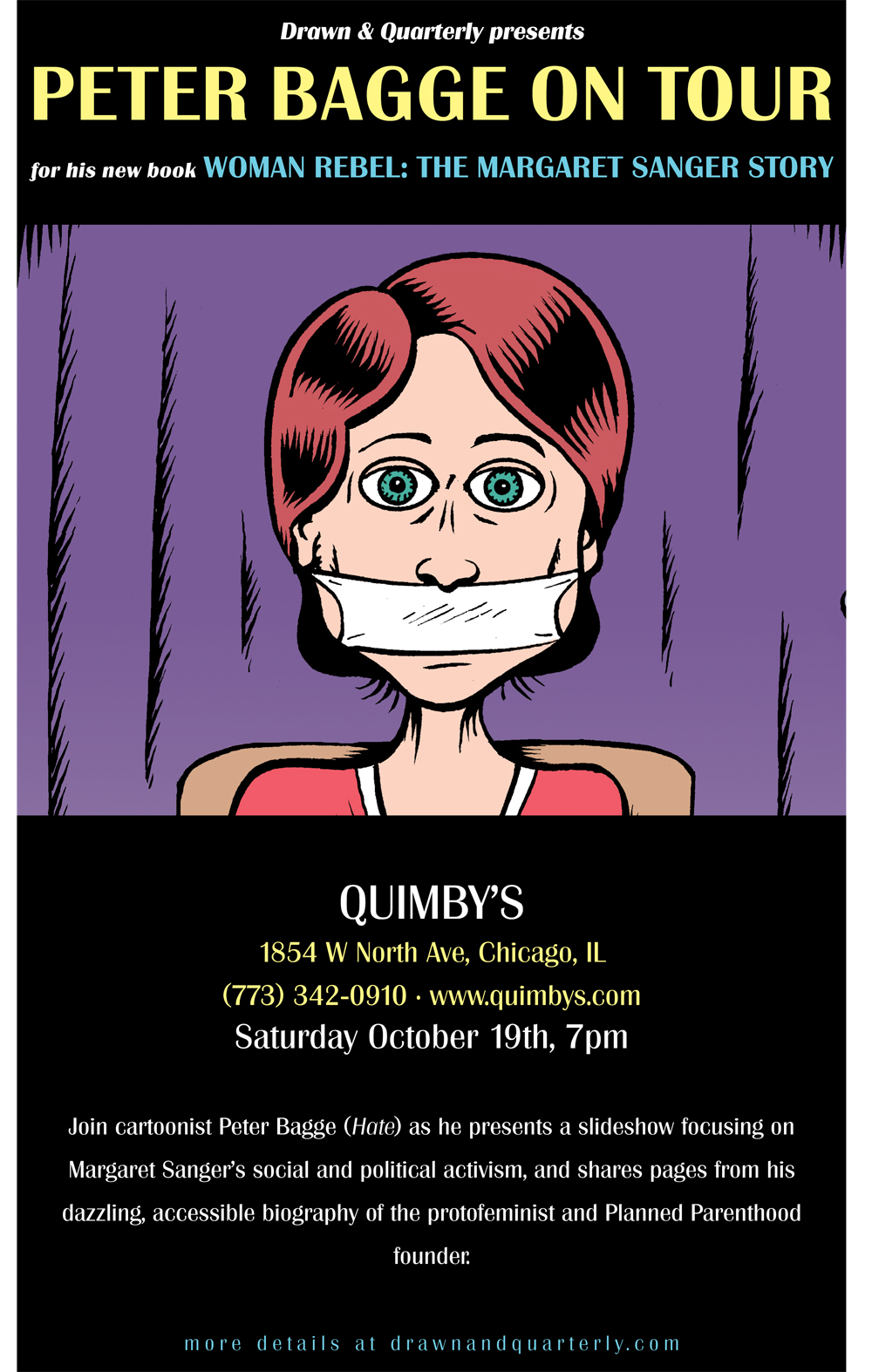

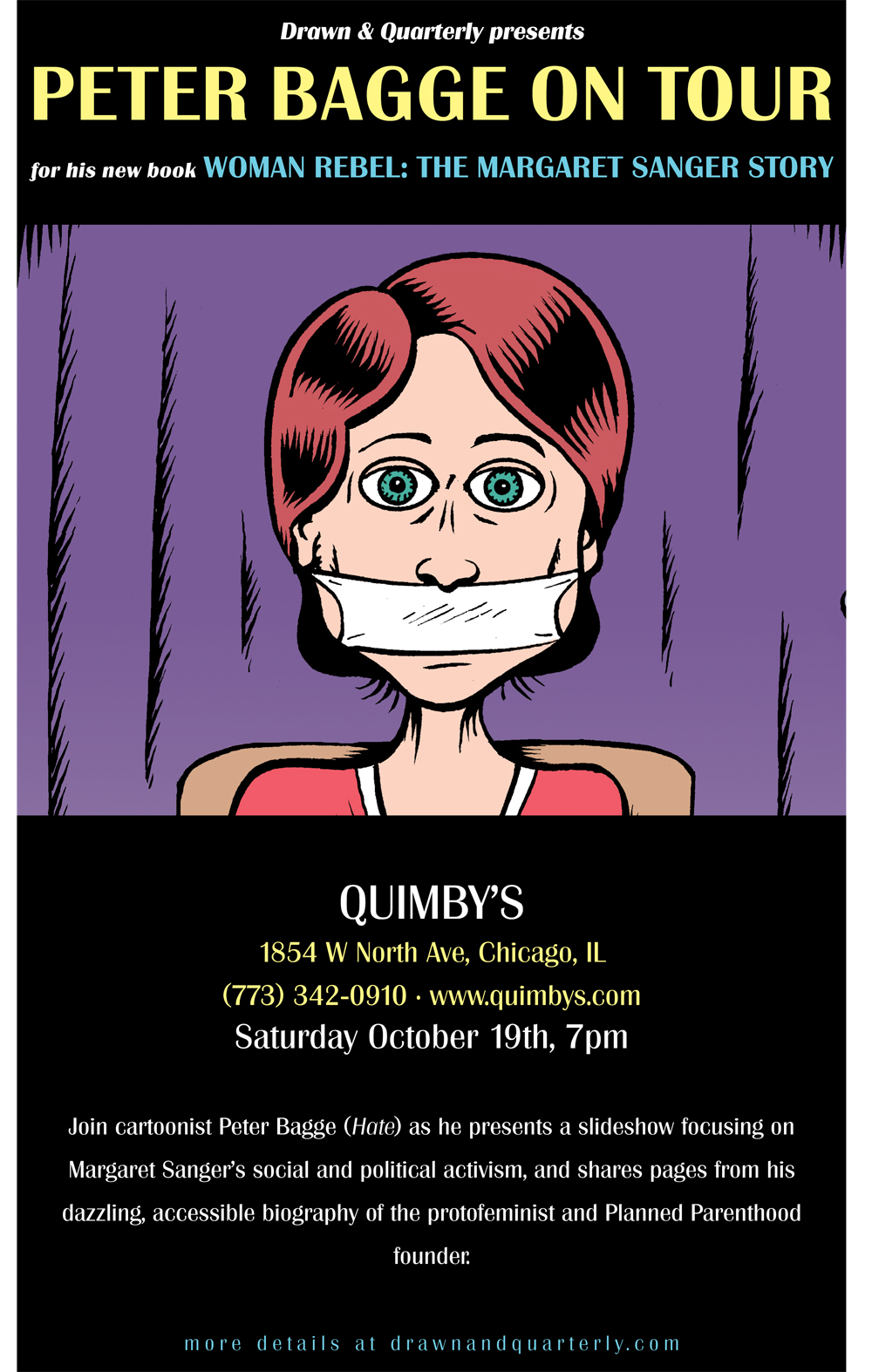

I first came to hear of Peter Bagge’s Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story through reading Sarah Boxer’s review at TCJ.com; an article which I approached with a mind to find articles to include in my Best Online Comics Criticism list for 2014.

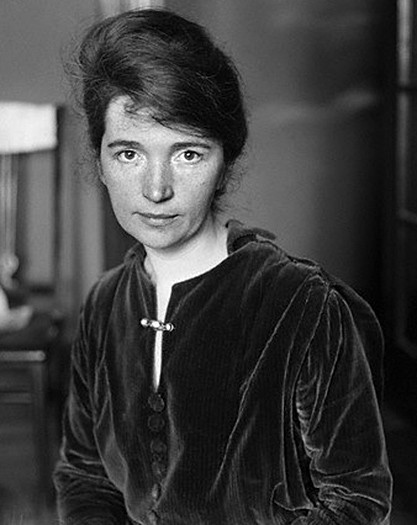

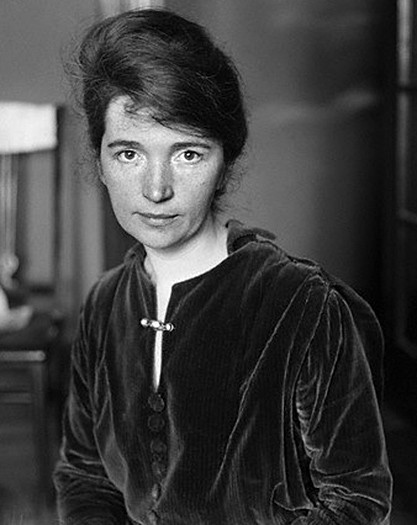

Boxer’s article is congenial and engaging without getting into too many details. What emerges from it is a picture of Sanger as a tireless campaigner for women’s rights and their access to birth control; an individual with the ferocity and disposition of a saint who “martyred” her mind and body on the altars of alcohol and Demerol for the cause.

