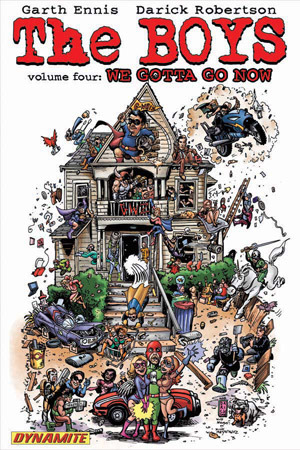

Kate Polak is Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Wittenberg University, and she does research on violence and sexual violence in comics, especially Vertigo titles. We met through the Comix Scholars list serve, and Kate agreed to have a conversation about violence and comics for HU. We decided to focus on Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson’s comic The Boys, specifically the volume We Gotta Go Now.

Noah: So…I guess maybe we could start by talking a little about that review by Francesca Lewis about the Boys. Basically she’s arguing that its violence and sexual violence is part of satire, right? She argues that he’s mocking comics by showing the violence and brutality and sex that isn’t present in typical comics for kids:

“The extremity and excess for which he is often criticised is a direct contrast to the empty, one dimensional world of comics. He includes every violent, sexual and controversial subject that is present in the real world and conspicuously not present in classic comics. “

You said you had some sympathy for that view. Do you think she’s right, or that Ennis is parodying comics by making The Boys more realistic?

Kate: I think she’s certainly right..to an extent. In the first place, I’d be remiss if I didn’t critique her homogenization of feminist critics and literary scholars. She really does a terrible disservice to feminism as a concept in that article. “Rawr! Feminists think this, but I think that.”

My sympathy with her viewpoint is rooted in a long, complicated personal history with Ennis, who I have loved for many years, but am growing increasingly less fond of with every subsequent issue of Crossed.

Most of the sexual violence he’s used in previous works, Preacher and Hellblazer being only two examples, bears critique, but also critiques itself. In Hellblazer, he has Constantine’s ex-girlfriend get raped by a jealous ex. When he comes to try to “help”, the female friends (including his own girlfriend), tell him to get out of the hospital room. What I always liked about his portrayals was how aware he was of the power dynamic between women and men, and how he allowed women to have some power even in moments of extreme victimization.

As to The Boys, the extremity of the work, I think, does an excellent job of parodying superhero morality, while at the same time, shamelessly indulging in some horrifying stereotypes as well. Who is our superheroine? Well, she’s blonde and white, and a former Christian. Who’s our hero among The Boys? Wee Hughie, a weird sort of nice-guy-nerd-fantasy that, to me, is a transparent appeal to nerd, verging on MRA readership.

Noah: I guess to me at this point in the superhero genre, I’m just somewhat skeptical of the baseline assumption that superheroes don’t deal regularly with issues of violence and sexual violence. William Marston and Harry Peter actually deal pretty directly, and I think sensitively with sexual violence in their Wonder Woman run from the 40s (Link here). That’s a bit unusual, but good girl art and fairly up front prurience was present in superhero comics from the beginning. There’s a lot of violence in those early comics too…people being murdered in horrible ways by the Joker, for example. And certainly by the time you get to Watchmen in the 80s, you’ve got lots of folks writing about the links between supeheroes and sex and violence, in thoughtful and less thoughtful ways. It’s just hard for me to see The Boys as parodying or undermining tropes when it seems in line with so much else that’s being done. Like, is a supehero pedophile ring really different in kind than superheroes teaming up to brainwash a villain, causing intense psychological trauma (which has happened in DC continuity)? Or the Joker shooting Barbara Gordon in the stomach and then showing her naked pictures to her dad? Or the current Wonder Woman continuity where we learn that the Amazons are not avatars of peace, but are instead rapists and child killers? Not that adult material always has to be bad necessarily or in every instance, but it’s hard for me to see how The Boys gets seen as parodying or commenting on the hypocrisy of mainstream superhero comics when as far as I can tell it’s indistinguishable from them.

