“The dream has grown gray. The gray coating of dust on things is its best part. Dreams are now a shortcut to banality. Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves the outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours.

…which side does an object turn toward dreams? What point is its most decrepit? It is the side worn through by habit and patched with cheap maxims. The side which things turn toward the dream is kitsch.”

“Dream Kitsch“, Walter Benjamin

The destructive effects of time especially in an era of rapid advances in technology and industrialization; making the implements, furnishings and fashions of not so long ago or even the generation before seem old and “musty.” It is a problem which doesn’t seem to have left us in the intervening years since Walter Benjamin wrote extensively on kitsch and its relevance to history, nostalgia, objective truth, and art.

Like the seemingly deficient 19th century artistic draperies Benjamin cites (via the architectural critic, Sigfried Giedion) in The Arcades Project, these rejected artistic mannerisms of an earlier age were then taken up by the Surrealists active during Benjamin’s life time. They, far from casting aside these old, tired forms embedded them in their work. We in turn, Benjamin adds, “would recognize today’s life, today’s forms, in the life and in the apparently secondary, lost forms of that epoch.”

* * *

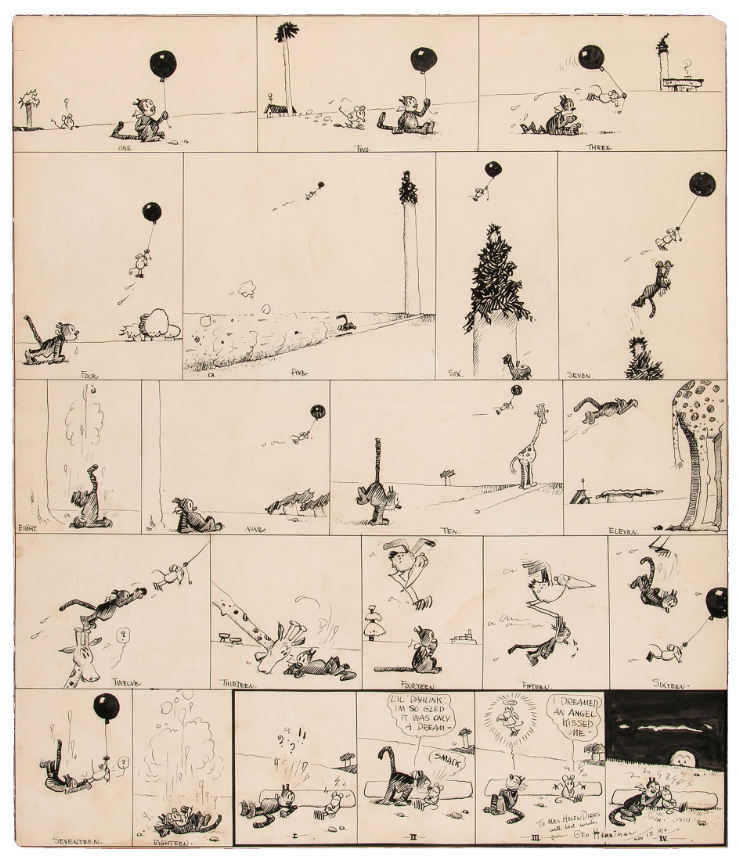

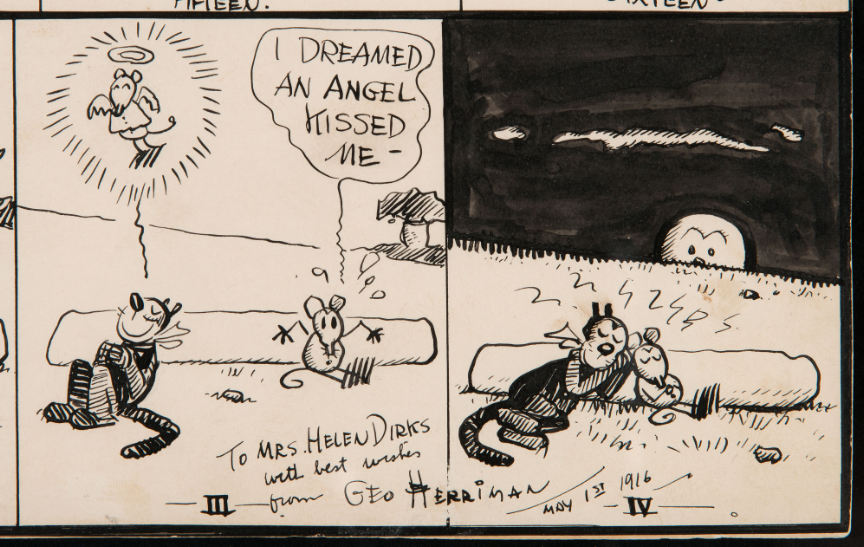

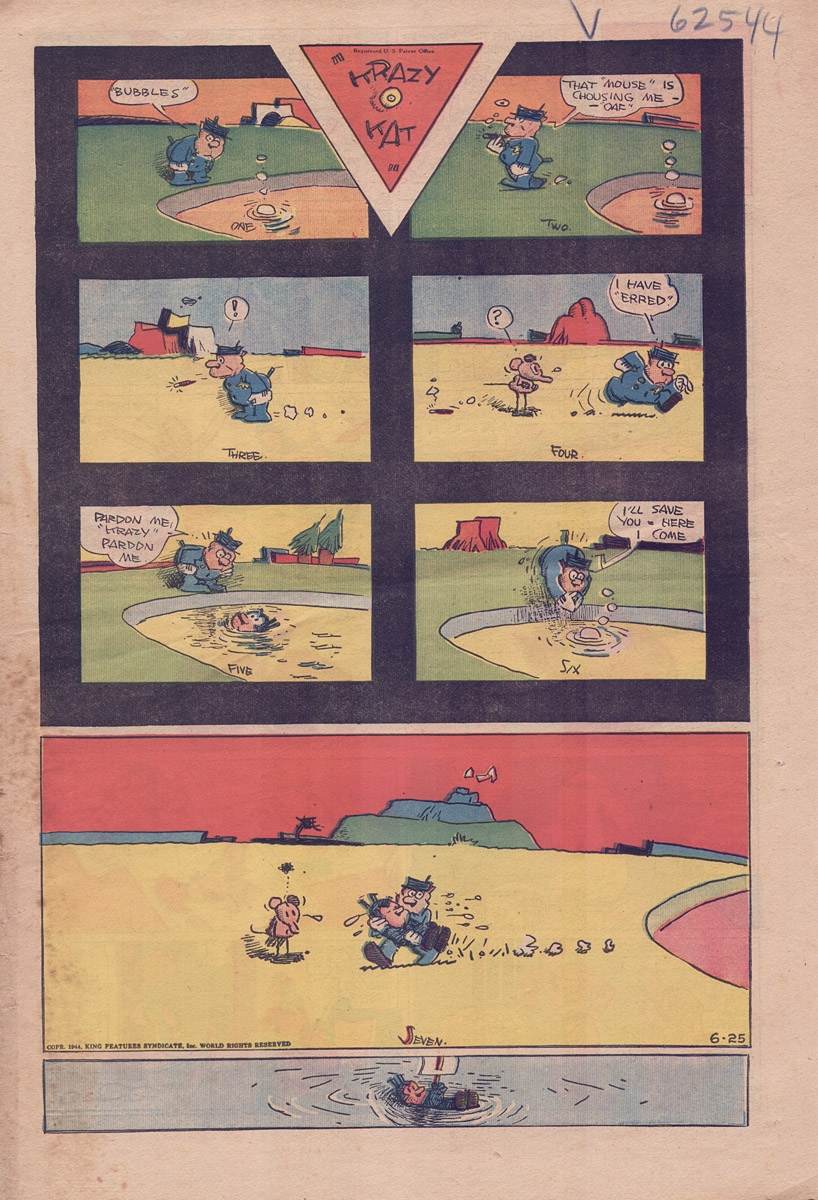

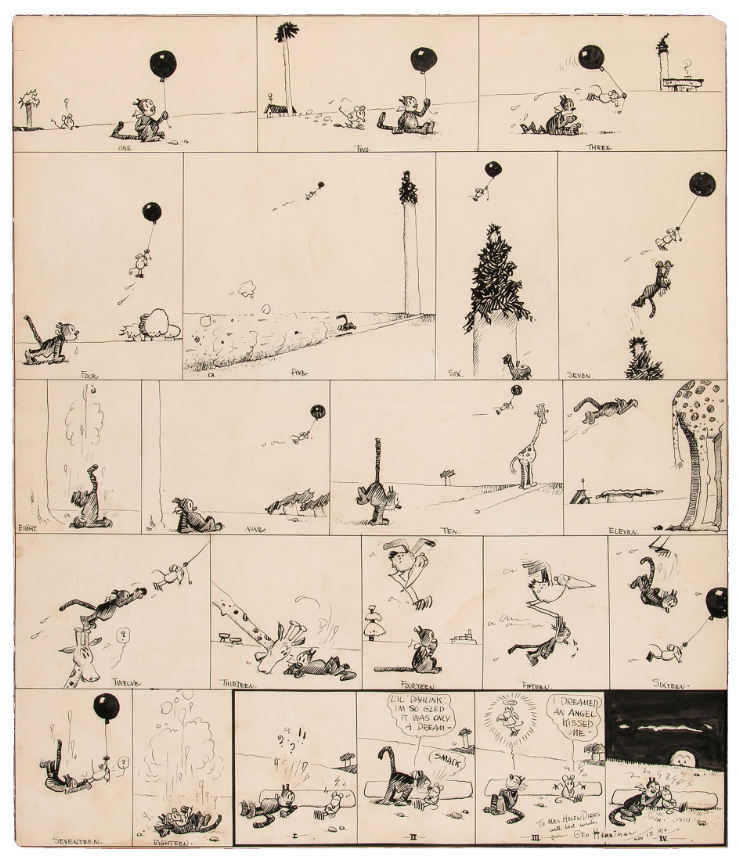

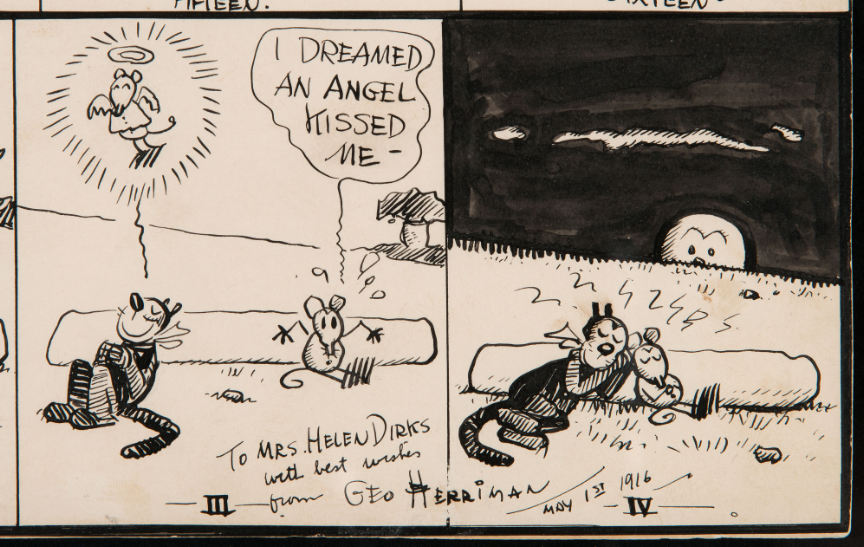

Krazy Kat Sunday 4-30-1916. The second Krazy Kat Sunday to be published and the oldest one known to exist in the form of its original art.

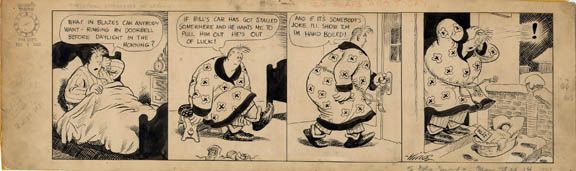

It is easy to think of cartoonists from an earlier age as being purely instinctual, producing images on a treadmill and dropping images on to the paper even as the ideas occurred to them; never completely conscious of their abilities to create lasting art. Perhaps it is a feeling gleaned from our experience with the flaccid strips of our modern age.

