The July 2015 issue of Action Comics (vol.2 #42) has garnered instant praise from critics. In the current storyline, Superman has his secret identity revealed and his powers severely dampened. In a further controversial and news-making development, cops and SWAT teams confront local Superman supporters and engage in a violent attack that prompts the Man of Steel not only to defend the neighborhood from the onslaught of police, but to end the conflict with a right cross to the chief officer’s face.

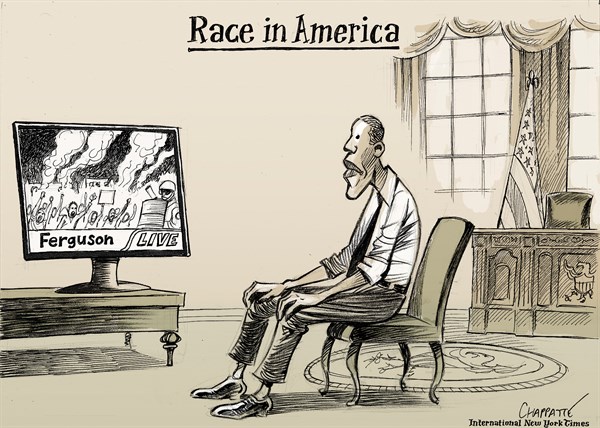

The images of a riot instigated by police naturally conjure up memories of Ferguson Missouri. As a result, the issue has led such online publications as International Business Times and Business Insider to label the story “gripping”, “breathtaking” and “compelling”.

So why is it so lousy?

I’m unsure what’s worse, the lazy storytelling or the mindless praise for it. It’s as though the aforementioned websites happened upon Google images of the issue and quickly churned out a glowing recommendation for the benefit of appearing both pop culture savvy and socially conscious.

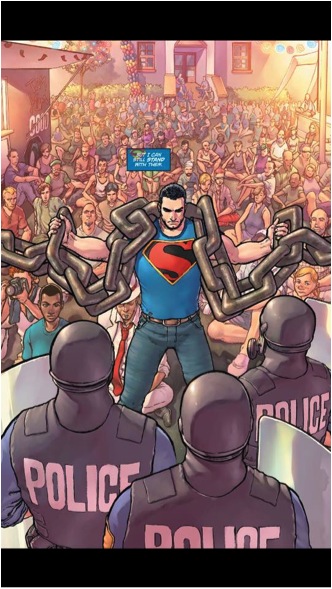

In the sotry, the denizens of the local neighborhood in Metropolis, calling their block “Kentville”, are showing their support of Superman, now publicly known to be Clark Kent. While Superman is away battling a giant monster, a SWAT team arrives to break up the assembly, and within minutes fire an errant canister of tear gas into the crowd. One of the citizens knock it back towards the police, and the neighborhood resigns to sit on the ground and commit to a silent protest, welcoming the oncoming march of the cops who are more than willing to beat everyone to a pulp. Superman arrives with a giant chain held over his shoulders, standing between the SWAT team and the crowd. The lead cop named Binghamton announces that he and the other police will beat everyone on the block including Superman, and then proceeds to do so.

With the Ferguson analogy inelegantly at the forefront, let’s describe how this doesn’t work and what makes its evocation of recent events improper.

1. The SWAT team is brought to disrupt the gathering for Superman without the presence of any sort of protest to disrupt. Unlike in Ferguson, where at the very least tensions had built over an already ever-present sense of racial profiling, the cops are only arriving due to the mustache-twirling machinations of the lead policeman Binghamton.

2. Binghamton’s problem isn’t portrayed as any sort of prejudice or distrust towards Superman because he’s an alien. He openly admits that he’s sick of the praise and adulation Superman has gathered over the years at the expense of the public’s recognition of regular police and firefighters. The conflict isn’t borne out of systemic and long-held prejudices; it’s created by one man’s jealousy of a fictional character.

3. As a result, the conflict between the police and Superman and the protestors is nothing more than a bad guy and his army attacking innocent civilians. It makes the conflict into a too simple case of good vs. evil, removing any semblance of reality. The situation makes the police into supervillains, so that they’re easy to recognize and easy to fight.

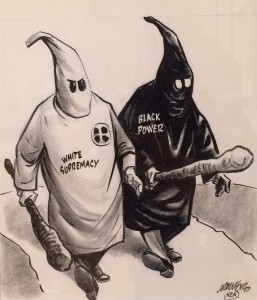

Thus any resemblance to tensions in the real world is removed, and the conflict can go down as easily as any other superbattle. Moreover the way in which the storyline uses the imagery and context of racism is nothing short of appalling.

For one thing, the image of Superman holding a gigantic chain to put himself between the police and the crowd is quite blunt. It’s no doubt supposed to represent shackles of oppression imposed by white authority, but in the hands of a white superhero, it ends up coming across as unearned cultural appropriation. A figure of super-authority such as Superman, powers or no, can’t subsume himself in the community of the subjugated masses when he has traditionally aligned closer to that of a policeman for most of his life. It rings hollow and condescending, as if the story is parodying the resistance to police brutality.

Worst of all is the fact that the overwhelming majority of the people the police are attacking, the ones Superman is defending and the ones that serve to match the Ferguson protestors in this analogy, appear to be white. The firefighter who puts herself at the front of the crowd is recognizably black, but the neighborhood consists of a veritable “who’s who”, or “what’s what” in ethnic diversity. Folks young and old with large noses and middle class clothing make up the whole of the group, with black people ironically the minority of the whole block. This shows that the policemen’s grudge is really no more than a plot necessity that has no bearing in reality. A line by a Hispanic character reads “This is America! This is what I fricking fought for! I’m not gonna let them take that away!” which is answered by the firefighter “If you fight, people are gonna die. Our people. Is that what you want?” This would resonate so much better if both characters were black, not to mention if a majority of the crowd was. As nice as multiculturalism is to see in mainstream comic books, it doesn’t make sense within the context of the story this issue is trying to tell. The police are shown to have such a blasé disdain for the citizens they’re about to brutalize that it makes the story come off as anti-police propaganda more than anything. There’s no nuance, no sense that this could at all take place within the real world.

Superman is supposed to be a Champion of the Oppressed as evidenced by his original Golden Age adventures and later stories as well. He is most effective when battling real world society ills that his readers face every day. So what’s the point in making a story where there’s no actual ill of society or systemic oppression for him to overcome? Was the writer Greg Pak too gun-shy to actually engage in the topic his story’s imagery advertised? The connection between police brutality and racism is not a very difficult concept to grasp, and who better than the world’s first superhero (other than black superheroes) to tackle it head on.

Ultimately the story serves to say “Superman’s one of us!” in a way which doesn’t actually say that. He, like many other costumed heroes, is just like us presuming that we too have a specific and unrealistic villain to face and defeat, rather than the innate problems in our society. As much as people like to lambast the Denny O’Neil/Neal Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow series, that comic at least had the respectability to tackle the problems it saw head on without thinking of misrepresenting it. It named what it saw as what it was and didn’t ignore difficult conversations in a bid for misplaced solidarity. I believe that super hero comics can truthfully engage in contemporary topics—that they can be relevant and contribute to a national conversation. It’s so unfortunate that when it comes to the most pertinent conversation in our nation today, the best superheroes can offer is Action #42.

_______

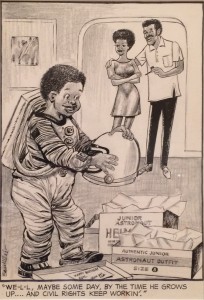

This is part of our ongoing series, Can There Be a Black Superhero?