Over the last few months I’ve been doing an occasional series on the feminist limitations of an ideology of empowerment. My argument has been that a feminism obsessed with power is a feminism that is indistinguishable in crucial respects from patriarchy. It’s also a feminism that tends to reject parts of women’s experiences out of hand. Domesticity, children, family, peace, selflessness, love, and even sisterhood can be tossed by the wayside in the pursuit of an ideally actualized uberwoman valiantly and violently staking vampires or what have you. And as for those who are not ideally actualized — well, for them, empowerment feminism often offers little but contempt and dismissal.

Over the last few months I’ve been doing an occasional series on the feminist limitations of an ideology of empowerment. My argument has been that a feminism obsessed with power is a feminism that is indistinguishable in crucial respects from patriarchy. It’s also a feminism that tends to reject parts of women’s experiences out of hand. Domesticity, children, family, peace, selflessness, love, and even sisterhood can be tossed by the wayside in the pursuit of an ideally actualized uberwoman valiantly and violently staking vampires or what have you. And as for those who are not ideally actualized — well, for them, empowerment feminism often offers little but contempt and dismissal.

I still believe all that. But…well. If anything could convince me otherwise, I think it’s Pedro Almodovar’s “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!”. Mostly because, after watching it, I would like to see a passel of empowered feminists kick the director’s sorry ass.

As I am not the first to notice, “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!” is an intentional, sneering, anti-feminist provocation. Ostensibly, it’s a romantic comedy featuring Antonio Banderas as the adorably amoral ingenue Ricky. Ricky is released from the mental hospital at the film’s beginning, and immediately goes off to kidnap former porn star and drug addict Marina (Victoria Abril). After hitting her in the jaw, he traps her in her apartment and tells her that she is going to fall in love with him and that they’ll then go off and have lots of babies. At first she is incredulous, but then he steals painkillers for her and gets beaten up for his efforts and she realizes that he really does love her…and so she falls for him and they have fantastic sex and then they ride off into the sunset to live happily ever after. Aww.

Like I’ve said, I’ve written a lot in this series about how a feminist text does not have to present women as perfectly empowered, and about how building your life around love is a really reasonable choice. So Marina is not perfectly empowered, and she chooses love. What’s wrong with that?

What’s wrong with that, I’d argue is that I don’t believe Marina is actually choosing love. That’s first of all because I don’t believe in the love. In a good romantic comedy, you need to become a little bit infatuated — or more than a little bit infatuated — with the leads. I don’t necessarily want to marry Cary Grant’s bumbling doofus, but he’s vulnerable and, contradictorily, witty enough that I can see why Katherine Hepburn would. Darcy is almost lovable just on the strength of his having the good sense to fall in love with Elizabeth, but if that weren’t enough, his competence and determination to help not her, but her whole family, certainly seals the deal. Even that bone-headed drama-queen Edward, so desperately trying to be cool and dangerous and so obviously a raging mass of hormones and stupidity trying incompetently to impress and care for the girl he loves — I can see the appeal.

But Ricky? What is there to like about Ricky? I know Edward is supposed to be all stalkery and abusive, but Ricky is actually, literally a stalker and abuser, tracking down a woman he barely knows (they had a one night stand at some point, apparently), hitting her, and threatening to kill her. He constantly engages in petty crimes, shaking down a drug dealer or stealing a car, and while I guess that’s supposed to make him dangerous and cool, in truth it just makes him seem like an untrustworthy thug. Even his tragic backstory (he lost his parents young or some such rot) seems like rote, tedious whining. His bland confidence that he’ll get what he wants; his noxious self-pity (he constantly chastises his kidnap victim for her selfishness and for not seeing how hard things are for him; his vapid cruelty — I mean, I know he’s Antonio Banderas with movie star good looks, but come on. He’s a charmless cad.

Lots of women (and lot of men, for that matter) do in fact date charmless cads — though even the most charmless cad doesn’t generally begin the relationship with battery and kidnapping. But, in any case, I don’t believe Marina is one of those women who dates charmless cads, because, just as I don’t believe in her love, I don’t believe in her. She’s not a real woman — or even a representation of a real woman. She’s got more in common with Pussy Galore than with Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby or Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice or even with Bella. She’s an instrumental fantasy of compliance — which is why her sexual dalliance with a child’s bath toy is what passes for character development. She is there to experience a conversion rape, and the conversion rape is all she is.

Almodovar is perfectly aware of this; in fact, he smirks about it. I mentioned that Marina is a former porn actor. She left porn to star in a exploitation film directed by the great director Maximo Espejo(Franisco Rabal) — roughly translated as “maximum mirror”. Maximo is aging, wheelchair bound, and impotent — he has hired Marina, the film makes explicit (literally in a sequence where Maximo watches one of her old films) because he finds her sexually attractive. The movie doesn’t find this icky, though, Instead, we’re invited to see Maximo’s impotence as a tragedy of genius. His crude comments, directed at both Marina and her sister, are supposed to be cute, just like Ricky’s naive egocentrism and sexual brutality is supposed to be charming. For the last scene of his film, Maximo orders Marian to be tied up and dangled from a window…a motif prefiguring her “relatonship” with Ricky. Ricky, then, becomes, and none too subtly, the director’s avatar, dominating and fucking Marina as Maximo cannot. It’s all just a harmless fantasy, isn’t it? Who are we to deny a genius his stroke material?

