In our last chapter, we focused on the Western, particularly as presented in the cheap, pamphlet-formatted magazines known as dime novels. Of course, westerns weren’t the dime novel’s sole adventure genre: tales of pirates, spies, and detectives abounded; the most durable dime novel hero of all was probably Nick Carter, Detective– his adventures ran, in various media, from 1886 to the 1990’s.

Before leaving the Dime western, however, I wish to dwell on one of its heroes who was a precursor of the modern, cross-media, branded intellectual property character: Buffalo Bill.

William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody (1846–1917) was an authentic frontiersman, whose adventures were written up by Ned Buntline (1813–1886), the writer often called “the man who invented the West” , in the 1869 serial Buffalo Bill, King of the Border Men for the New York Weekly. The tale was enough of a success to inspire a hit theatrical adaptation in 1872.

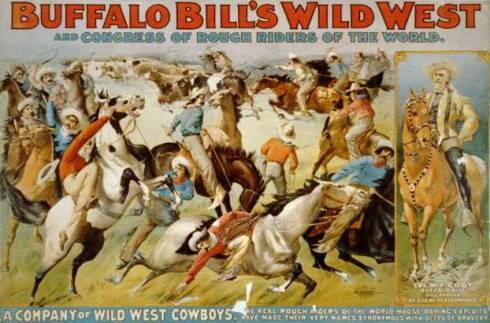

Cody was much taken by the play, and agreed to star in person in another Buntline-inked production, The Scouts of the Plains; or, Red Deviltry as it is, co-starring Texas Jack and Wild Bill Hickock. After a very profitable ten-year tour, Cody struck out on his own in 1883 by organising his own extravaganza, part drama, part circus, part rodeo, all Western, all sensational: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

The show was a colossal hit such as the world had never seen. It toured not only the U.S.A., but also Europe, selling over two million tickets in its first London run. Buffalo Bill was, probably, the first true international celebrity entertainer.

He was also what we’d call a brand. Enormous sums were made from merchandising Bill and his associates’ images; toys, films, crockery bore his stamp; he is thus the forerunner to such other “hero-brands” as Tarzan, Batman, or the Star Wars crew.

A Buffalo Bill toy set from 1903. Bill certainly understood merchandising…

Of course, Buffalo Bill fiction continued to pour onto the newsstands — it’s estimated that, without even counting unauthorized pirate books, some 557 novels chronicled his supposed adventures. Of these, 121 were written by Prentiss Ingraham (1843–1904) — who also happened to be the press agent for the Wild West Show.

Long before the phrase was coined, Ingraham perfectly understood the concept of “media synergy.” Thus, just before the show was due to open at the Chicago World’s fair in 1892, he wrote and had released nine new Buffalo Bill novels. Six of these actually dealt with the show itself — publicity and product placement.

Ingraham also understood the value of “spin-off” product: he promoted the fictional adventures of Wild West co-stars Buck Taylor, Nate Salsbury, and Annie Oakley.

He would have been perfectly at home in today’s superhero business ecology.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show reminds us that, though this series of articles has concentrated on the printed word, there were of course many other vectors of popular culture, such as songs, circuses, and the theater. In nineteenth century America, the latter was decidedly democratic in spirit; and the masses clutched to them as their own the plays of William Shakespeare. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted:

There is hardly a pioneer’s hut which does not contain a few odd volumes of Shakespeare. I remember reading the feudal drama of Henry V for the first time in a log cabin.

Such was the popular mania for the Bard that in 1849, a riot in New York over competing productions of Macbeth left 25 dead.

I don’t think it too far-fetched to speculate that early American Shakespeare productions, as mediated by melodrama, are another distant root of the superhero. Consider the many conventions the superhero tale shares with Elizabethan theater: lively heroes and villains, secret identities, disguises that are always effective, fight scenes complete with colorful speeches, and men in tights!

( I was struck by this theory while watching the first X-Men film, with its glorious use of two of Britain’s greatest Shakespearian actors– Patrick Stewart as Professor X, and Ian McKellan as the arch-villain Magneto.)

The dime novel went into decline at the turn of the last century, for various reasons.

Despite its name, the dime novel generally cost a nickel (5 cents) rather than a dime (10 cents). Even in 1900 dollars, that didn’t leave much of a profit margin. Furthermore, by that date the dime novels were almost entirely pitched at children and adolescents, a demographic that had little in the way of spending power: thus, this was a medium unattractive to advertisers. (The same problem would bedevil comic books, especially after the mid-1950s, when the Comics Code strictly regulated advertising.)