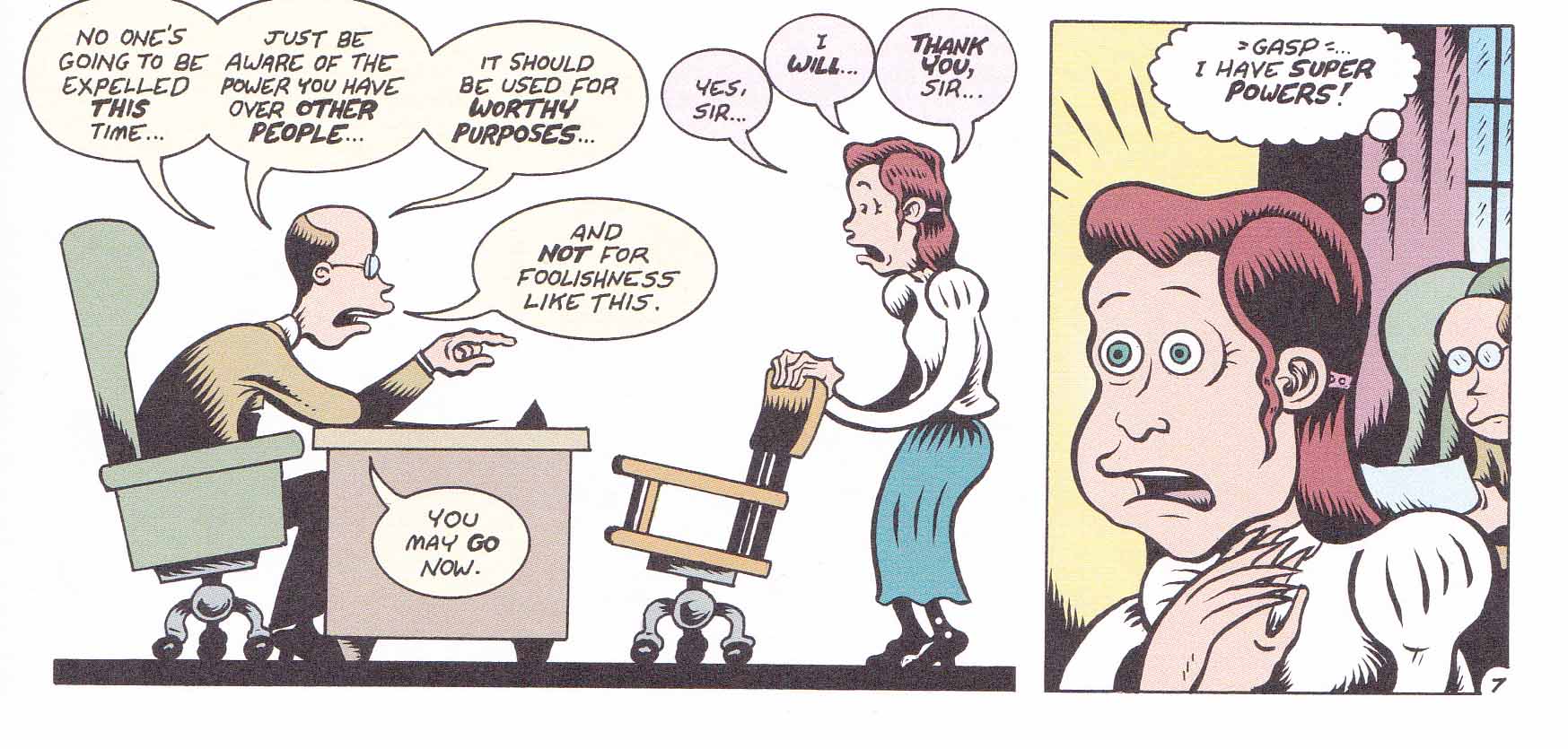

Boxer’s review takes its cue from an episode near the beginning of Bagge’s biography.

In Boxer’s words, Sanger was a

“…true hero, or a super-hero, if you will.” She was a “ball of energy, intelligence, and fury. She was also a proponent of free love…she practiced it (while married) with the writer H. G. Wells.”

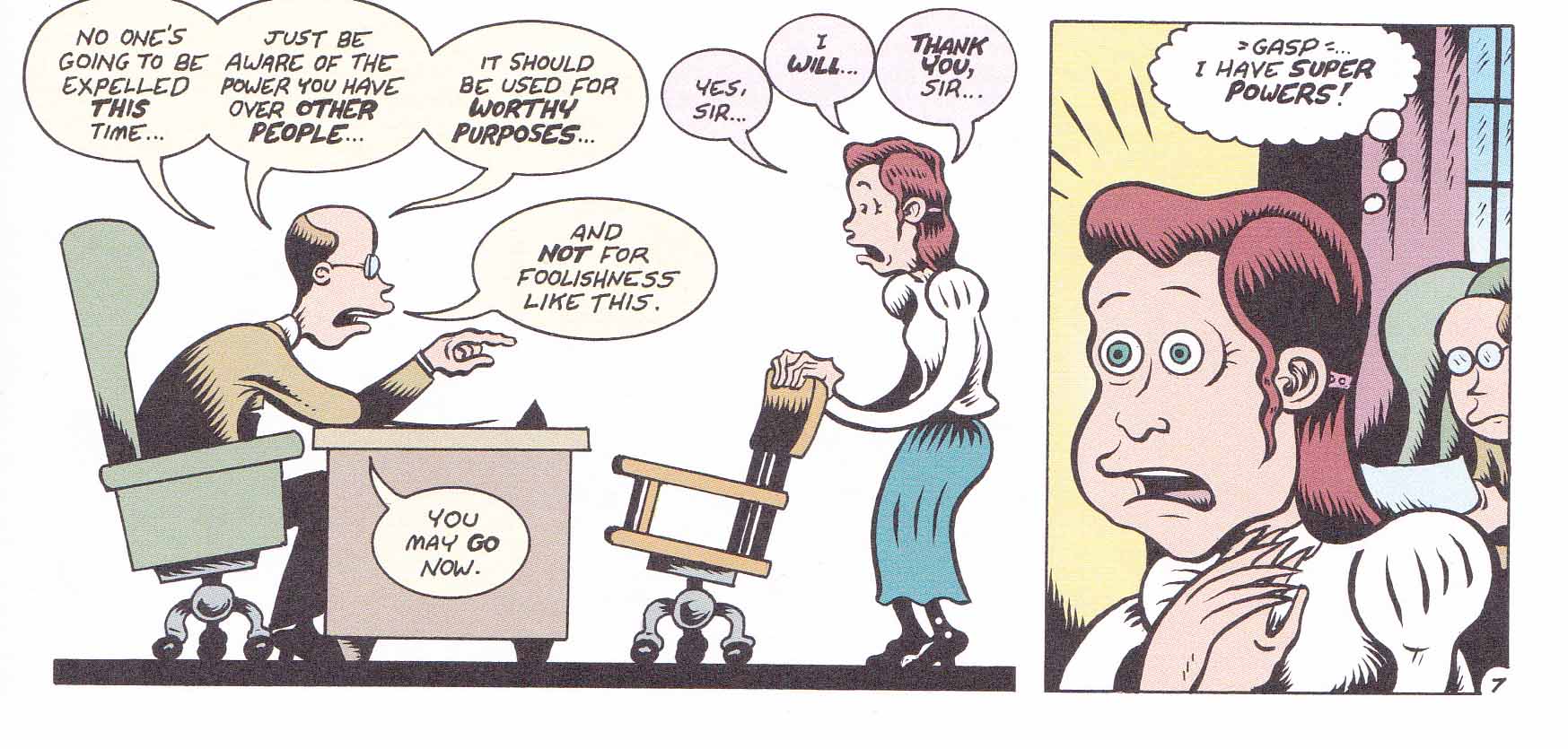

And then there’s her She-Hulk like rage (and morally correct disposition):

“Censorship was Sanger’s goad to battle. From this point on in Woman Rebel, it seems that everyone’s eyes are bloodshot and crossed with rage, and you can see rubbery limbs swinging wildly on many a page. Sanger was at war with practically everyone, even those on her side.“

A look at Boxer’s conclusion reveals her train of thought:

“Woman Rebel, though on one level functioning as a superhero comic, also fits onto a certain growing shelf of books with other admirable short biographies…[Bagge] has transformed Sanger into a real live superhero who will herself live to see another day.”

The images produced in the review suggest a kind of absurdist, Far Side version of Sanger’s life. But more than this, there is the air of only marginal fallibility which is the hallmark of the superhero genre. While Tony Stark is allowed to be an alcoholic, Batman will probably still save the homeless man living in an alley way even if he’s suffering from alcohol-induced dementia; Superman rarely deploys his heat vision to sterilize children

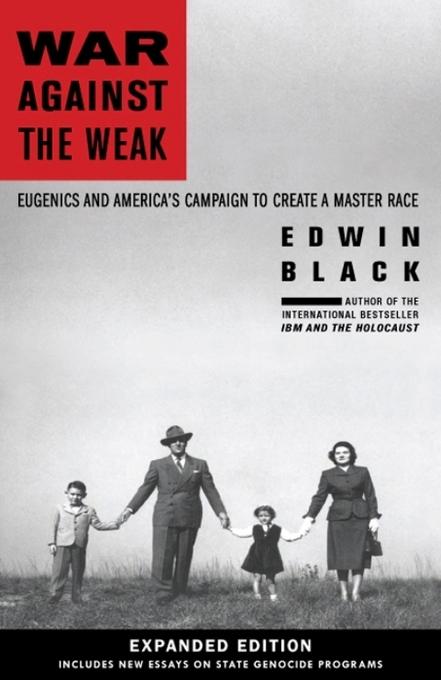

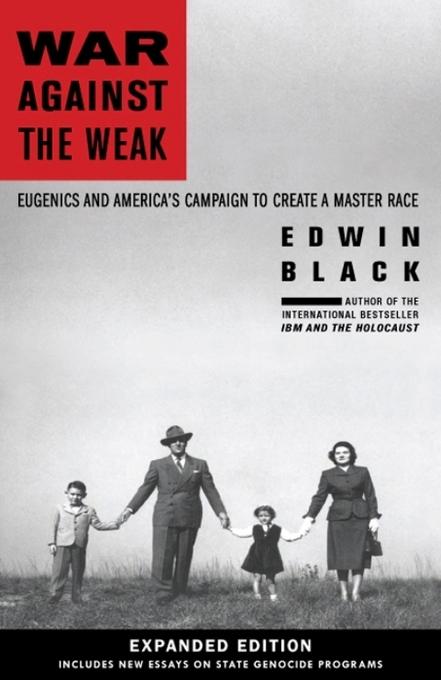

I had almost forgotten another aspect of the Sanger story, one which I first came to know about nearly a decade ago. That story comes from Edwin Black’s book, War Against the Weak (2003) which charts the rise of the eugenics movement in America (and then abroad). Edwin Black has a short chapter on Margaret Sanger in his book. He approaches the topic with extreme caution and his introduction comes with a prominent disclaimer:

“Opponents of a woman’s right to choose could easily seize upon Margaret Sanger’s eugenic rhetoric to discredit the admirable work of Planned Parenthood today; I oppose such misuse.”

He also pre-emptively loads the section on Sanger with a long list of her achievements and descriptions of her admirable character. His reasons for doing so become quite clear once the reader reaches the chapter on “Birth Control” in his book. Read in isolation, it is a devastating portrait of a figure who, from the tone of Boxer’s review, seems more akin to the Mary Poppins (she could be quite strict and disagreeable) of Birth Control.