Almodovar is gay, of course, so his exact investment in the fantasy is a little unclear. You’re supposed to see him in part as Maximo the mirror, the watcher enjoying or manipulating the tryst. But even if what we have is a coded gay parable about embracing your forbidden love by fucking Antonio Banderas, the fact remains (and is even underlined) that Marina as a woman, and Marina’s desires, are, for the film, utterly irrelevant. It’s not a question of Marina being empowered or disempowered, or even a question of Marina being a blank (as Melinda Beasi recently said of Bella in the Twilight graphic novels.) In fact, it’s not a question at all. The movie simply doesn’t give a crap about Marina. She’s a marker in someone else’s story — which is maybe why she only actually seems to come alive during the film’s much-ballyhooed sex scene. Laughing and animated, she turns over and over with her lover/cad, begging him not to let his penis fall out of her. It’s like Almodovar can only imagine her as interesting, or human, when she’s got a dick.

I did just say in that last paragraph that it’s not about being empowered or disempowered — but I think that’s probably a cop out. The film is, after all, a two-hour paen to the joys of stalking and domestic abuse. It’s a useful reminder to me, perhaps, that one reason men advocate disempowerment for women is that they get off on it. Feminists have every reason to distrust them.

A version of this review first ran on Splice Today.

_____________________

Jim Henson’s televised 70s Muppet Show was an erratic blend of bad puns, pratfalls and surreal, drugged-out humor. An awkward Kris Kirstofferson cracking up onscreen as he sings a love song to a pig; Gilda Radner stumbling through Gilbert and Sullivan tunes accompanied by a seven-foot tall carrot; a giant monster warbling “I’ve got you under my skin” to the civilian he’s just ingested — it was 2nd-rate vaudeville on large amounts of weed performed by shockingly inventive puppets. The Muppet Show never managed the sublime fuddy-duddiness of Peanuts or the anarchically perfect rhythm of Monty Python, or even the occasional brilliant creativity of Sesame Street, but at its best it had a joyously random, unpretentious low-fi charm. I no longer think it’s one of the best television shows of all time the way I did when I was younger, but I still love it.

Which is why the recent film The Muppets made me want to vomit. The clunky sporadic brilliance of yore is gone; in its place is a big, slick, hollow juggernaut, slathered in nostalgia, sentimentality, and a hollow winking irony meant to substitute for humor or ideas. The film puts at the center of the narrative a boy named Walter, who was unaccountably born as a muppet. Out of place in the human world, he provides the pedestrian coming out narrative which has allowed liberal critics to fall all over themselves with enthusiasm. Plus, Walter talks all the time about how great the muppets are and how brilliant the muppet show was and OMG I love the muppets, muppets, muppets. Chris Orr at the Atlantic characterized this as a ” a tidal surge of joyful nostalgia,” but to me it just felt like I was watching a two-hour commercial for the two-hour commercial I was watching. Every gag — Fozzy’s stupid jokes, Gonzo’s “zaniness”, the Swedish chef’s funny accent — is refracted through its own smug self-satisfaction. Which I guess is supposed to distract us from the fact that, for example, Gonzo never actually does anything nearly as wacky as eating a rubber tire to the music of flight of the bumblebee, and Walter, our exciting new muppet, is visually boring as fuck, almost like he was designed by a committee of Disney executives rather than by Jim Henson.

As if Walter’s tedious coming-of-age weren’t sufficient, we also have to suffer through the by-the-numbers bildungsroman of his brother Gary (Jason Segal), who has to learn to commit to his girlfriend of 10 years (Amy Adams.) And of course Kermit and Miss Piggy also must declare their love for one another (as if there was ever any indication in the original show that Kermit liked, much less loved the pig). Even fucking Animal self-actualizes. Everyone learns life lessons and becomes closer together like a family and finds their real place in life, and there are whole scads of big musical dance numbers which are all slickly choreographed and filled with happy lyrics like “Everything is great everything is grand I got the whole wide world in the palm of my hand.” It’s funny, see, because it’s so overly cheerful, just like the original muppet show, and now we’re grown up and know better, but it’s still fun to pretend we think the world is all sweetness and light for the kiddies, right?

The only problem being that the original Muppet Show wasn’t saccharine at all. It was goofy and dumb. It wasn’t about people finding their true place in the world. It was about people falling into holes or transforming their hands into puppies or having random objects fall on them from the ceiling. It was empty-headed, often inventive, sometimes idiosyncratic fun. Period. And now Disney has taken it and transformed it into a paen to finding your own bliss which is utterly indistinguishable from every other wretchedly self-congratulatory paen to finding your own bliss that’s ever defaced a multiplex. Walter’s reverence is supposed to have given new life to his beloved Muppet idols, but instead it’s just buried them in the same old shit.

