I was playing Final Fantasy XIII recently, and I intended to write a straightforward review. Then I realized that was boring, so here’s a rambling essay instead…

The medium of video games encompass a broad range of entertainment, including puzzle games, racing games, musical performance simulators, and shooters. The latter category dominates American gaming in sales and typically boasts the most cutting-edge graphics.

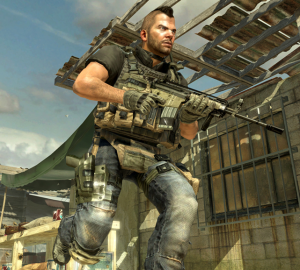

Shooters are designed to appeal to a specific audience with fairly narrow tastes. That audience is heterosexual men between the ages of 14 and 35, the same audience that goes to see every summer action movie and (in much smaller numbers) buys every superhero comic. This audience, of which I’m a part, seems to enjoy stories about rugged men doing violent things. Video game heroes are quite similar to the heroes found in most action movies: muscular, laconic, and packing enough firepower to wipe out a small country. Given these characteristics, it’s no surprise that many of these heroes are soldiers.

Master Chief of the Halo franchise

Dominic Santiago and Marcus Fenix from Gears of War

“Soap” McTavish from Call of Duty: Modern Warfare

The universes inhabited by these characters also reflect a masculine/military bias. Aesthetically, shooters often employ amazing technology to portray a very limited range of environments. It’s in the nature of shooters to take place in war zones. Whether the sterile, futuristic warships of Halo, or the urban battlefields of Modern Warfare, or the post-apocalyptic wasteland of Gears of War, these are locations for combat, not to admire the view.

Thematically, shooters also tend to focus on male preoccupations, particularly male-male bonding, strength-of-arms, and technological fetishism. Needless to say, love and relationships (besides straight male friendships) are secondary concerns at best. Women are present in some of these games, but generally in a supportive role, and they only rarely get to participate in the action. (I’m aware that there are plenty of counterexamples, but I’m not saying all American games are X so much as I’m simply noting a trend).

Things are a little more complicated in Japan. Japanese game developers create plenty of games just like Halo, but they can also create games that are so different it’s hard to imagine them ever being produced by an American company. And I’m not even talking about oddities such as “Nintendogs.” One of the most successful games to come out of Japan this year was, on the surface, a typical adventure about a group of heroes who fight monsters and enemy soldiers. The lead character is a laconic bad-ass who wields a gun-sword (it’s like a gun … but also a sword!). And she wears a skirt.

Lightning from Final Fantasy XIII

In a different game, Lightning (or you can use her far more awesome Japanese name, Raitoningu) could easily be dismissed as just another heroine who’s really a “man with tits.” But that criticism doesn’t apply very well to Final Fantasy XIII.

Unlike the bleak war zones of American gaming, the universe of Final Fantasy XIII is sparkly wonderland. The world is pretty for the sake of being pretty, and it demands that the player occasionally take some time to admire the view. And the characters don’t wear functional body armor. Their outfits are elaborate, colorful, and almost oppressively cute. They appeal to the cosplay crowd rather than military enthusiasts. In other words, this game is kinda girly.

Vanille

Hope (who is a boy, just to be clear)

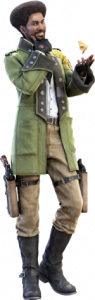

Sazh

Fang

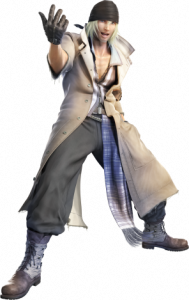

Snow

The gameplay in Final Fantasy is primarily violent conflict, but it doesn’t treat violence as a purely male/soldier activity. Women can kill monsters, men can kill monsters, cute girls can kill monsters, even a boy named Hope can kill monsters.

Violence isn’t gender-coded, partly because the cast is evenly split between male and female, but also because gender isn’t neatly defined. This is a universe where women can be named Lightning and Fang and men can be named Hope and Snow. But it’s more than just unusual names. Lightning and Fang are the most stereotypically male characters in the game: tough, aggressive, and, in the case of Lightning, emotionally distant. The men are actually more emotionally open. Snow is obsessed with rescuing his fiance, Sazh wants to save his son, and Hope is initially out for revenge (later he starts preaching the power of friendship). But the developers at Square Enix weren’t content to simply flip gender roles. The girliest character in the game, Vanille, is still a girl. Final Fantasy XIII doesn’t have bright line rules on how men and women are expected to behave.

The story is also quite different from the typical American action/adventure. The female characters don’t simply revolve around a male lead, they have relationships with each other. And the story actually focuses on the relationships between the characters and and their gradual development into a pseudo-family. None of this is meant to suggest that Final Fantasy XIII is brilliantly written. The plot is repetitive. The dialogue is clunky, and it’s made all the worse by an occasionally awkward Japanese-to-English translation. Character drama aims at being moving, but it often falls short. But regardless of its failings, it’s a story that’s about more than just conquest and killing the bad guy.

The genre is also worth noting. Final Fantasy XIII is a role-playing game (RPG), not a shooter. RPGs can be action-packed, but they also give the player the ability to control the gradual improvement (“leveling up”) of the characters. This control, as limited as it may be, gives the player a greater investment in the characters and their story. And since RPGs are about role-playing, they tend to emphasize the interaction between characters and their interaction with the environment. In shooters, story, character, and environment are typically just window-dressing for the action. Speaking from purely anecdotal experience, I’ve noticed that RPGs, and the Final Fantasy franchise in particular, seem to be very popular among female gamers. I’d wager that the reason for this is the the greater attention paid to relationships and character interaction. (And before someone accuses me of unfairly maligning all American games, there are plenty of American RPGs that offer gameplay similar to Final Fantasy XIII, though I would point out that many of them still embrace the techno-militaristic aesthetic of the popular shooters).

I wouldn’t go so far as to describe Final Fantasy XIII as a feminist game. For all it’s gender-bending, the game still adheres to a traditional view of feminine beauty. And just like American superheroines, none of the women get to wear pants. Nevertheless, it’s a game that actually has women front and center, and it passes the Bechdel Test (in case Erica is curious). More importantly, Final Fantasy XIII doesn’t treat femininity as something to be mocked or ignored. Instead, it’s an attribute that’s essential to the game’s appeal, and perfectly compatible with kicking ass.