By now, everyone knows that Grant Morrison is taking on the role of Editor in Chief for Heavy Metal magazine. As someone who is three years into a complete reread of the entire run of the publication, this is of great interest to me.

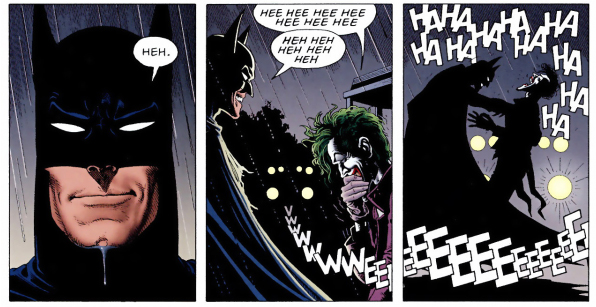

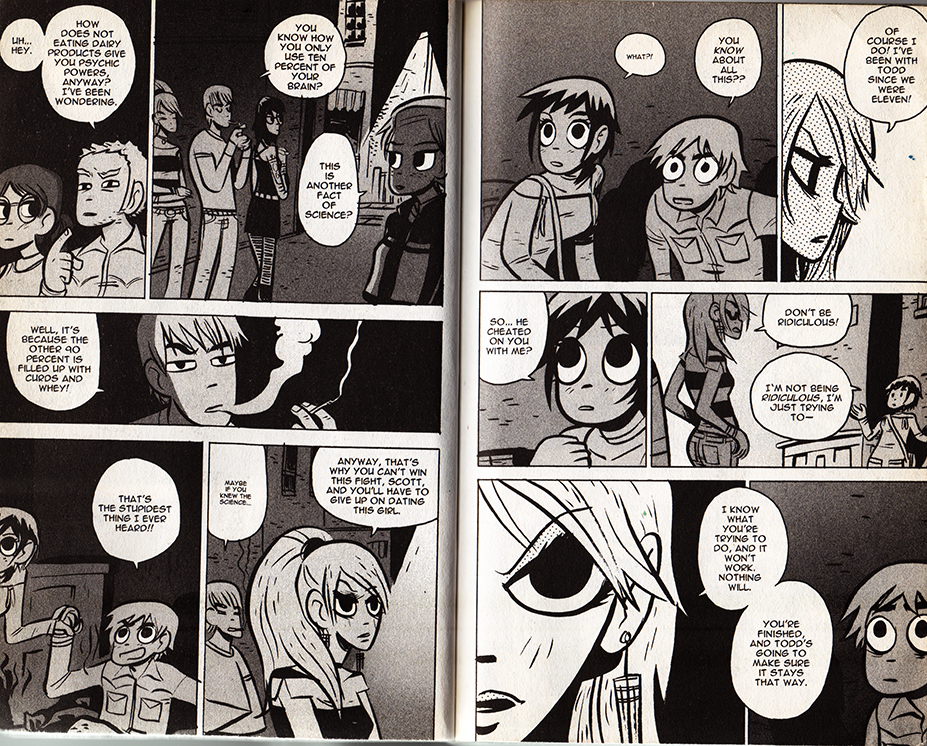

My first reaction to this announcement was “again?” I’ve seen this kind of stunt casting for Editors before. When I read Grant Morrison’s comment that “[w]e’re trying to bring back some of that 70s punk energy of Heavy Metal,” I had to wonder if he actually, y’know, read the magazine during the 70s and 80s. Of all the labels that could possibly be laid at the feet of Heavy Metal during that period, punk is the only one I wouldn’t use.

First of all, the magazine was originally published by National Lampoon, a not-inconsiderably-sized company that released movies (Animal House, Vacation) and sold an awful lot of branded merchandise during the 70s and 80s. The pages of early Heavy Metal were packed full of advertisements for National Lampoon stuff. None of that really came across as punk to me at all. As Heavy Metal went on, they became much more obviously commercial, with their own brand of merchandise that was advertised in every issue.

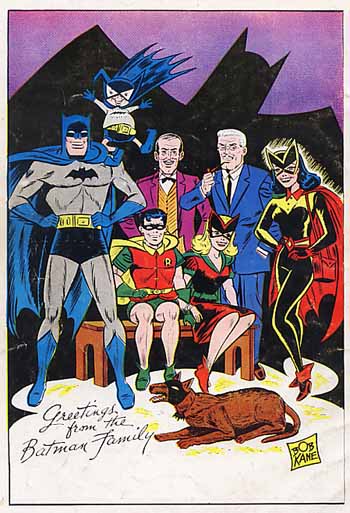

An ad for Animal House from an early issue of Heavy Metal.

Second, a lot of the early material is very psychedelic and appealed mostly to the aging hippy demographic, which was, if I remember Sid and Nancy correctly, directly antithetical to the ethos of punk. Furthermore, Ted White was a big prog-rock fan and the material that was produced under his guidance leaned very heavily in that direction. If you were an Ultravox fan, Heavy Metal in the early 80s was absolutely the magazine for you.

An ad for a Ted Nugent album, from March of 1979. Tres punk.