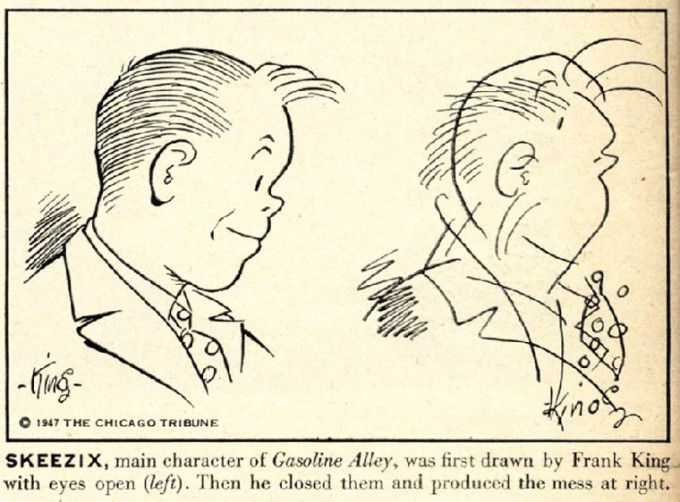

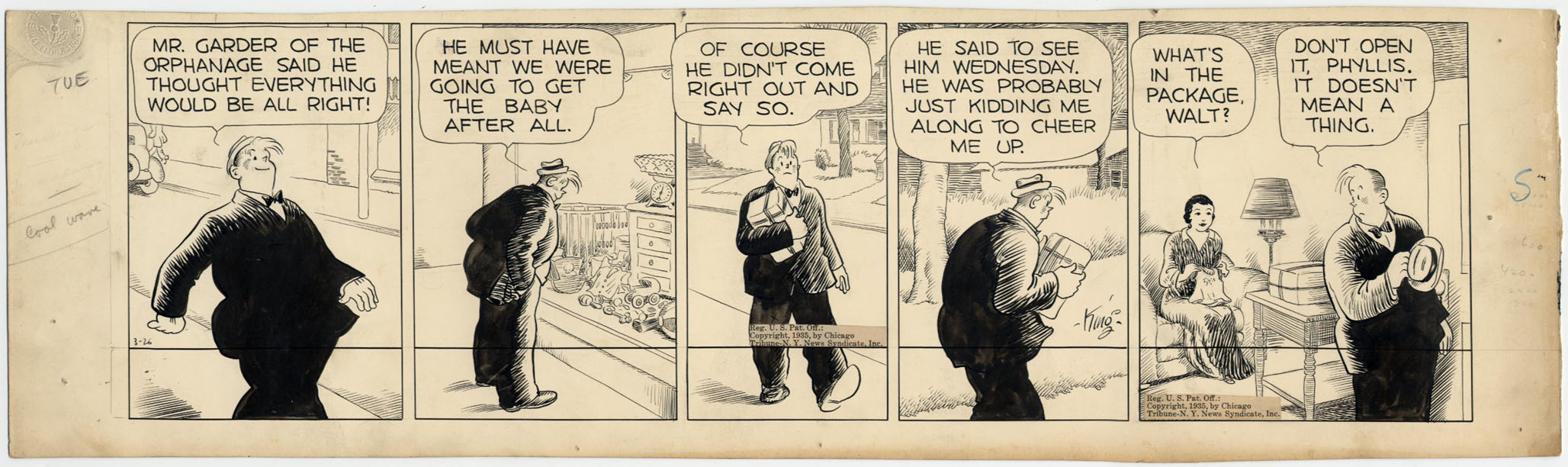

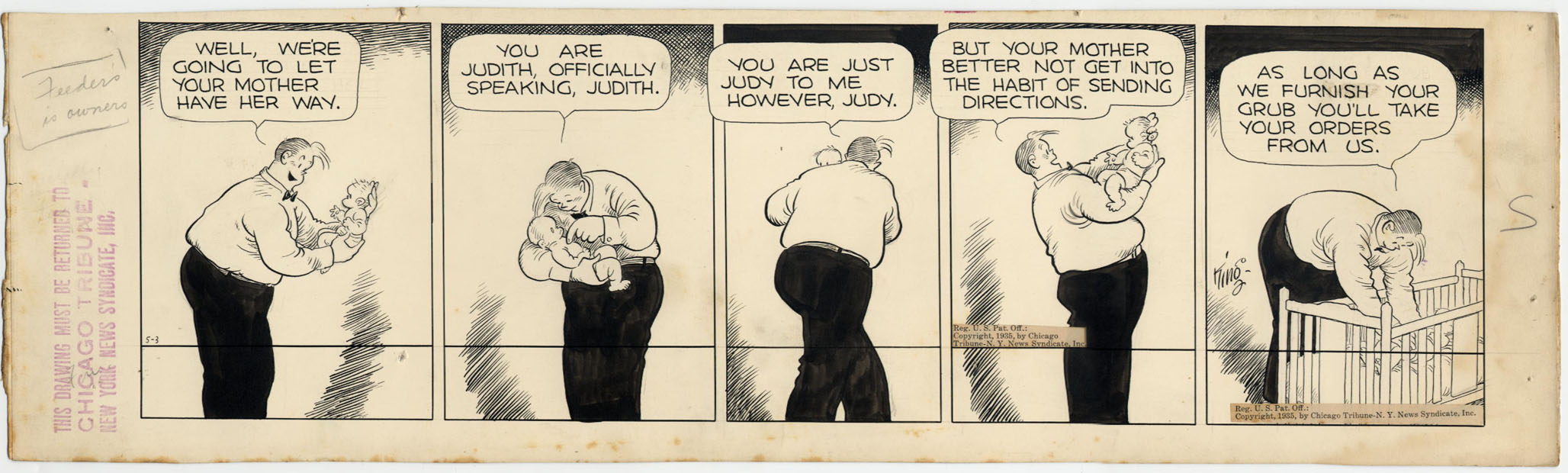

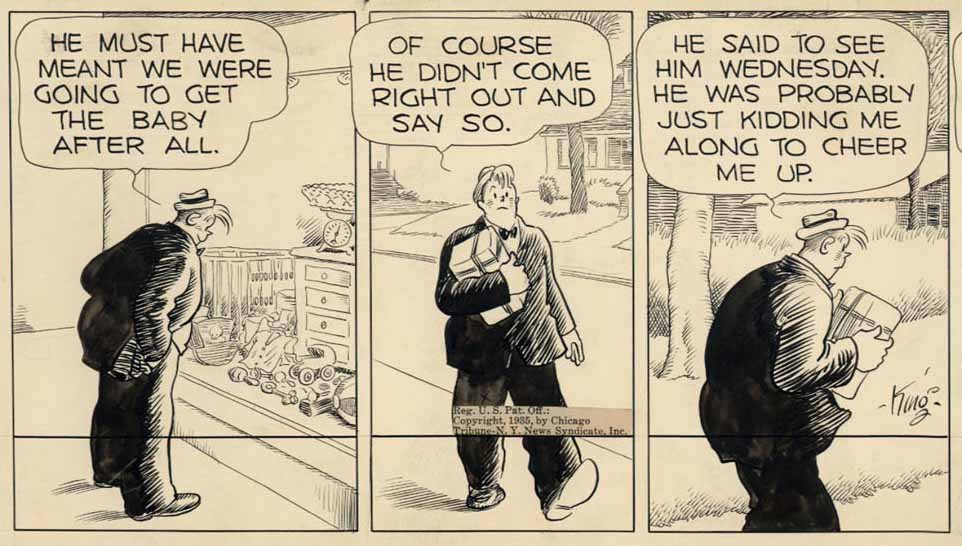

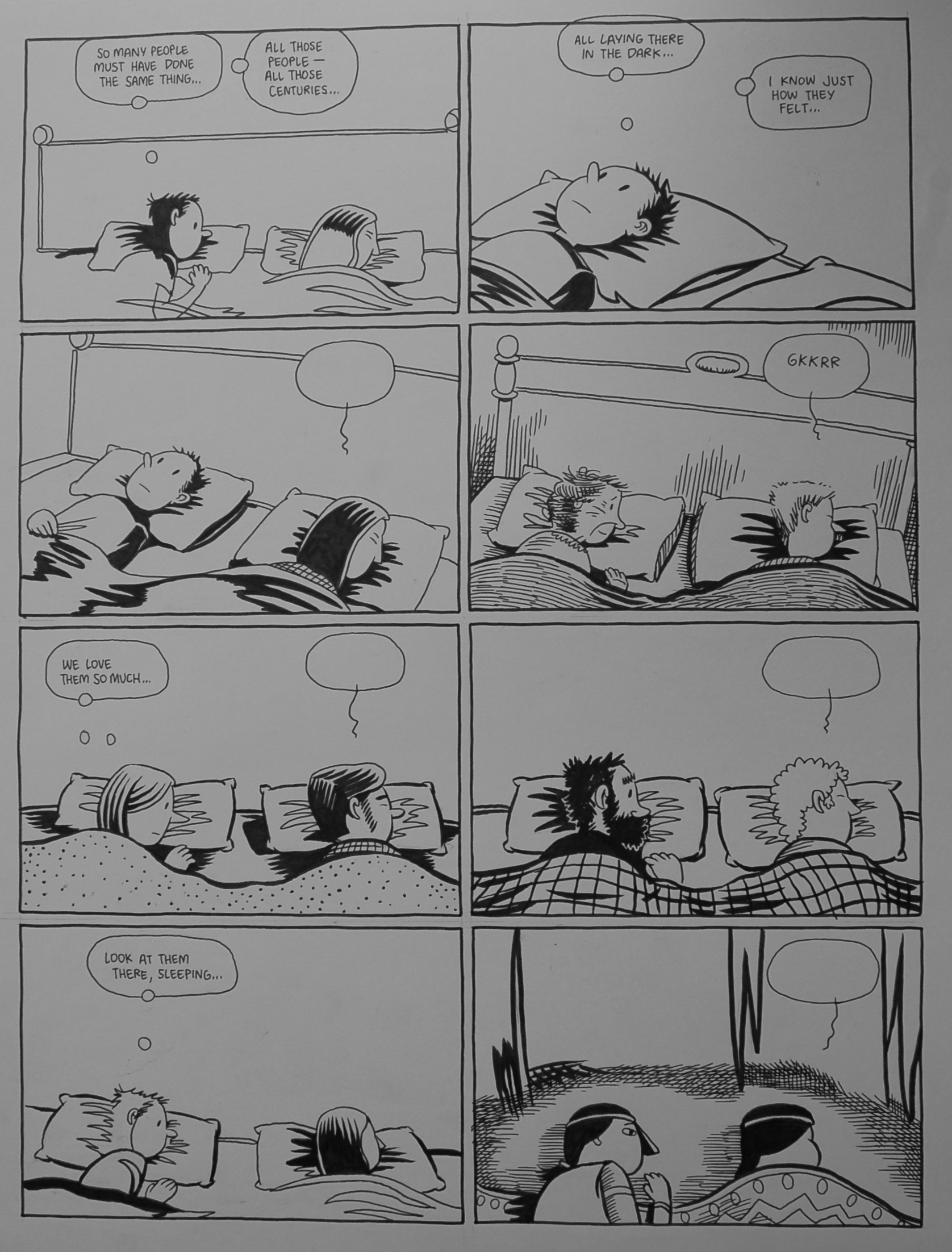

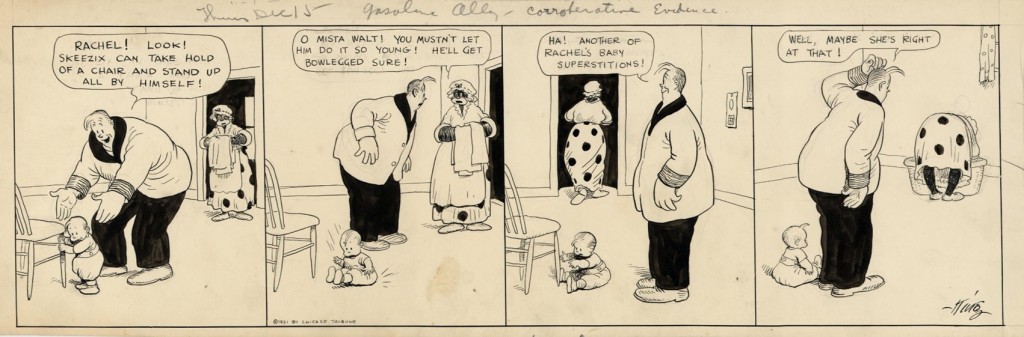

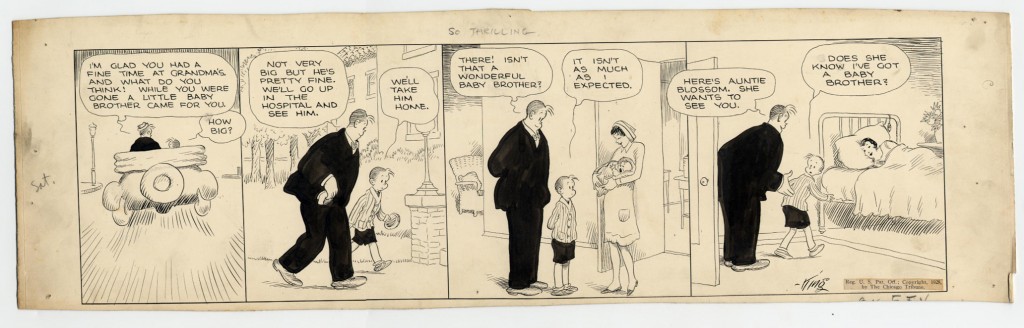

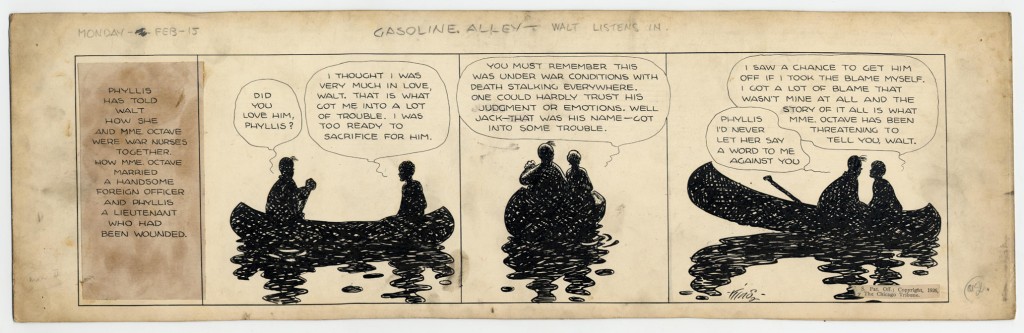

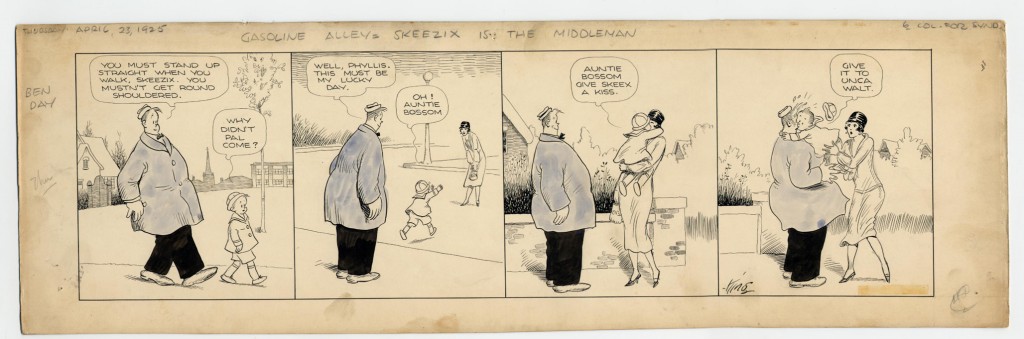