There were also fresh rivals for the young person’s pennies; most notably the new mass medium of film. Your leisure nickel could now buy you all the excitement of the movies; why spend it on musty, hacked-out pamphlets?

Meanwhile, a writer turned book packager, Edward Stratmeyer (1862-1930), launched series after series of inexpensive books targeting young people: theRover Boys, Tom Swift, the Bobbsey Twins, the Hardy Boys. These were ghost-written by multiple authors and published under house names, such as Victor Appleton. Their success was phenomenal — in a 1922 study, it was estimated that the Stratmeyer Syndicate published the majority of children’s books sold.

The books continue to sell well to this day.

(These wholesome adventures attracted what would strike us as bizarrely extreme hostility from educators. The New York Public Library’s chief children’s librarian, Anne Caroll Moore, in 1906 boasted of purging them from the system she oversaw.)

Stratmeyer’s innovations– concentrating on series, farming out manuscripts to freelance writers — would become standard procedure for comic books.

The Coming of the Pulps

The successor to the dime novel was the pulp magazine.

Publisher Frank Munsey (1896 — 1925) saw the writing on the wall. He decided to convert his dime novel line to a new format, thicker and more expensive, aimed at an adult audience that still craved escapist adventure. Because they were printed on the cheapest, roughest paper available– so-called ‘pulp,’ these magazines came to be called pulps.

His Munsey’s (from 1889), Argosy (from 1888) and All-Story (from 1905) magazines were immediate hits. They were anthologies featuring adventure tales set the world over– in the far west, Africa, the Seven Seas, and even on other planets.

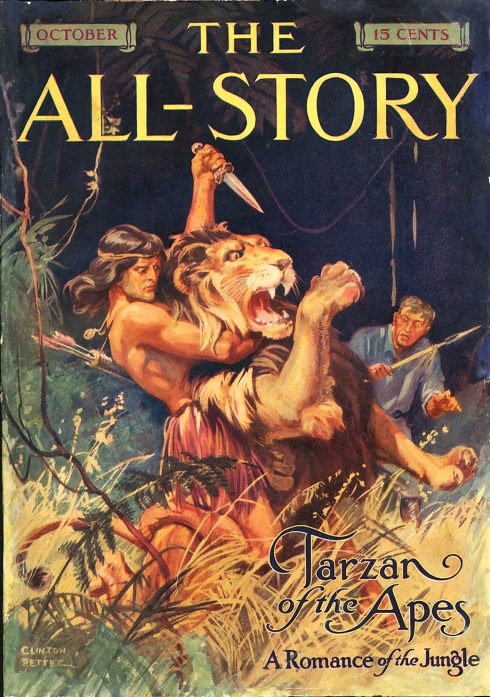

Among the most popular — and lasting — writers Munsey’s pulps discovered was Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875 — 1950), whose extra-planetary adventure romance Under the Moons of Mars was serialised by All-Story in 1912.

It was the first of the popular John Carter of Mars tales, featuring an American soldier mystically transported to the Red Planet, where he battles an array of fierce aliens. The lower gravity of Mars gives his Earth muscles super-strength — a detail later adopted by the creators of Superman for their hero.

Burroughs later that same year of 1912 introduced arguably the most famous adventure hero in pop history, Tarzan of the Apes, again in All-Story (see image at top of this column.)

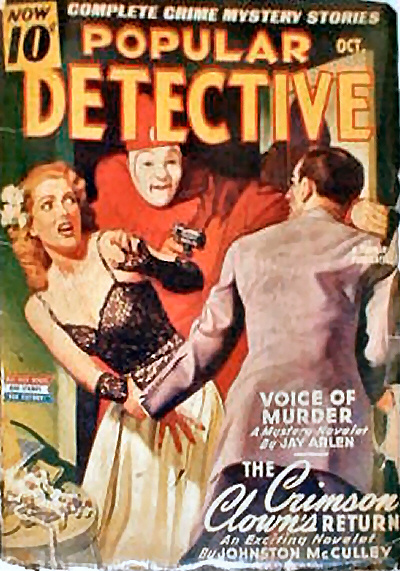

All-Story caught lightning in a bottle once more in 1919, when it published ‘The Curse of Capistrano’ by Johnston McCulley (1883-1958), the first adventure of Zorro.

Zorro is worth dwelling on for several reasons.