We’ve been having an interesting discussion over the past week or so about Twilight, the Hunger Games, and the place of empowerment in feminism. Specifically, does a feminist heroine need to be empowered and in control of her own life? Or is the experience of disempowerment — including passivity (or selflessness) and irrationality (or emotional sensitivity) — valuable in itself? Or to put it another way, is feminism’s goal to integrate women into the male world on equal terms, or is it’s goal to change the world in accordance with female experiences?

The 2004 film Ella, Enchanted has an interesting take on these questions. Based on a (better than either Twilight or the Hunger Games) book by Gail Levine, the movie is a reworking of the Cinderella legend. Ella (Anne Hathaway) is as an infant visited by her incompetent fairy godmother Lucinda (Vivica Fox). The godmother gives Ella the gift of obedience.

As Ella’s mother instantly recognizes, and as Ella herself learns as she grows older, the gift is not really a gift, but a curse. Ella has to do everything anyone tells her to do. If her mother tells her to practice her music lessons, she has to practice her music lessons. If she’s told to shovel cake into her mouth, she shovels cake into her mouth. More painfully, after her mother dies and Ella’s evil stepsister discovers her secret, she is forced to perform a series of ever-more-terrible tasks — giving away the broach her mother handed her on her death bed; stealing from a store; and finally, insulting her best friend and telling her she will never see her again.

The film, in other words, is one long treatise about the dangers of disempowerment; the traditionally female virtue of obedience is presented as a kind of fierce and unrelenting slavery. The film, in this sense, is clearly, and strongly, in favor of empowerment — not least in the way in which it takes pains to demonstrate that, while Ella is controlled by her curse, she is not defined by it. Whenever she can, Ella thinks her way around her obedience — when an antagonist tells her “bite me!”, young Ella obliges instantly; older and told to gather bouquets for her stepsisters, she smirkingly collects poison ivy. Moreover, it is not Ella’s obedience, but her feisty independence and her refusal to be charmed by his beauty or rank which attracts the romantic lead, Prince Charmont (Hugh Dancy.)

And yet…is it so clear that Ella is not what she is because of her obedience? The narrator at one point says that Ella’s gift is actually what gave her strength of mind — it is the ordeal of having to obey everyone all the time that made her so determined to think for herself. Even more telling, one of the ways in which Ella has most conspicuously thought for herself is in her political views. She doesn’t like the prince because his uncle’s government has been systematically enslaving other races — ogres, giants, and elves. Ella makes the link quite explicit for the viewer in a discussion with the prince (who is not in on her secret.) After seeing some giants being forced to work in the fields, Ella tells him: “No one should be forced to do anything they don’t want to. Take it from somebody who knows.”

The dichotomy here between obedience-as-a-curse (slavery) and obedience-as-a-gift (source of wisdom and character) can perhaps be traced to the fairy tale source material. As I said, this is a retelling of Cinderella, and a retelling in a feminist vein. The original tale is about a woman being saved by marriage and love; the new tale wants to be a story of an independent woman. At many moments, you can see the fissures. For example, the climactic scene involves a (quite entertainingly silly) battle with a horde of ninja-knights. Prince Charmont battles ferociously — and so, too, does Ella, who has not previously shown any particular capacity for battle (except in one scene where someone ordered her to fight skillfully, that is.) Diagetically, there’s no reason for her to be able to defeat trained warriors; it’s just thrown in to make her look empowered and equal. As such, it comes across (for all its obvious goofiness) as almost condescending. You want empowerment; okay, we don’t really believe in it, but we figure you’re easily satisfied. Here you go.

The tension between Cinderella and Ella is perhaps most apparent, though, at the film’s emotional climax. Prince Charmont’s evil uncle Edgar (Cary Elwes) finds out Ella’s secret and orders her to stab the Prince through the heart at the moment when he asks her to marry him. Despite desperate attempts to escape, Ella has no choice — and as he asks her, she raises the knife. But…a miracle occurs. The strength of her true love releases her from her curse, and she lets the knife drop to the floor as she weeps in relief.

The movie makes some effort to suggest that the breaking of the curse is the result of Ella’s will-power, rather than of true love per se. But…well, come on, now. It’s true love. And even if you insist that it’s true-love-providing-incentive-for-will-power, you’ve still got some explaining to do. After all, as I mentioned, obedience made Ella break off her friendship with her closest friend whom she had known for years. Why wasn’t her love for that friend enough to break the command, while the love for some guy she’d known about a week was? However it’s parsed, heterosexual romantic love, and, indeed, the offer of marriage, is what breaks the spell. Which makes it hard to shake off the sense that the reason Ella is no longer under compulsion to all the world is because she’s under compulsion to one man in particular. And, indeed, Ella at the film’s end is not her own person, but a bride. Her signature achievement is not becoming a lawyer (like her elf friend) or ruling a kingdom (like Charmont. Instead, it’s marrying the king, and influencing him through her love to be a better man and a better ruler.

It would be possible to see these tensions as a sign of the film’s failure to shake off the Cinderella’s stories gushy romance of disempowerment; Ella is more empowered than Cinderella, but she’s not truly empowered.

