Last week I wrote about the first four stories in Moto Hagio’s “Drunken Dream.” All of those stories had coherent themes, recognizable characters, and linear plots with a beginning, middle, and end. They all also, and not coincidentally, sucked.

The title story of the volume, “A Drunken Dream,” is, on the other hand, an incoherent mess.

And thank goodness for that. As I said in the last review, Hagio is really poorly suited to telling stories that make sense. There are shojo titles I love that are predicated on strong character development, subtly observed relationships, and psychological acuity. But that is not at all where Hagio is coming from. At least in the work of hers I’ve read, her characters are conglomerations of stapled together clichés; her relationships are little more than heartfelt declarations and melodramatic gush; her psychology is (at least on the diagetic level) pop piffle and the occasional yawning absence. You get more realistic motivations and more subtle characterization in your average super-hero title — and that, true believers, is a fucking low bar.

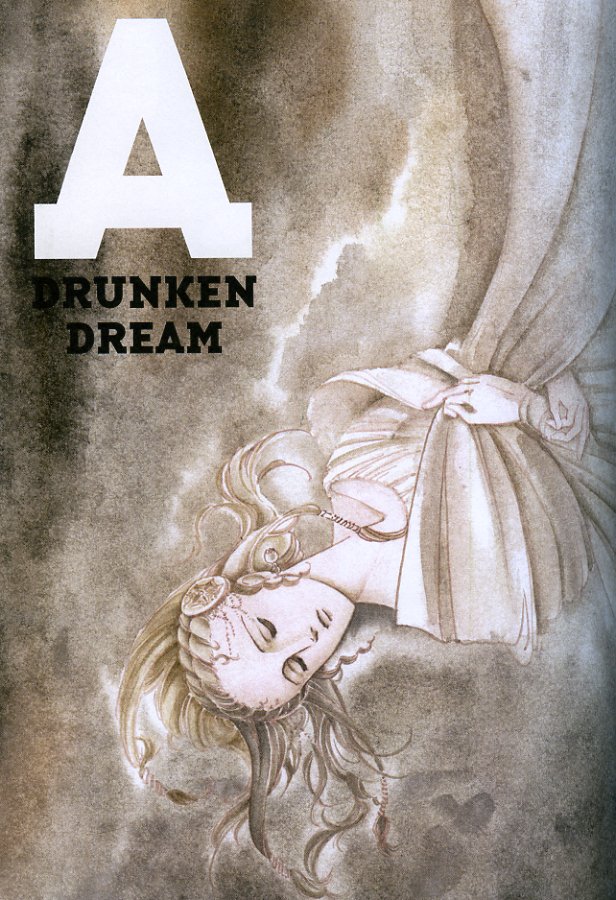