Kate: I don’t know. I see the institutionalized rape of children as a pretty extreme, and topical phenomenon. That couldn’t have been anything *but* a swipe at the Catholic Church, right?

In terms of parody, I don’t really see parody as an all-or-nothing game–most works contain elements of their own critique, as well as a critique of the social sphere they’re mimicking. Furthermore, I see parody as simply a (perhaps) more extreme, but certainly more self-aware indulgence in the exact same phenomenon as the things that already occur in the genre in question. Parody isn’t turning a genre on its head–its exposing the ludicrous elements of a genre that already exist.

And that’s why I’m going to keep loving Ennis, even if I can’t always love him, and if I sometimes hate him. There are so many hints as to how he’s aware of how much uglier he’s making already-existing tropes, down to the art. They always pair him with hyper-realists, like Dillon and, in the case of The Boys, Robertson and Higgins. That style is commonly associated with adventure comics from the colonial and immediately post-colonial eras, wherein we, as readers, “discover” “darkest Africa.” I think the artwork does a good job of pointing towards the parodic tendency as well, as it did in Watchmen.

I suppose what I’m saying is that I find The Boys valuable because it goes out of its way to expose how common these elements are, and stretches them to their (possible?) limits. It’s not that sexual violence and other types of extreme violence don’t take place in comics that came before–it’s that the violence does, but the artists and writers often don’t seem to be aware of its absurdity. Or perhaps that they fail to recognize its regularity.

Or, and this is where I do most of my work, it’s that it exposes (through parody) the absolute saturation in culture of sexual violence.

Noah: I think superhero parody is a longstanding and central part of the superhero genre; everything from Plastic Man to Wonder Woman to Watchmen to the Spirit can be seen as parody, really; parodies are just really central to the genre.

So for me it’s not really whether it’s parody or not, and more whether what it’s doing is particularly interesting. And I have to admit, I’ve got problems finding much of interest in the Boys, or at least in the “We Gotta Go Now” story arc. I’d say, yes, the pedophile ring is referencing the Catholic Church…but I don’t really see it as being particularly thoughtful about that link, nor as having much of especial interest to say about it. In terms of exposing a culture of sexual violence — it just seems like it’s reproducing that culture to me.

Not just in terms of the fact that it shows sexual violence, but in the way that sexual violence is supposed to be validating for the comic, right? That is, the comic is engaged on revealing the secret truth of the perverted nature of superhero comics, and it does that by revealing what’s in the closet, that being sexual secrets and sexual violence. The brutality and violence show that the comic is a serious adult work.

Watchmen arguably does something similar — but I think it makes much more effort to question whether sexual violence is truth, or whether violence is. I don’t see any of that in the Boys, really. The truth just leads to greater redemptive violence, and then at the end to the abused kids getting murdered, so that you know the good guys aren’t good. It’s reversal after reversal, the truth revealed always being that people are awful and sexual violence is brutal, and isn’t it cool we’re reading this adult book?

Kate: Hehe. I like your reading. That’s where I think Ennis goes off the rails sometimes, although, specifically in We Gotta Go Now, I think it hews to a cyclical violence in which victims become predators and breed more victims, which is an area that comics has–I think–not been good about exploring.

Mostly, I would argue, the superhero genre likes its victims as victims alone, and not as more complicated creatures. It’s not in this issue, but in The Boys, Annie January is a victim of sexual coercion/violence, but she’s allowed to still have an active and positive sex life after her victimization.

In terms of the victims, I think that the comic shows a good deal of the nuance in the characters, as well as their level of psychological damage. Silver Kincaid kills herself in a particularly awful way. G-Wiz are socially ill-equipped to deal with society and have no boundaries, but we nonetheless feel real sympathy for them (at least I did). Godolkin might as well have been reciting a NAMBLA message, but we see the material consequences of his actions.

I think it’s important to remember who does the violence in We Gotta Go Now: it’s a corporate entity with a financial stake, rather than a personal stake, in the abused children-turned-predators. The government entities–The Boys–are willing to fight them, but it’s the corporation who comes in with the flamethrowers (and I use “who” advisedly, given recent Supreme Court decisions).