I think, though, you could also see the ambiguity as a potentially more thoughtful conclusion. When the film goes for empowerment-for-empowerment’s sake in essentially male terms — beating up ninjas — it seems crass and stupid. It’s at its best when it reaches for an empowerment that learns from, rather than entirely rejecting, the Cinderella story. That fairy tale, after all, is about both the injustice of slavery and the beauty of love. Both of those insights, it seems to me, come out of distinctively female experience, and so it makes sense that Ella, Enchanted build its feminism — not perfectly, but still with some conviction and heart — on both.

Gratuitous Harry Clarke illustration, because Harry Clarke is bad ass.

This first ran at Splice Today.

___________________

13 Assassins, directed by Takashi Miike, is a samurai movie dedicated to giving you what you expect in a samurai movie. Disturbing scenes of hari kari? Check. Old sparring partners reunited on opposite sides of an apocalyptic showdown? Check. Intense discussions of honor, honor, and also honor? Yes. Final endless battle scene between a very few and a whole bunch? Of course!

In addition, the film also has a truly dastardly villain: Lord Naritsugu Matsudaira (Gorô Inagaki). Naritsugu is brother to the shogun, and he uses his high standing to be extraordinarily unpleasant. How unpleasant you say? Well, of course, he rapes defenseless women. And then kills their husbands. While staying as a guest in the home of the guy’s father!

For most purposes, that would establish Naritsugu as a villainous villain and worth getting rid of. But! This movie is not sure that you are convinced, so it has him cut off a woman’s limbs and her tongue and then use her as a sex slave… and even that’s not enough. As a bonus, we get to watch him tie children up and make them watch their parents die before he shoots arrows into them.

The idea here, presumably, is to make Naritsugu’s crimes so heinous that eliminating him justifies virtually any amount of carnage. And diagetically, it works—cutting off an innocent girl’s legs and arms and tongue is pretty impressively vile even in the jaundiced post-Saw filmoverse. I was convinced that Naritsugu was a really bad guy, and that letting him get anywhere near the throne was a bad idea. If the shogun won’t act against his brother, somebody in authority should commission as many assassins as possible (sure, 13, if that’s all that’s available) to bring the bastard down. So good for the writers. They have achieved buy in.

Still, as the film rolled along towards its inevitable giant pile of stinking corpses, I couldn’t help but notice some… uncomfortable facts about our arch-nemesis. Specifically, Naritsugu isn’t a standard issue power-mad, scheming kind of villain. He doesn’t need to scheme for power, after all; he just needs to sit around and wait to inherit. He’s not Machiavellian. He just, as one character mentions, has a taste for “flesh.” He’s a dissipated sadist. He likes to hurt people because it gives him sensual pleasure.

As the film moves along, Naritsugu’s decadent sadist starts to drive the plot. Of course, as I’ve already noted, his evil nastiness sets the plot in motion in the first place. But at a couple of points he stops being merely the instigator of the carnage, and starts to actively push it along. His chief bodyguard, Hanbei Kitou (Masachika Ichimura), for example, urges Naritsugu to take the threat from the 13 assassins more seriously. But Naritsugu is having none of it… in part for reasons of honor, but mostly just because he thinks it would be fun to have a big battle. Do the “foolish” thing, he urges Hanbei, who looks as if he’s just been asked to swallow his elaborate hat.

Even in the final battle, Naritsugu behaves less like a man in danger and more like a man… well, like a man watching a movie. As his soldiers die around him, he declares the spectacle “magnificent”—which there’s no doubt it is, visually—and muses on how wonderful the days of war must have been before the shogun established the peace. He tells Hanbei, with an air of dreamy enthusiasm, that when he’s on the shogun’s council he’ll bring those days back. And when the fight is over and he finally realizes things may not turn out all that well, Naritsugu is still enthusiastic about the spectacle. “Of all the days of my life,” he declares to his conqueror as he bloodily expires, “this has been the most exciting.”

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that Naritsugu is more than just the villain of the piece. He’s also the audience surrogate. Like the audience, Naritsugu is deliciously entertained by blood, sadism, and death. Like the audience, Naritsugu anticipates and yearns for the apocalyptic final battle. Like the audience, he is swept away by the glorious reconstruction of the days of war. And, like them, he would like to see those days reenacted again and again.

Perhaps most importantly, Naritsugu is like the audience in enjoying the pageantry of honor while being utterly without honor himself. He is happy to deal death, but faced with death himself he screams and whines—which I presume is what most of my fellow audience members and I would do in his place.

I doubt Takashi Miike necessarily intended Naritsugu to be a portrait of his public—or of himself for that matter. It seems like it’s just an unavoidable structural serendipity. The audience of a war film wants to see war, and is, indeed, the reason the war is being staged. That aligns the viewers with the bad guys; the ones causing the trouble. It’s for our amusement that people get their limbs hacked off and the noble die terrible (but honorable!) deaths. All in make believe, of course. We’re not really as bad as Naritsugu. If we could bring back the age of war, we wouldn’t. Which is why, naturally, we are not fighting any wars at the moment.