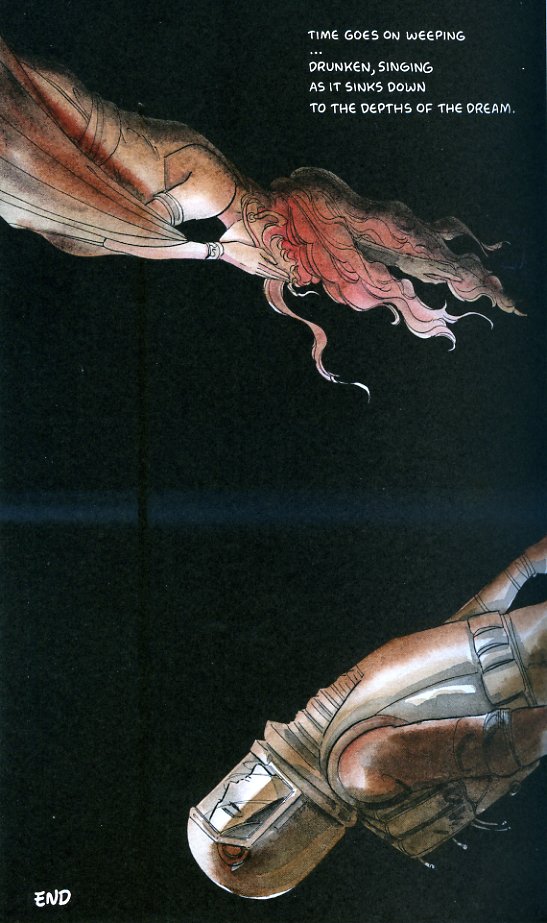

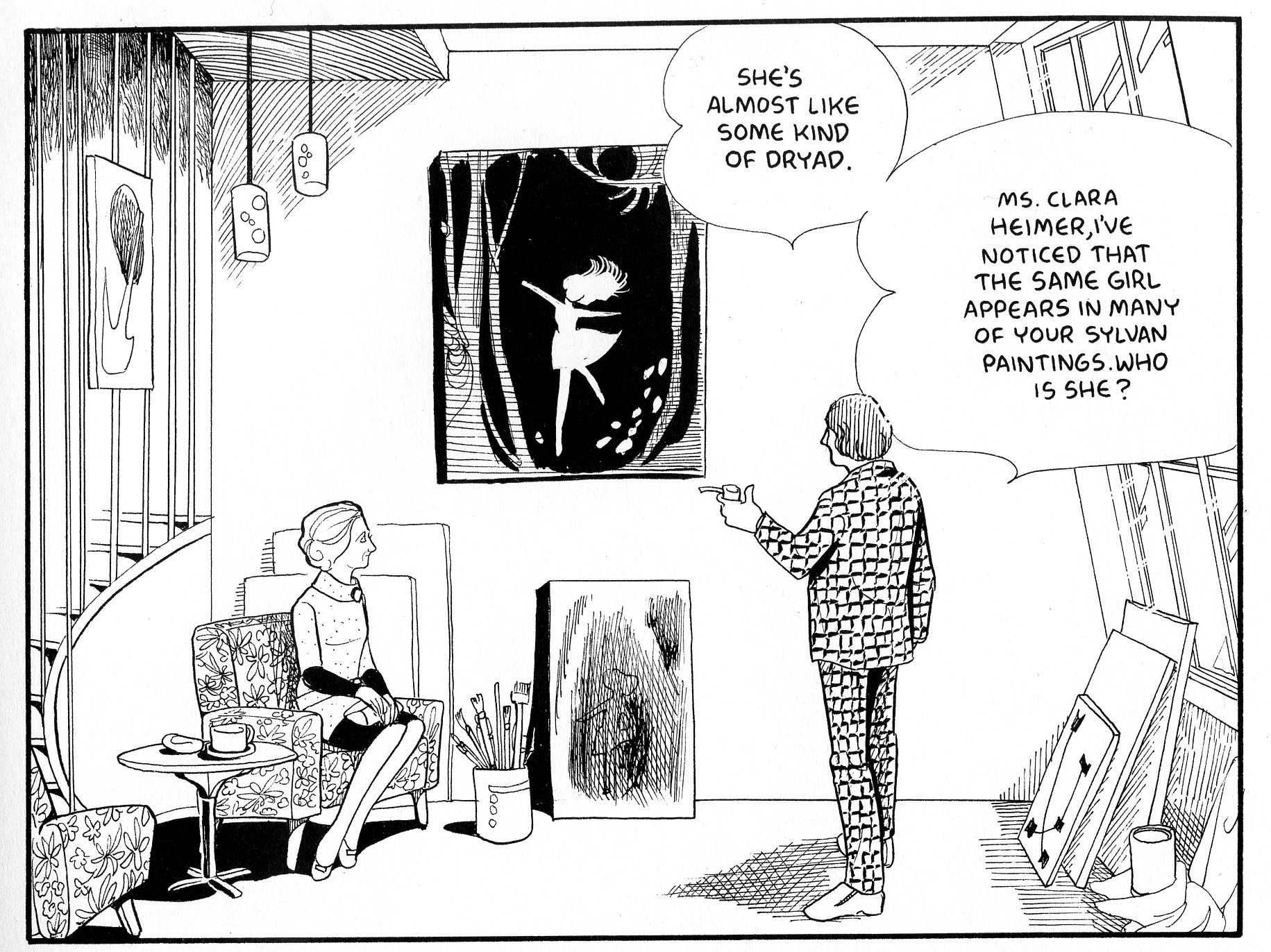

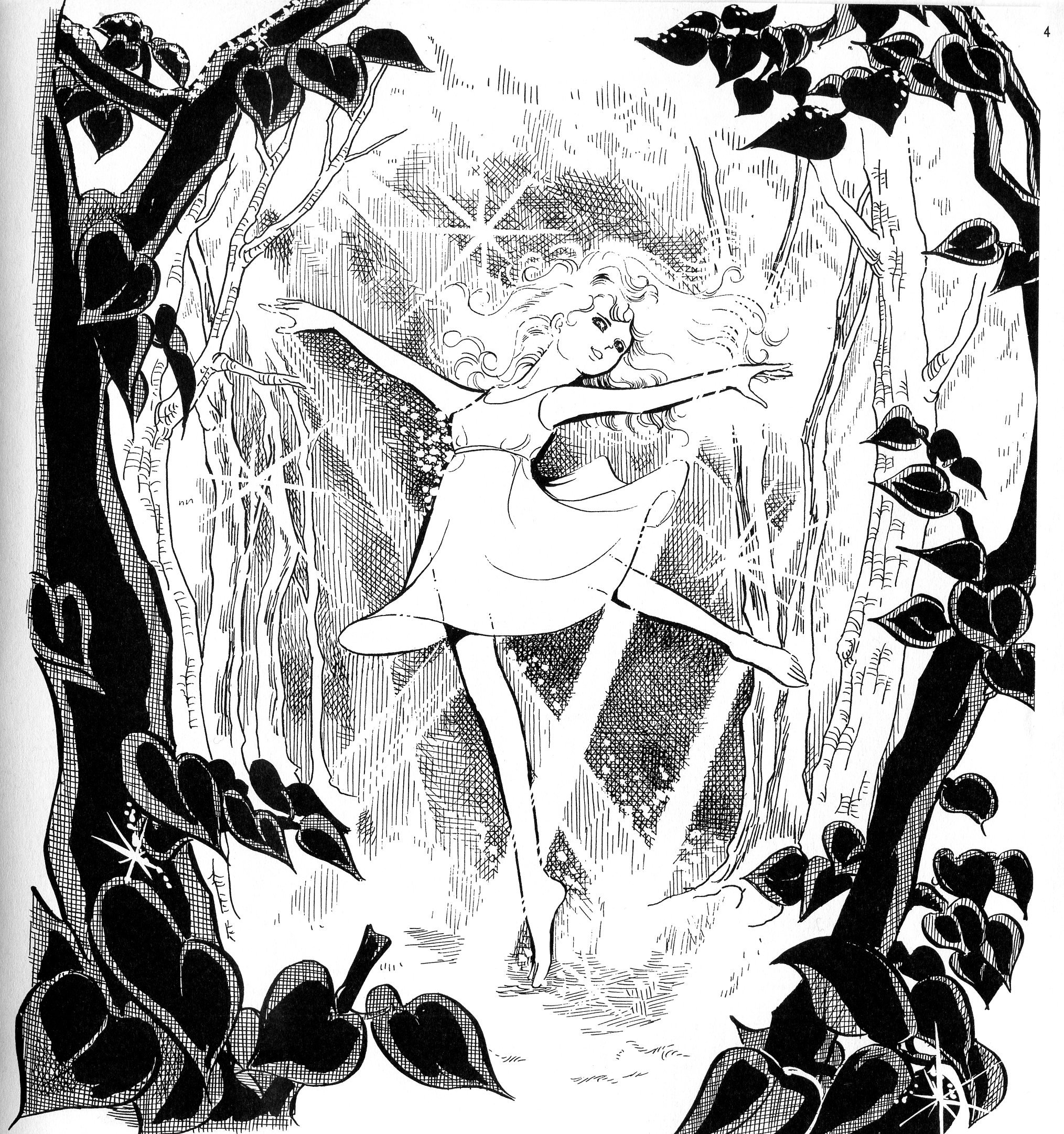

Which is why the best Hagio that I’ve seen is the Hagio that doesn’t even gesture in the direction of realism —unless you count thumbing your nose as a gesture. The story “A Drunken Dream” is a fine example. In fact, the narrative is a tour de force of non-specificity. The splash page shows a woman in some sort of traditional period dress upside down drifting through brownish-red n-space.

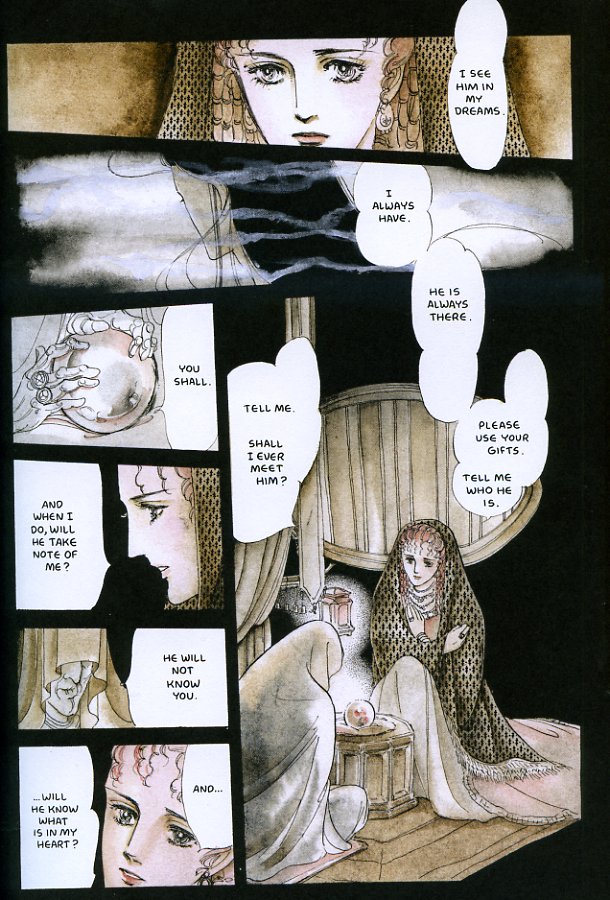

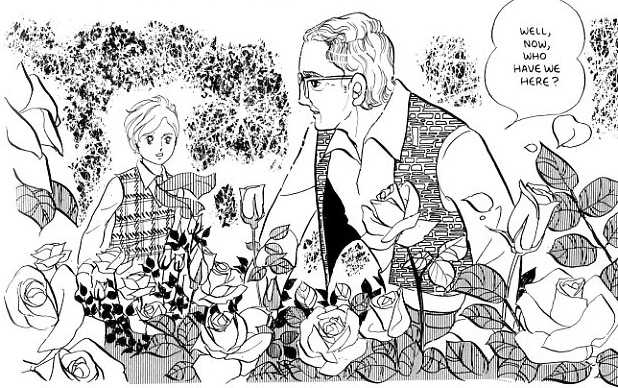

On the next page the same woman is upright, but no more located — in fact, the first image is a close-up of her thinking about her dreams, and the next is a hazy shot of the back of some guys head. In the next panel we do get some sense of where we are, sort of; the woman is talking to a standard-issue fortune-teller in a room which recedes into blackness.

Then for the next two pages we swoop into the crystal ball, seeing a vision again of the back of the man’s head as he stands over the woman, now dead, lying face down.