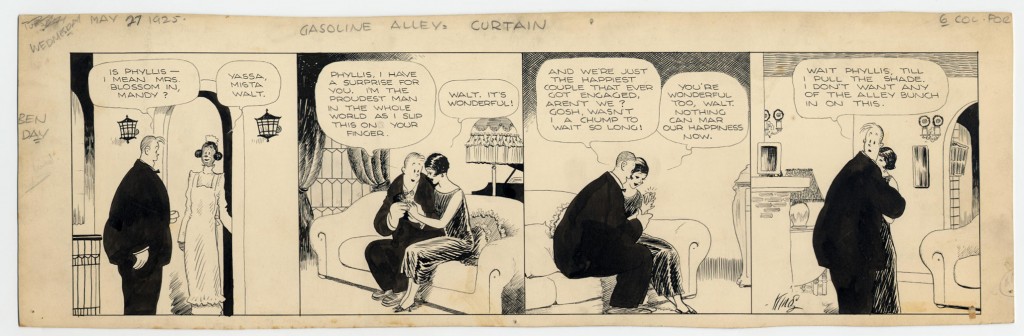

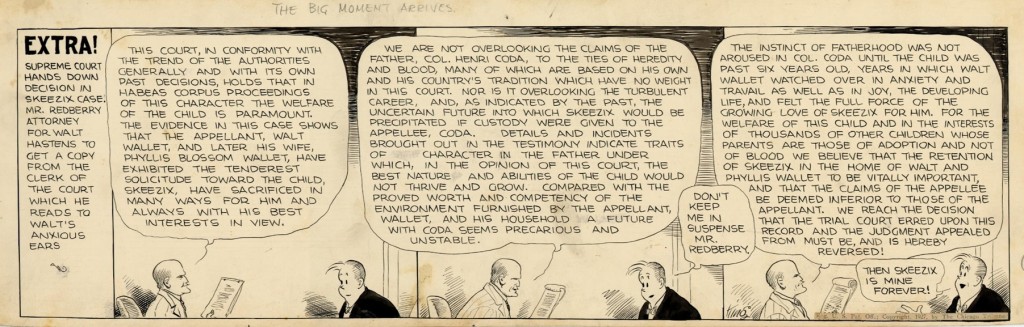

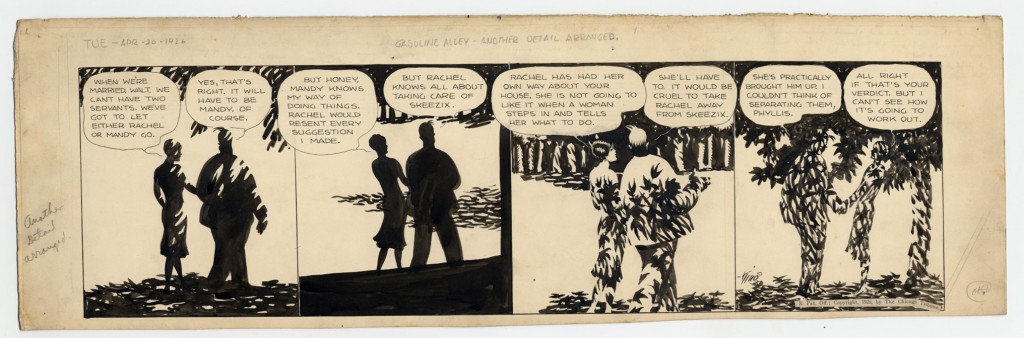

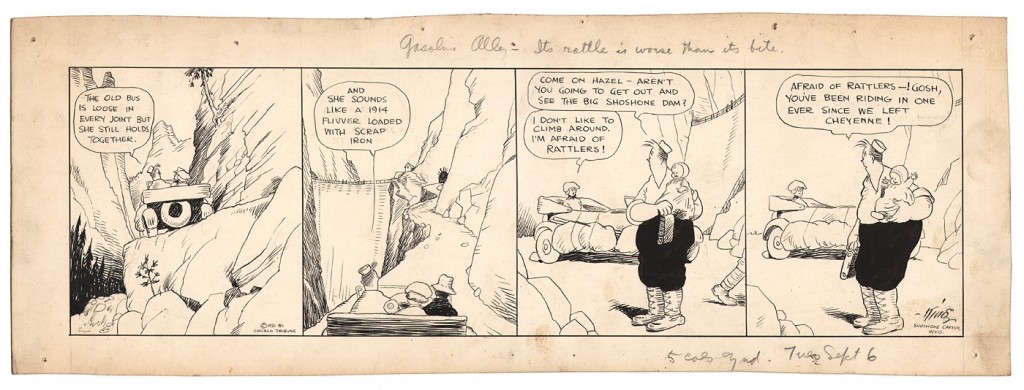

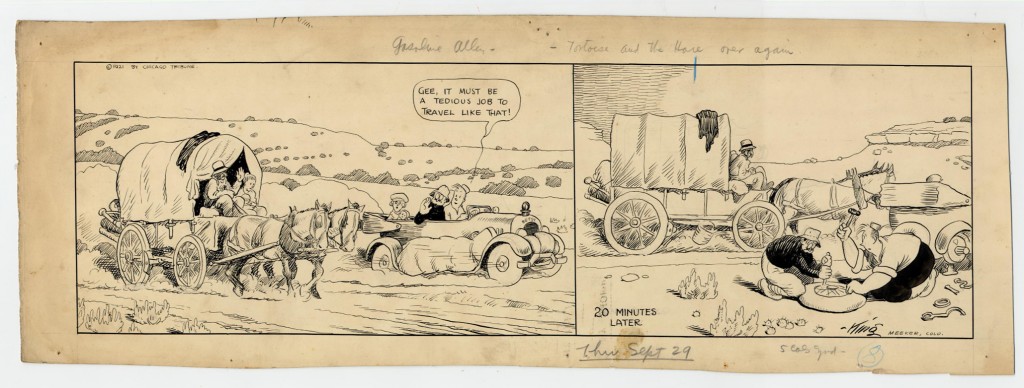

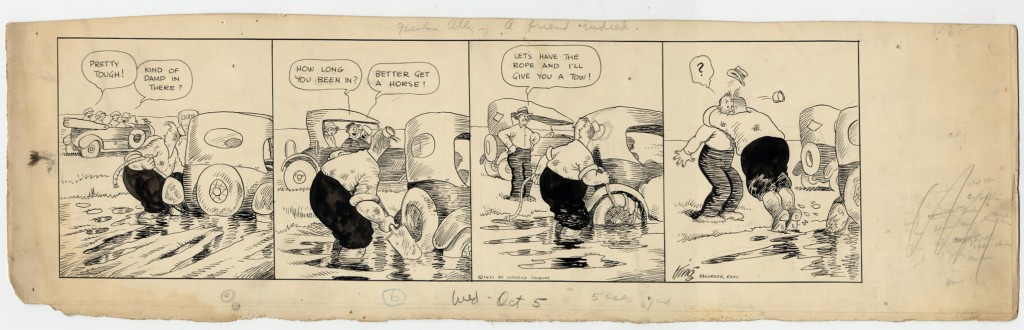

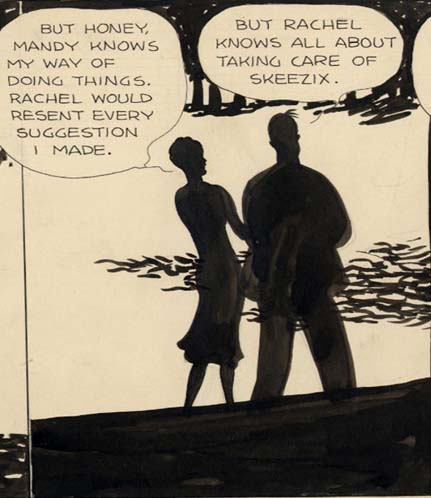

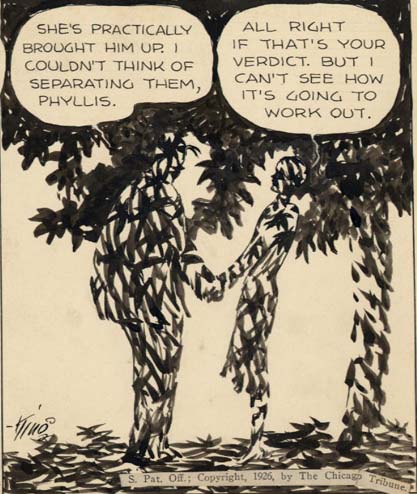

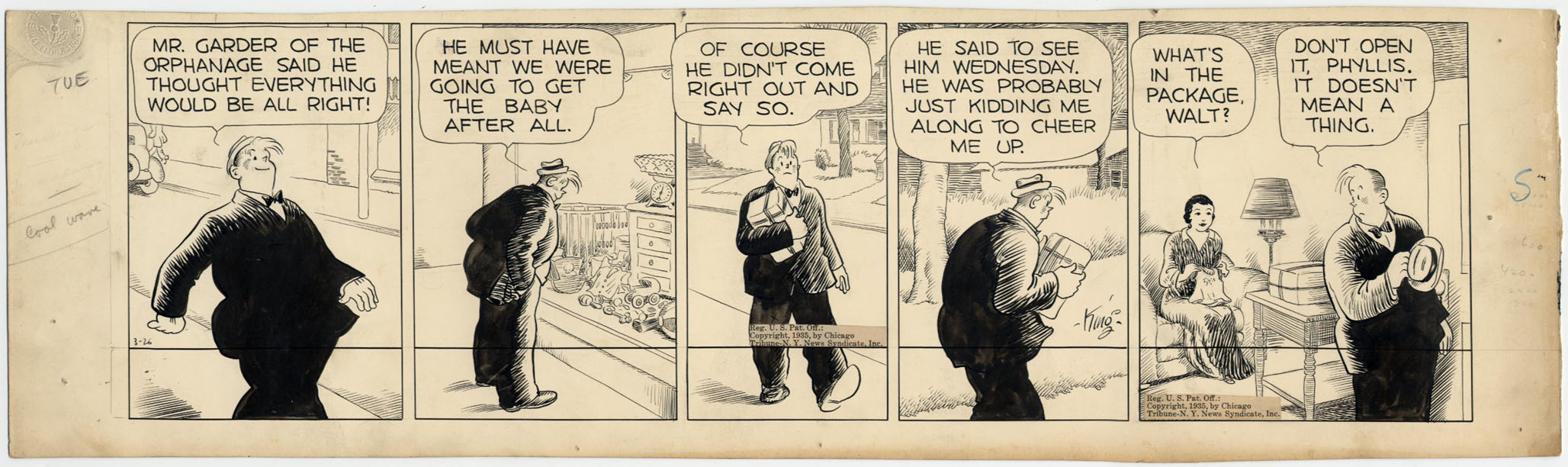

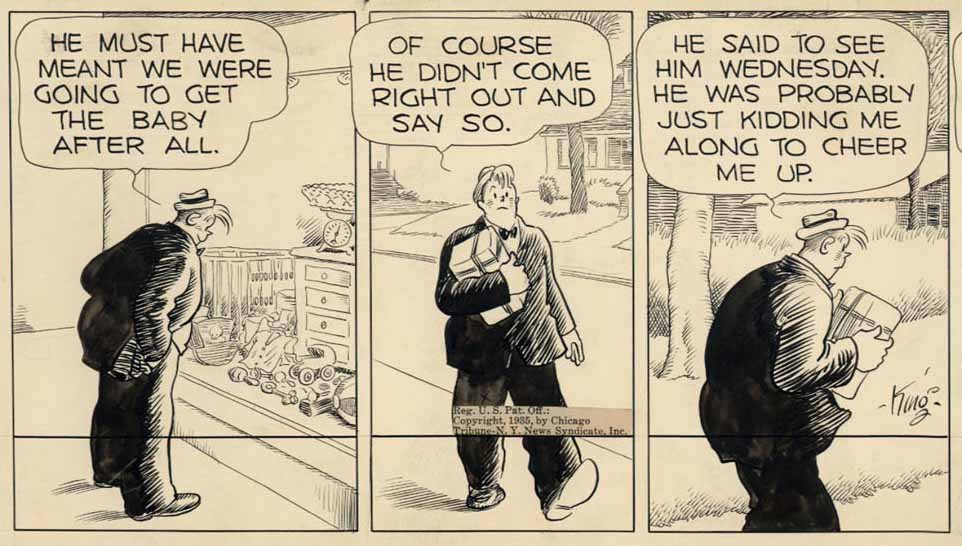

Yet even the true grind of a daily strip like Frank King’s Gasoline Alley—where readers were expected to be more interested in character and event than formalism—suggest otherwise, often allowing a level of sophistication which can be surprising. Consider the Gasoline Alley daily of 3-26-1935 where Walt Wallet frets over the adoption of his eventual daughter, Judy.