I’m pretty sure I saw this a while back when I was obsessed with John Carpenter films, but somehow I never wrote about it. I can see why; while it’s an enjoyable and neatly-plotted film, it doesn’t exactly require complex exegesis. Evil forces of chaos in the person of a (carefully mixed race) LA gang converges on a soon-to-be-decommissioned police station. Good forces of order (with an equally mixed racial profile) resist. Good takes some losses, but ultimately wins. Yay!

Of course, you always know good is going to win in these sorts of films. What’s interesting, maybe, is how little affect goes along with it. It’s possible I’m just jaded, but the sides were drawn so broadly, and the characters were in general so flat, that it was difficult to really feel especially exercised one way or the other about their survival or lack thereof. Ethan Bishop (Austin Stoker) is okay as the inexperienced lieutenant in charge — the actor has some charm, but the writers seem somewhat paralyzed by the film’s audacity in choosing a black man for the role. As a result, the romantic heat gets apportioned out to Napolean Wilson (Darwin Johnston), a dangerous killer turned ally, whose ingratiating bad boy swagger works for about twenty minutes less than the film’s run time. I knew these characters weren’t going to get killed, but if they had I wouldn’t exactly have mourned.

For that matter, the emotional motivator of the film, the senseless shooting of a little girl played by Kim Richards, rather spectacularly fails to emote. Richards, who played Disney roles, trots out every ounce of grating cuteness she can muster, and the actor who plays her dad turns in an Oscar-worthy performance when he merely looks mildly pained rather than actually rolling down the car window and retching noisily. When the kid finally gets shot, my reaction wasn’t stark horror so much as relief that somebody had finally shut her up and I wouldn’t have to hear her whining for ice cream anymore. If civilization demands the defense of this sort of egregious mugging, I think I’m on the side of the faceless Mongol hordes.

If the theme is staid and the plot is predictable and most of the characters are still-born, what’s to like? Well, I like the the way shabby bureaucrat Starker (Charles Cyphers) walks, one shoulder tilted up, so his clothes stick up like he’s wearing a cardboard cutout of a suit rather than the real thing. I like the way one of the gang members looks around the table at his fellows slitting their arms to make a blood pact, turns to his own arm, and slaps it with grim decision to make the vein pop up, as if he’s the world’s most farcically determined Red Cross donor. I liked the ice cream man looking nervously in his mirror at the car driving back and forth, back and forth, and the abrupt irritation with which he turns off his music when he tells that damn girl that the truck is off duty. And I liked just about everything Laurie Zimmer does as the unflappable police secretary Leigh, from the way she barely blinks when she gets shot in the arm to how she languidly sticks a cigarette in Napolean’s mouth to the way she lights the match in a single intense motion. Watching her performance, it’s hard to believe Zimmer never became a star; she’s simultaneously bad ass, vulnerable, and sexy as hell. Sigourney Weaver and Linda Hamilton have nothing on her.

So if the film’s virtues are predicated on its individual moments, does the ideological baggage (good! evil! civilization!) just get in the way? That’s Manny Farber’s termite art point, perhaps — that it’s the small instants of beauty that matter, not the lumbering, gross stabs at significance.

But would those small moments exist without the ideology. It’s the film’s rote latness, the starkness and even clumsiness of the civilization-vs.-chaos schematic, that makes Leigh’s match-strike and all its controlled lust echo with iconic urgency and pleasure. It’s the figuring of the gang as feral beasts which makes that guy striking his arm so hyberbolically sublime. It’s not so much that the moments add up to the ideology as that the ideology makes the moments enjoyable. The meaning is there so you can appreciate the form; the signified points to the sign. If something’s behind you in Plato’s cave, it’s there to add a little shiver between your shoulder blades when Leigh lights that match and the shadows jump out, sexy-cool, against the wall.

A review of Tatsumi. Directed by Eric Khoo. In Japanese with English subtitles. Released 17 May 2011. Un Certain Regard 2011 Cannes Film Festival. [Comics reproduced in article read from right to left.]

Tatsumi (a cartoon adaptation of the manga of Yoshihiro Tatsumi) could be described as something of an anomaly — a project originating from Singapore which was made on the tiny island of Batam, Indonesia; a project no Japanese animation studio would have taken up if only because of its subject matter: slow, serious, immodest, and unsafe for children. The project’s unlikely instigator is one of Singapore’s most prominent directors, Eric Khoo, whose eighth feature this is.

Tatsumi represents Khoo’s first foray into animation. He dabbled in cartooning in his younger days, and those early works often reflect the urban angst and alienation found in many of his movies. As with Adrian Tomine (editor of the new Tatsumi translations published by Drawn & Quarterly), Khoo developed a passion for the gekiga of Tatsumi through the 1988 Catalan edition of Good-Bye and Other Stories. The motivation behind this project would appear to be simple. When asked about the impact of A Drifting Life (Tatsumi’s autobiographical manga) on him, Khoo had this to say:

“I could not stop thinking about it after reading it for three days and that’s when I decided I had to make a tribute film for Tatsumi.”