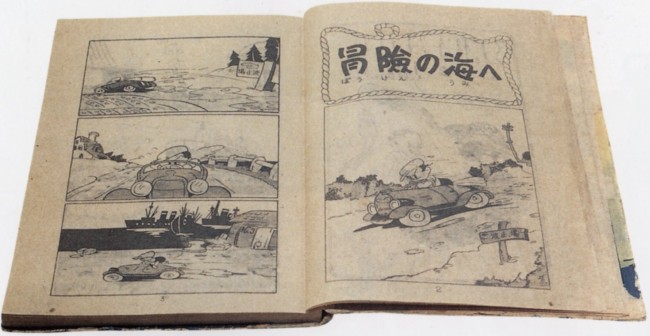

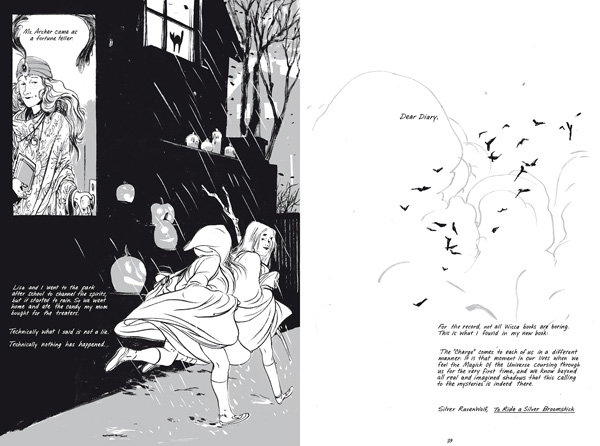

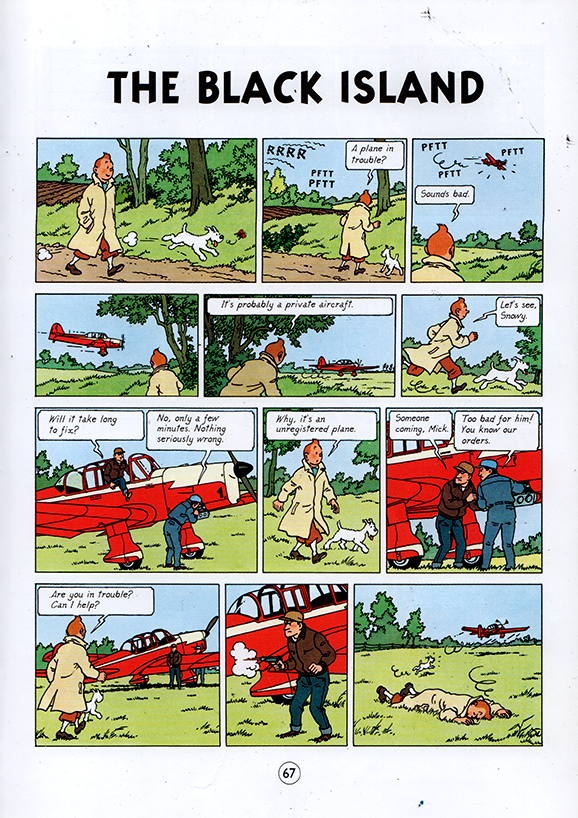

Third, the revolution that really drove Heavy Metal was very distinctly French and had a lot more to do with the format of how French comics were serialized than with any kind of musical aesthetic, something that is largely transparent to Anglophones. Instead of serializing stories 22 pages at a time on a monthly basis, French BD magazines serialize their stories half a page at a time in weekly anthologies and have done since the 50s. It was a technique made popular with Tintin magazine, and perfected by Spirou. By the end of the 60s, Pilote (under the editorial guidance of Rene Goscinny, not coincidentally, the writer of Asterix) was the big boy on the block, largely due to this production methodology.

