I had somehow missed The Silence of the Lambs, viewing it only a few years ago, well into my adulthood. After years of making jokes about how “it rubs the lotion on its skin,” my husband got frustrated with my blank looks of incomprehension and queued it up on Netflix. As Buffalo Bill grows increasingly irate with his captive, screaming at her “or else it gets the hose again!”, I burst into tears. A 30 year old woman frantically crying over an often-mocked scene in a 20 year old film.

My husband was unnerved to say the least—he had seen the film when it came out, and since it circulated in popular culture in a recognizable way for him, the line had lost its teeth. It was cheesy, and morphed into a joke. I, on the other hand, had no context for the line, and had heard it for years as a cutesy phrase that referenced a film I’d never watched. Having it replaced in its proper milieu was jarring. Instead of a tacky scene worthy of ridicule, something about the pronoun—“it”—and the directive about lotion reached around the rational part of my mind and struck me directly in the amygdala.

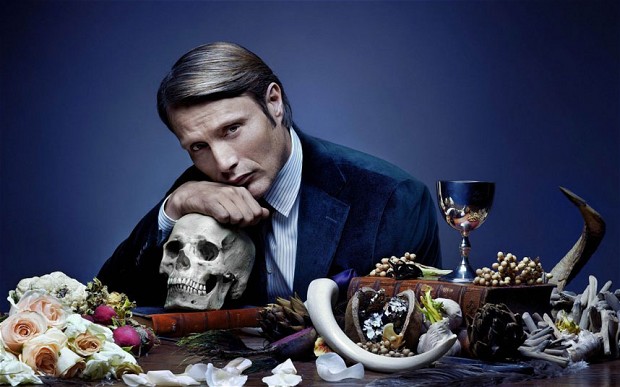

I unintentionally overlooked the television series Hannibal until two seasons in, when I was looking to kick off last summer with some horror. The glorious cinematography, the powerfully reserved acting, and the beautifully rendered script combined to make a stunning and tense dance of intellect and gore.

The first and second seasons are fixated on the strain between knowledge and ignorance. Will Graham, a special investigator for the FBI, is capable—according to Dr. Lecter—of “pure empathy”; he can mentally reconstruct a murderer’s actions, playing the role of the criminal in his internal recreation of the drama. Special Agent Jack Crawford contacts Will to assist him on a case in which young women of the same physical description have been disappearing. Crawford’s initial role is less that of a capable investigator than a pushy delegator. Dr. Alana Bloom, a purportedly intelligent psychiatrist, has taken an interest in Will, and wants to protect him from what she sees as Crawford’s potentially disruptive pressure. To this end, she introduces Crawford to Dr. Hannibal Lecter, who is tasked with monitoring Will.

The show relies on the audience’s pre-existing knowledge of Dr. Lecter operating in the background. Assuming we have seen the unhinged Anthony Hopkins biting the cheek off of a prison guard and recounting eating a liver with “some fava beans and a nice Chianti,” we are faced instead with an eminently rational and restrained Lecter in the show.

Lecter’s self-possessed mien in Hannibal stands in stark contrast to Hopkins’ portrayal, and while the audience knows he is the “bad guy,” the show operates less on the shock value of the murders under investigation or Lecter’s own gastronomical vagaries, and more on how power and knowledge must be—as Michel Foucault insisted—thought together.

Foucault equated knowledge with power, something that those currently struggling under the auspices of austerity in the academe may find laughable, but it’s an equation that is nonetheless compelling for situating current debates about the role of those with knowledge, and what types of knowledge can (or should) be leveraged into power. In Hannibal, Lecter uses his intellect, as well as his privileged status as confidant and guide for Will, to conduct increasingly bizarre experiments on him while the latter is in a fugue state. Lecter manipulates those around him, relentlessly curious about the boundaries of goodness and empathy in those who have the capacity for them.

Foucault is careful to distinguish between knowledge that is laden with power and knowledge that is marginalized. He specifically notes the “disqualified knowledges” of the mentally ill, but broadens this to say that “We are concerned, rather, with the insurrection of knowledges that are opposed primarily not to the contents, methods, or concepts of science, but to the effects of the centralizing powers which are linked to the institution and functioning” of a discipline (Power/Knowledge 84). In regards to this, he parses the way in which power is only thought of as something that is exerted, rather than something that is naturalized and replicated without direct activity.

As shorthand, it can be thought of as the distinction between the power of having and the power of doing.