In Spanish colonial California, young aristocrat Don Diego de la Vega appears to be a silly young fop; secretly, however, he roams the countryside as the dashing masked swordsman known as Zorro (‘the Fox’), fighting injustice and oppression with flashing blades and sharp wits.

This iteration of the secret hero (probably based on the Scarlet Pimpernel), i.e. a seemingly harmless playboy type hiding a brilliant fighter for justice, was to be repeated many times in super-hero lit; in the pulps (the Shadow, the Phantom Detective, McCulley’s own the Crimson Clown) and in the comics (Batman, the Clock, Mr Scarlet.)

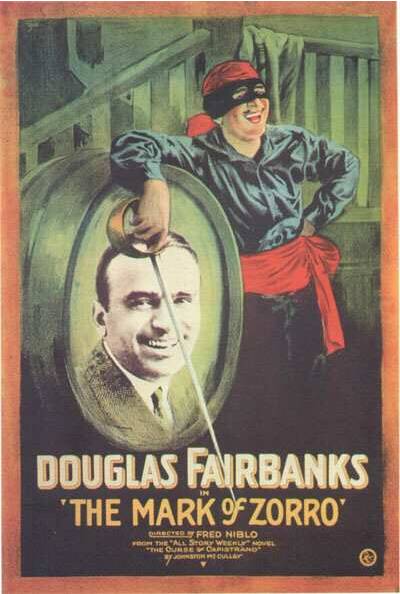

And in 1920, McCulley’s novel was filmed starring the two biggest movie stars in America, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, as The Mark of Zorro.

This was another sign that the superhero spanned various media long before he appeared in comic books — magazines, books, films, radio, comic strips.

In the three decades from 1920, the pulps proliferated– and specialised. Magazines were devoted to every pop genre and sub-genre under the sun: the reader browsed a fabulous junkshop of thrills and chills.

Crime: Black Mask, Dime Detective.

Horror: Weird Tales, Horror Stories.

Science fiction: Marvel Tales, Amazing Stories, Astounding, Planet Stories.

Aviation: Flying Aces, G-8 and his Battle Aces.

Westerns: All-Western Magazine, Blue Ribbon Western.

Romance: Ardent Love, Love Story Magazine.

There were even strange genre hybrids. Crime + soft porn = Spicy Detective Stories. Western + romance = Ranch Romance.

And there were the ‘character pulps’.

These were magazines dedicated to a single character, and many of these were superheroes.

Harvesters of the Bitter Fruit

Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!

The Shadow was introduced in 1929 in a one-off story. Street & Smith, its publisher, revived the character in 1930 for its radio show, Detective Story Hour, and followed this the next year with a dedicated magazine. The latter would continue until 1949, featuring 325 tales ascribed to house pseudonym “Maxwell Grant” — most of the novels were in fact written by Walter Gibson (1897-1985).

Playboy Lamont Cranston is the mysterious scourge of the underworld, theShadow. With blazing pistols and mysterious powers (the ability to ‘cloud men’s minds’), he ruthlessly opposes gangsters and such adversaries as Shiwan Khan and the Prince of Evil– teaching them the truth of his motto:

The weed of crime bears bitter fruit. Crime does not pay… the Shadow knows!

Poster for the Shadow serial. Serial films often featured superheroes, both from the pulps and the comics.

It is especially as a radio show that the Shadow achieved success (Orson Welles was one of the main interpreters of the title role.) Radio even spawned its own original superhero: The Green Hornet.

A more savage rival to the shadow was the Spider (fl.1933-1944).

The Spider — principally written by Norvell Page (1904–1961) under the pen name ‘Grant Stockbridge’ — was another idle playboy-turned-vigilante, but whose bloodlust seemed unslakeable. As historian Jim Steranko put it, “His idea of mercy was a bullet between the eyes instead of in the stomach”. His descendants in the superhero line are the ‘grim and gritty’ killers that flourished in the 198?s and ’90s, such as the Punisher, Grifter, or Vigilante. Like them, he was hated and hunted by police and criminals alike.

Another in the Shadow/Spider mold, but more genteel, was Richard Curtis Van Loan, a.k.a the Phantom Detective (fl.1933–1953).

This dapper sleuth, though no slouch when violence threatened, was more of a true cerebral detective than his pulp colleagues, and he worked closely with the police: a new twist for the superhero, who had traditionally been an outsider. As the illustration above shows, the Phantom is content with a wee domino mask for a disguise, which fools everyone; a convention still current in superhero comics.