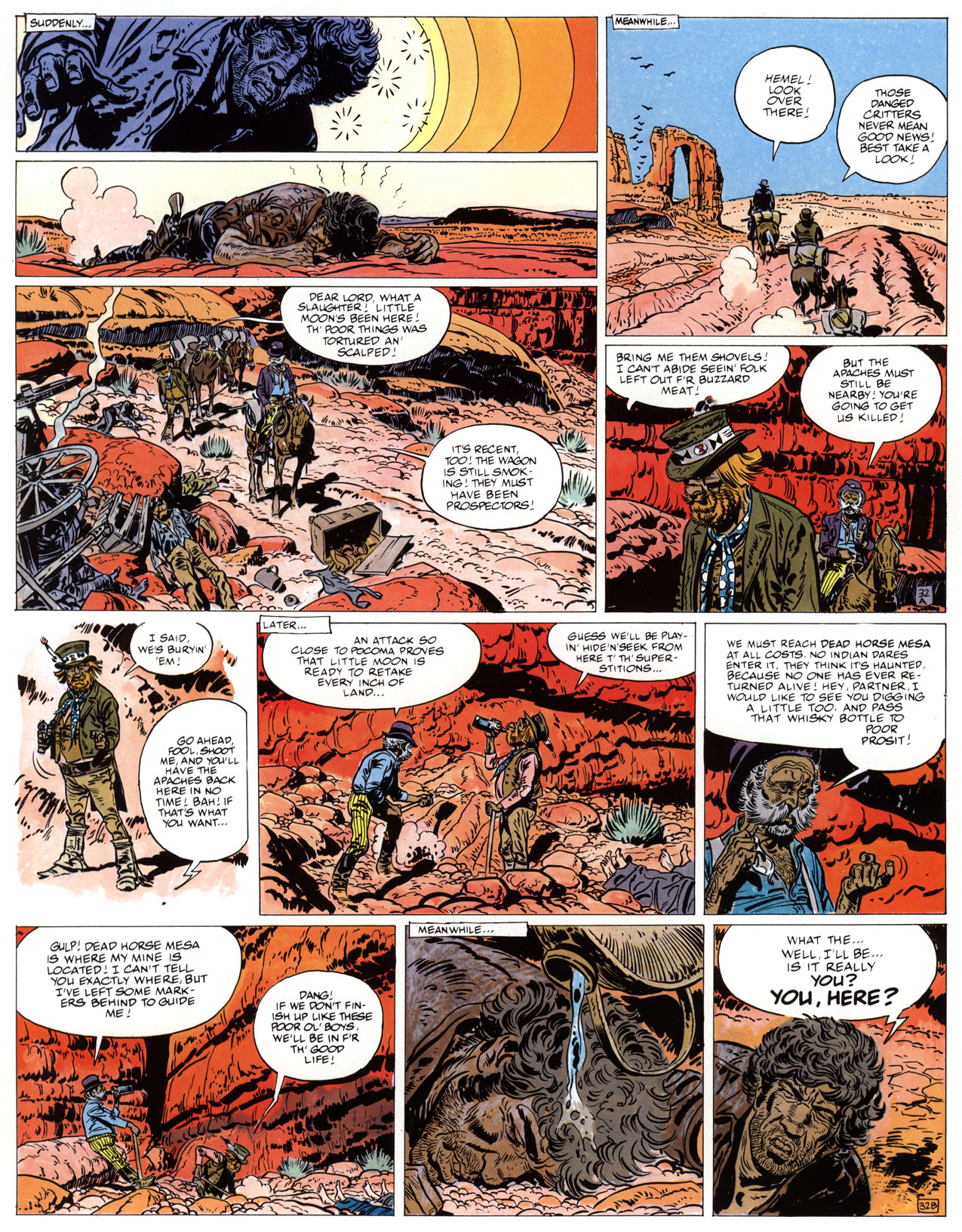

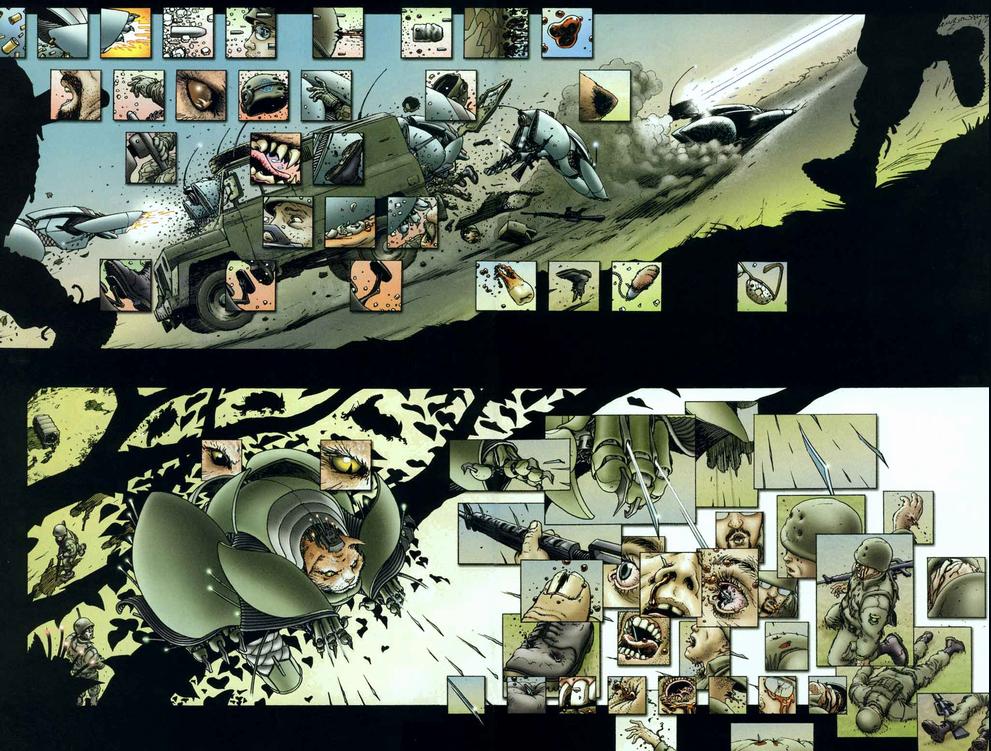

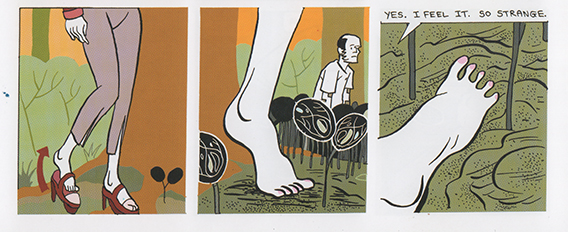

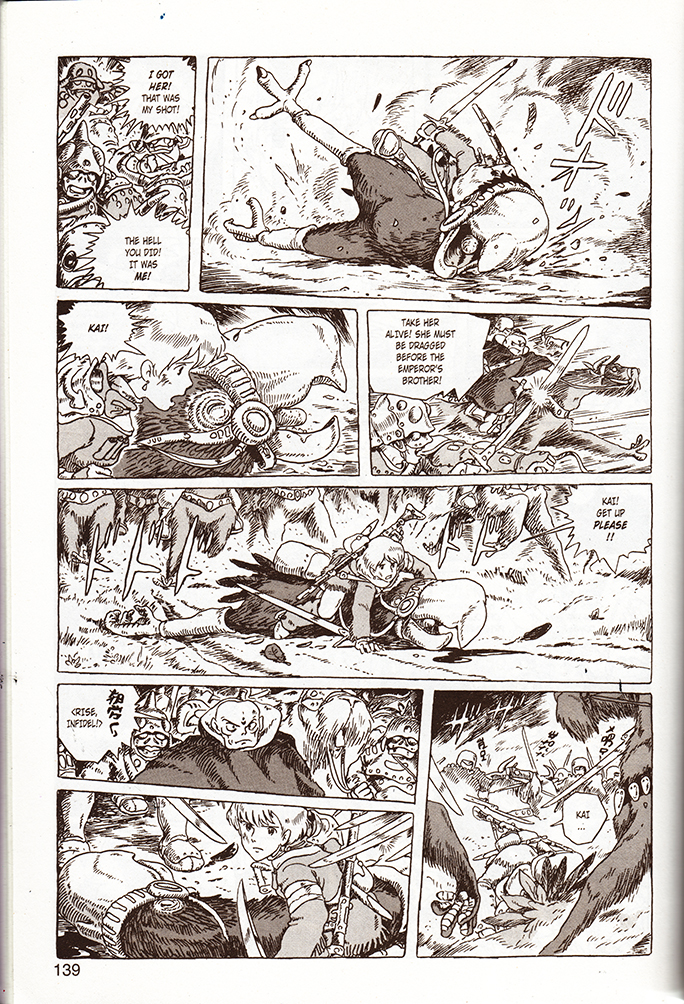

The collected editions of popular stories and characters would stack half-pages together to create magazine-sized albums. Take a look at any French (or European) BD collection produced before 1970 – Asterix, Valerian, Corto Maltese, Blueberry, Philemon, Spirou – and you will