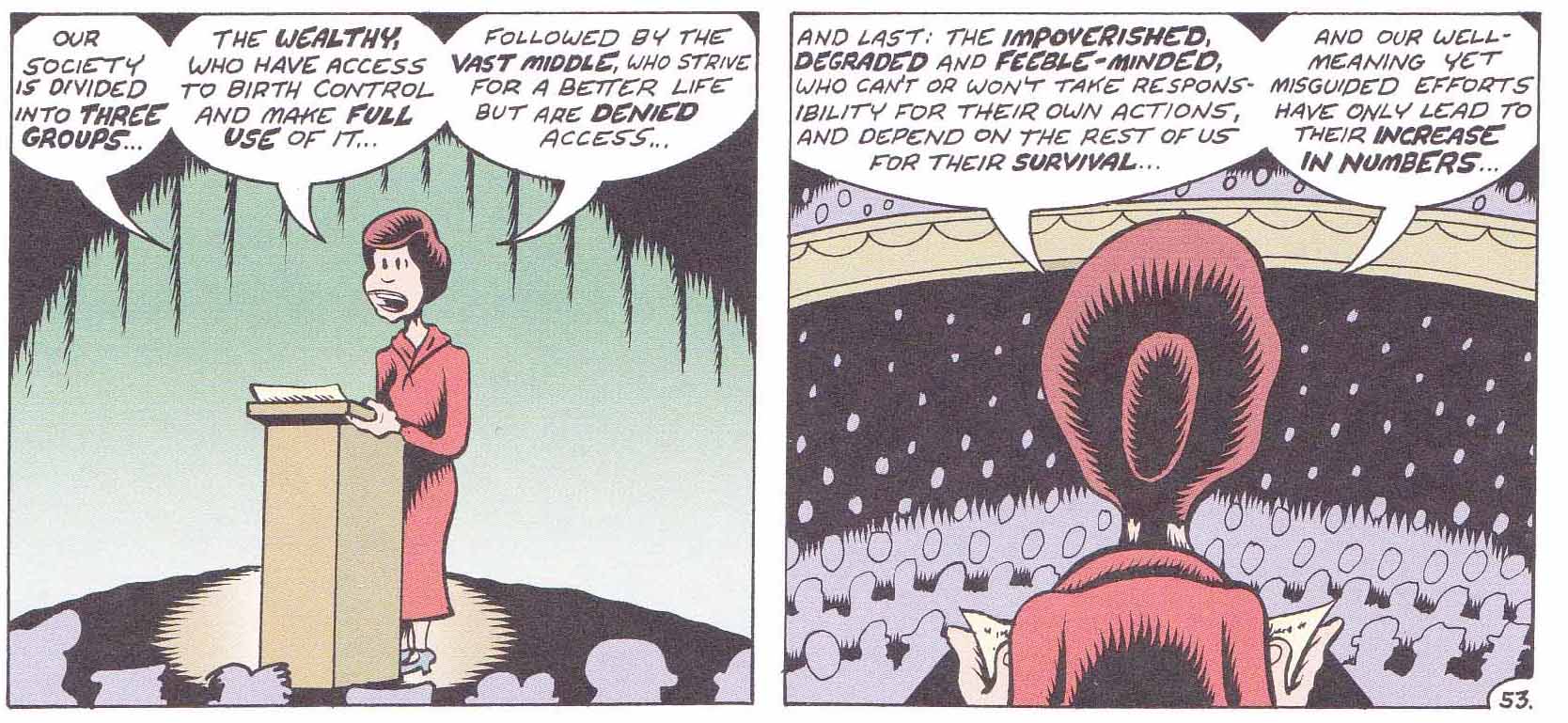

Black enumerates an appalling record of Sanger’s ideas through the early 20th century. Here are some facts and extracts from Black’s chapter on Sanger:

(1) She saw the “obstruction of birth control as a multi-tiered injustice” of which one was the “overall menace of social defectives plaguing society.”

(2) She “expressed her own sense of ancestral self-worth in the finest eugenic tradition.”

(3) She almost named her new movement, “Neo-Malthusianism” and was an “outspoken Social Darwinist”. Her book, The Pivot of Civilization (1922), contains a chapter titled “The Cruelty of Charity”. The epigraph of that chapter was from Herbert Spencer himself and it read:

“Fostering the good-for-nothing at the expense of the good is an extreme cruelty. It is a deliberate storing up of miseries for future generations. There is no greater curse to posterity than that of bequeathing them an increasing population of imbeciles.”

(4) From Sanger herself Black quotes:

“Organized charity itself is the symptom of a malignant social disease…the surest sign that out our civilization has bred, is breeding and is perpetuating constantly increasing numbers of defectives, delinquents and dependents.”

“Such philanthropy …encourages the healthier and more normal sections of the world to shoulder the burden of unthinking and indiscriminate fecundity of others; which brings with it, as I think the reader must agree, a dead weight of human waste.”

“The most serious charge that can be brought against modern ‘benevolence’ is that it encourages the perpetuation of defectives, delinquents and dependents. These are the most dangerous elements in the world community, the most devastating curse on human progress and expression.”

(5) “Sanger…listed eight official aims for her new organization, the American Birth Control League. The fourth aim was “sterilization of the insane and feebleminded and the encouragement of this operation upon those afflicted with inherited or transmissible diseases…”

(6) Though she was not thought to be a racist, she allied herself with Lothrop Stoddard, author of The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy which warned that “if white civilization goes down, the white race is irretrievably ruined. It will be swamped by the triumphant colored races, who obliterate the white man by elimination or absorption.”

[In the interest of balance, I will mention this site recounting Sanger’s Negro Project which provides a dissent concerning her degree of racial discrimination. It is, however, quite clearly a pro-life site and needs to be read with proper caution. Some historical facts earlier in the article may, however, be of interest. Also see Anna Holley and Carl M. Cannon on the misuse of Sanger on this controversial issue.]

Sanger was probably an equal opportunity eugenicist who esteemed Whites, Jews and Blacks alike as long as they had good genes. I guess humanity is safe as long as there is a consistent definition of those “good genes”.

While Sanger held to these views well beyond the golden age of the eugenics movement, one mark in her favor is that she never held to eugenicide or eugenics-inspired euthanasia. Planned Parenthood is no doubt relieved by this.

* * *

I have only a cursory interest in the life of Margaret Sanger. Apart from the books mentioned above, I have only read Sanger’s The Pivot of Civilization and a short but glowing prose biography. From the perspective of a Sanger neophyte, these uncomfortable facts merely lead to more questions about whether these observations and extracts are accurate, and whether they have been taken out of context.

