

Zandu believes that he is invulnerable because the history books he has consulted have recorded his preservation to a ripe old age. The reader is constantly placed in a position of sympathy for Zandu as he escapes from each threat on his life before falling on the penultimate page in part due to his over confidence.

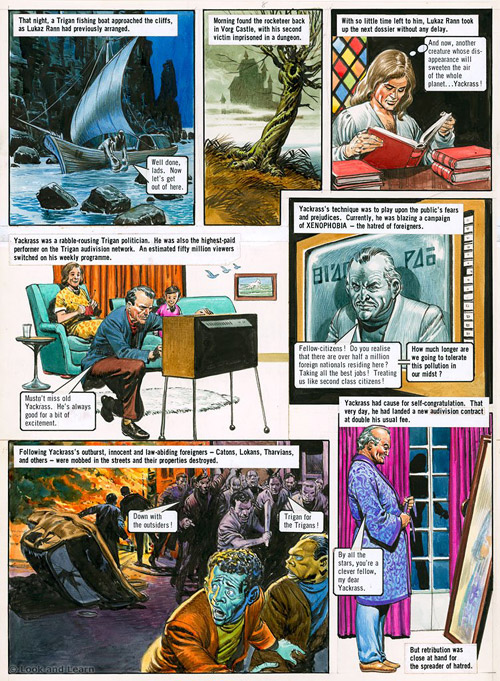

In a short but unrelated commentary, the editors for the Don Lawrence collection suggest that politics was rarely in the minds of The Trigan Empire‘s creators, the exception being the story titled, “The Mission of Lukaz Rann”, which takes in the subject of nuclear disarmament in the form of a planet killing bomb, and the practice of xenophobia in the guise of a demagogue based on the racist Member of Parliament, Enoch Powell.