notice a white gutter running horizontally through the middle of almost every page in the book. This is a direct artifact of the serialization methodology, regardless of whether the story was actually serialized or not. There were occasional splash pages in these books, but that’s more of an exception than a rule.

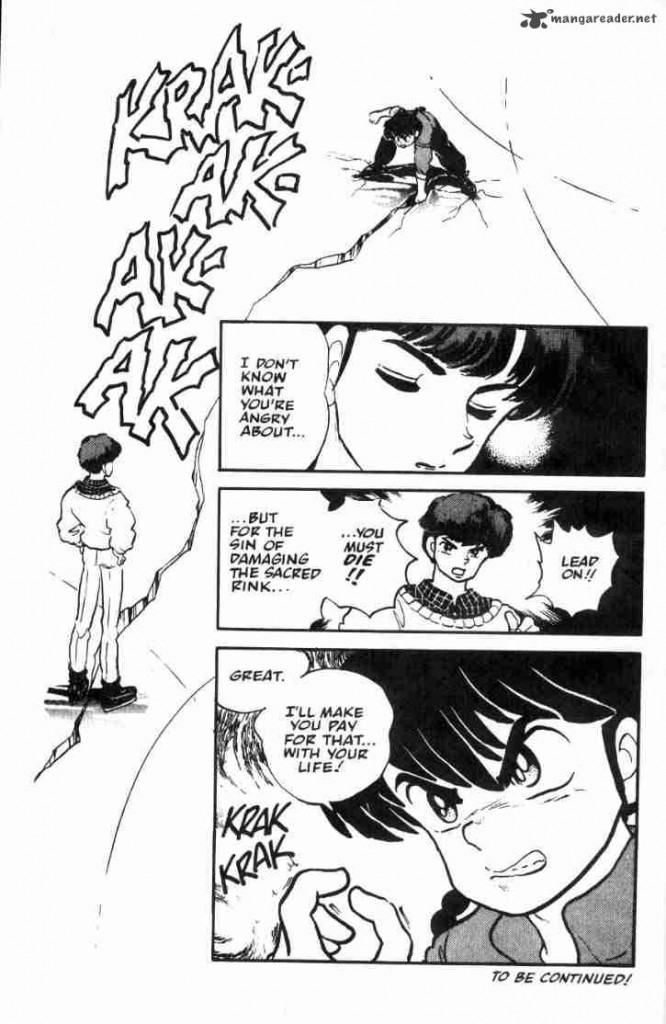

A page from Blueberry – note the A and B in the bottom right corners of the half pages.

