This is the second part of my discussion of Italian giallo films. The first part can be found here.

_______________________

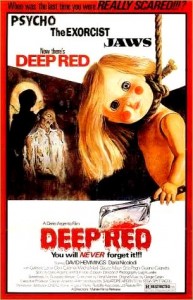

Deep Red a.k.a. Profondo Rosso (1975)

Directed by Dario Argento

Movie reviews usually begin with a summary of the plot. Which is a problem in this case, because the plot of Deep Red makes no fucking sense. It begins in Rome at a conference sponsored by the European Congress on Parapsychology. It may sound far-fetched, but it’s every bit as scientific as phrenology or evolutionary psychology. The marquee attraction is a German psychic named Helga Ulmann (Macha Meril) who entertains the crowd by reading their minds. But someone in the crowd is a murderer, and Helga stupidly announces this to the audience even though she fails to identify the killer. And so the killer tracks Helga home and chops her but good with a cleaver.

The first person to discover the body is English pianist Marcus Daly (David Hemmings). Marcus decides to solve the murder all on his own because he apparently has nothing better to do, and pianists are naturally gifted as criminal investigators (and since this is a giallo, the police are worse than useless). Marcus is helped by a reporter, Gianna (Daria Nicolodi), but is warned to drop the matter by his friend Carlo (Gabriele Lavia). Marcus enlists the aid of a parapsychologist, Dr. Giordani (Glauco Mauri), and uncovers a clue to the killer’s identity by reading a book on urban legends. The book conveniently (and implausibly) identifies a house once owned by the killer, which leads to several more fortuitous discoveries, eventually revealing that the killer is none other than Carlo’s crazy-ass mother, Martha (Clara Calamai). Back when Carlo was a little boy, Martha murdered her husband when he threatened to send her to an asylum. Martha tries to cover her tracks, first by killing Helga, then by stalking Marcus and killing everyone that he drags into his investigation, including the author of the urban legends book and Dr. Giordani.

If I were to judge the film on its merits as a mystery, it would be a failure. No amount of gore can cover up a preposterous plot and mediocre acting. And yet I liked this movie.

About two-thirds of the way into the story, Carlo attempts to kill Marcus so his mother’s actions will never come to light. Carlo even accuses Marcus of being responsible for all the deaths. If only he had minded his own business, no one except the psychic would have died. It sounds like the standard villain monologue, blame the hero for everything, etc., etc. … except everything Carlo says is true. Martha is crazy, but she only killed to hide her identity and cover up the earlier murder of her husband. Psychic Helga was doomed, but Martha killed the other victims only after Marcus got them involved with his amateur sleuthing. Is the viewer supposed to agree with Carlo and condemn Marcus? Not likely. Carlo suffers his own violent death just a few minutes later, which illustrates the primary appeal of the film. Marcus is an idiot, but he’s an idiot who moves the plot forward. And the plot provides a simple framework for the death scenes.

While the entire film is visually attractive, the death scenes are labors of love by Argento. They’re gratuitous, elaborately staged, and almost dream-like. When Dr. Giordani is killed, he isn’t just stabbed. There’s a robotic (?) puppet charging at him, and a shot from the killer’s POV as she grabs Giordani, and a close up of his mouth being jammed into several sharp corners, then a close up shot of the gleaming knife that tracks it’s motion, followed by the actual stabbing. And this mayhem is accompanied by a funky rock soundtrack courtesy of Goblin. Carlo’s death scene is even crazier. While escaping from the police he wanders into the street just as a garbage truck approaches. Any other director would simply have the truck hit Carlo, but Argento allows Carlo to barely evade being hit only to get caught by a hook that for reasons unknown is hanging from the back of the truck. So poor Carlo is dragged through the streets, and the truck makes every turn as sharply as possible so that Carlo will careen into the curb. His physical destruction is capped by a car running over his head.

The death scenes feel disconnected from the slow-paced mystery that contains them, as if a completely different movie takes over when the point-of-view shifts from Marcus to Martha.* But then Marcus is a drearily sane character who inhabits a sub-par crime thriller, while Martha is this delightfully insane monster who thinks she’s in a slasher film. Marcus lives in a world of clues and motives, Martha lives in a world where the violence is obsessive, unlimited, and always viewed from the best angle. Her blood is too red to be real, but who cares? It’s better than real.

Friday the 13th, Prom Night, Terror Train, Scream – countless slasher films have followed in Deep Red’s trail, combining the violence of grindhouse horror with the “whodunnit” mystery plot. And like Deep Red, most slasher films fail as mysteries. The first Friday the 13th, for example, resembles a giallo murder mystery, including shooting the murders from the killer’s POV to hide her identity. but the film doesn’t even introduce the villain until the final act, and since all the other characters (minus the heroine) are dead by that point, there’s no mystery as to who the killer is. Even the half-way clever Terror Train, which at least has a red herring or two, suffers in comparison to traditional mysteries such as Murder on the Orient Express.

It shouldn’t be impossible to produce a decent mystery that also happens to have gory deaths, but why would a mystery writer bother with extreme violence? It adds nothing to the plot and more than likely will become a distraction. And from a commercial perspective, it will almost certainly drive away a portion of the target audience. In contrast, slasher filmmakers lack the subtlety and restraint that mystery requires. The adolescent love of gore, a desire to scare the audience (or at least startle them), and an inexperience with the mystery genre collectively produce barely coherent plots that string together a few gruesome murders.

But in the hands of Argento, at least those murders will look good.

.

_________________________

* Carlo’s death scene is the one exception, because no other character is present to observe his demise.