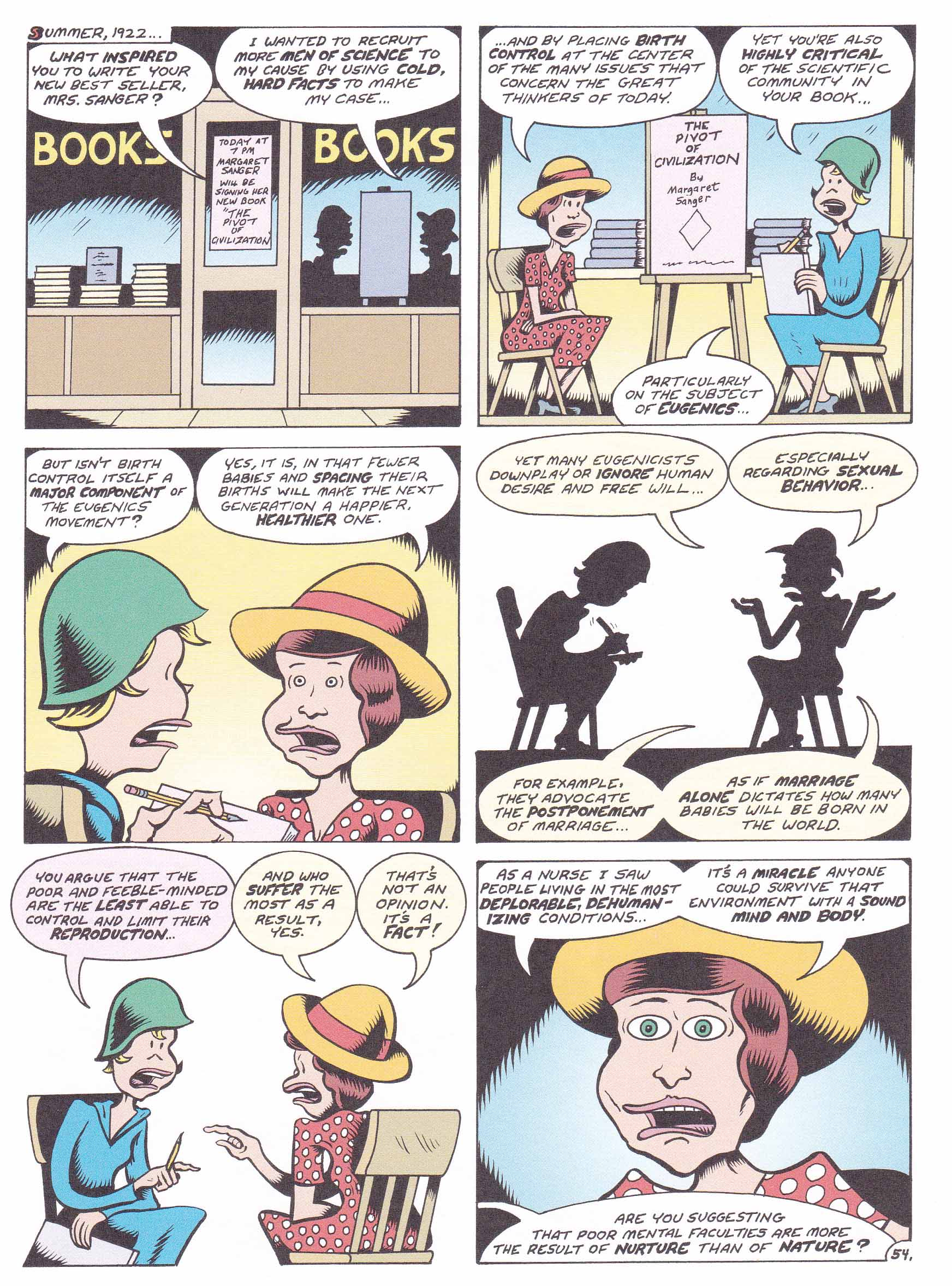

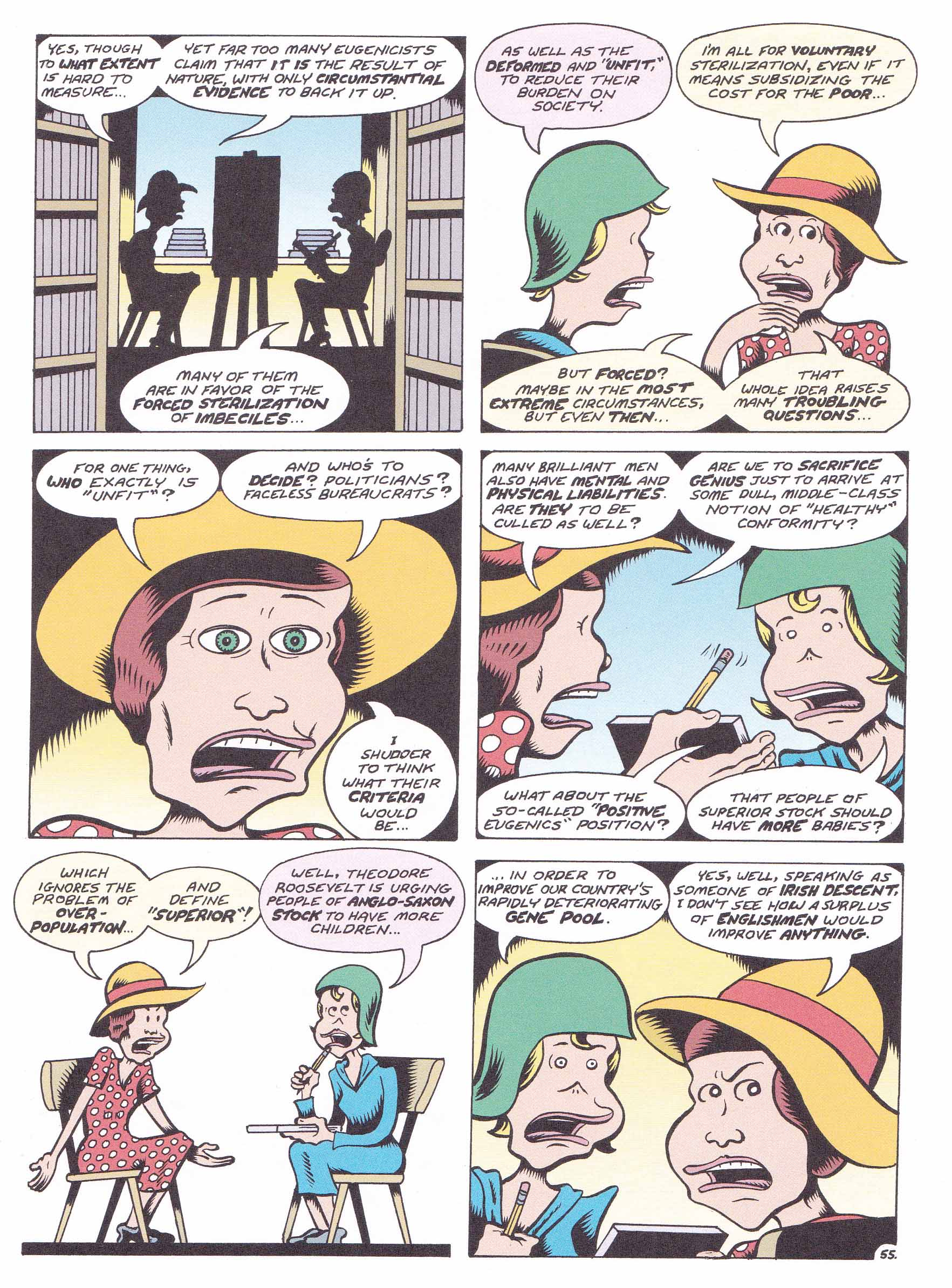

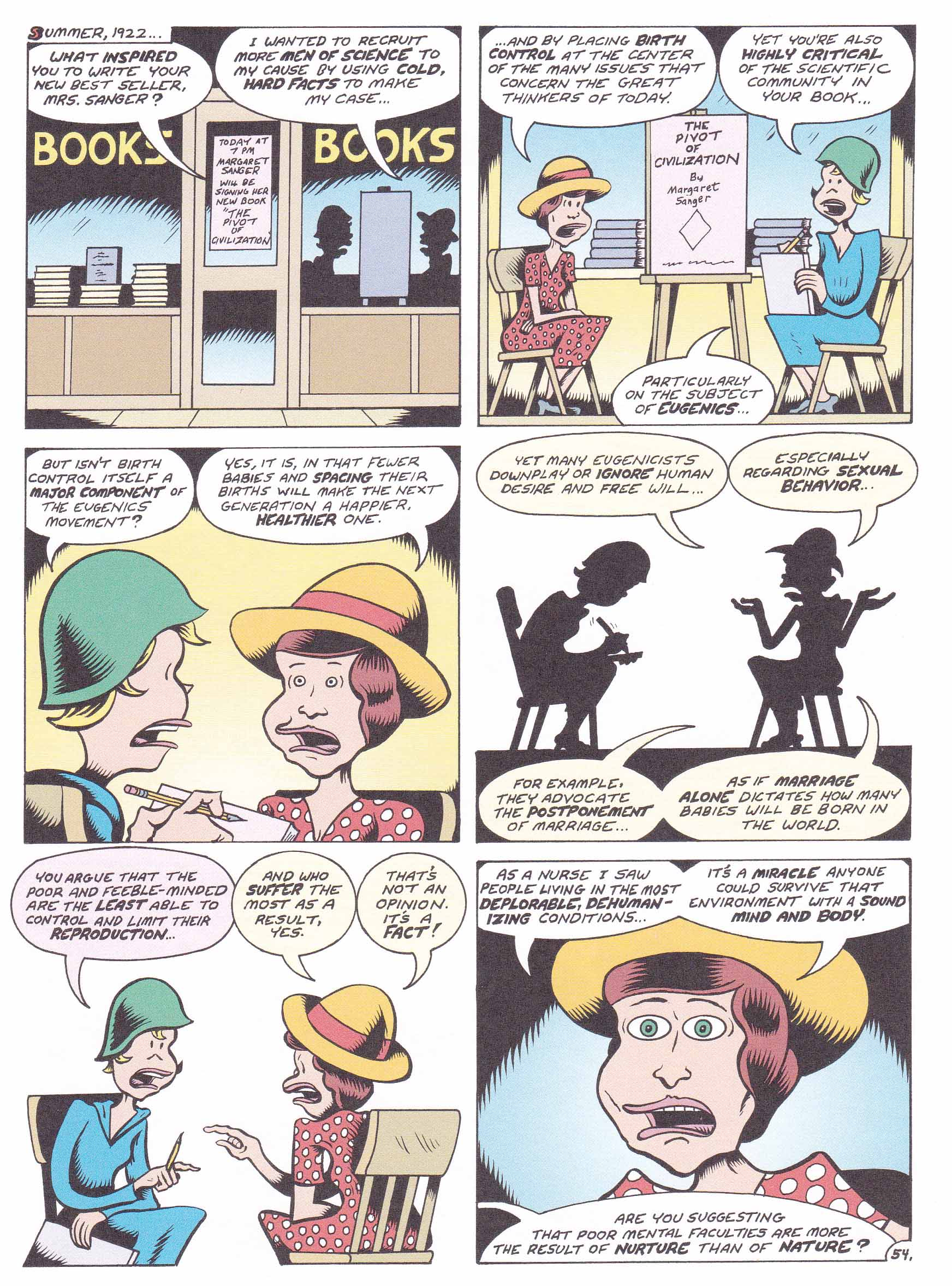

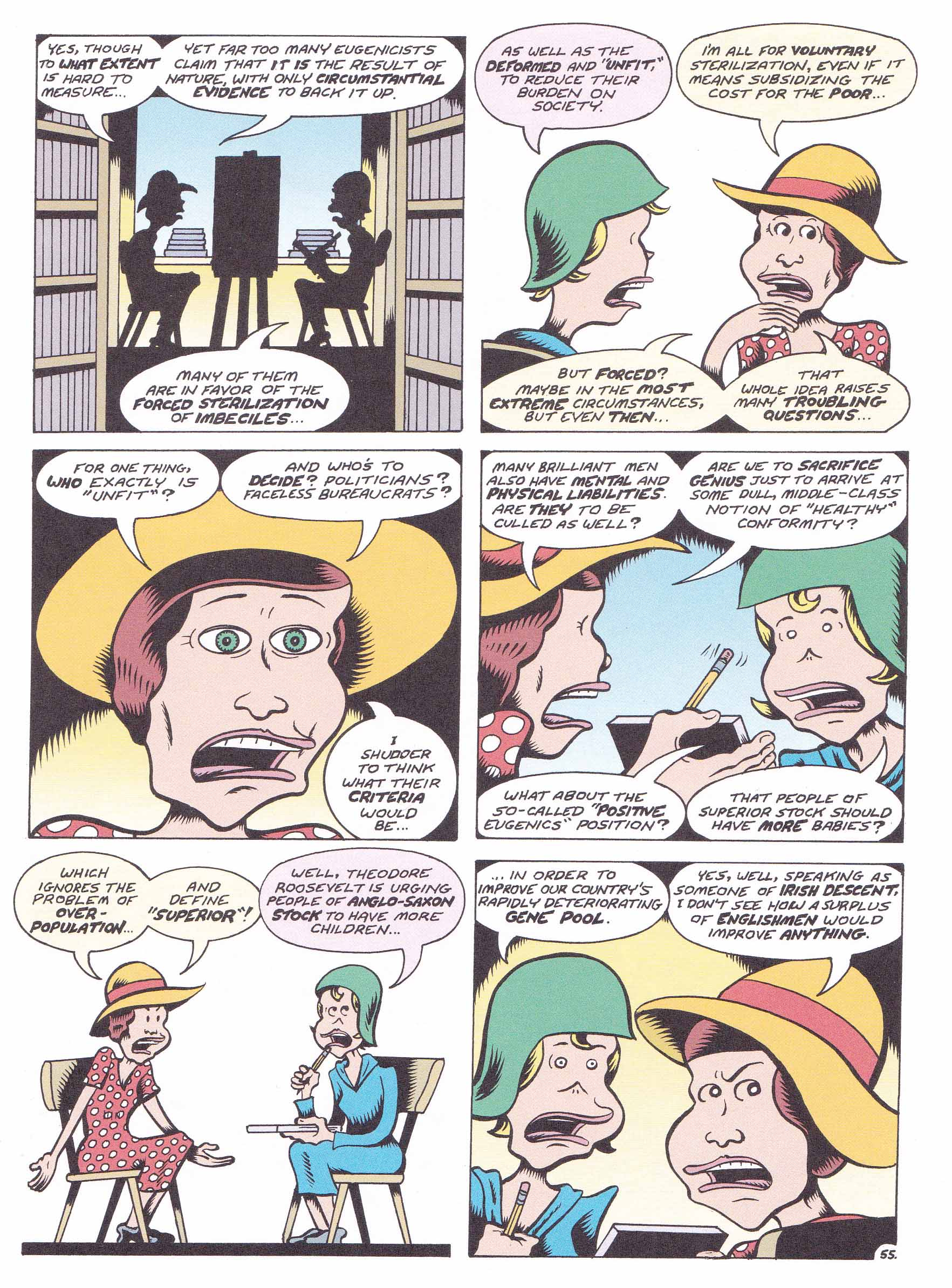

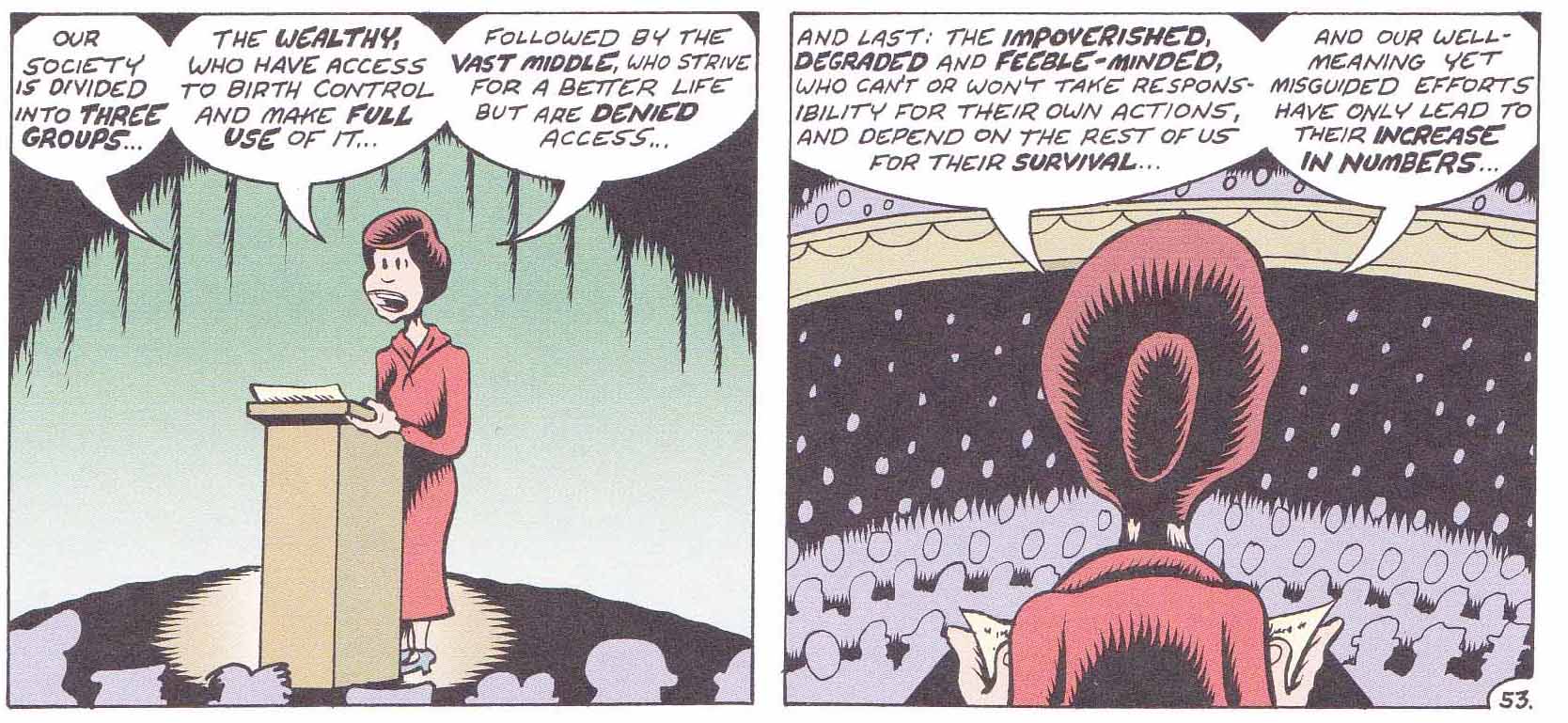

Contrary to what might be gleaned from most reviews of the comic (see below for exceptions), Bagge does actually cover Sanger’s tilt toward eugenics with a relative degree of thoroughness, devoting at least 3 pages to the issue out of a 70 page book (and another 3 refuting her purported racism) .