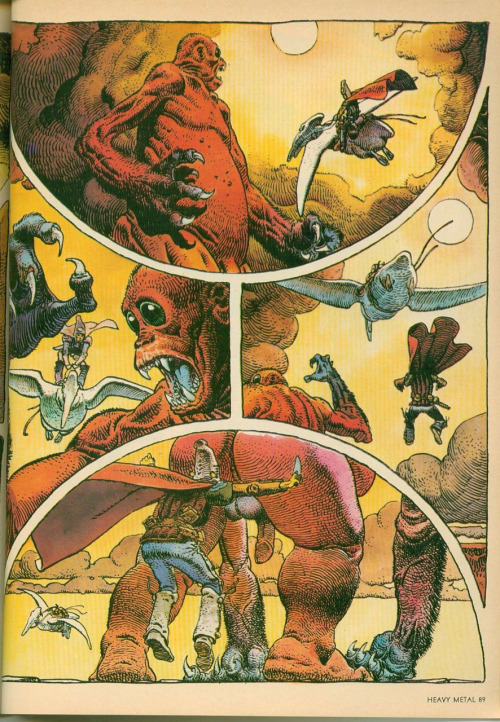

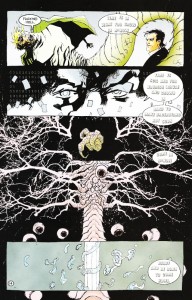

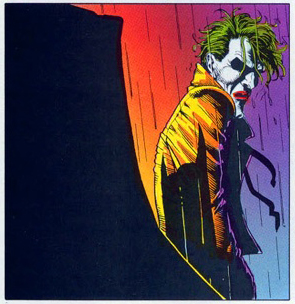

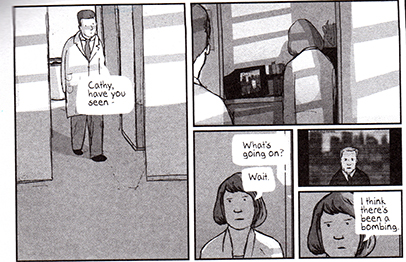

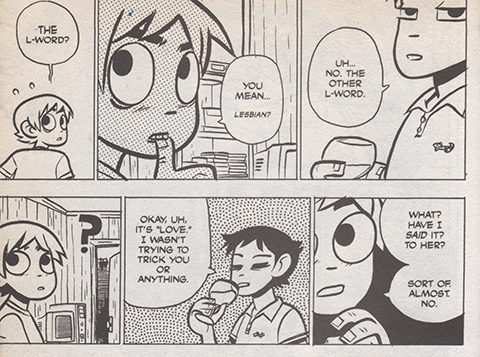

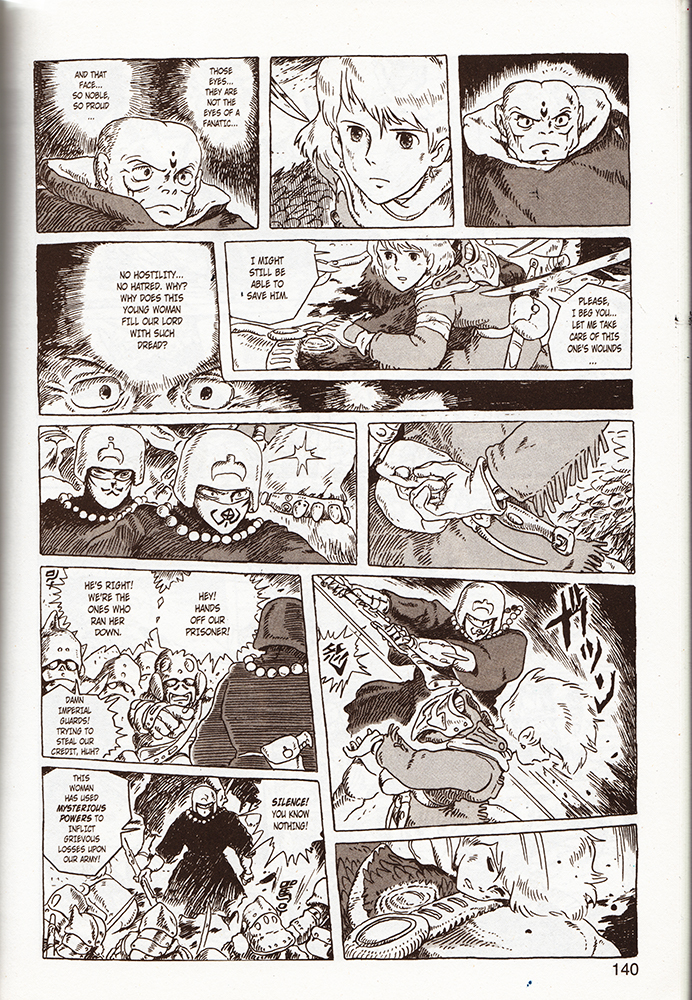

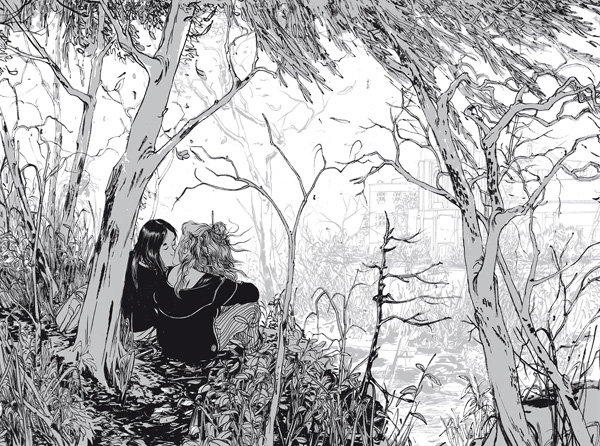

But when you look at the material that Moebius and Druillet were producing in Metal Hurlant, you can really see a massive revolution in format. The pages are not formatted to be chopped in half for serialization – the page layouts are a direct challenge to the old commercial methodology. In addition, the fact that three or four pages were printed at once to present a complete story in a single issue was a major shift.