Hannibal’s ability to unnerve and disquiet rests not on the “reveal,” as with many crime thrillers. The audience already knows who the villain is, even as the team tries to sort out other cases of varying drama and terror. Instead, the appeal of Hannibal rests almost entirely with the tacit knowledge shared by the audience and Lecter: that he is the antagonist, but we still want to see precisely what he is capable of in relationships. In fact, the least interesting scenes in the show are those that depict him enjoying a meal of a person alone. The tension instead resides in watching Lecter use the knowledge he has of himself—as well as his developing theories about other characters—to his own ends.

I’ve been reflecting on Hannibal throughout the year because its peculiar blend of refinement, psychopathology, and epicureanism holds me in a strange thrall. It reminds me of other debates about power, both the having and the doing, because the show has crafted a world in which the rules of behavior and the exercise of power are nearly illegible to those in the best position to address the atrocities occurring within their midst.

In particular, as I watch the third (and possibly final) season of Hannibal, I’m also embroiled in the ongoing debate about campus sexual harassment, launched in part by Laura Kipnis in her now-famous Chronicle of Higher Education article “Sexual Paranoia Strikes the Academe.” This may seem an odd pairing—a show about a psychiatrist/cannibalistic serial killer and a turgid debate about whether or not professors should be permitted to have sex with students—but I can’t help but think that the same questions about power are at stake.

For those who haven’t followed the discussion, Kipnis’s argument rests on three major elements. The first is that administrators are overstepping their boundaries and are infringing on academic freedom. This is patently true, and doesn’t merit debate. Administrative overreach has been consistently critiqued over the past 30 years, and is getting worse as faculty are increasingly shifted to the status of contingent labor. Furthermore, because of this administrative overreach, it is increasingly clear that non-educators are determining educational policy, always to the detriment of students’ actual development.

Second, she contends that an obvious example of this is new policies prohibiting professor-student romantic relationships. These policies have been implemented at a variety of universities to quell the tide of demonstrations against campus sexual assault. While I personally agree with these policies, I can see the potential problems with them, and am willing to debate them.

Third, she argues that the supposed “sexual panic” on campuses is vastly overinflating a relatively benign problem, and that students’ own sense of exaggerated vulnerability is actually making professors the more vulnerable class. This is ridiculous. Professor-on-student sexual harassment and assault are still significant issues. While student-on-student sexual harassment accounts for 80% of reports on campus, that still leaves a sizable problem. Furthermore, many cases of both varieties go unreported. For example, Kipnis asserts that

For the record, I strongly believe that bona fide harassers should be chemically castrated, stripped of their property, and hung up by their thumbs in the nearest public square. Let no one think I’m soft on harassment. But I also believe that the myths and fantasies about power perpetuated in these new codes are leaving our students disabled when it comes to the ordinary interpersonal tangles and erotic confusions that pretty much everyone has to deal with at some point in life, because that’s simply part of the human condition.

Here, she is conflating normal misunderstandings with harassment.

My annoyance with the tenor of this discussion has increased with the tone-deafness of Kipnis’ understanding of power and its subtle manifestations.

In Hannibal, the audience is in reluctant collusion with Lecter as he manipulates and slaughters characters. There are—of course—the “ordinary interpersonal entanglements” of daily life. Will Graham and Alanna Bloom share an attraction, but because Alanna is concerned about Will’s mental state, she refuses to enter into a relationship with him. Jack Crawford’s pressure on Will to use his empathy can grow harsh. However, standing in stark contrast to these relatively benign interactions is the maneuvering of Lecter.

Interestingly, both Will and Lecter work from the point of curiosity about human emotions and motivation. While Will is able to adopt the perspective of others who have committed misdeeds in the past, Lecter is able to use his observations to predict future behavior. Both are talented, but only one begins the series with a sense of the way in which his knowledge brings him power. In the first season, Lecter experiments on Will after discovering that he has the symptoms of encephaly. Instead of seeking surgical treatment for his patient, Lecter devises a series of experiments in the clinical setting to encourage Will to lose time. In entrusting his mind to another, Will is violated at both the psychological and bodily levels because he fails to discern how this power can be leveraged against him.

After Will reconstructs a crime scene that includes a grisly totem pole of bodies, he loses time and appears at Lecter’s office door. Lecter tells him that this is the result of his psyche “enduring repeated abuse,” and Will frantically objects that “No, NO! I am NOT abused!” Lecter repeats that Will has an empathy disorder, and that disregarding his disordered psyche is “the abuse I’m referring to.” Here, abuse is relocated as being the act of the person suffering—abuse at his own hand—rather than being visited from the outside. This recalls Kipnis’s argument that it is students’ sense of vulnerability, rather than objective conditions in which they are disempowered, that is the problem.