Most of The Boys lies in those reversals, too–as the storyline plays out, we’re increasingly made aware of the fact that Butcher is as bad as the bad people, and some of the supes aren’t that bad–some are good, and, if not for complicating factors, others could have been better.

So, what keeps me a fan of The Boys are those reversals, and the refusal to allow anyone to go uncompromised. In Watchmen, Laurie and Dan are pretty much good people. Wee Hughie is the closest we have in The Boys, and even he has his moments of homophobia (which is mocked), misogyny (which almost costs him love), and sheer ignorance.

As to prevalence, that’s one of the things I like about the annihilation at the end of We Gotta Go Now. No redemption for you.

Noah: Well, I haven’t read the whole thing, obviously.

I don’t actually think it’s true that superhero genre likes its victims as victims though, exactly. Superheroes themselves are almost all victims of trauma right? Batman, Spiderman, Hulk; it’s all about initiating trauma leading to vengeance or heroism.

Laurie and Dan are good people; they’re in a romance plot — though they’re also not exactly normal, and certainly have their own oddities. I think that having a real romance plot is actually a lot more of a challenge to superhero genre conventions than having evil corporations kill people. Violence as a solution, in whatever form, isn’t really a challenge to superhero logic, I don’t think. The happily ever after romance ending, the idea that solutions or happily ever after, is achieved without violence is a good bit more of a pushback against how supehero comics work…or so it seems to me, anyway.

What do you think about the fact that the two characters who break down on the pedophile team are women, and that the group of teen up an coming characters we’re supposed to sympathize with are coincidentally all guys?

Oh…and I really didn’t find that teen group especially sympathetic. They seemed like out of control frat assholes. Wee Hughie kept saying he liked them, and I kept thinking, good lord, why?

Kate: I think it’s unsurprising, given how we socialize men and women. I’d like to say “we can allot space for men to have feelings”, but we don’t–Jamal crying at the end was, to me, a real moment. A man admitting he was a victim of sexual violence and crying about it? Whoa.

The fact that men aren’t allowed to show these emotions is, I would argue, one of the things that leads to greater perpetuation of violence. It gets sublimated into an action on an other. “I’m not powerless. Look at what I can do.” And I think Ennis, through Jamal and others, is trying to expose that for what it is.

But I think that’s also where we’re sliding past one another in the debate. I can’t possibly think of Batman, Spider-Man, and the Hulk’s traumas as being similar to sexual violence, especially sexual violence inflicted on kids.

Remember, sexual violence is the *only* form of violence in which something that’s supposed to be pleasurable is turned against the victim. No one, aside from a subset of the BDSM crowd, legitimately enjoys getting punched in the face. No one orgasms from it. No one enjoys their parents dying. No one enjoys being picked on. Those are non-equivalent forms of trauma.

I sympathize with not liking them. To me, they looked very familiar. Relatively normal dudes on a college campus, with (many) fewer boundaries. And I sympathize with my male students, who are trying to figure out how to have fun, how to be men, and how to treat women, when they’re given terrible messages about all three.

Noah: I mean, Jamal is sympathetic at the end. But he’s hardly even a person before that, is he? I don’t really see any effort to make any of those guys people, pretty much; they’re not individuals. I barely learned their names. They just come across as a mass. I don’t get much sense that Ennis gives a crap about them as individuals, either. He certainly doesn’t bother to give them individual personalities.

You know that in some versions of continuity Bruce Banner is in fact a victim of child abuse, right? I don’t think it’s at all a leap to see the Hulk as a symbol of a traumatized child. Batman is explicitly the victim of massive childhood trauma. There are definitely things going on with Spider-Man that suggest possible sexual trauma — Craig Fischer has a fascinating essay about Ditko’s use of hands in his work, and I think it’s possible to read a subtext around sexual violence there, and link it to Spider-Man’s particular anxieties about manhood and power.