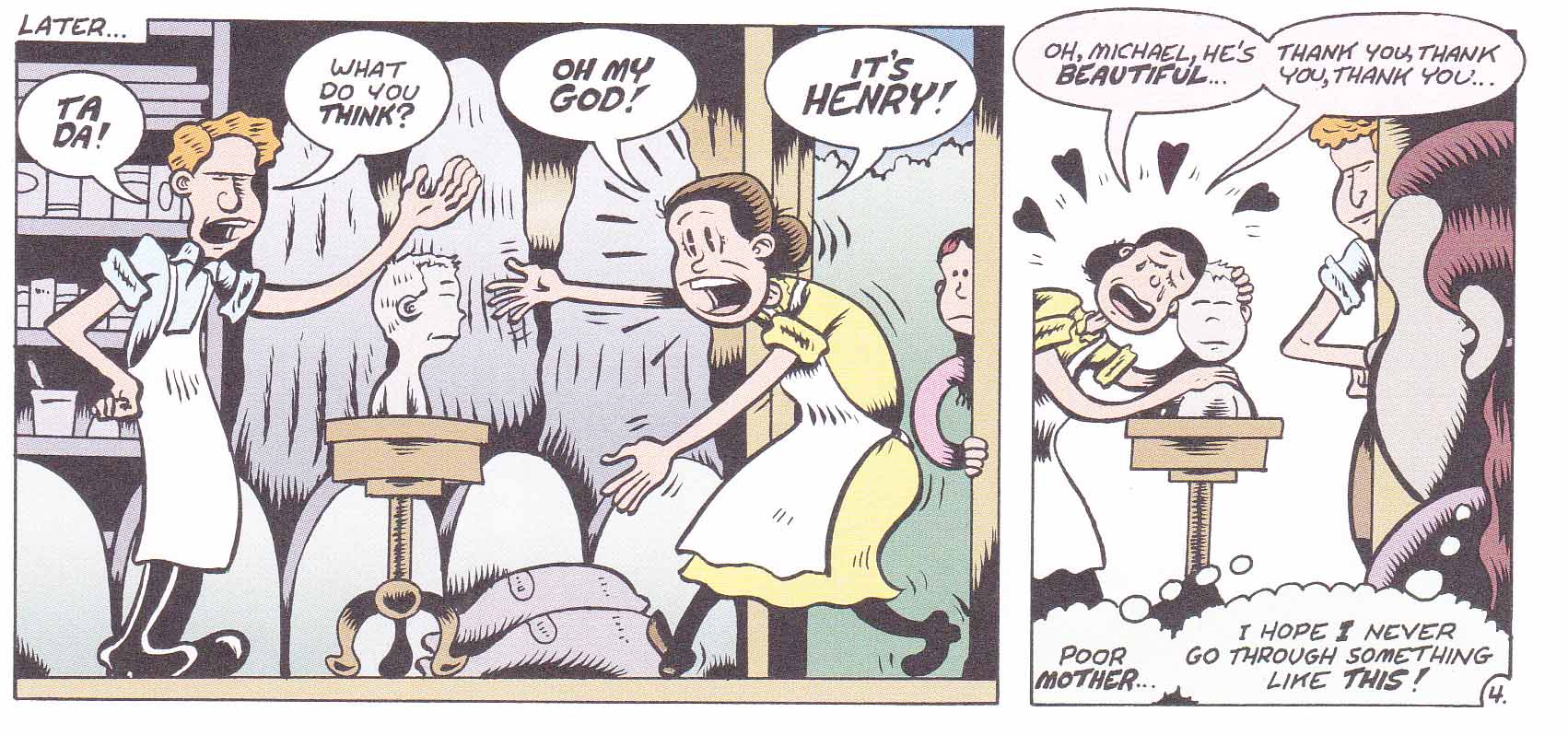

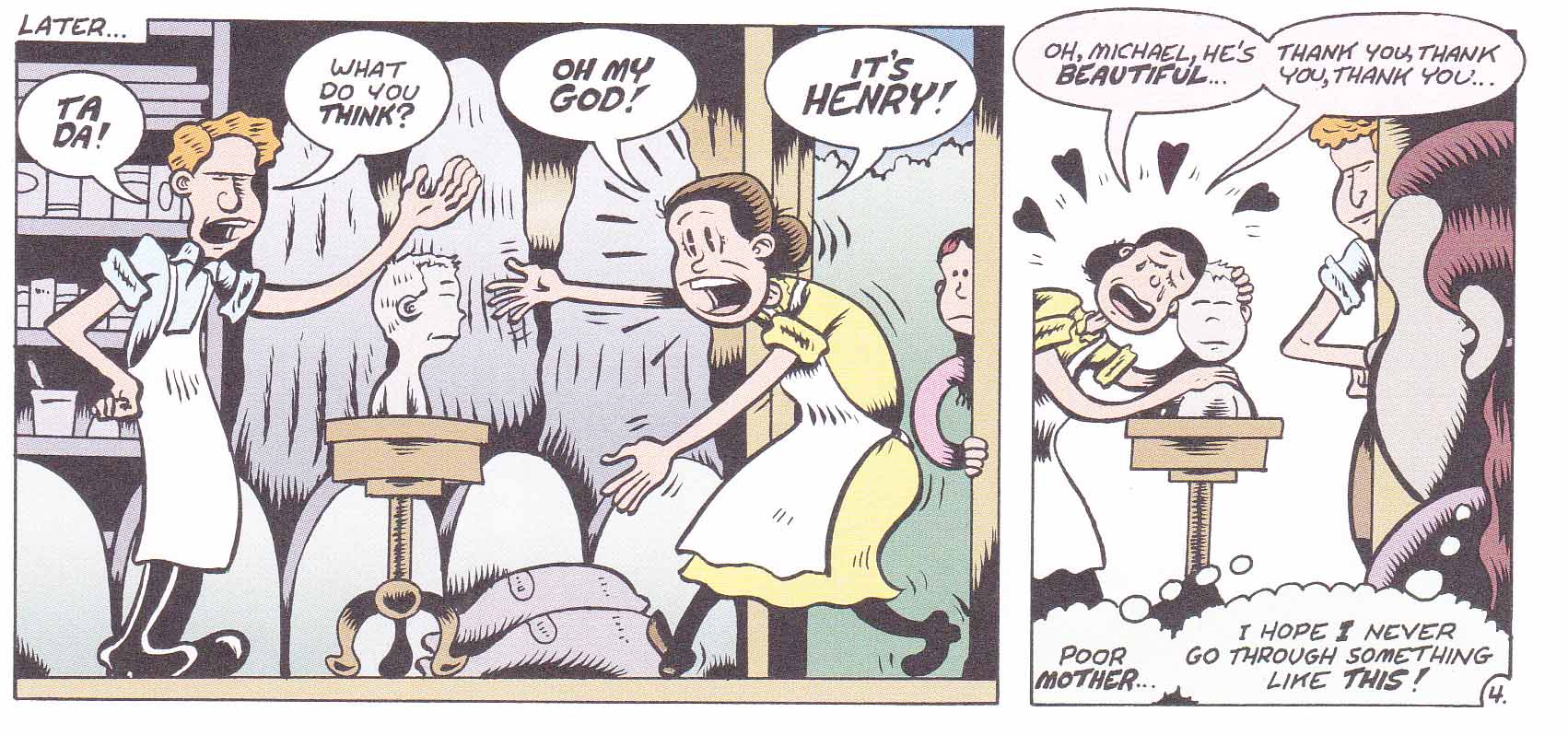

One problem with Bagge’s comic is the style he has cultivated over the years. It is little changed since his days working on Hate, especially the latter issues where he abandoned his more personal busy linework and delegated the inking to a number of hired hands. This works wonders during the two page episode with sexologist, Havelock Ellis, cited in a number of reviews of the comic but it is a distinct hindrance when faced with moments of violence and misery. Take for example the two page sequence where Sanger helps to create a death mask for her deceased brother. One presumes that some of the panels on the page in question are meant to denote stomach churning terror but the reader feels nothing of the sort. The tearful “reunion” of Sanger’s mother with the face of her deceased son should feel crushing in its futility but seems more like a scene from tawdry potboiler. Perhaps that was the intended effect.

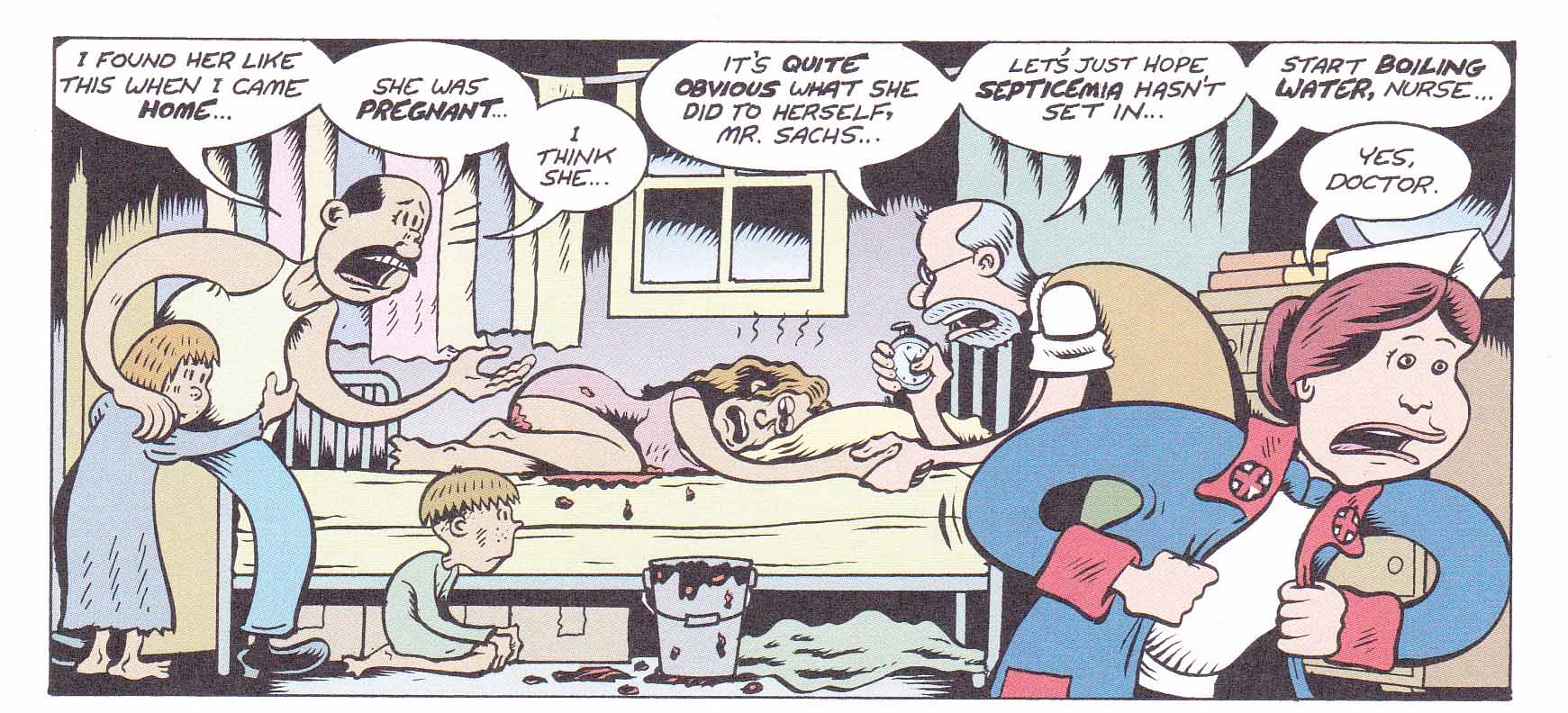

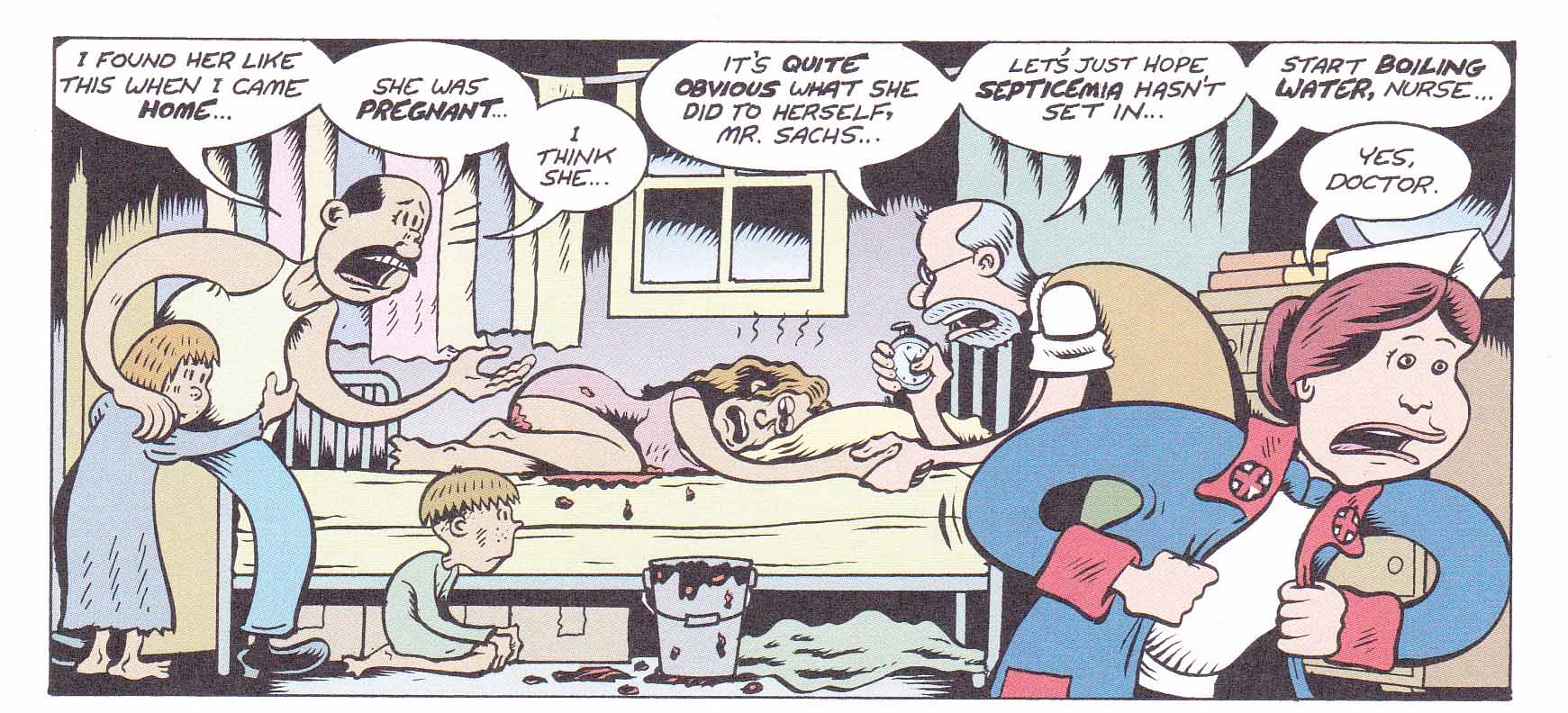

The same may be said for a sequence showing a self-induced abortion which might just as well be a ridiculous portrait of post-alcoholic stupor and diarrhea from an early episode of Hate.

There is a huge emotional chasm created by Bagge’s use of caricature to illustrate these scenes.

This same confluence of big foot cartooning and bright coloring creates a more congenial atmosphere when the serious issue of Sanger’s eugenic inclinations are discussed on pages 53-55 of the book.

Judging from these two pages, I would say that Bagge has done an impressive job padding Sanger’s often ugly ideas with seemingly logical arguments about the difficult but necessary job of social engineering. Who could possibly blame Sanger for her musings when even Theodore Roosevelt (and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. for that matter) were raving eugenicists?

Consider the first panel of the second page where Sanger speaks out in favor of “nurture” (i.e. environment) over “nature” (i.e. heredity). This line of thought emerges from The Pivot of Civilization (Chapter VII) and proves to be considerably more controversial then one would presume from Bagge’s dramatization .