At 98 minutes, this is a bare bones version of A Drifting Life, charting in short and somewhat cumbersomely narrated sections his beginnings as a young artist, his meeting with Osamu Tezuka, his family travails, and the birth of gekiga. The film is remarkably faithful to the source text with Tatsumi’s comics panels providing the key animation frames and serving as a near rigid storyboard. Interspersed with the snippets of autobiography are adaptations of at least five works from the author’s 70s oeuvre, namely “Hell”, “Just a Man”, “Occupied”, “Beloved Monkey”, and “Good-bye”. These stories can be found in the collections Abandon the Old in Tokyo and Goody-bye, and are derived from the best period of Tatsumi’s work. There are also short sequences from Tatsumi’s pulp comic, Black Blizzard, highlighting and fetishizng its trashy roots by means of a faux four color process not dissimilar to the effect found on the cover of the Drawn & Quarterly edition of the same manga.

Despite Khoo’s personal affection for A Drifting Life, the fragments in the film derived from that novel are undoubtedly the weakest sections, serving largely as somewhat forgettable links to the five main manga adaptations found therein. Even cut down to its basics these segments will try the patience of viewers with any familiarity with the source material. The segment on Tatsumi’s meeting with Tezuka are the most coherent, the rest is inconsequential filler with little emotional drive. Worst of all is the clumsy and melodramatic episode depicting the destruction of the young Tatsumi’s art by his ailing brother.

The real aesthetic failure of Khoo’s film occurs in the differentiation between the autobiographical scenes and the fictional story elements. This blurring of lines may in fact be intentional — a reflection of the largely unvarying style Tatsumi uses for all his projects and also a subtle suggestion that Tatsumi’s violent themes emerged from his own torn psyche. The autobiographical sections are done in a kind of animation short hand (undoubtedly the product both of intention as well as budgetary constraints) and are shown in color for the most part. The fiction adaptations are done in raw black and white, and are more purposefully two dimensional to indicate the source material. Blurred elements intrude into the frame to mimic a camera lens’ shallow depth of field, and the figures are designed and drawn in a vigorous scrawl typical of Tatsumi’s pre-70s comics. They have none of the refinement of Tatsumi’s ink work found in stories such as “Sky Burial” and “Abandon the Old in Tokyo”. The light and breezy tone of A Drifting Life barely registers, and the segments covering it remain resolutely stiff and leaden, no different from the pre-70s strips they unwittingly mimic. The overall effect is not unlike a slightly evolved motion comic. The lack of aesthetic separation between the two narrative strands leads to a certain monotony; life and art inseparable yet flat in affect.

Sound is the one enhancing element in Khoo’s film. While the dubbing of the American soldier in “Good-bye” is calamitous (imagine John Wayne in a sex scene), the panting and gasping of coitus is wisely heightened to a pornographic hyper-reality which is totally in keeping with Tatsumi’s narrative ethos. Where Tatsumi shows us no more than one page of incestuous licentiousness, Khoo’s version is a loud, drawn out fucking.

It surpasses its source material because of its perverse animalism and utter lack of subtlety. The central hook of incest in “Good-bye” might have been sufficient in Tatsumi’s era but no longer. Producing an adaptation some 40 years later, Khoo periodic attempts to intensify the audience’s disgust and revulsion is largely a successful one.

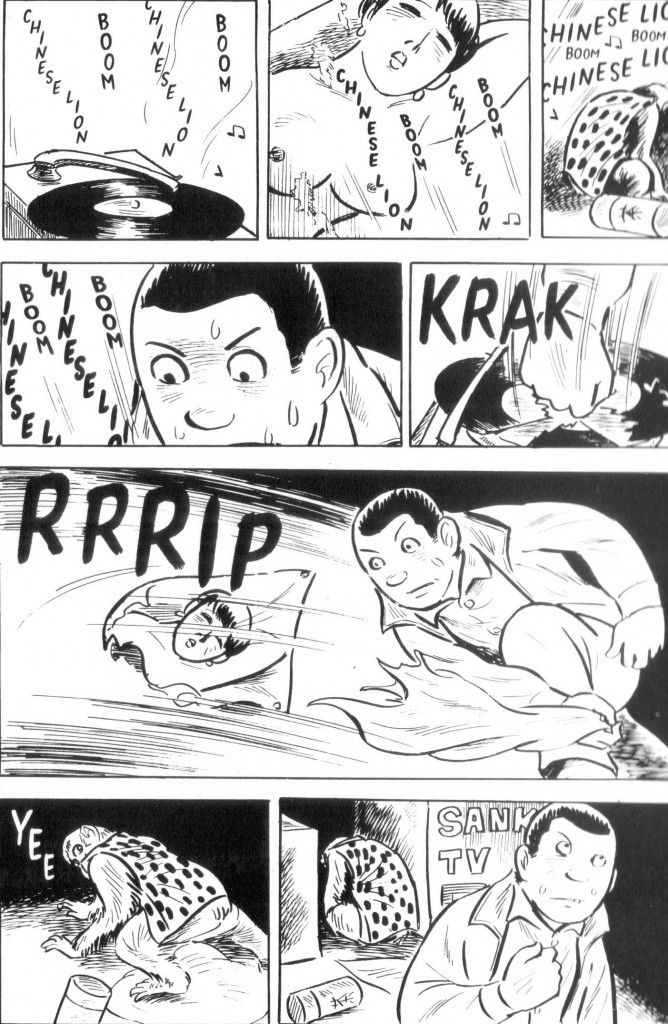

This isn’t the only time that the film adaptation highlights minor weaknesses in the original. The words streaming across the panels in an apartment scene in “Beloved Monkey” (see below) fall short of the more effective and annoying repetition of a stuck record player in Khoo’s movie.