I think separating out sexual trauma as completely different from other forms of trauma…I don’t know. Kids who are hit by their parents also have issues around betrayal of trust and love. I mean, children do wish for their parents to die; sexual fantasies and pleasures aren’t the only kinds of pleasures. Any trauma is non-equivalent to any other form of trauma, but that doesn’t mean that there are no parallels.

I agree with you that misogyny and the fact that sexual trauma is supposed to be an attack on men’s masculinity is a pretty horrible thing for everyone, and a way that such violence gets hidden and perpetuated. I’m just skeptical that Ennis is dealing with that in a particular intelligent or thoughtful way. His victims of sexual violence here are basically completely out of control, and their trauma is basically used as an awful secret and then an excuse for violence, not as a way to actually explore their stories in any particular extended or thoughtful way.

I just read Gwyneth Jones’ novel Bold As Love, coincidentally, where there is also an abused child who goes on to abuse children himself. He’s only in the book off to the side, really, and I wouldn’t say he’s exactly sympathetic, but there’s just a lot more sympathy for him I feel like — partially because we see him through the eyes of another character who is also the victim of sexual abuse. She’s not completely broken though (and in many ways not broken at all), which creates some space in the book for sexual abuse to not be the one true thing about its victims, male or female. I don’t see a lot of that in Ennis’ story.

Kate: I didn’t know that about Peter Parker, although it’s an interesting interpretation! I’d love to read that article.

Yes, sexual pleasure isn’t the only pleasure, but I still see sexual abuse as substantively different from other types of abuse. Not “more,” but certainly different. While I think you’re right to say that there are parallels, I think that we often overplay the parallels in studies of violence in general, which in itself serves many of the rape myths that have been made at least a little more apparent by the recent focus on sexual violence (in your work, among others). I still see a pretty big gulf between reactions to a rape victim and a mugging victim (or, more appropriately, a maiming victim), and those reactions are based in part on our own experiences of sex versus violence, as opposed to sexual violence, which is another creature entirely.

Seeing your parents murdered is undoubtedly immensely traumatic. I’m still reluctant to map it onto the experience of sexual violence, though, because *seeing* is different from the violation of the bodily envelope, no matter how you slice it, and when the body is violated in ways that are supposed to be reserved for pleasure, there’s an enormous further gap between a rape, and, say, a stabbing.

As to Ennis, I’m certainly approaching it differently than you, but what I see is a lot of scared little kids with stunted personalities who grew up to have immense power–not unlike a lot of violent offenders today. In terms of individuality, I don’t think he cares enough to give them major individual attention, because they’re implicated in crimes as well, whether or not those crimes occurred “because they had a troubled childhood.”

I should note that, when I say I sympathize, that isn’t equivalent to saying “I understand” or “I could see myself in that position.” I see it more as a commentary on the extent to which that behavior is familiar and legible within a broader cultural framework.

You compared them to frat boys. Frat boys, and rapists, are also *people*. But that doesn’t mean we have to have an overweening sense of their individuality. I see The Boys in some ways as a nice corrective to the post-WWII obsession with the “complicated minds” of perpetrators.

Oh, and as to “the one true thing”–I don’t know. I think it’s alright to acknowledge that sexual violence can fundamentally and permanently alter the way someone relates to the world. It doesn’t need to make them into a permanent victim, but in the case of Annie January, it completely changes her approach to life, and that’s simply treated as a fact–not a “good” or an “ill”. The act itself was bad, but the way she deals with it simply stands as a way of living.

Noah: I didn’t say they weren’t people or that they should be killed. I just don’t really see why we’re supposed to like them more than the older superheroes (who are also people, or representations of people, right?)

I’d certainly say that we treat sexual violence differently in a lot of ways. But isn’t the idea that there’s some sort of innate difference in kind between violence and sexual violence — can’t that be seen as perpetuating the difference in some ways? I guess the truth is I don’t know enough about the relevant literature here, but it’s at least my impression that different kinds of trauma can result in pretty similar effects — disassociation, PTSD, flashbacks, and the like.