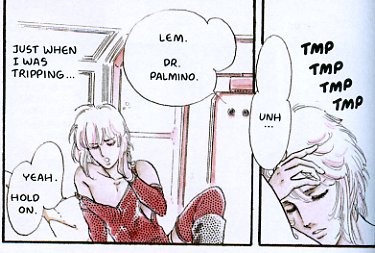

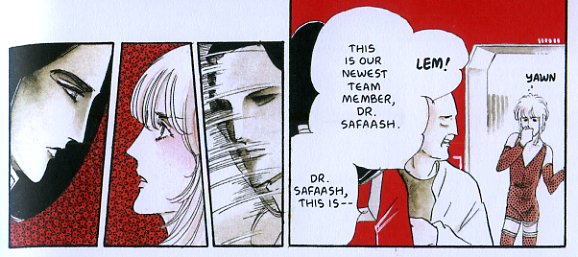

It’s the next page which pushes the refusal to tell us where on earth we are right over the top — not least because we’re suddenly not on earth. Instead, we exchange the generic fantasy setting for a generic space setting; the woman we saw before is on a space station, where she goes downstairs to meet back-of-head guy. The two recognize each other, as we do, from their dreams.

Again, from the perspective of a conventional, well-made story, this is a disaster. Both the fantasy milieu and the sf milieu are pure genre kitsch. The two main characters, Lem and Gadan Safaash, are equally ill-defined — we know nothing about them except that Gadan is literally the man of Lem’s dreams. Over the next couple of pages, Hagio does give them a little banter; Lem is a scientific rationalist, Gadan is a scientist but also a priest who believes in Spriritual Truths, blah blah blah. Trite new age nonsense joins trite sf and fantasy and romance clichés in a giant ridiculous ball of nonsense.