__

__

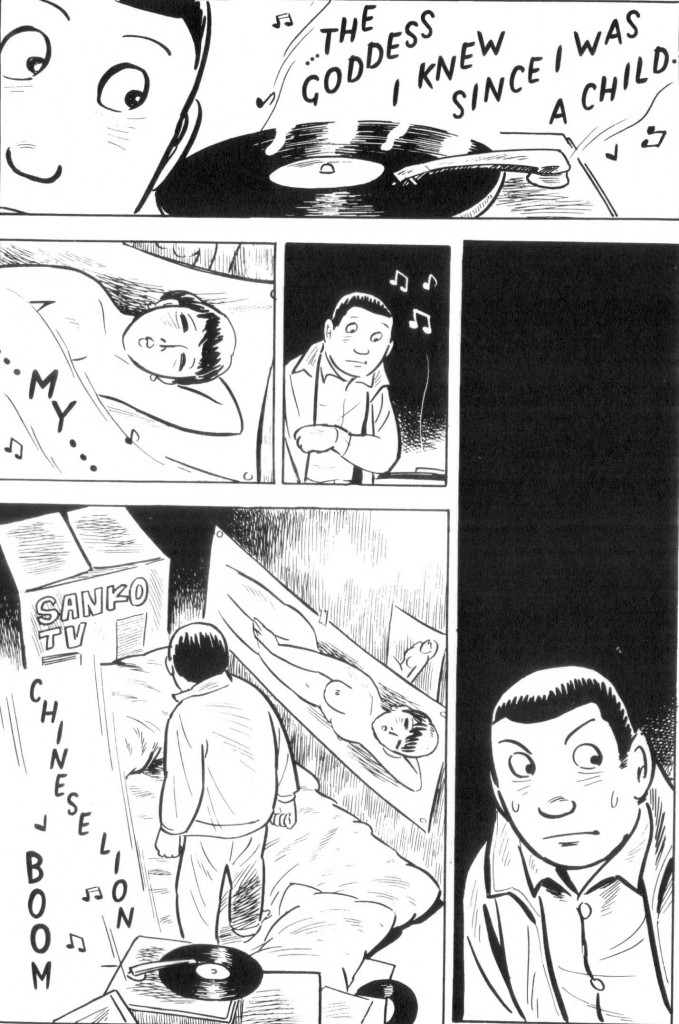

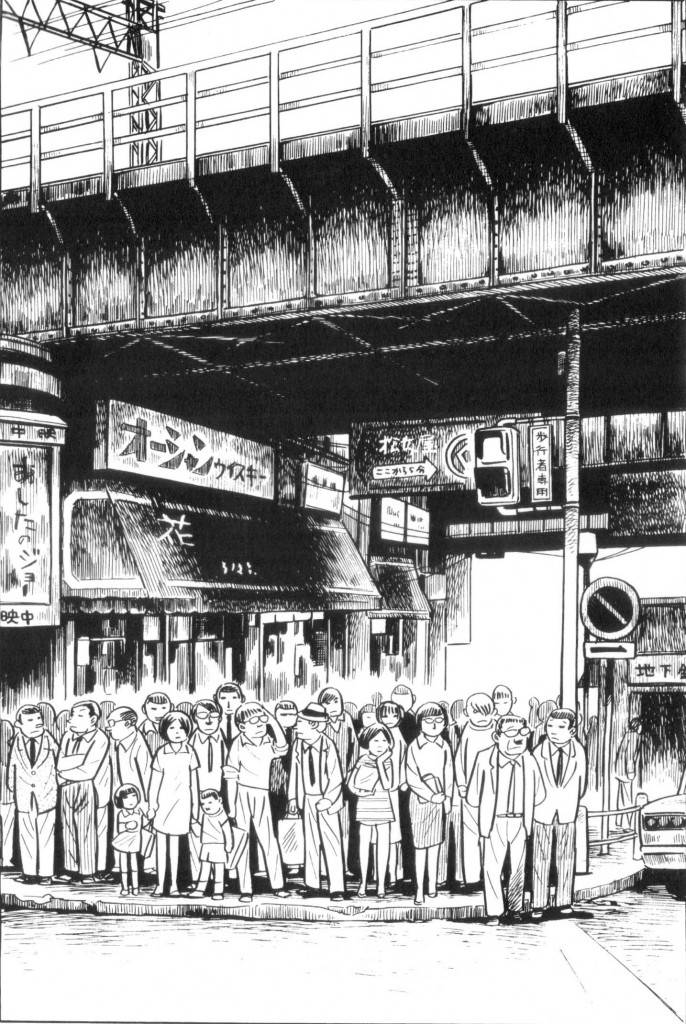

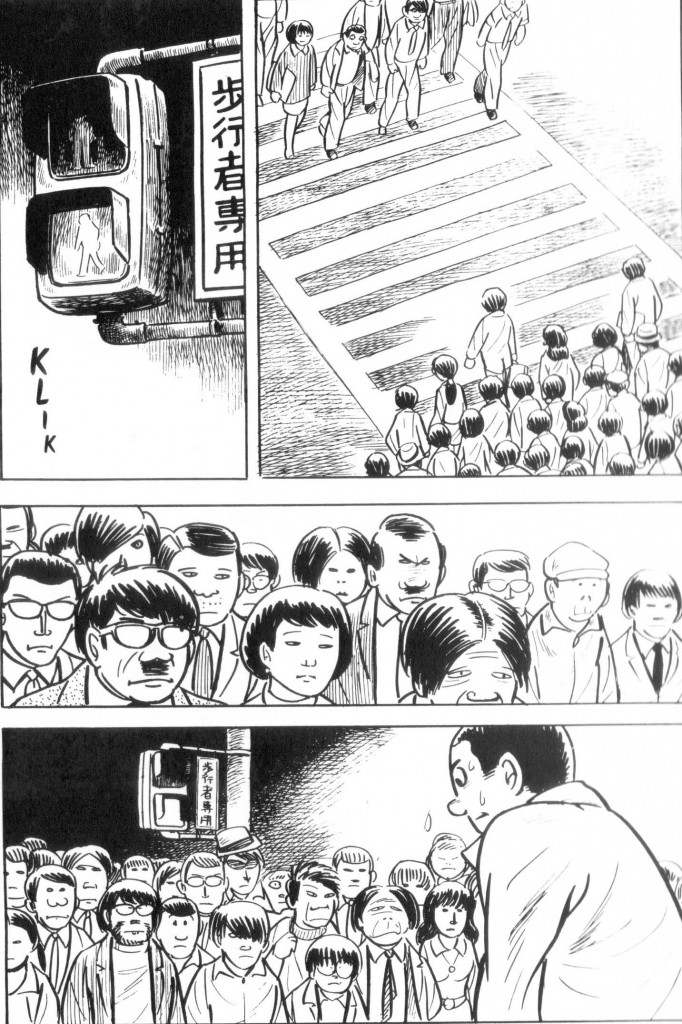

Similarly, the crowd in the final moments of the same story is considerably more threatening — closer, less accommodating, and more menacing — in the film version .

__

__

This may be a case of creative licence. The placidity of Tatsumi’s pedestrians suggest an over-reaction on the protagonist’s part, a festering agoraphobia. Khoo’s adaptation assures us of the validity of this fear. Whether these divergences simply reflect the relative strength and weaknesses of the respective mediums is a subject for another day.

The decision to animate the pornographic graffiti in “Occupied” also yields good results; coarsening the almost asexual nature of Tatsumi’s depictions of female nuditity.

Yet Khoo oversteps the material near the end of his adaptation, introducing a cacophony of siren sounds where none exist in the manga; dampening the faint ambiguity of the manga’s conclusion. It is never clear from the manga whether the protagonist of “Occupied” is apprehended by the police. The film makes certain of this by adding the sound of handcuffs.

The subjective lengthening of the material which works so effectively for the scenes of lasciviousness has its occasional drawbacks. For instance, the opening scenes of a bombed out Hiroshima in “Hell” which are tediously drawn out and which quickly outstay their welcome. Every scene Khoo includes in his adaptation may be found in the original comic, and those 3 pages of ineffectual drawing are faithfully refashioned into a ham-fisted opening sequence only likely to impress the naive and uninitiated.

