Editor’s Note: This is the week my book, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism is released. I’ve put together a week-long roundtable to celebrate.

________

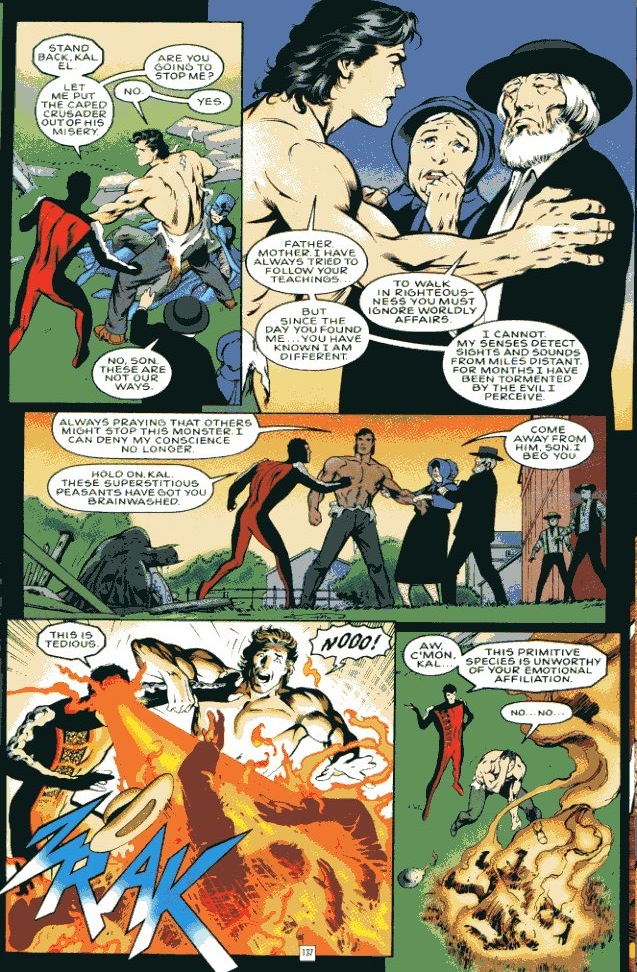

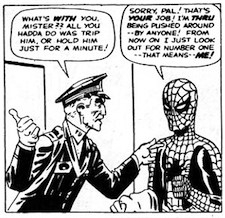

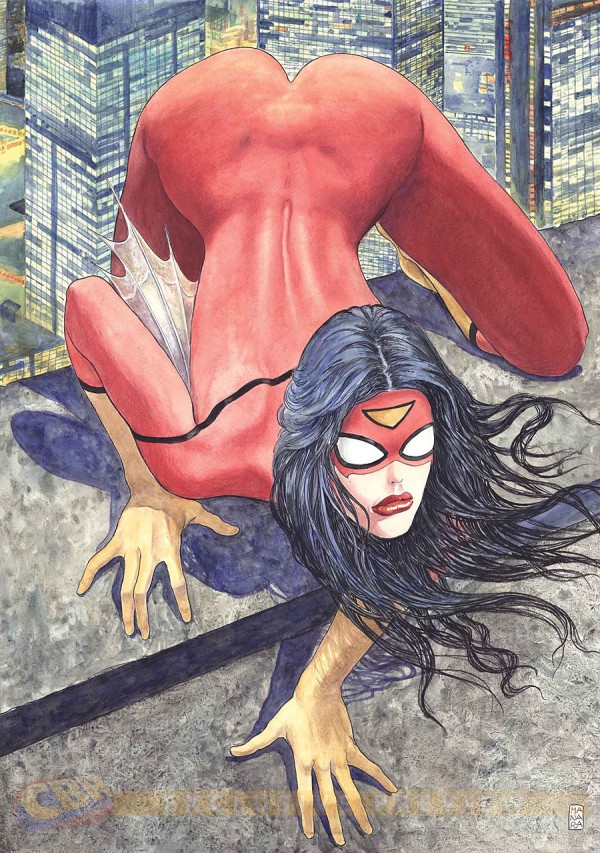

There’s long been talk about how superhero stories are getting ambitious. The histories and planetary layouts of comic book universes, once created haphazardly, are solidifying into un-breachable canon. Characters from diverse series will “cross over” and team up during climactic event episodes. Meanwhile, film adaptations attract talented, occasionally brilliant, actors, and pack in enough pseudo-philosophy and current polemics to merit thoughtful reviews, (or at least avoid outright dismissal.) Captain America fights military surveillance, dancing around his own imperial baggage. The Nolan Batman trilogy harnesses fearful imagery of mental illness and the Occupy movement to apologize for its own elitist and authoritarian nature, which it presents as perversely anti-heroic. Guardians of the Galaxy seems aware of its own ridiculousness, and so avoids stigmatization as overt camp. The cinematography, special effects, costume and set design are top-notch. The appearance of being an ambitious film counts more than the internal logic of the final work. It counts more than actual narrative ambitions, like championing a truly underdog protagonist, envisioning utterly alien societies and technologies, or portraying good and evil in an insightful way. Contemporary superhero narratives indulge in emotionally disconnected escapism, sexuality and violence, all carefully leavened with inside jokes and buddy comedy. These films, and their comic source material, feature all the bells and whistles of ambition, while being safe projects at heart. It’s a sad day when a quippy, trigger-happy raccoon (with a heart of gold) surprises audiences —he’s written exactly according to Marvel formula.

Some of this might be endemic to the superhero genre; in the words of Noah Berlatsky in a recent piece in The Atlantic,

“Tony Stark [of Iron Man] invents new magical energy sources three times before breakfast, but he uses them mostly to punch Thunder-Gods in the head, rather than, say, to completely transform the world’s technology and economy.”