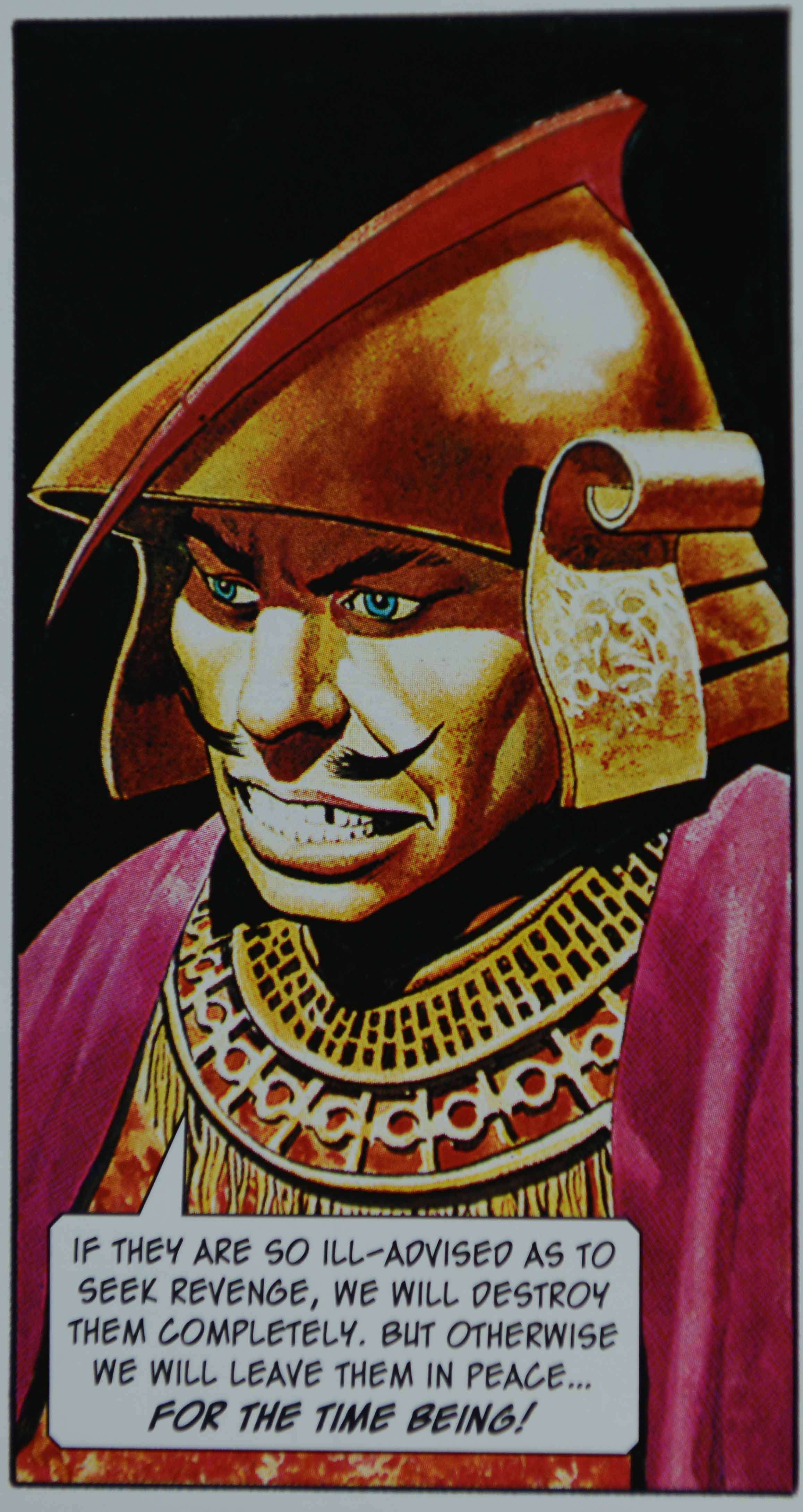

There is some modest political correctness in this most British (post imperial) and conservative of comics. The dastardly Lokans who are colored green actually conform to no obvious race in many instances. They sometimes look like bearded Caucasians with a greenish hue and at other times like Africans or Asians (Indians?). Their one distinguishing trait is a perpetual state of irritation and fury, all knit brows and snarling teeth. A far cry then from their initial appearance in the first Trigan Empire tale where they seemed like refugees from Ming the Merciless’ army albeit with samurai headdress.

As for the barbarians at the gate, they were inevitably the Mongol hordes and vicious Native American “savages.” Maybe there were some Parthians thrown in for good measure but I don’t remember any. Just as the technology of the Trigans represented a patchwork of Western civilization and military dominance—from swords and sandals right up to weapons of mass destruction—so too did their enemies reflect the unchanging status of Western vulnerability as described by Joseph Schumpeter in “The Sociology of Imperialisms”:

“There was no corner of the known world where some interest was not alleged to be in danger or under actual attack. If the interests were not Roman, they were those of Rome’s allies….Rome was always being attacked by evil-minded neighbors, always fighting for a breathing-space. The whole world was pervaded by a host of enemies, and it was manifestly Rome’s duty to guard against their indubitably aggressive designs.”

The entire premise of the stories in The Trigan Empire was that they were transcribed from historical documents retrieved from a spacecraft. This would suggest a hagiographic record and, as Butterworth, intimates in “The Man from the Future,” outright lies. The Trigan hegemony triumphantly bringing peace and good will to the surrounding provinces and also ushering foreign nationals to its shores—this triumph of Western civilization resembling a fairy tale vision of the beneficent Pax Romana transferred to a semi-futuristic “Europe” bordered by barbarians and villains.

Consider more carefully the two pages shown above. The Lokan artillery divisions with their modern helmets are laying waste to a field of Trigan tanks (which look curiously like mutant combinations of a German Tiger and Panther tank) in a bravura display of destruction by Lawrence. Time and again throughout his tenure on the series, Lawrence would display his mastery of smoke, fire, and the implements of war.The retreating armies of the Trigans are not in the familiar bowl-shaped caps of the British infantry, nor the ceremonial galeas often seen on the heads of Trigo (the emperor) and his retinue. Instead, we find the equally familiar round helmets of the German army (the Nazis were of course enamored of all things Roman).

Perhaps the Nazis simply had the most attractive uniforms and the best looking tanks. The British made toy tanks I was given as a child included not only a suitably patriotic Saladin but also a German Tiger tank and a Jagdpanther. When you’re producing two water-colored pages (or more) every week for a children’s magazine, you can probably be forgiven for reaching for the coolest military ephemera at hand, particularly those which would be most attractive and recognizable to a young audience.

Yet it is hard to resist the suggestion here of an alternate history where the “civilizing” force of the Nazis has encompassed an entire continent producing a land of general tolerance, as well as law and order. A careful discussion of politics was beyond the remit of the series but the script clearly shows a subtle understanding of history out of keeping with its primary purpose as entertainment for under 10 year olds. A history where Churchill is both celebrated as a national hero and reviled as a man of unholy inclinations as demonstrated by his following statements:

“I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum. It is not necessary to use only the most deadly gasses: gasses can be used which cause great inconvenience and would spread a lively terror and yet would leave no serious permanent effects on most of those affected.” (12 May 1919)

“I want you to think very seriously over this question of poison gas… It is absurd to consider morality on this topic when everybody used it in the last war without a word of complaint from the moralists or the Church. On the other hand, in the last war bombing of open cities was regarded as forbidden. Now everybody does it as a matter of course. It is simply a question of fashion changing as she does between long and short skirts for women.” (6th July 1944)