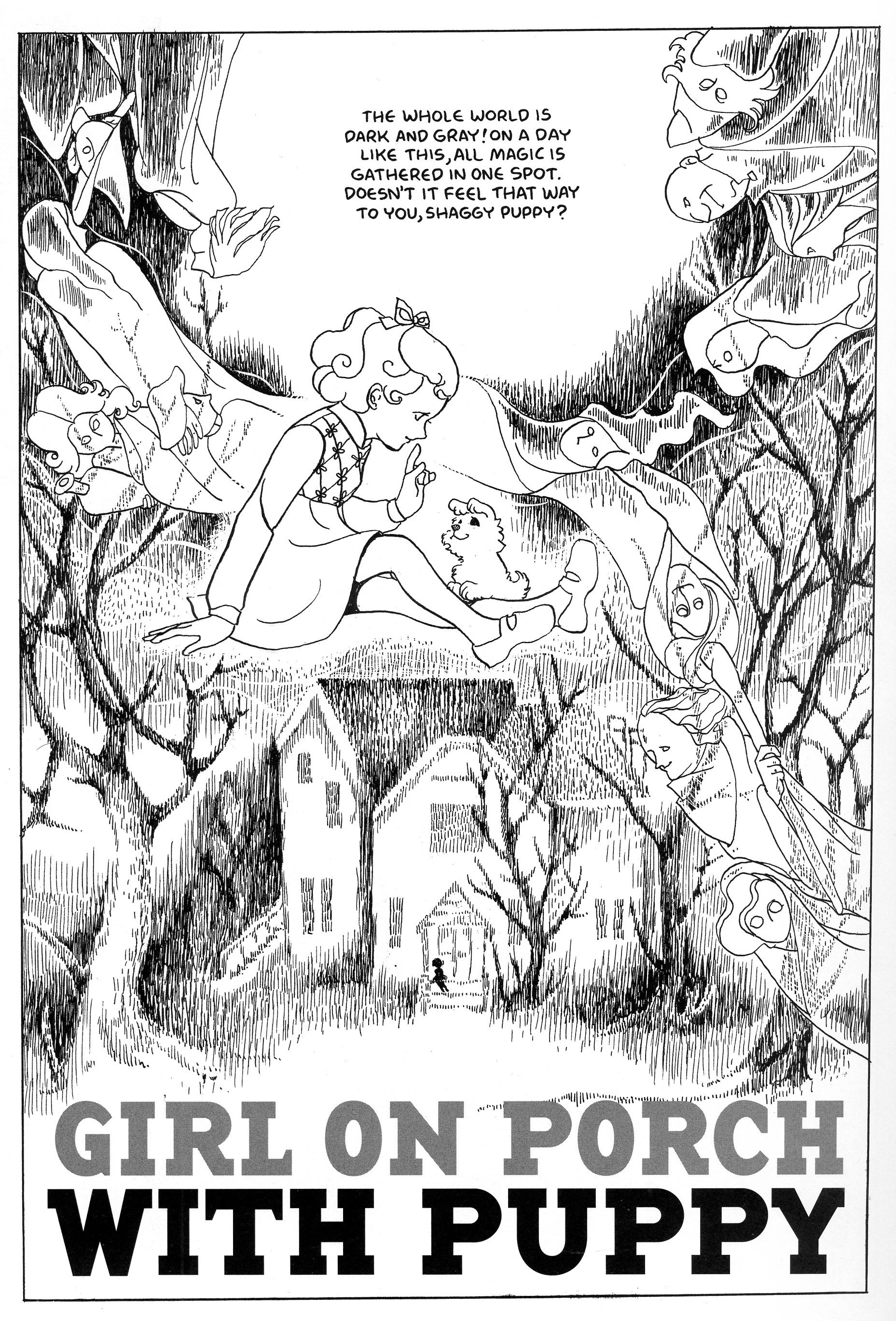

But…you get that much nonsense in half a dozen pages, and it starts to look deliberate. It’s one thing to have a bland fantasy setting; it’s another to leap from bland setting to bland setting like some sort of aphasiac, amphetamine-charged bunny. Contrasting the fantasy with the sf and both with the insistent discussion of romantic dreams and New Age gobbledygook — the world Hagio is setting up is so friable is starts to disintegrate as soon as you even think about touching it.

The tell, here, is Lem herself…or himself. After the switch from fantasy to sf, other characters refer to Lem, who initially seems to be the woman in the first pages, as a man. Shortly thereafter we learn that “while Lem manifests as male…he in fact has xx chromosomes.” The gender swap is keyed in part to the difference between fantasy (often coded female) and sf (often coded male). And it’s also enabled by the comics medium itself; because the drawings are iconic, cartoon representations, we can’t, in fact, know Lem’s gender until someone in the narrative tells us what it is.

Thus, gender becomes both a function of genre and of artistic convention, pointing to and determined by shared fantasies and by Hagio’s individual artistic fiat. The universe and individual identity are linked, and both are arbitrary, not in the sense of being stochastic, but in the sense of being provisional. This is a world that is coming into being with each panel — and fades out in the gutters. Thus, when we finally see back-of-head guy’s face, you get the sense that it’s actually being created for the first time as you watch. This impression is only heightened by the way that Hagio cheekily uses the speech bubble to white his face out in the previous panel.

Over the next few pages, Lem and Gadan talk about their mutual dream, in which they both see Lem lying face down at Gadan’s feet. Gadan tries to explain it by arguing that “I think some kind of shock has created a wound in the space-time you and I occupy, forcing us to repeat the same experience.” Lem suggests this is “Like some kind of psychological trauma in space-time…” moments before the land-rover the two are driving falls into a pit. Luckily, though Lem is injured, he is not killed — and the two speculate that space-time is trying to heal its own wound by turning Lem into a hermaphrodite, breaking the cycle of repetition and death. The moral for Hagio couldn’t be much more clear — gender drift and same-sex desire comes out of trauma and heals it, the arbitrary universe of the psyche stitched together by unconventional love. Fade out, the end, as Lem and Gadan kiss each other.