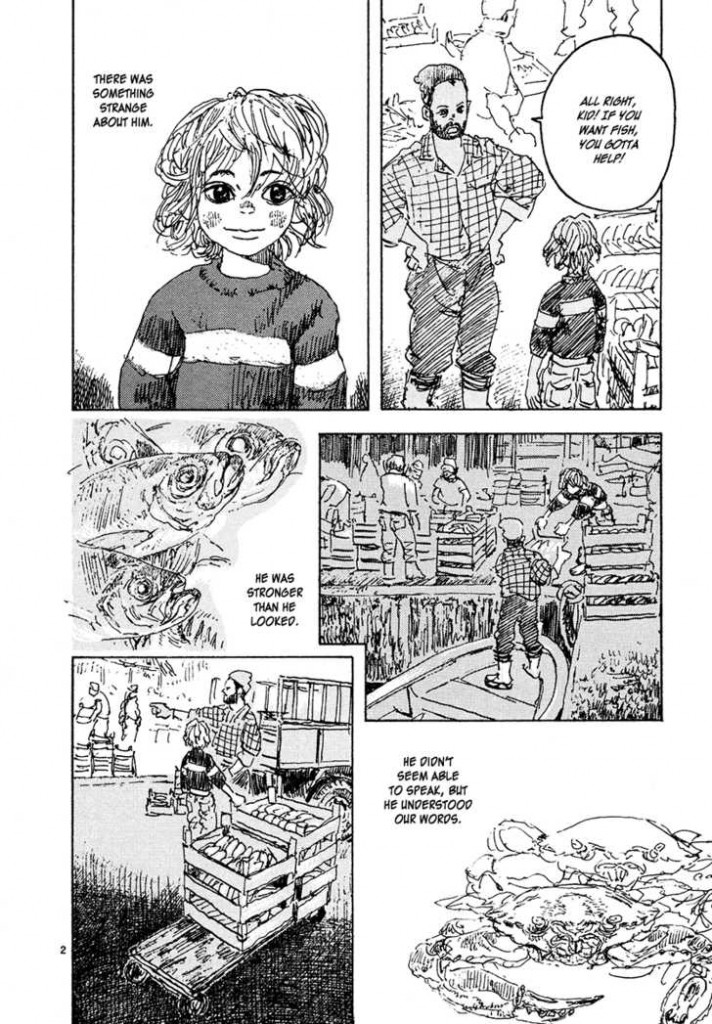

For contrast, a page from Arzach, also by Moebius

It’s probably not a coincidence that Les Humanoïdes Associés came mostly from the Pilote stable of artists. They pushed against the solid editorial format of the establishment and, when that didn’t get them where they wanted to go, they went out and formed their own magazine – something that just about everyone in the Francophone market did at one point or another. There were many, many anthology magazines on the stands at the time and still are.