I’m not looking for complicated minds. I’m looking for some reason to be able to tell them apart, pretty much at all. Or some reason that Hughie likes them. It’s certainly reasonable to think that that kind of trauma has an intense and longstanding effect on people. But that’s a bit different than having characters who are pretty much completely defined by their victimization, as the group in We Gotta Go Now seems to be. It sounds like he does better with Annie January elsewhere, but in this case it’s hard for me not to see it as just exploitive and shocking for its own sake, mostly.

Maybe it’d be different if I’d read the whole series, I don’t know. I didn’t much care about any of the characters, honestly. They could have all died at the end and I would have pretty much just shrugged.

Kate: I’m going to take the last point first, then get into the sexual trauma v. other trauma. As to the series, I’m not saying it doesn’t have its flaws, and I imagine readers would have a range of reactions. I’m arguing for it because I saw a number of interesting spaces for discussion, including “what is the point of representing a corporation with an infrastructural investment in the abduction and abuse of children, so as to invest them with powers they don’t know how to control and to render them permanently infantalized?”

I’d even go so far as to bring in IMF and World Bank policies into the discussion, but I don’t know if I have the juice left in me tonight.

I’ll content myself with saying The Boys represents a nexus between extreme sexual violence, extreme violence, sexuality, celebrity culture, corporate greed, corporate and government collusion, global terror, and war that captures an interesting slice of what living in the post-9/11 media landscape is.

As to sexual violence versus violence, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with perpetuating the difference. There is a difference, and it’s a big difference. Yes, it *can* have the same effects (although not all people who see combat are traumatized, and similarly not all rape victims are traumatized). PTSD is a collection of symptoms–the originary trauma doesn’t matter in terms of content in a PTSD diagnosis. However, and this is a big however, defining sexual violence only in terms of the trauma in victims misses a lot of the point. Most women–around 50-70% in various studies–show signs of PTSD regardless of whether or not they’ve been victims of sexual violence. Those who haven’t tend to exhibit mainly hyperarousal–waiting for a threat that may or may not come.

As to the differences in actual experience, a symptom profile doesn’t exactly map on to an experience. One of the biggest complaints about the second-wave tagline of rape being about power rather than sex were rape victims asking “then why didn’t he just hit me? I would have preferred that.”

Noah: Yeah; I wouldn’t want to claim that rape has nothing to do with sex. But that doesn’t necessarily mean either that rape is the worst violence or the most traumatic violence in every situation, right? In terms of something like Susan Brownmiller’s discussion of rape in wartime, the analysis suggests less that rape isn’t about sex than it suggests that war and violence in general are pretty closely connected to sex in ways that we don’t really like to acknowledge.

In terms of the IMF and World Bank…I see the metaphor, but also kind of wonder if representing non-Western peoples as abused children who don’t know how to deal with their powers is necessarily a helpful or insightful way to think about these issues.

Kate: Oh, totally, but Ennis is an unrepentant Anglophile, which is something worth exploring, especially given the fact that few comics ever deal with the Global South at all. Notable exception: Unknown Soldier, which is not a very strong work, but at least takes place in Africa and has African characters.

In terms of violence vs. sexual violence: like I said, not “more,” just “different.” I think the connection is certainly there, but I can’t say I entirely agree with Brownmiller (or, say MacKinnon, who argued that “porn is the theory and rape is the practice”). In part, it goes to the question of “sameness” versus “difference” feminism, and they’re both polemics. I don’t have to choose one in order to say that rape is a substantively different experience from other forms of violence. I know it’s different. And there’s, to be frank, a lot more emotional nuance in rape than there is in other forms of violence, including domestic violence. Most rapes are acquaintance/date rapes, much like the molestation we saw in The Boys. There’s a lot of subtle manipulation, rather than out-and-out violence. It’s easier to hate your attacker when they inflict something that clearly counts as violence, but what does it mean when your attacker convinces you that their act is an act of love?