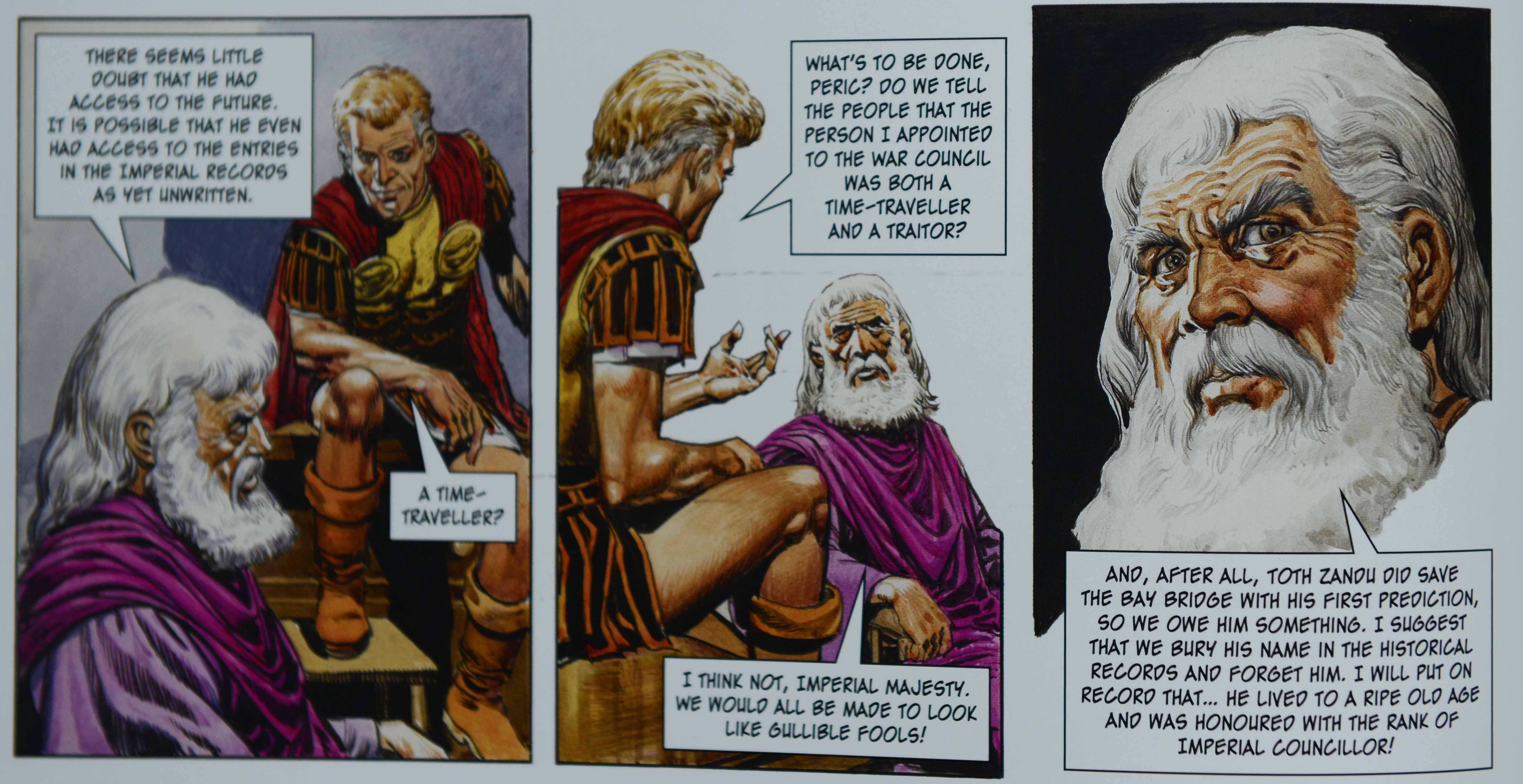

When Toth Zandu’s deceit is finally discovered, Peric— the wisest man on Elekton, and clearly modeled on a stateless Greek—decides that history must be altered. But not only in order to deceive Zandu but to cover up their own foolishness:

In this sense, “The Man from the Future” affirms that history is not only written by the victors but also to preserve the dignity of the ruling class. If there was any semblance of tyranny or embarrassment in the record of the Trigan Empire, it has been systematically but ineffectively wiped out. For there is another unspoken question at the end of this tale. As I have mentioned, the comics which comprise The Trigan Empire are supposed to be histories in themselves. Who then wrote this “correct” history of Elekton and uncovered Peric’s deception?

Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle concerns just such a history where the Axis have triumphed and the “yanks” are now the “white barbarian Neanderthals.” Yet the reality of this physical apprehension is questioned by the book within a book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. The fake “antiques” peddled by another character, Frank Frink, are authenticated by mere pieces of paper as Wyndam-Matson (Frink’s employer) relates to an audience of one:

” ‘..a gun goes through a famous battle…and it’s the same as if it hadn’t, unless you know. It’s in here.’ He tapped his head. ‘In the mind, not the gun.’..[ ]…’I’d have to prove it to you with some sort of document. A paper of authenticity. And so it’s all a fake, a mass delusion. The paper proves its worth, not the object itself!'”

In melding the objects of war and civilization almost indiscriminately and in professing the wavering basis of the historical record, “The Man from the Future” partakes (if on a more elementary level) of this turmoil in historicity. For it calls into the question the entire beneficent record of the Trigans.

Like a scribe taking in the history of European man a millennium hence, it provides a panorama of Western civilization—the histories contiguous and undifferentiated by mere national boundaries. It relates a heroic and selective history of the Greeks and Romans but also communicates more subtly the devices of Fascism (and Hitler in particular); indulging simultaneously in the belief that all men are created equal while holding to disfiguring conceptions of everything without the borders of the empire—a surreptitious and perhaps unwitting interrogation of the basis of Western civilization from the perspective of a Boy’s Own adventure comic.