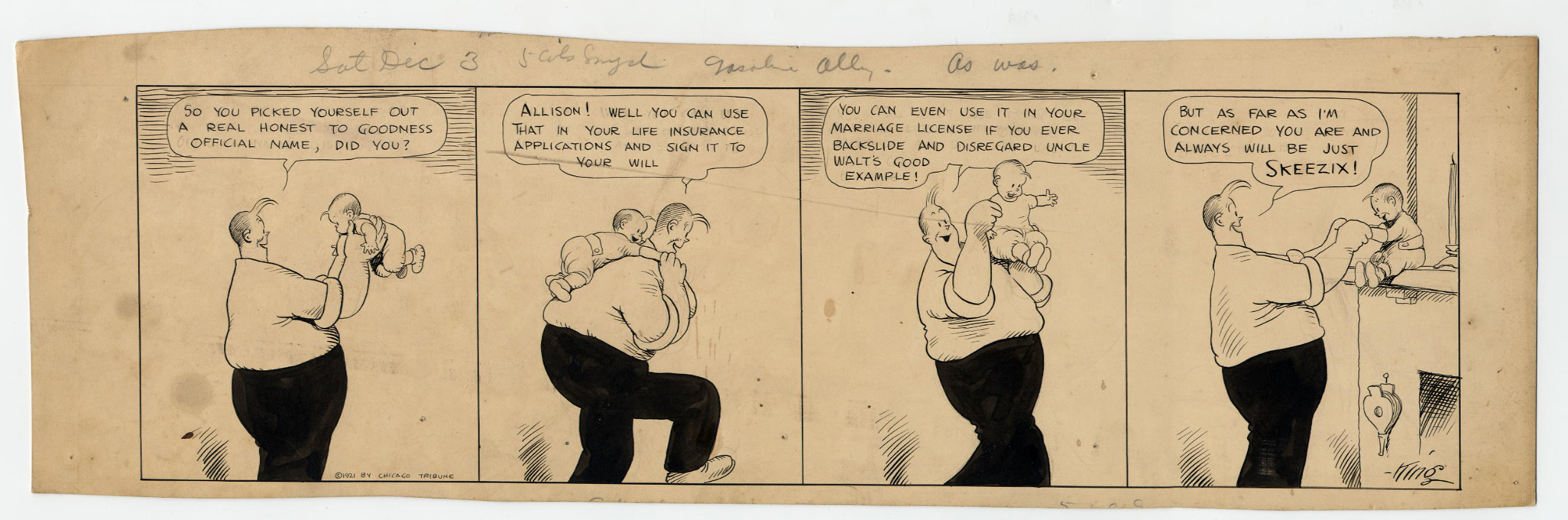

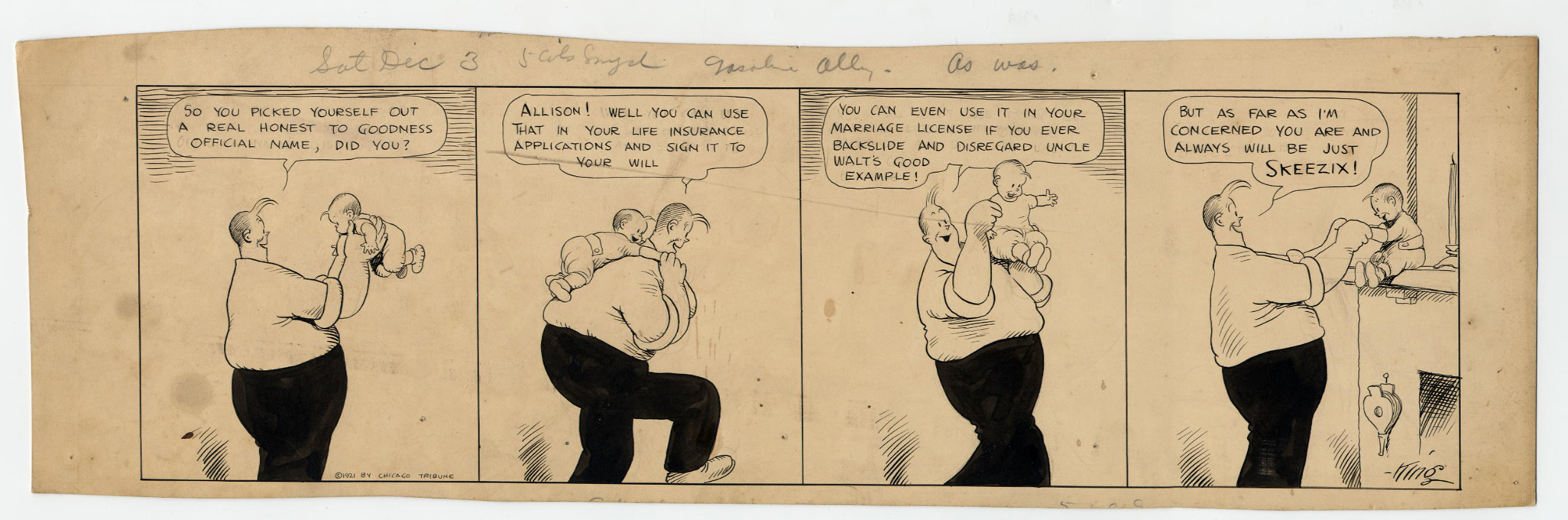

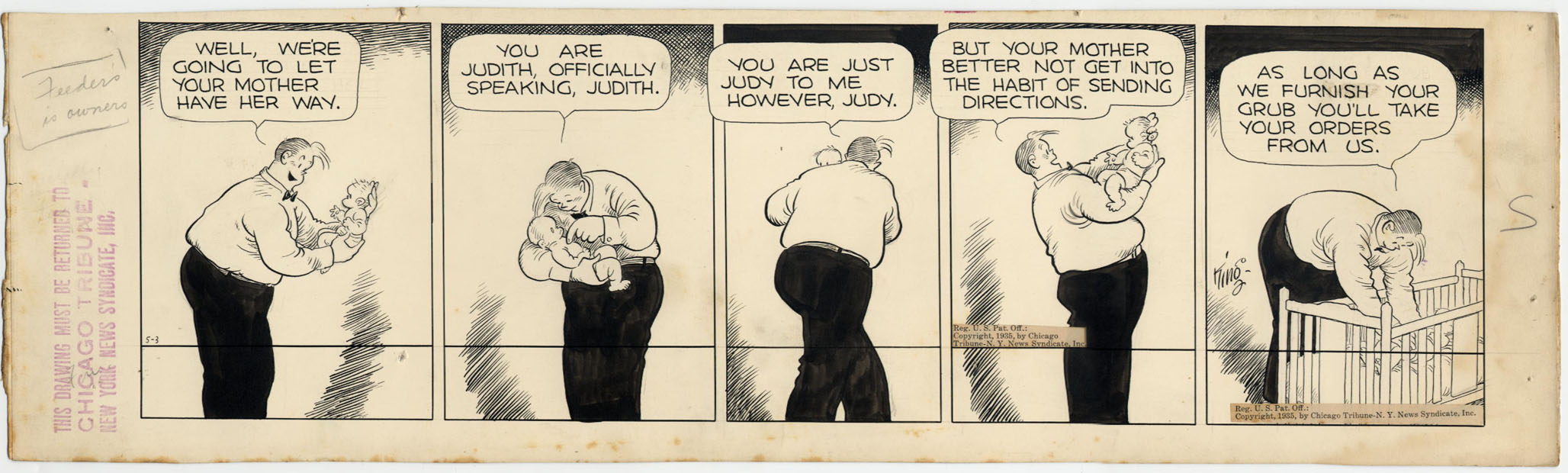

Judy was found in Walt’s car in much the same way Skeezix was discovered at his doorstep over 10 years prior, a point which King affirms by reproducing the same naming sequence for Judy which he once used for Skeezix 15 years before on 12-3-21.

One wonders whether readers at the time would have been able to remember this without a personal collection of newspaper clippings. This mirroring seems to have been done largely for the artist’s personal satisfaction (both strips were kept by King till his death).

Those seeking examples of symmetry in form and story in comics might point to the Schuiten brothers work on Nogegon or Moore and Gibbon’s “Fearful Symmetry” from Watchmen #5, but King’s daily presents itself as an early American example of this type of formalism. Walt’s strutting gait and anticipation in the first two panels are mirrored in the final two panels depicting despondency and hesitation. The shape of the panels direct the reader’s mind to this intention which is reflected fully in Walt’s posture and his words.

So it is with the Krazy Kat Sunday first mentioned above with Krazy at rest or plummeting in every other panel on left side of the Sunday page, and airborne in all the panels on the right (one should not doubt that the figures sleeping with their heads together in the final panel are in fact in flight). Herriman separates dreams from reality by means of a boldly rulered box joining the final four panels but this line of demarcation is an illusion—the dream in all its anxiety, desire, and fulfillment has not ended.

