This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

In her short story “Speech Sounds”, from the Bloodchild collection, Octavia Butler imagines a world in which a mysterious plague has robbed most people of language — both speech and written. The story opens as the protagonist, a former freelance writer who can still speak but not read, sees a dispute on a bus.

People screamed or squawked in fear. Those nearby scrambled to get out of the way. Three more young men roared in excitement and gestured wildly. Then, somehow, a second dispute broke out between two of these three — probably because one inadvertently touched or hit the other.

The first time you read this, it’s not especially clear that the combatants can’t talk to each other; their screams and squawks, gestures and roars, seem figurative — a description of chaos, in which communication becomes irrelevant because of anger and fear and violence. It’s only as you go along that you realize the description is literal; people are really screaming and squawking inarticulately, because no one can speak. A scene that seems familiar is actually strange. The people who we think we recognize as ourselves, under stress, are actually separated from us by an insurmountable barrier; we think we understand them, but we don’t; we think they are speaking to us but they aren’t. Through a trick of language, a realist anecdote becomes science fiction, and the world, and those in it, become more alien than we thought.

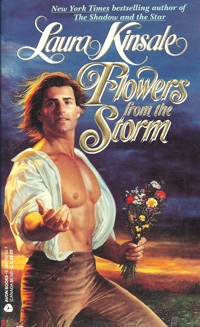

In her historical romance, Flowers From the Storm Laura Kinsale’s hero, Christian, the wealthy powerful rakish Duke of Jervaulx, suffers a brain hemorrhage which robs him of the power of speech. He ends up in an insane asylum, where he is cared for by Maddy, a Quaker and coincidentally the daughter of a friend. Jervaulx’s loss of speech seems like it should put him beyond communication, or shut down his ability to communicate with Maddy. But instead, somewhat miraculously, it makes it possible for them to love each other, both because his illness is the cause of bringing them together and by making her understand him better.

She lifted her head. He wasn’t a two-year-old. He had not lost his reason.

He isn’t mad; he is maddened.

The thought came so clearly that she had the sensation someone had spoken it aloud….

Jervaulx had not lost his reason. His words had been taken away. He coulcn’t speak,and he couldn’t understand what was said to him.

Christian’s silence enables Maddy to hear something which Kinsale strongly suggests is the voice of God. And what the voice tells her is that the stranger she thinks she sees is not actually a stranger. Through a trick of language, the other, beyond reach, becomes an intimate, and tragedy moves towards romance.

For both Butler and Kinsale, then, genre is built around language and the loss of language. And if both depend for genre on who understands what, it seems like you could understand them both as part of the same genre, depending on how you listen to them.

It’s not too difficult to see “Speech Sounds” as a thwarted romance; the main plot of the story involves the protagonist, Rye, tentatively falling in love with a man she calls Obsidian; they have sex, decide to stay together, and he is then suddenly killed. If the story starts by making you perceive the everday as alien sci-fi, it moves on to contact between stranger’s, a quick flowering of love from the storm.

By the same token, Flowers From the Storm can be read as science-fiction. It’s set in the Regency period, with rules and customs which are certainly as alien to the contemporary reader as Butler’s familiar post-apocalypse. A good bit of the story is told from Christian’s perspective, and so you see the alien world speak to him in an alien language. “Weebwell,” she whispered. “Vreethin wilvee well.” The Quaker woman, with her rituals and strange taboos (no lying, using “thee” and “thou”) is seen by Christian, too, as other and distant; he becomes the readers’ point of identification, a stranger in a strange land.

Both Butler and Kinsale are writing in a genre of difference — a genre that can broadly encompass both sci-fi and romance. This focus on difference is also, as Lysa Rivera says of Butler’s work, a focus on marginalization. Those who are seen as different are also marginal. When everyone else loses language, Rye, who retains it, becomes a potential target of jealousy and violence. Christian is rich and powerful, but when he loses language he becomes a madman, marginalized and subject to arbitrary imprisonment and punishment.

It’s significant that these differences and marginalizations are, literally and figuratively, a byproduct of language. This is true on multiple levels. Both Rye and Christian are marginal, or marginalized, because of their relationship to speech, or words. But they’re also marginalized because of their positions within an arbitrary fiction. Butler has created a future world, and placed Rye on the margins within it; Kinsale has created a past world and placed Christian on the margins within it. The characters’ struggles with language could be seen then as a kind of awareness of their own status as subjects to, and objects of, language. Their speech is wrong because they’ve been spoken wrong.

If the characters are positioned through language, the same can be said of the authors. As Rivera pointed, out, Butler’s work can be seen as marginal in many ways — it’s by an African-American woman, which is a marginal identity within science-fiction; and it’s science-fiction, which is a marginal genre in terms of literary credibility and academic interest. In comparison to Laura Kinsale, though, Butler is certainly more centrally positioned in numerous ways; sci-fi has more credibility than romance, and Butler is fairly well-established as an object of academic inquiry in a way Kinsale certainly isn’t (there’s a lengthy entry for “Speech Sounds” on Wikipedia; none for “Flowers From the Storm”). Marginalization and difference, for both authors, isn’t an absolute, but a function of their relative position to genre and to speech. Who is different, and from what, depends on what, or how, you’re talking about, or to.

So who is the person talked to? Arguably it’s you, the reader. In both Butler and Kinsale, language positions you as other, trying to understand, and as intimate, comprehending and empathizing. Language alienates and seduces; it conveys the terror of difference and the joy of bridging it — or, alternately, the joy of difference and the terror of bridging it. Language, that intimate betrayer, makes you each book’s monstrous invader, and each book’s lover.