The Avenger, The Whisperer, Captain Zero, The Black Hood, The Cobra, Moon Man…the list of pulp superheroes stretches on. We might linger on one, the Black Bat– the illustration below shows why:

It would appear that this was the inspiration (to use a polite word) for the comic-book superhero Batman…but the latter first appeared in May 1939, while the Black Bat premiered in July of that year. A case of coincidence that provoked a testy exchange of lawyers’ letters and a live-and-let-live arrangement. (Note, however, that Batman later adopted the Black Bat‘s fin-lined gauntlets in his costume.)

But next to the Shadow, the king of pulp superheroes was Doc Savage, the Man of Bronze.

However, we’ll leave discussion of Doc for the next installment of this series; note however, the word coined by Street and Smith (publisher of The Shadowand Doc Savage) to describe this sort of character:

super-hero, the first time this appellation appears.

Blinded with Science

Some of the best (and occasionally worst) of the pulps were the science-fiction magazines. (Indeed, one of the last survivors of the pulp age — much transformed in format — is the SF digest Analog, the renamed Astounding Science Fiction.)

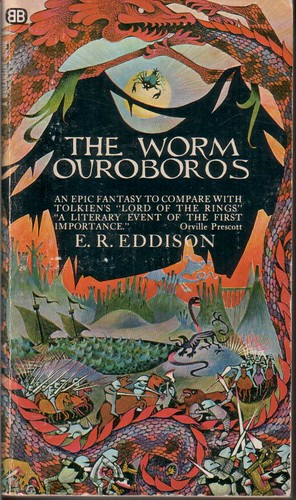

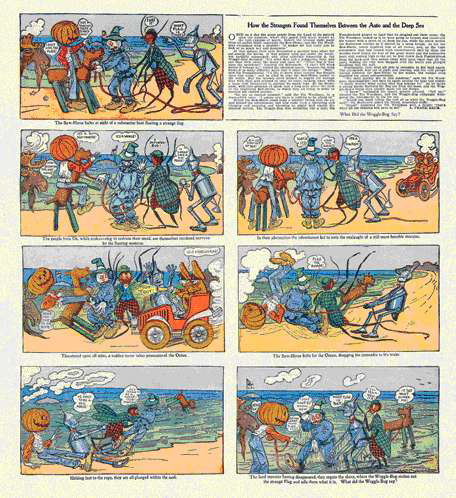

And the type of science-fiction that permeates superhero comics isn’t the cerebral, literate fare of Olaf Stapledon or of J.G.Ballard– no, it’s the extravagant ‘space opera’ of E.E.’Doc’ Smith (1890–1965) and his fellow writers at Amazing Stories.

Smith’s Lensman series (1937) begins with two galaxies colliding, and builds from there. Exploding planets! Space Pirates! Intergalactic empires at war! And policing it all is the corps of the Lensmen, supermen armed with the Lens, an invincible energy weapon.

(The Lensmen would inspire the space-faring superhero group the Green Lantern Corps in DC’s Green Lantern comics, and the Lanterns’ power rings obviously derive from the Lens.)

Another space opera with superheroic overtones was penned by Jack Williamson (1908–2006), The Legion of Space (1934)– a possible inspiration for DC comics’ Legion of Superheroes.

Space Legionaires facing a bit of a sticky wicket

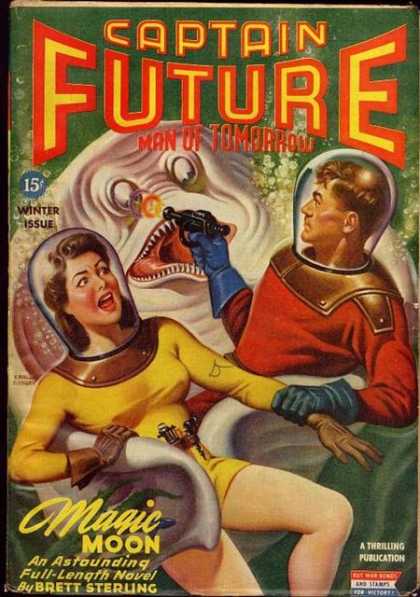

This is plausible, because the main early writer of the Legion of Superheroes wasEdmond Hamilton, also the author of the Williamson-influenced Captain Future pulp series; Captain Future was created by Mort Weisinger, the editor of the Superboy comic in which the Legion of Superheroes first appeared.

;

As this shows, the links between comics and the pulps were close; next installment will illustrate just how close.

Next: Reign of the Superman