Will wants to find a physical—objective—cause for his disorder. The viewer already knows that Lecter is hiding some aspect of this from Will, but it is not until the following episode that we see there is indeed a physical cause for Will’s rapidly fraying sanity, a cause that Lecter pressures the neurologist to conceal. Much like the objective problem of sexism within the academe, Will’s disordered brain matter has psychological effects that are erroneously attributed to more ethereal causes.

It is not that Will or Lecter stand in an easy allegorical relationship to students and professors in relation to Kipnis’s argument. Instead, Will and Lecter represent two distinct modes of knowledge, both of which are necessary to understand the real causes, circumstances, and consequences of sexual harassment in the academy and elsewhere. Lecter has power in his superior knowledge of the mind, and is not afraid to leverage it to his own ends. In this sense, we must remember that knowledge is not equivalent to ethics.

Will, on the other hand, has the capacity to understand others on an experiential level—to feel as they feel—but this very gift is also potentially disabling. Neither emotion nor reason are able to wholly grasp the diegetic world of Hannibal. Instead, there is a third term—power, and its subtle operation—with which all of the characters in both the on-screen and real-world dramas must contend.

It would be foolish, however, to equate Lecter’s power with his capacity to do violence on others. Violence is almost beside the point of the show, much like violence is frequently beside the point in terms of sexual violence. It remains popular to say that “rape isn’t about sex. It’s about power.” However, too often, those who remark on this conflate power with violence, as if violence is the only way in which power operates. Power in the world of Hannibal is not Lecter’s murders, or the murders by other various and sundry psychopaths populating the chorus of the show. It is the leveraging of psychological force.

One of the greatest myths that persists to today is that sexual harassment, and sexual violence, are invariably violent in the traditional sense of the word. The ham-handed training on sexual harassment provided by private companies making money off of universities trying to comply with Title IX do little to help this issue, as they have themselves a vested interest in concealing how subtly power circulates in a workplace, classroom, or clinic.

Perhaps this is less than legible for those who have acclimated themselves to shows of force. For example, Mads Mikkelsen, the actor who plays Lecter in Hannibal, was recently featured in Rihanna’s new video “Bitch Better Have My Money.” The video represents Rihanna as a kingpin of some sort whose accountant, Mikkelsen, has stolen her money. She kidnaps and tortures his wife, which doesn’t particularly phase him, so she goes on to torture him.

The video is an interesting contrast to Mikkelsen’s role on Hannibal. While he is still situated in relatively luxurious surroundings, he is ultimately at the whims of Rihanna. Furthermore, some critics have levelled the charge that the video is misogynistic because of the violence she visits on the woman who plays the wife of Mikkelsen. Speculations flew about whether or not this was a revenge fantasy about Rihanna’s real-life former accountant. Feminists of color have (rightly) pointed out that white feminism hasn’t always been welcoming to women of color.

Even the debates surrounding this video illustrate how fraught power is, particularly in relation to those who have been historically oppressed. Of course, the theft of money and sexual harassment or assault are not equivalent. Instead, this clearly illustrates how the public tends to react to obvious displays of violence—particularly from a disadvantaged woman, and in this case, particularly a woman of color—versus its critical acclaim of a white man with an advanced degree who eats people.

Hannibal is more than a show about a dude with “refined tastes,” however. It’s a series that best hits its stride when the audience is gazing on the beautifully plated delectables we know for a fact are composed predominantly of the minor character killed off in the previous scene. It’s a series that does more with an eyebrow raise, a small hand gesture, or a mild remark, than most shows are capable of doing with an ample explosives budget.

And it is loved—and found disturbing—precisely because we recognize that the power wielded by Lecter is at its most insidious when it is least obvious.

Obvious displays of power are few and far between. It would be delightful if tomorrow I could wake up in a world where power had shifted so far from the hands of professors and administrators that students weren’t threatened in a variety of ways by their moods and their decisions. Lecter remarks late in the second season that “Whenever feasible, one should always try to eat the rude,” but even at this point, Lecter still knows much that Will does not.

After all, Hannibal kills both for pleasure and for necessity. He only eats those he considers equivalent to the animals most humans ingest. As he remarks to a character he’s keeping captive, “This isn’t cannibalism, Abel. It’s only cannibalism if we’re equals.”

And so goes Kipnis’ argument. It is only sexual harassment if we pretend that we are equals, and that there are not small, subtle (or even obvious) power dynamics at play. It’s only violence if it looks like it to her.

Power isn’t merely in the exercise thereof. It is in the ability to assess whether or not it was exercised.