One might say that the weaknesses in Tatsumi’s stories are brought to vivid life in Khoo’s animation. The manner in which the secretary (Okawa) propositions her elderly boss towards the close of “Just A Man” drew giggles of disbelief from the audience on the night of my screening. In contrast, the panel work in Tatsumi’s manga simply slips past the reader in a matter of seconds causing little if any consternation.

More damaging than all of this is the frigid depiction of creativity; devoid of any sense of the artist’s passion except through the histrionics of the young Tatsumi (in the animation) and the personal claims of the narrator. The final act — that final moment of artistic revelation — where Tatsumi creates a drawing of his old neighborhood falls flat on its face due to the consummate mediocrity of the final product.

Still, the sheer faithfulness of Khoo’s adaptation makes it a perfect tool for publicity, particularly in reference to those who still see comics and animation as the province of children. As Khoo suggests in his interview at Indie Movies Online:

“Because I’m such a fanboy, I hope that people will see Tatsumi and realise “Hey, there’s something to these stories,” and maybe go and buy A Drifting Life, and read 800 pages-worth of his life.”

This is a perfect encapsulation of the film’s worth — a paean to a cartooning deity, a devoted act of promotion, and middling entertainment for the most discerning.

_______________________________________

Related Material

A substantive interview with Eric Khoo at Indie Movies Online

EK: What I told everyone is that, “We will use all his panels as the storyboard of the film.” We do not create any additional shots. Everything must be from the source. And what that meant was that some of the stories I had to edit. The hardest was his life. 800 pages! I had to condense it down to 35 minutes!