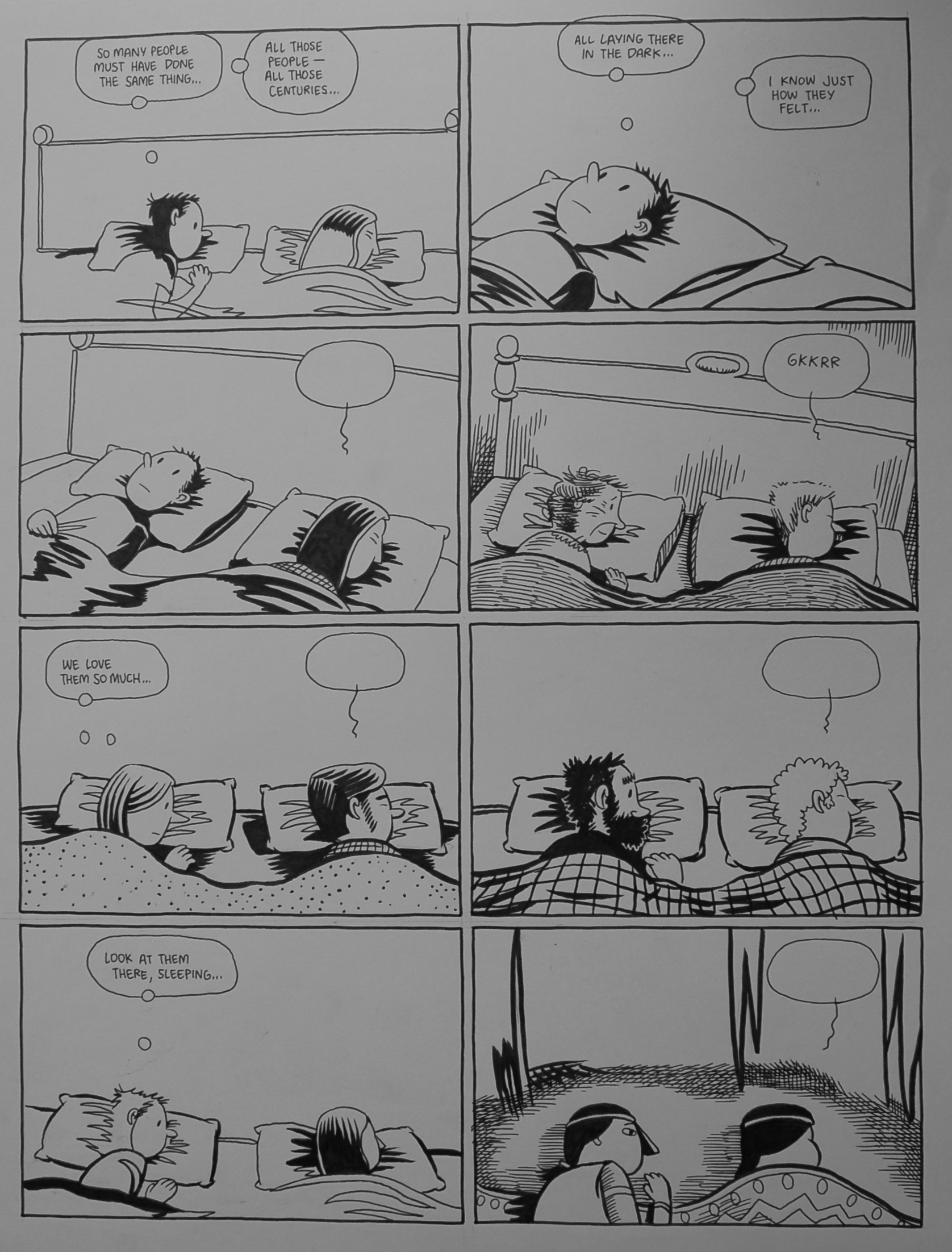

The Sunday is dedicated to Mrs. Helen Dirks (the cartoonist Rudolph Dirk’s wife) and is the very picture of conjugal bliss—the perfect kiss coupled to an absolute faith that love has been requited. A moment reiterated nearly a century later in the pages of Kevin Huizenga’s story in Ganges #1 where a lover thinks silently through the night about the person sleeping beside him—a captive moment reiterated six times on a single page where readers are asked to remember and think to themselves, “I have seen this” or “I have experienced this.” Or “Yes, this can happen” or “I wish it did happen.”

The movement and progress of the balloon which draws the mouse, Ignatz, away from Krazy may seem like an exceptional example of Herriman’s absolute control of the Sunday page and composition, but at its heart it is a vaudevillian depiction of the fear and the pain of separation; perhaps even of grief, a feeling which C. S. Lewis once described as being “like fear…[perhaps], more strictly, like suspense. Or like waiting, just hanging about waiting for something to happen.”

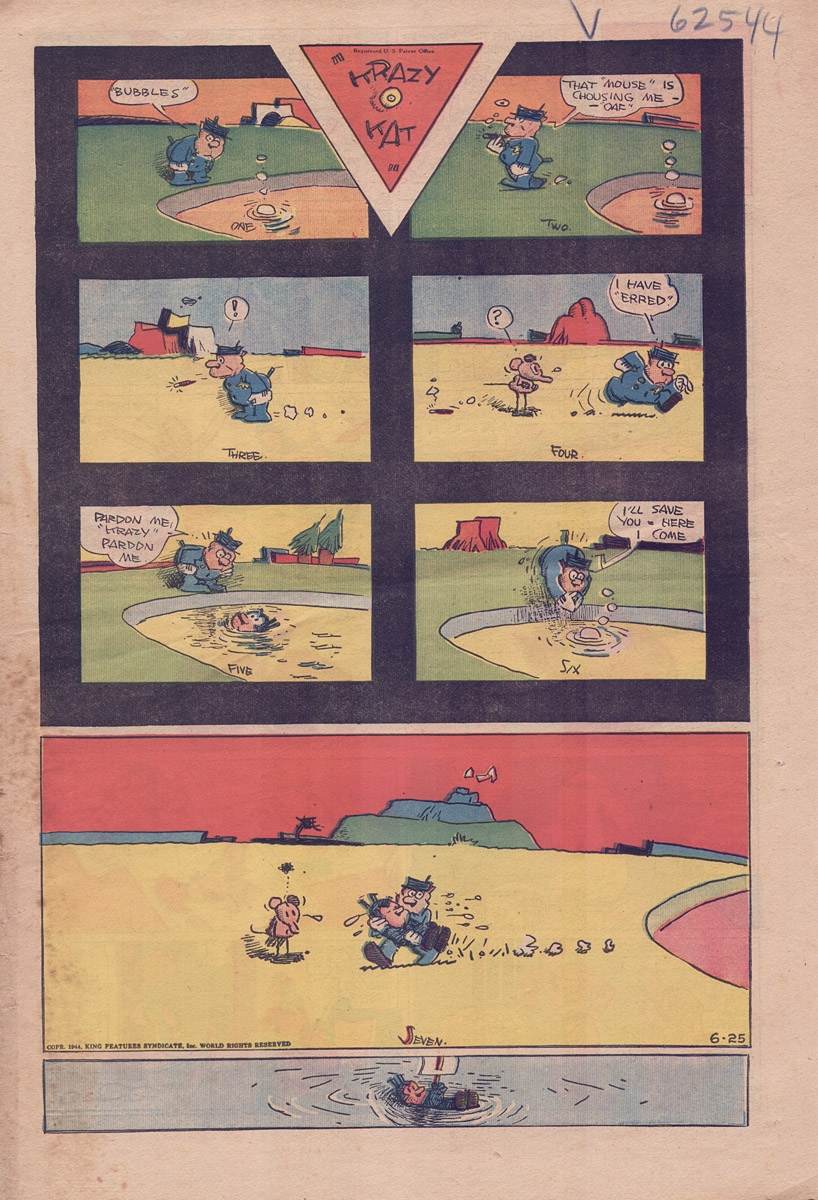

Which makes that consummate final panel altogether more poignant, especially if one thinks back to the final Krazy Kat Sunday in which Krazy is seen drowning alone in a pool riddled with the tremulous ink lines emanating from the artist’s arthritic hands. The relationship between Krazy and Ignatz so close to a metaphor for the marriage of Herriman to his art; the strip like an artistic statement or autobiography, on a lower pedestal than Rembrandt’s numerous self-portraits perhaps but certainly from the same school of ideas.

* * *

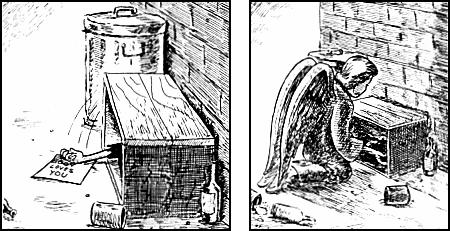

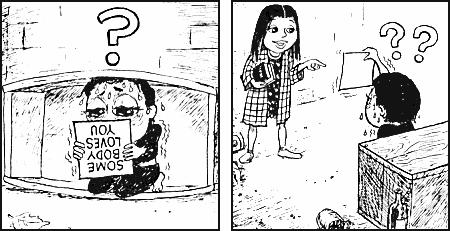

Somebody Loves Me

Those hesitant, shakey lines can bee seen again in Jack T. Chick’s seminal tract, Somebody Loves Me, but here less a product of age and illness than artistic insensibility. This was a best seller by all accounts and one which has been endlessly dissected (or should I say derided) and repudiated. A seemingly impoverished work of cartooning dropped in countless mailboxes all over the world and given to me as a child by a Seven Day Adventist presumably because of Chick’s interest in eschatology.

