Here’s the debate question we need to ask Clinton, Trump, Sanders, and the herd of Republicans running for President:

“What art would you hang in the Oval Office?”

It sounds frivolous, but the answers reveal a lot about our last two presidents.

When George W. Bush moved from the Texas governor’s office to the Oval Office in 2001, he brought his favorite painting, a 28 x 40 oil by Westerns illustrator W.H.D. Koerner which appeared on the back of his campaign biography, A Charge to Keep. The title is from a hymn, and a friend gave him the painting because it illustrated a 1918 short story of the same name. Bush believed the figure in the painting, a cowboy charging up a hill on horseback, was a 19th century Methodist evangelist spreading his faith across the West.

“He’s a determined horseman,” the President told visitors, “a very difficult trail. And you know at least two people are following him, and maybe a thousand.”

“Bush’s personal identification with the painting,” writes David Gergen, “reveals a good deal about his sense of himself . . . . a brave, daring leader riding fearlessly into the unknown, striking out against unseen enemies, pulling his team behind him, seeking, in the words of Wesley’s hymn, ‘to do my Master’s will.’”

Although the painting did appear beside Ben Ames Williams’ “A Charge to Keep” in Country Gentleman Magazine, Koerner painted it three years earlier for The Saturday Evening Post to illustrate a story by William J. Neidig called “The Slipper Tongue.”

The horseman is a horse-thief fleeing a lynch mob.

But whatever its title, the work has become the best known of Koerner’s over 800 commissioned paintings and drawings, including “Hugo Hercules,” the original comic strip superhero.

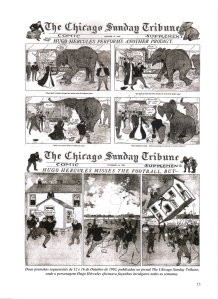

Koerner immigrated from Germany at the age of three, and seventeen years later got a job as a staff artist for the Chicago Tribune for $5 a day. His duties included producing a Sunday strip for the Comics Supplement. He came up with an urban cowboy with super-strength. If that’s not enough to call him a superhero, Hugo calls himself “the boy wonder” while aiding a series of Chicago damsels-in-mild-distress.

He has his own catch phrase too, “Just as easy,” tossed off whenever he performs some inhuman feat, like ice skating with a boat on his shoulders or flinging a defensive line of football players across a goal post. Sometimes he adds, “I could do this forever,” as if Koerner hasn’t drawn him in a sufficiently effortless pose. Clark Kent wouldn’t declare, “This is a job for . . . Superman!”for almost four decades, but Hugo knows when “It’s up to me!”

Oval Office visitors commented how Koerner’s Methodist horse-thief looked a bit like George W., but Hugo was the one with the cowboy hat—offset by a sports jacket, stripped pants and bowtie. The hat vacillated between white and black though, and Hugo vacillated too. Overall he was a force for good, but his altruism was random and occasionally the good he did was correcting the harm he’d done—like when he missed a football and accidentally punted a house across a field. But at least he lugged it back, right? And so what if he uses his strength to collect the bowling competition prize money after destroying a wall and passing trolley in the process? After catching a falling safe from crushing an old man as his daughter helplessly watched, he asks: “Am I glad I did it? Wid de doll’s arms around me neck and de old gent coffing a three spot? Am I glad?”

Note that folksy way of talking too. No wonder George W. liked Koerner. And if Hugo can be a bit destructive—did he really have to rip up a porch to carry it umbrella-like over a woman worried about the rain?—he helps far more than he harms, like when he catches that family jumping from a burning house, or when he carries a fire engine to another would-be disaster. He stops that runaway horse before it crashes its owner’s carriage, but more often he only saves damsels from mild inconvenience, halting trolleys and cable cars that refuse to stop, or lifting an elephant standing on a handkerchief. And how did the striking cab-driver’s union feel when he carried that woman and her pile of crates? Dragging a derailed train twenty miles is nice, but is lifting a young Romeo and his car to his Juliet’s balcony for a parting kiss really the best use of one’s superpowers? As far as actual menaces, Hugo does wrestle a bear into submission—though he was only saving himself. Same with those three muggers who corner him at gunpoint. They look ready to abandon the criminal life after he points a canon in their faces.

Would their bullets have bounced off him? Could he have leapt tall buildings if they’d tried to escape? No idea. We’ll never know how Hugo might have matured into his yet-to-be-named genre. The strip only ran from September 1902 to January before Koerner abandoned it for better work. Soon he was studying with famed illustrator Howard Pyle, creator of the 1883 classic The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, as well as varied adventures of Arthurian knights, noble pirates, and a modern Aladdin. It was a thorough education in proto-superheroes, but Koerner’s interests turned west when The Saturday Evening Post commissioned his first two frontier scenes instead. He never returned. When he died at the age of 58, he was one of the best known artists of the Old West. That was 1938, the year Action Comics No. 1 rode onto newsstands.

When the Bushes returned to Texas, they took their so-called “A Charge to Keep” with them. The Obamas, fresh from Koerner’s hometown of Chicago, replaced his galloping horse-thief with a more traditional Saturday Evening Post illustration, Norman Rockwell’s “Working on the Statue of Liberty.” At 24 x14, it’s less than half the size of Koerner’s work. It depicts four tiny workmen scaling the torch to clean its amber glass. It’s slow, dangerous work—something Hugo Hercules could have finished in three panels.

The Obama Oval Office, however, is not cowboy-free. Frederic Remington’s sculpture “The Bronco Buster” still sits on its side table, and the President not only kept but expanded his predecessor’s spy programs, herding up emails across the frontier of the World Wide Web. When German Chancellor Angela Merkel found out the NSA was following their Master’s will and bugging her phone, her government threatened the diplomatic equivalent of a lynch mob–counterespionage. “They’re like cowboys,” explained a party member, “who only understand the language of the Wild West.”

What language will our next President understand?