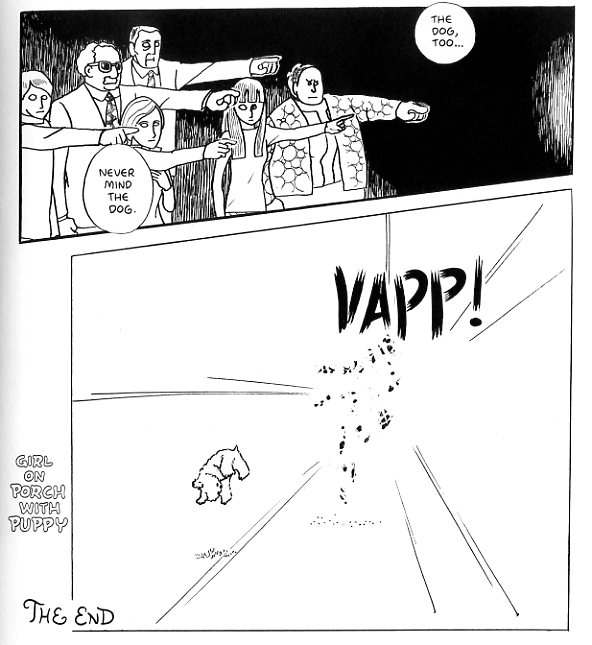

And then things get weird. Because the comic refuses to end. Suddenly, it shifts back to the fantasy setting. Lem is now Princess Palio, Driven by dreams, she saves a handsome prisoner (Gadan)…and said prisoner turns around and kills her for her pains. Except then Gadan from the future comes back as a spirit and kills his former self, who ends up lying face up before Princess Palio. And then we shift back to the sf setting, where Lem and Gadan are somewhere (falling into the same pit as before? in a different accident?), only this time Gadan is killed. And we end with Gadan in his spacesuit drifting through black space with Princess Palio above him.

There are so many ways this doesn’t make sense it’s difficult to count them all. In the first place, if the fantasy setting was supposed to be the beginning of the cycle of trauma, why is Palio already having dreams about back-of-head guy before he shows up? And is the bit where Gadan and Lem survive the accident itself a dream, or do they have a second accident, or what? And are we really supposed to admire and/or feel sorry for back-of-head-fantasy guy after he cruelly stabs his rescuer for pretty much no reason except that he’s a jerk?

The last is perhaps the most pertinent question if we accept that the story is about trauma and abuse, and that it’s characters are not characters at all, but stand-ins. The generic fantasy setting isn’t real; the generic sf setting isn’t real; Lem isn’t real and neither is Gadan. But the primal scene of trauma is real; the knot of love and violence that repeats and repeats, propounding different resolutions but never resolving. The story says, if I were a man he wouldn’t hurt me; if we were in a different world he wouldn’t hurt me; if he understood he would regret what he did and try to make it right; if we really knew each other, face to face, he wouldn’t hurt me. But the happy endings turn into nonsense; even the abuser’s change of heart doesn’t lead to love, but only to more pain. The end is not the kiss of reconciliation. Instead, “Time sees the same dream. It sees the same dream again and again. This dream shall never fade. Time goes on weeping…drunken, singing as it sinks down to the depths of the dream.”

In the first few stories in this book, Hagio deploys conventions and clichés clumsily. She deploys them clumsily here as well…but her drunken stagger is its own kind of grace. The trite wish fulfillment is so poorly constructed it disintegrates. The very glibness of the medium, the way that comics can so easily evoke genre with the image of a sword or a spaceship, is turned back on itself. We’re left with stupid tropes floating in emptiness, and the story we’re told, the face we see, drops away to reveal a space like a wound.

____________

My apologies for the places where the scan colors are screwed up, by the by. If you want to see the art the way it’s supposed to be, I’d urge you to buy the book!