It should be noted that almost everything in Sanger’s book is seen through the lens of birth control (and not “charity”—which is accounted useless). There she writes:

“While it is necessary to point out the importance of ‘heredity’ as a determining factor in human life, it is fatal to elevate it to the position of an absolute. As with environment, the concept of heredity derives its value and its meaning only in so far as it is embodied and made concrete in generations of living organisms….Our problem is not that of ‘Nature vs. Nurture,’ but rather of Nature x Nurture, of heredity multiplied by environment…”

“To the child in the womb, said Samuel Butler, the mother is ‘environment’ She is, of course, likewise ‘heredity’…The great principle of Birth Control offers the means whereby the individual may adapt himself to and even control the forces of environment and heredity.” [emphasis mine]

As for the third panel on the second page where our heroine ponders the question of the “fit” and “unfit”, Sanger was less ambiguous than the stated, “And who’s to decide? Politicians? Faceless Bureaucrats?” Her qualms on this subject had nothing to do with the choice between intelligent individuals and imbecilic ones, but class, gender, and most importantly, the type of genius being cultivated. This too comes from Pivot where she writes:

“…we should here recognize the difficulties presented by the idea of ‘fit’ and ‘unfit.’ Who is to decide this question? The grosser, the more obvious, the undeniably feeble-minded should, indeed, not only be discouraged but prevented from propagating their kind. But among the writings of the representative Eugenists one cannot ignore the distinct middle-class bias that prevails… As that penetrating critic, F. W. Stella Browne, has said…’The Eugenics Education Society has among its numbers many most open-minded and truly progressive individuals but the official policy it has pursued for years has been inspired by class-bias and sex bias….’

“The trouble with any effort of trying to divide humanity into the ‘fit’ and the ‘unfit,’ is that we do not want, as H. G. Wells recently pointed out, to breed for uniformity but for variety. ‘We want statesmen and poets and musicians and philosophers and strong men and delicate men and brave men. The qualities of one would be the weaknesses of the other.’ We want, most of all, genius.”

Here is Bagge in further explanation from his extensive notes on this portion of the book:

(1) BAGGE: “The Pivot of Civilization…Her critics continue to mine it for evidence of her eugenic thought crimes, yet she spends a large portion of the book criticizing what were then established mainstream eugenic beliefs.

While agreeing with many of their most repulsive ideas I should add.

Much of The Pivot of Civilization is actually inoffensive description of the plight of women and children from the lower strata of society with Birth Control being the key to their (and civilization’s) freedom from the plague of overpopulation. For example, she links child labor with “uncontrolled breeding.” You could argue with the (social) science perhaps but not the intent. Where would one put structural inequality in this equation for example?

Sanger, while acknowledging civilization’s indebtedness to the “Marxians for pointing out the injustice of modern industrialism,” was largely dismissive of the Socialistic tendencies of the time. Of the “gospel of Marx” she wrote:

“It is a flattering doctrine, since it teaches the laborer that all the fault is with someone else, that he is the victim of circumstances; and not even a partner in the creation of his own and his child’s misery.”

The real problems begin with the fourth chapter of Pivot titled, “The Fertility of the Feeble-Minded” where she writes in her opening foray:

“Modern conditions of civilization…furnish the most favorable breeding-ground for the mental defective, the moron, the imbecile. ‘We protect the members of a weak strain,’ says [Charles] Davenport, ‘up to the period of reproduction, and then let them free upon the community…so the stupid work goes on of preserving and increasing our socially unfit strain.’”

And soon after:

“Modern studies indicate that insanity, epilepsy, criminality, prostitution, pauperism, and mental defect, are all organically bound up together and that the least intelligent and the thoroughly degenerate classes in every community are the most prolific.”

And to end:

“Every feeble-minded girl or woman of the hereditary type, especially of the moron class, should be segregated during the reproductive period….The male defectives are no less dangerous….Moreover, when we realize that each feeble-minded person is a potential source of an endless progeny of defect, we prefer the policy of immediate sterilization, of making sure that parenthood is absolutely prohibited to the feeble-minded.”

(2) BAGGE: “…Sanger addresses the idea of involuntary sterilization almost as default position, and then proceeds to raise the problems inherent in that idea. But in 1922, that was the default position at least amongst the intellectuals, academics, and progressives that she was trying hard to sway…they were faced with brand new social problems the likes of which humanity had never dealt with before: exploding population growth, rabid urbanization, and massive waves of immigration…All of this lead to increased rates of crime, poverty and mental illness that overwhelmed major US cites. In the face of all this, the idea of sterilizing…seemed like not only a good idea, but the most humane one, considering the options available at the time (another popular solution was to exterminate some or all of the above).

“What Sanger was trying to do was expand our options, so we wouldn’t have to resort to such extreme measures.”

As is clear from Sanger’s The Pivot of Civilization, the first part of Bagge’s statement is complete hogwash. Certainly some would contest the idea that involuntary sterilization was the default position of intellectuals of the time. Quite the contrary, there were some intellectuals who were violently against eugenics itself. Bagge, however, qualifies his statement with the proviso that these were only the intellectuals “she was trying hard to sway.” Since these individuals were largely engaged in the pseudoscience of eugenics, it stands to reason that involuntary sterilization would be popular among them. It is a somewhat circular argument.

(3) BAGGE: “Interestingly, since we now have more scientifically advanced forms of birth control, government agencies imposed temporary forms of forced sterilization on various wards of the state, such as “chemical castration” of paroled sex offenders or Norplant devices for impulsively promiscuous girls in the foster care system. All things considered, these are not unreasonable solutions…”

Of course, these ideas sound all too familiar even in an age when the “science” of eugenics has either gone into hiding or put on new clothes.