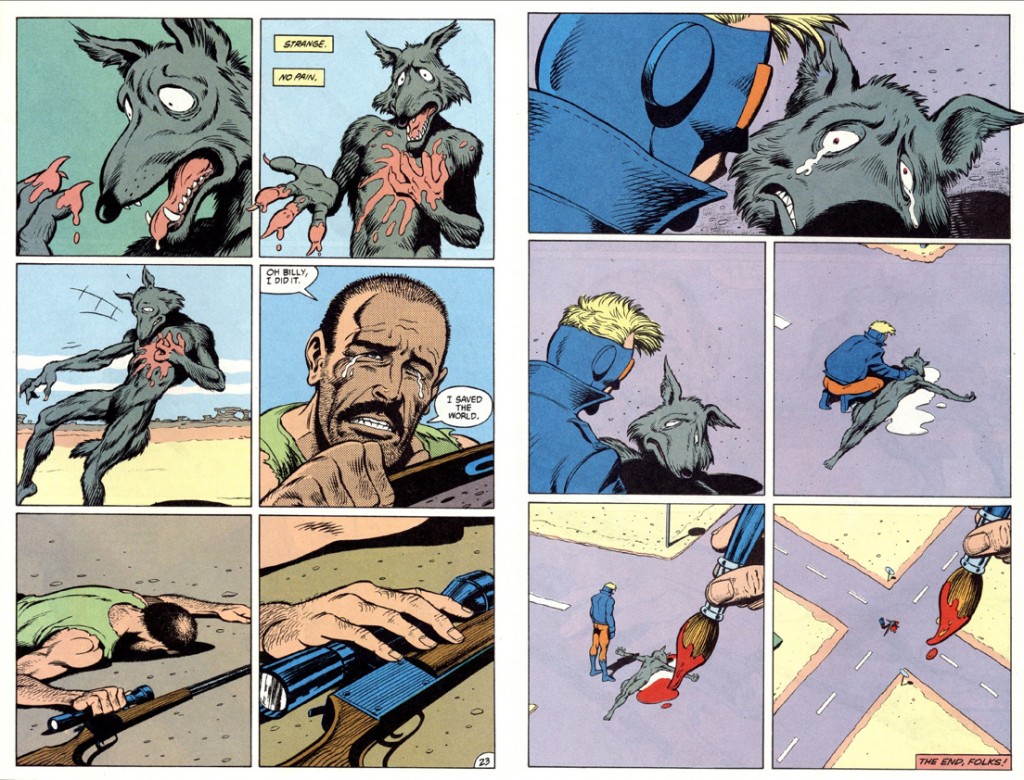

The Metal Hurlant revolution can be better understood to an Anglophone comics audience as analogous to the Image revolution – a bunch of artists got together and did their own thing because they wanted more creative control. It’s a shame that this part of the history isn’t better understood, because it would have been more appropriate to compare the Image revolution to the Metal Hurlant revolution because of the order they occurred in. C’est la vie.

After Metal Hurlant proved to be a successful commercial powerhouse, the BD market shifted. Not everything had to be in half-page increments anymore and there were far more experiments in format. By the early 80s, things like Les Cites Obscures by Schuiten and Peeters started showing up in complete albums without serialization and multipage stories by Caza were appearing in Pilote.

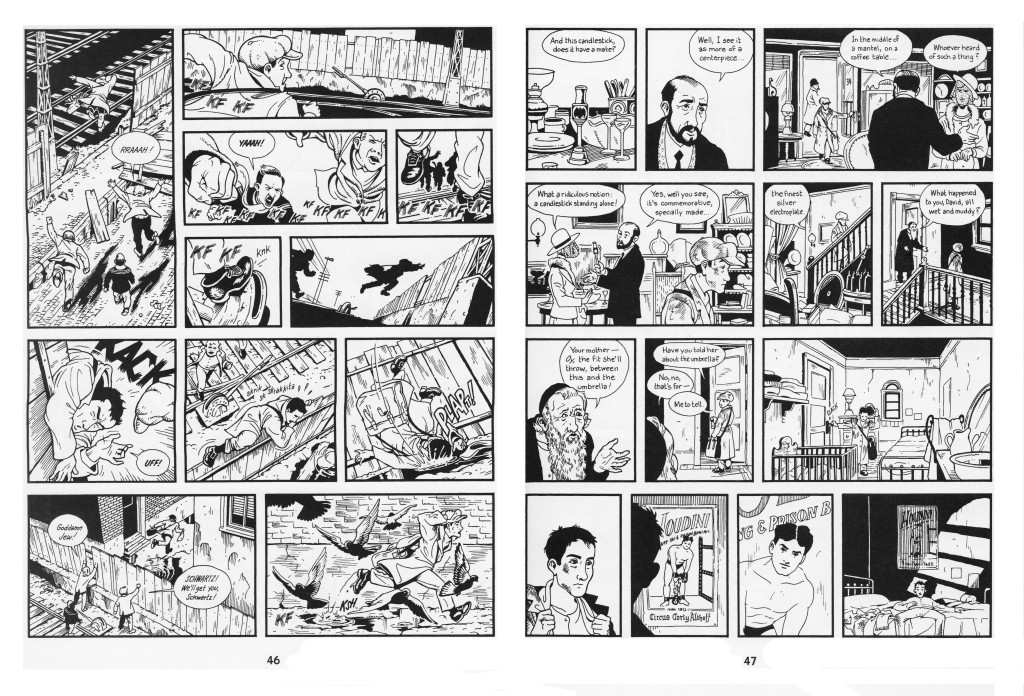

When Heavy Metal appeared on American newsstands in 1977, there were already a number of other anthology titles floating around. Not quite part of the underground movement, these were referred to as the “ground level anthologies” (because they were a step above the underground and a step below the mass market) and, to Anglophone eyes, Heavy Metal fit right in.

The granddaddy of these was (in my opinion) witzend, which started in 1966 and was published irregularly through the mid 80s. Star*Reach and Hot Stuf’ were around in the early 70s and provided venues for artists like Howie Chaykin and Rich Corben, who went on to make great material for Heavy Metal.

Interestingly, 2000AD also started in 1977.