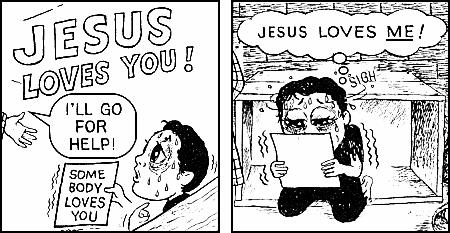

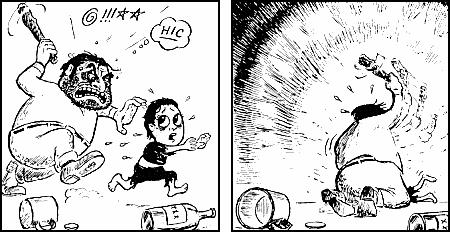

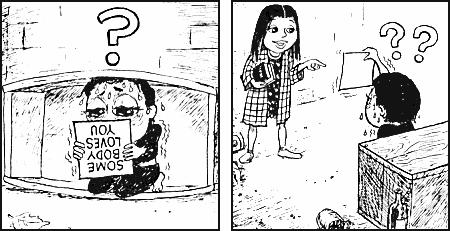

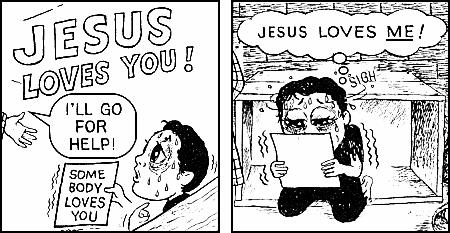

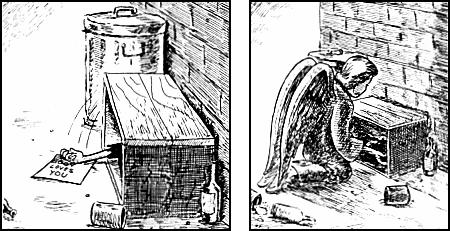

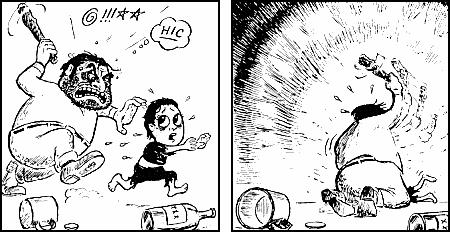

In Chick’s comic, an abused child is viciously beaten by his drunken father before finally withering away in a cardboard box on the streets of a nameless city (some hopeless Sodom or Gomorrah one presumes). But not before hearing the Good News that somebody loves him—”JESUS LOVES YOU!”

The line is untrained, the art of the ultimate outsider cartoonist where others can only pretend to this throne. So despised and rejected, and yet utterly indelible as far as the history of comics is concerned. I don’t know if Chick’s most famous tract ever worked on me but that final image of an angel carrying the abused boy to heaven seems quite grotesque when viewed today.

It is as if Chick had supped on medieval images of the Madonna and child and decided that anti-naturalistic disproportion was fundamental to demonstrating the maturity (or infantilism; it is quite hard to tell) of a newly received Christian soul. This is at odds with a much finer image of an angel kneeling at the box-home of the boy; a drawing filled with the artist’s absolute conviction, that mysterious energy of an outsider determined to promulgate the truth, to communicate by any means possible.

Yet like the works of Richard Wagner—that gross anti-Semite with his apparent caricature of European Jews in the words and actions of Alberich and Mime in Der Ring des Nibelungen—this comic seems impossible to read in isolation. Or so it would appear, for there will always be contrary opinions. The conductor, Daniel Barenboim, who is both a Jew and once led a magnificent Ring cycle at Bayreuth (with Harry Kupfer) recently denied any obvious anti-Semitism in Wagner’s Ring in an interview with Ivan Hewett:

“That’s bull—-,” he snorts. “Do you think I could bear to conduct his music if that were true? Of course there is really vile anti-Semitism in Wagner’s writings, but I can’t accept the idea that characters like Beckmesser and Alberich are Jewish stereotypes in disguise.”

The task with Somebody Loves Me is considerably easier. When Dan Raeburn (writing in The Imp) articulates his vacillation between seeing Chick as either the abused child or the abusing father at the end of his impressive study of the works of Jack T. Chick, he is reappropriating Somebody Loves Me as a metaphor for Chick’s career. For Chick is an artist fascinated with violence (by the Catholics and Jesuits etc.) and pain (the suffering Christ), as well as the forgiving power of a Christian God. One who not only seeks to spread the Gospel (one expects out of dutiful obedience to Mark 16:15-16) but who would also shake the dust off his feet (Matthew 10:14) when faced with those who would reject his message. Hastening the day of the Lord with tough love, those tracts are not merely tools of conversion but also instruments of condemnation to those who would disbelieve.

This mixture of wrath…

…and forgiveness is the thread which links the Old and New Testament and also the entirety of Chick’s oeuvre.

There is nothing inherently offensive about Somebody Loves Me. To see it in aesthetic terms is probably beside the point. One suspects that if but one person had accepted his premise and was sufficiently convinced, it would have satisfied the author. And Raeburn presents us with ample evidence of the tract’s effectiveness (one presumes for good) if largely from the author himself:

“It’s the worst thing Chick has ever done;it’s also as effective as anything he’s ever done. In fact, it’s really well-done. Forget the creation myths—Somebody Loves Me is Chick’s most basic tract, the ur-tract. He’s always had a soft spot for Somebody Loves Me; it’s his favorite of his many little paper babies, sentimentally speaking. For years he’s plugged it with these words: “Hardened men have wept over this tract.” In a 1994 open letter Jack described the first time he showed it to a coworker, a “well-educated and gifted artist,” in aerospace. “Immediately I knew it was a dumb idea,” Jack wrote.“He’ll only laugh.To my shock he burst into tears and told me of his horrible life as a kid….Years later an artist working with us”—and we know who that gifted artist was—“got a call to pick up a homeless girl….He and his wife took her into their home and loved her like a daughter.When they met her she had a copy of Somebody Loves Me clenched in her hand. She had read it over one hundred times.”

What then separates kitsch from true heart rending sentiment or artistic achievement? Is it fully in the eye of the beholder? Is it simply that moment of recognition (of truth)? Or can the answer be found in the imposition of the intellect? Is it even possible to separate the two? Winfried Menninghaus in Walter Benjamin and the Architecture of Modernity offers the following definition of kitsch:

“Kitsch offers instantaneous emotional gratification without intellectual effort, without the requirement of distance, without sublimation. It usually presents no difficulty in interpretation and has absolutely nothing to do with an aesthetics of negativity. It is unadulterated beauty, a simple invitation to wallow in sentiment…”

“Defining kitsch in terms of a saving of intellectual effort and the suspension of normative taboos is rich in implications. For Freud, these behavioral mechanism are typical…, more broadly, of the libidinous regression to infantile gratifications which have normally fallen victim to the reality principle and cultural prohibitions.”

While Chick’s devotion to the true nature of violence defies this definition of kitsch, he embraces it wholeheartedly in the denouement of Somebody Loves Me, an unequivocal statement of intent and mercy. Brushing aside any questions concerning the problem of pain and suffering, Chick’s “ur-tract” is entirely subservient to the final plan of salvation. If we place the Krazy Kat Sunday and Chick’s comic on a weighing scale, there can be little doubt that it is Chick’s comic which shows the most contempt for taboos in its depiction of violence. Yet its ending indulges quite completely in a type of emotional diarrhea (I would say far more than the revered Herriman strip).

Whether Herriman’s cartoon straddles that uneasy place between formal and intellectual rigor, and “instantaneous emotional gratification” I leave to the reader to decide. I should add that Menninghaus further states that unlike other writers of his time, Benjamin “while never fully embracing kitsch, found something not just understandable and admittable in it”, but also “a phenomenon of utmost political significance” and a factor of central concern to art itself:

“Kitsch…is nothing more than art with a 100 percent, absolute and instantaneous availability for consumption. Precisely within the consecrated forms of expression, therefore, kitsch and art stand irreconcilably opposed. But for developing living forms, what matters is that they have within them something stirring, useful, ultimately heartening—that they take “kitsch” dialectically up into themselves, and hence bring themselves near to the masses while yet surmounting the kitsch.”

For me then, Herriman and his creation surmount any would be accusations of kitsch while the Chick comic, despite its florid appeals to realism, wallows in it. For many, that moment when the boy is cradled to heaven would break any illusions of truthful artistry, suggesting the hand of a rampant fool or maniac. For others, that smiling girl offering help in front of the box home clutching a bible would be a moment steeped in delusion and falsity running counter to every experience in their lives.

But those angels are real to Chick and his adherents. His bursting anti-Catholic paranoia and unrelenting bigotry not even sensed here; that spark of creativity and unimaginable artistic acceptance a mere glint in his eye, like an angel’s kiss at twilight.