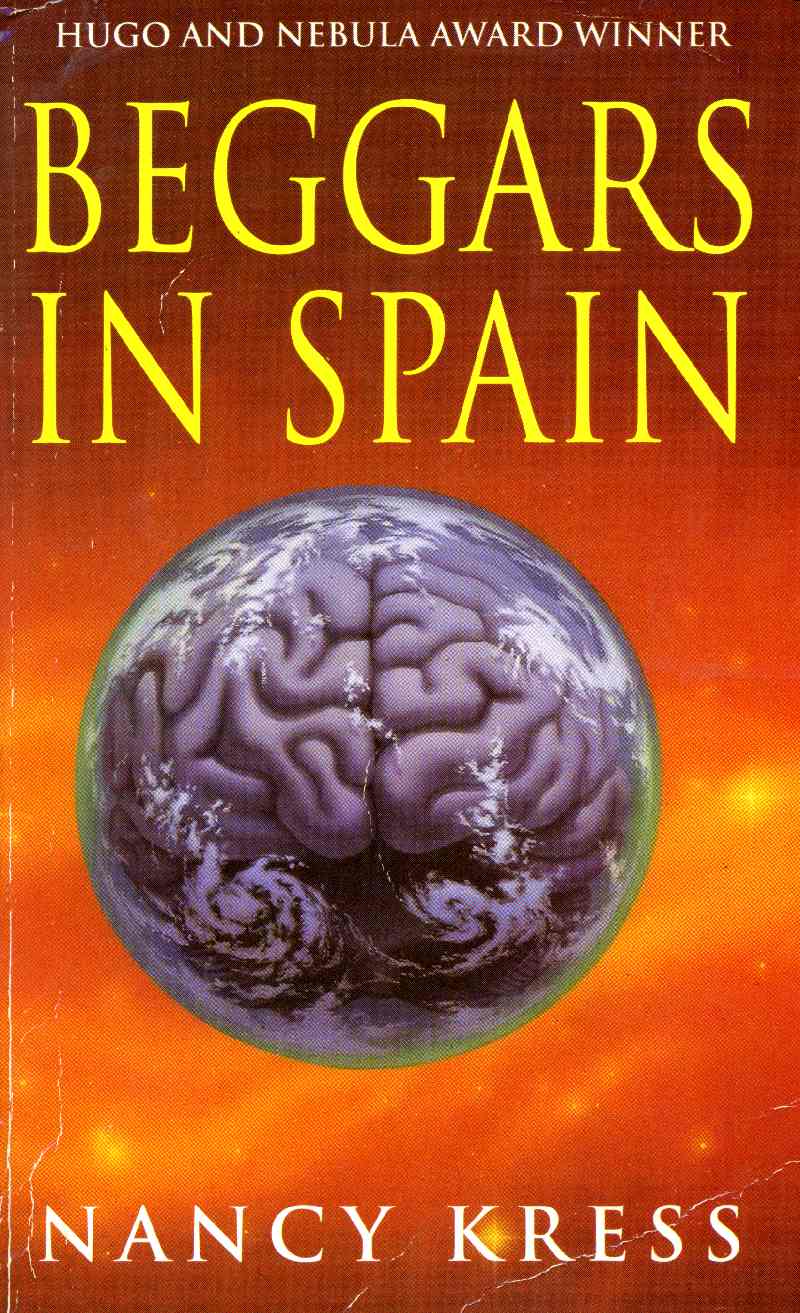

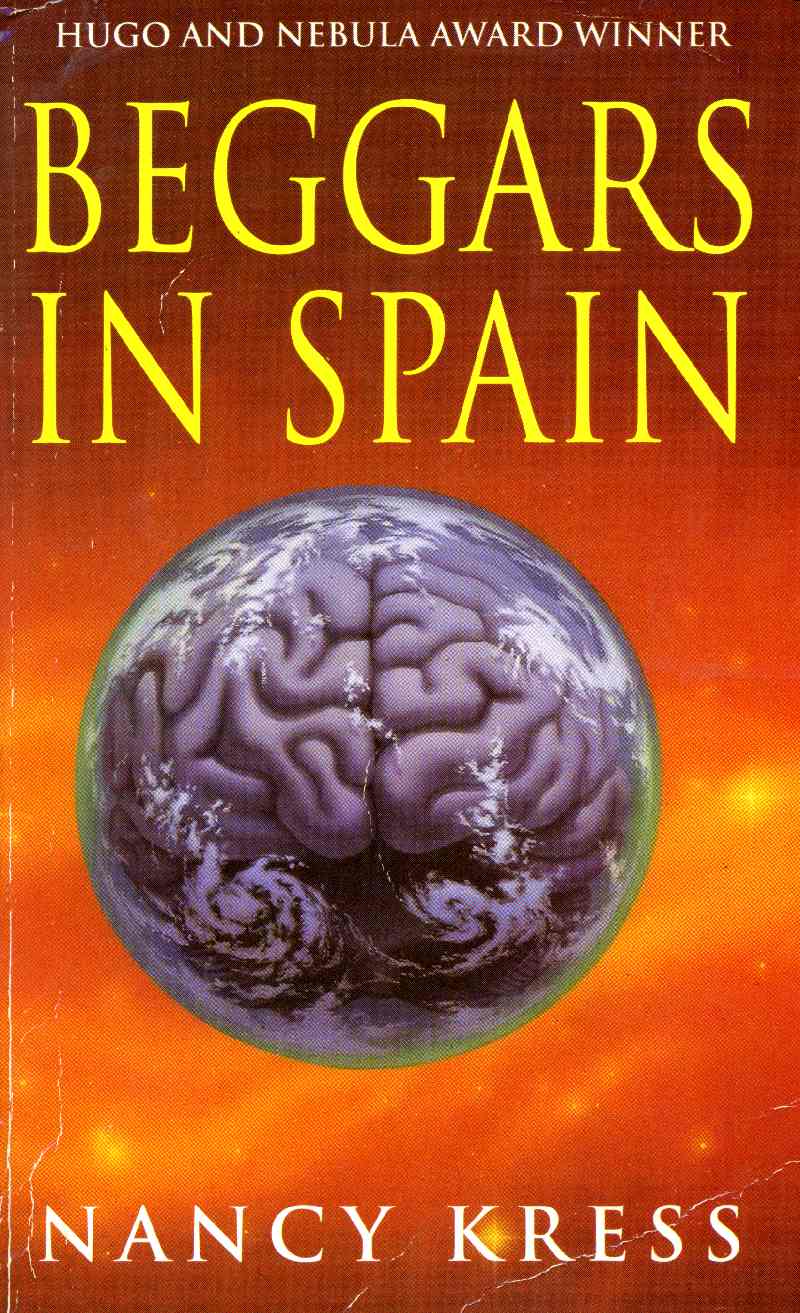

In the realm of popular culture, it is best exemplified by Nancy Kress’ novella (chapter 1 of the later novel) Beggars in Spain. Readers on Amazon.com have accurately labeled Beggars in Spain the “perfect book to read before or after Atlas Shrugged”…because it adds so beautifully to the basic arguments of the Have and the Have-Nots.” The soft-Objectivist SF novel which won it all is seen by some as the authoress’ conversation with the ideas of Ayn Rand and, by others, as a paean to the new Objectivism (specifically its ethics). Of course it doesn’t seem to have been promoted that way but you would only need to read 50 pages into the novel to sense the essence of its intent. I had not read 1/4 of the novella before I realized that what I thought were simple quirks were actually the entire measure of its premise.

Beggars in Spain is not completely adamant in its greed and selfishness but it is pretty certain in its diagnosis of one of the major ills of society: the fear, demonization, victimization of, and parasitic reliance on society’s highest achievers. Like Rand, Kress’ work displays an unabashed admiration for elitism but, unlike some of its esteemed forebears, finds a place in its heart for the moochers of society—the eponymous Beggars in Spain.

The metaphor hinted at in the novella’s title is explained in a parable told to Leisha, the protagonist of the work:

“What if you walk down a street in Spain and a hundred beggars each want a dollar and you say no and they have nothing to trade you but they’re so rotten with anger about what you have that they knock you down and grab it and then beat you out of sheer envy and despair?”

Leisha didn’t answer.

“Are you going to say that’s not a human scenario, Leisha? That it never happens?”

“It happens,” Leisha said evenly. “But not all that often.”

“Bullshit. Read more history. Read more newspapers. But the point is: what do you owe the beggars then? What does a good Yagaiist who believes in mutually beneficial contracts do with people who have nothing to trade and can only take?”

“You’re not–”

“What, Leisha? In the most objective terms you can manage, what do we owe the grasping and nonproductive needy?”

“What I said originally. Kindness. Compassion.”

“Even if they don’t trade it back? Why?”

“Because…” She stopped.

“Why? Why do law-abiding and productive human beings owe anything to those who neither produce very much nor abide by just laws? What philosophical or economic or spiritual justification is there for owing them anything? Be as honest as I know you are.”

Leisha put her head between her knees. The question gaped beneath her, but she didn’t try to evade it. “I don’t know. I just know we do.”

And there’s the compassion tacked on to the old elitism, the now passé form of Objectivism. Nancy Kress explains this more fully in an interview quoted by Nicholas Whyte in his review of Beggars in Spain:

“…although there’s something very appealing about [Ayn Rand’s] emphasis on individual responsibility, that you should not evade reality, you should not evade responsibility, you should not assume that it’s up to the next person to provide you with your life, with what it is that you need, whether that’s emotional, or physical… [it] lacks all compassion, and even more fundamental, it lacks recognition of the fact that we are a social species and that our society does not exist of a group of people only striving for their own ends, which is what she shows, but groups of people co-operating for mutual ends, and this means that you don’t always get what you want and your work does not always benefit you directly.”

Whyte goes on to say that

“…the central message of Beggars in Spain is that our humanity as individuals is bound up in our obligations to the rest of humanity, and if we forget that, we become less human.”

So much for intent, but what do we as readers find in the novella, that long short story which won a bounty of awards and recognition.

The protagonist of the novel is Leisha Camden who has been genetically engineered for sleeplessness. She is genetically perfect both in mind and body. Not so the fountainhead of her being, her mother.

Leisha’s mother, who rejects the protagonist’s genetic genius, is a cold, alcoholic wuss who abandons her daughter because she cannot see herself in that superior specimen of society.

Leisha’s “ordinary” sister is left shivering in the long shadow of her sister’s massive intellect and brilliance. She turns her frustration and anger inward; rejecting a planned admission to Northwestern University by becoming first an unwed mother, then an abused wife, and then, horror of horrors, obese! This before seeing the light, leaving her abusive husband, shedding the pounds, and applying to college. In this way, it is rationalized, the beggars don’t always have to be beggars. If only more “normal” people saw the light and changed their lives for the betterment of society.

Beggars in Spain is undoubtedly one of the most frightening novellas to have won both the Hugo and Nebula award. It can also be read as a metaphorical road map towards a caring Objectivist Utopia. The genetically altered Sleepless not only become more intelligent but also regenerate indefinitely—they are veritable demi-gods. The greatest and most intelligent in society are placid, rational, and calm. Many have almost immaculate personalities. Their intelligence and mental superiority is directly connected to morally upright behavior. It is a Libertarian fever dream where the plebs (lacking this intelligence and moral fiber) feel jealous and seek to deprive these individuals of their rights under the American Constitution.This is not so much a case of “America the Beautiful” but “America the Full of Shit.”

It is worth noting that the American eugenics movement largely thrived on the basis of philanthropy, in particular money from the Carnegie Institution but also funds flowing form finance, oil, and railways. In other words, the very demi-gods hailed in Beggars in Spain, a novella rooted in a preposterous (and certainly ahistorical) conception of human behavior. Many of these organizations have since repudiated their actions.

Peter Bagge is, I think, a Libertarian, or at least he sometimes identifies as one. This does not mean that he holds to any of Objectivism’s (or Rand’s) more distasteful views.

Bagge seems to suggest that the slant he provides in Woman Rebel was a strategic decision made against pro-life groups (from an article at Raw Story):

“Those groups also hype Sanger’s belief in the progressive-era theory of eugenics, which Bagge says has become synonymous with fascism and Nazism.

“During the progressive era, especially in the 1920s, when eugenic thought was at its peak, it was much more wide-ranging that that,” Bagge said. “There weren’t very many people who did believe in it along very specific racial lines.”

He says Sanger accepted the views of eugenics promoters to help promote her ideas about birth control among “men of science.”

“She wouldn’t rule out forced sterilizations in extreme situations,” Bagge said. ’Extreme,’ in her case, how she would define that is, a destitute woman who is, like, extremely mentally incapacitated and neither her or her family have any way of raising a child.”

Bagge’s view are of a piece with those of Ellen Chesler who is quoted by Anna Holley as saying that

“Margaret Sanger had no choice but to engage eugenics. It was a mainstream movement, like public health or the environment today. It was to sanitize birth control and remove it from the taint of immorality and the taint of feminism, which was seen as an individualistic and antisocial group that addressed the needs of women only, and immoral women at that’”

Bagge’s decision is probably understandable considering the fraught situation which still surrounds the issue in America. I, of course, speak from the relative “safety” of Singapore where these rights are secure, and both positive and negative eugenic solutions (see Graduate Mothers Scheme and here) were once advocated at the highest level of government as recently as the 80s. Still, there is little doubt that Bagge’s portrait of Margaret Sanger suffers from an excessive use of concealer.

Edwin Black’s portrayal of Sanger is considerably less sanguine. The line from the American eugenics movement to the Nazis and the Holocaust is crystal clear but Sanger was not involved in this cross fertilization. However, Black does suggest that Sanger’s interest in eugenics rose from a deeper ideological source which she carried into the 50s when eugenics was increasingly discredited (Sanger died in 1966):

“…on May 5, 1953, Sanger reviewed the goals of a new family planning organization – with no change of heart….Sanger asserted to a London eugenic colleague, ‘I appreciate there is a difference of opinion as what a Planned Parenthood Federation should want or aim to do, but I do not see how we could leave out of its aims some of the eugenic principles that are basically sound in constructing a decent civilization.”

Life is more strange and people more complicated than we give them credit for. A more truthful account of Sanger’s legacy would be a much needed admonition against the idolization of any human being no matter how beneficial their actions may appear to have been. If an idea is good and ethical, its practice should not be predicated on the saintliness of the individual(s) who first championed it. That is the preserve of religion. The future described by Kress in Beggars in Spain is now upon us. We now lie on the cusp of “self-directed evolution”. But the progress of science has never been at the heart of the problem. It has been merely an invitation to good or evil; and that choice, that problem has never left us since humans first began to think.

* * *

Further Reading

Hilary Brown at Paste Magazine on the comic.

“He presents the bad — her late-life addiction to painkillers, her difficulties with her children, her fricative relationships with other women of power — as well as the good with an even hand.”

Rachel Cooke at The Guardian on Bagge’s comic.

“Bagge is clearly on Sanger’s side, admiring of her pluck, determination and wildness…he acknowledges that she could be disagreeable, selfish and glory-seeking. This is important, for it was surely her flaws just as much as her virtues that kept her going when the struggle to make birth control legal seemed as though it would never be won.”

Rebecca Henely at Women Write About Comics.

“… he makes pains to defend her against the accusations of racism her memory has been asked to answer for. A notorious incident in which Sanger spoke to a gathering of women in the KKK, her use of outdated and offensive terminology such as “negro” and “imbecile,” and her association with the American eugenics movement have all led to accusations that Sanger’s activism was based on racial supremacy or even as proof that she was part of a conspiracy to wipe out black people, both among conservatives and even those on the left such as Black feminist activist Angela Davis. Bagge, however, argues through the pages of his comic and the afterword that while Sanger was no saint, most of this impression is due to smears that take her words out of context or ignorance of the past.”

A review at Motifri.com.

“Bagge deals with the accusation that Sanger was a eugenicist interested in wiping out non-white races of people by pointing out that Sanger was adamantly against defining one group of people as “superior” to another. Indeed, leaders in the black community sought Sanger out for help, and Martin Luther King was proud to receive an award named in her honor.”