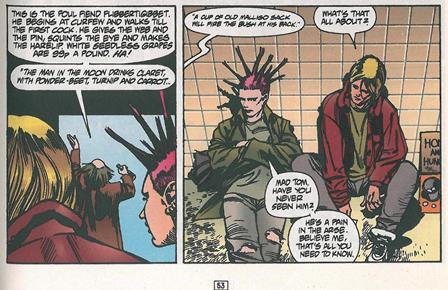

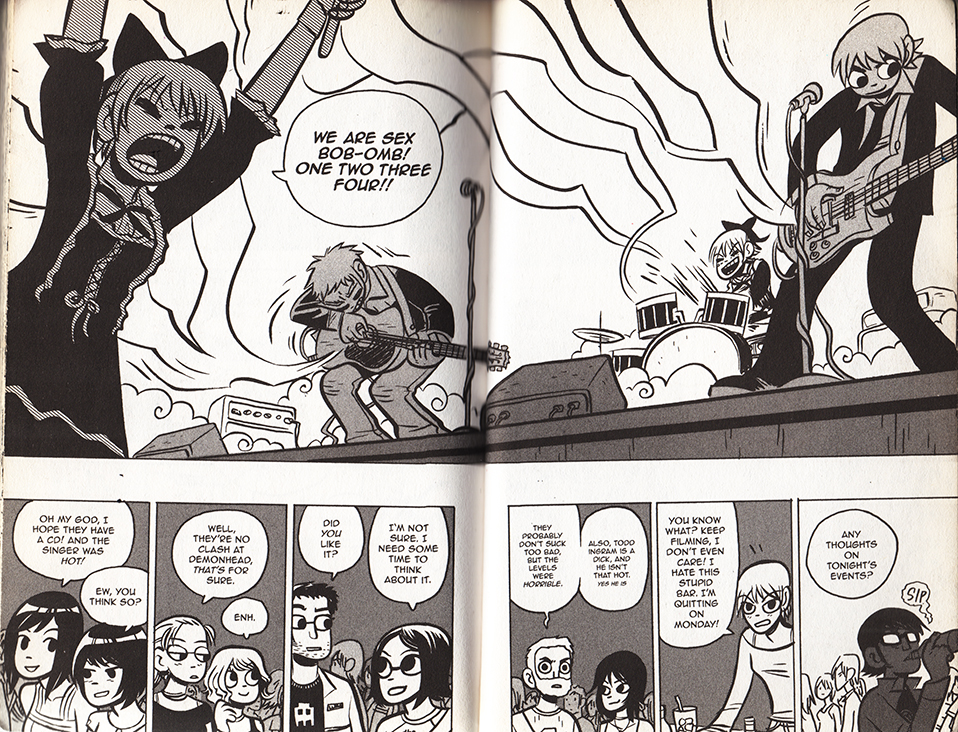

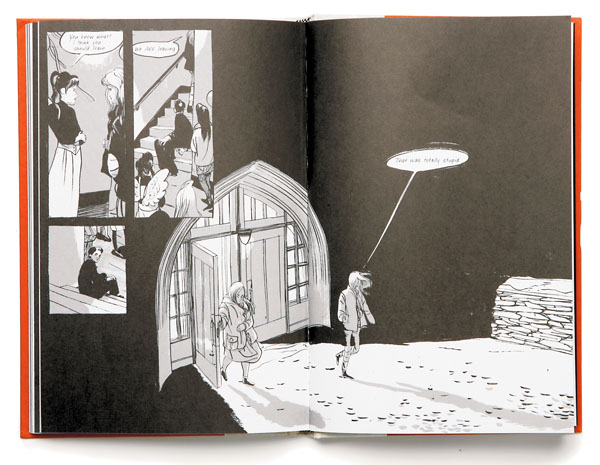

By the early 80s, the ground level anthologies business was very popular. Every little (and some not-so-little) publishing house was putting out their own anthology – Eclipse, Epic Illustrated, Warrior, Raw, Weirdo, 1984 (later 1994) all came and went during the heyday of Heavy Metal. There was even a short run of a Scottish anthology in 1980 called Near Myths that featured a strip called Gideon Stargrave by a young up-and-comer named Grant Morrison.

It’s entirely possible that the young Morrison saw Heavy Metal in punk terms because that was what he was immersed in when he was 20, when he was working on an anthology created in clear imitation of Heavy Metal. But that doesn’t mean that Heavy Metal had any kind of real “punk energy” during that period. Maybe we are predisposed to define all future revolutions (including the ones we create) in terms of the first revolution that we live through.

A really revolutionary act would be for Morrison to go back and read those issues with fresh eyes and see what made Heavy Metal distinct (the European material, which none of the other ground level anthologies had in such a high volume). In the Entertainment Weekly article, he is quoted as saying “One of the things I like to do in my job is revamp properties and really get into the aesthetic of something, dig into the roots of what makes it work, then tinker with the engine and play around with it. So for me, it’s an aesthetic thing first and foremost.”

He also plans to write and create original material for the magazine, which doesn’t fill me with a lot of hope that he will, in fact, recapture that original aesthetic – mostly because the most honest way to do that would be to hire revolutionary European creators and give them room to really challenge the status quo. But I don’t see him trawling Angouleme for new creators anytime soon.

One thing is certain: given my commitment to read the entire run of Heavy Metal, I’ll get to his issues eventually. I’m currently on the 1989 issues, so that will be three to four years from now, based on my current reading speed. At this point, though, I really don’t feel a sense of urgency to jump ahead and read them as they are released, based on his remarks.