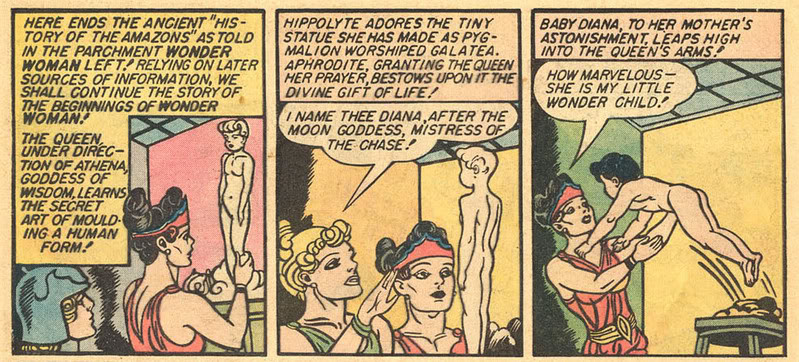

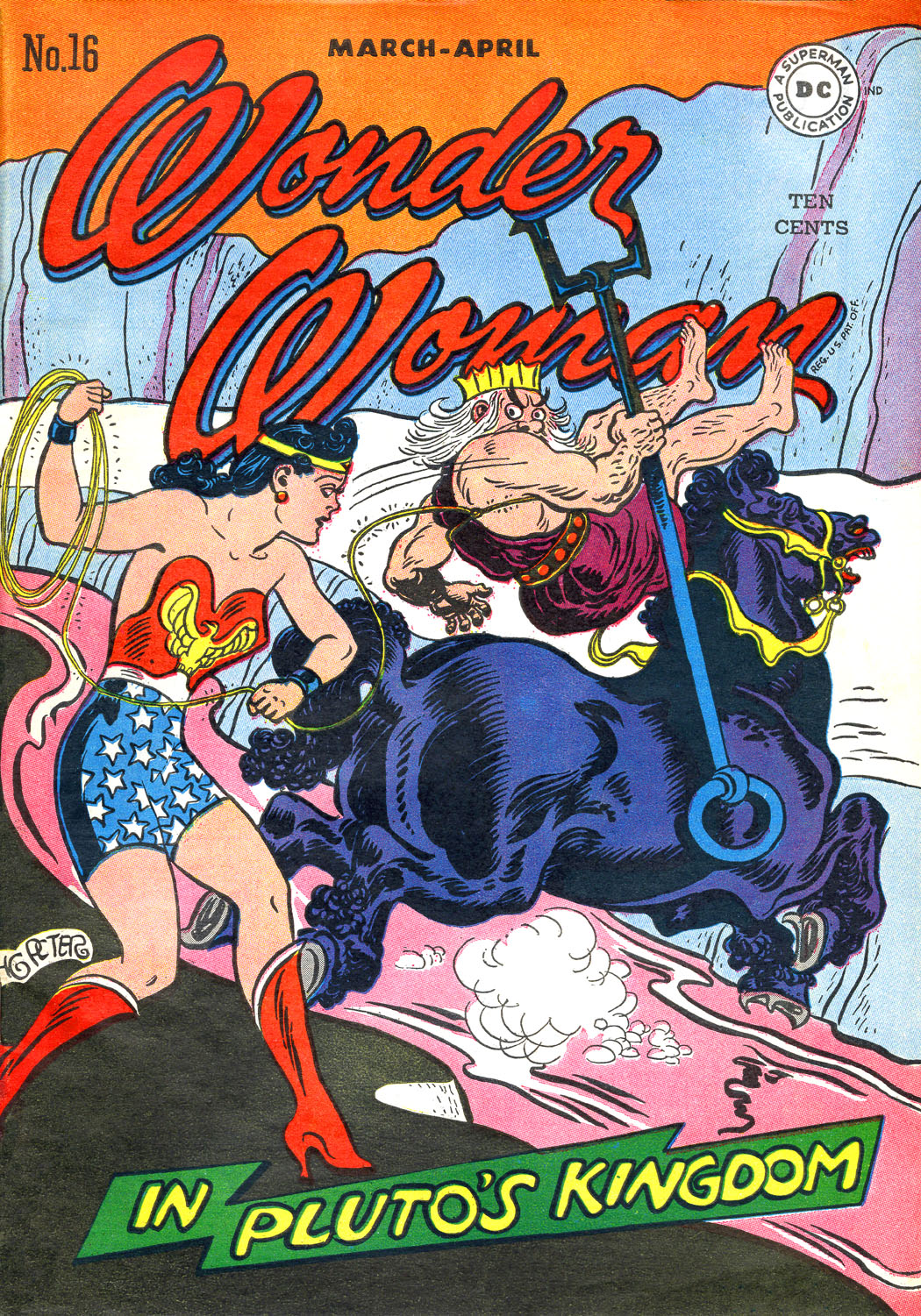

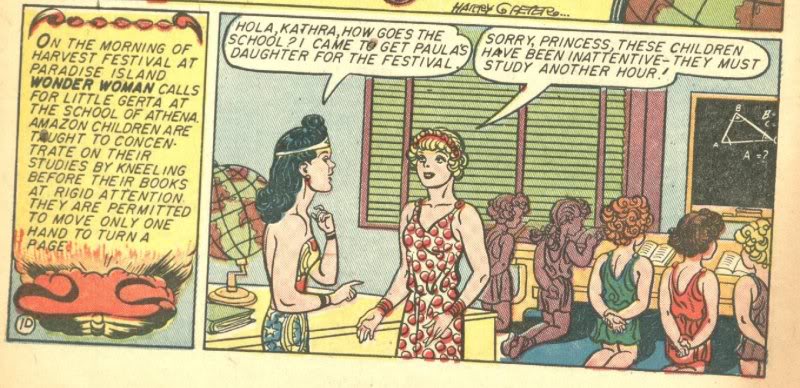

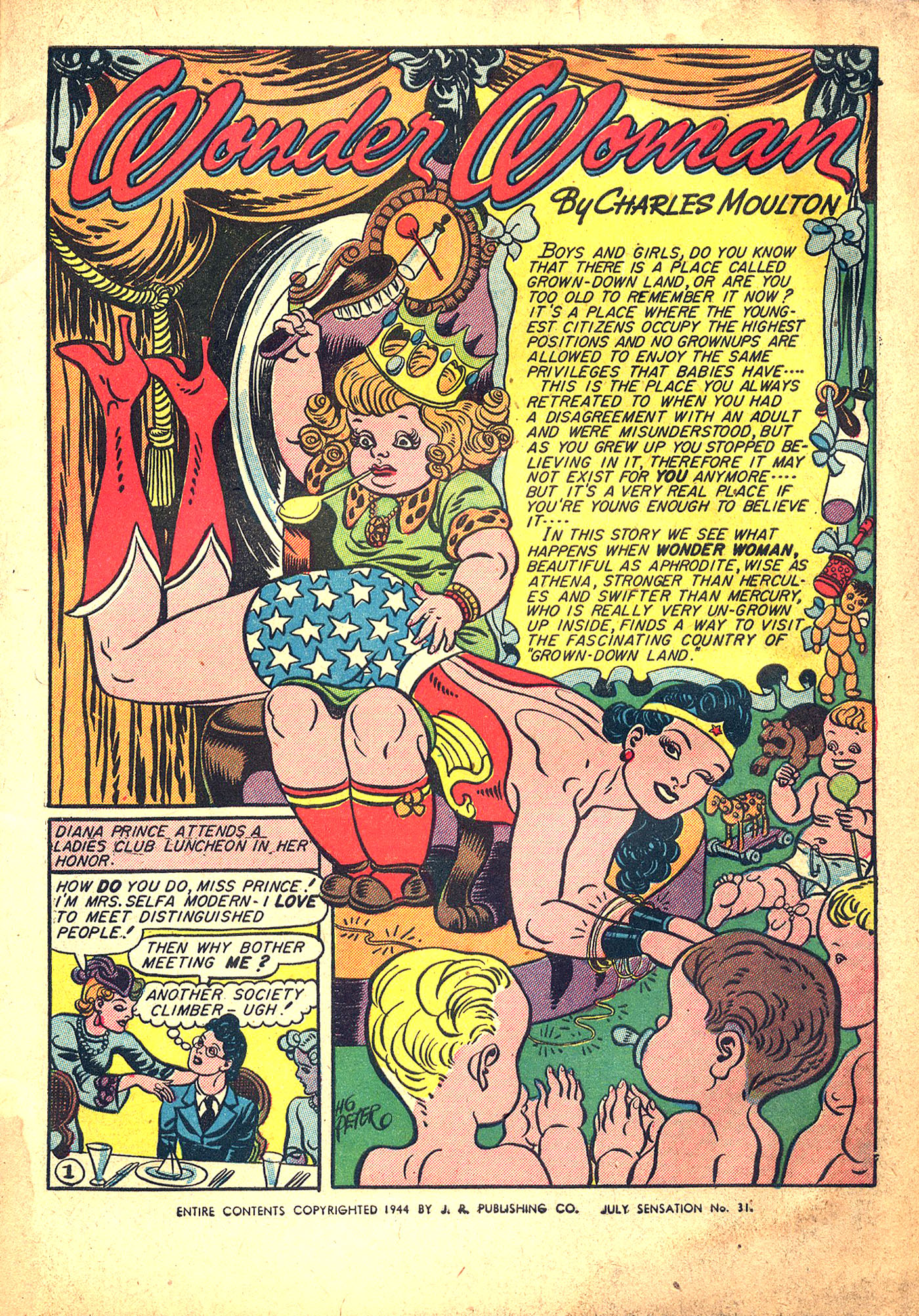

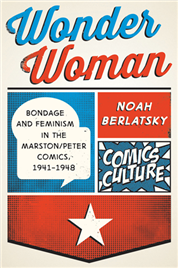

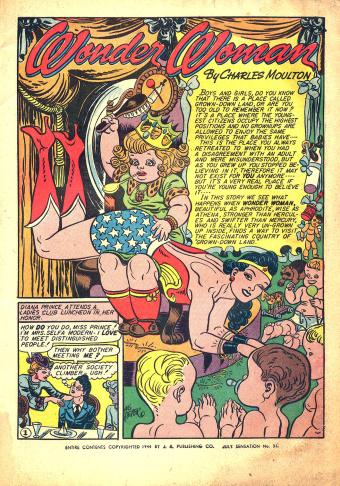

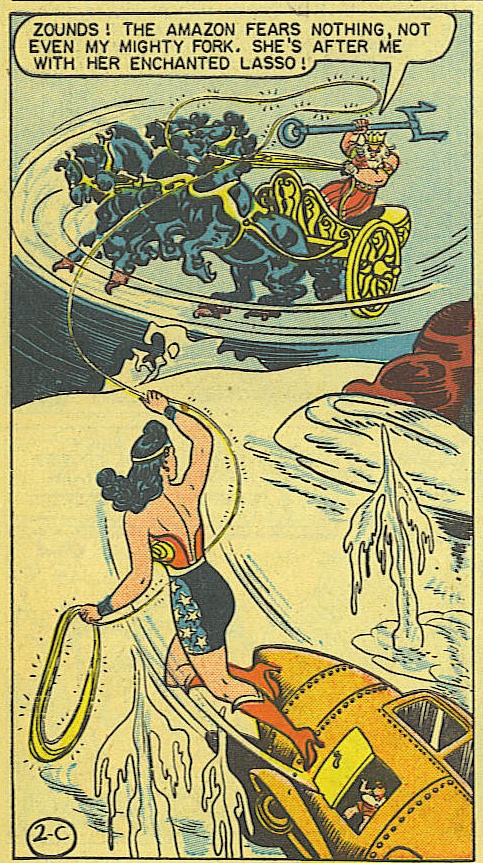

It didn’t have to be this way. Noah’s recent book, Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948, records an alternative which had been present at the dawn of superhero comics. Unlike Superman, the original Wonder Woman comics were not a personal fantasy of power and assimilation, born already calibrated to the yearnings of depression-era, immigrant, and wartime youth. The Wonder Woman comics were an intentional manifesto, meant to instill radical concepts of femininity, masculinity, sexuality and heroism into children. Noah’s book elucidates William Marston’s radical philosophies and agendas, which informed every aspect of the forties run. If not for the kaleidoscopic visuals and zany scenarios, the barely-sublimated kinkiness and infectious fun, Wonder Woman might have been remembered as being propaganda designed to re-educate America’s youth. Instead, Marston and artist Harry Peter created one of the most original and unclassifiable comics in history. Despite its initial success, publishers didn’t know what to do with it, and America came out of the war more sexually repressed than it had entered. The Marston/Peter run hangs off comics history like a forgotten evolutionary branch. The indomitable Diana of the original comics faded away, and less interesting archetypes convergently evolved to take her girdle, to fit DC’s limited ‘heroine’ niche.

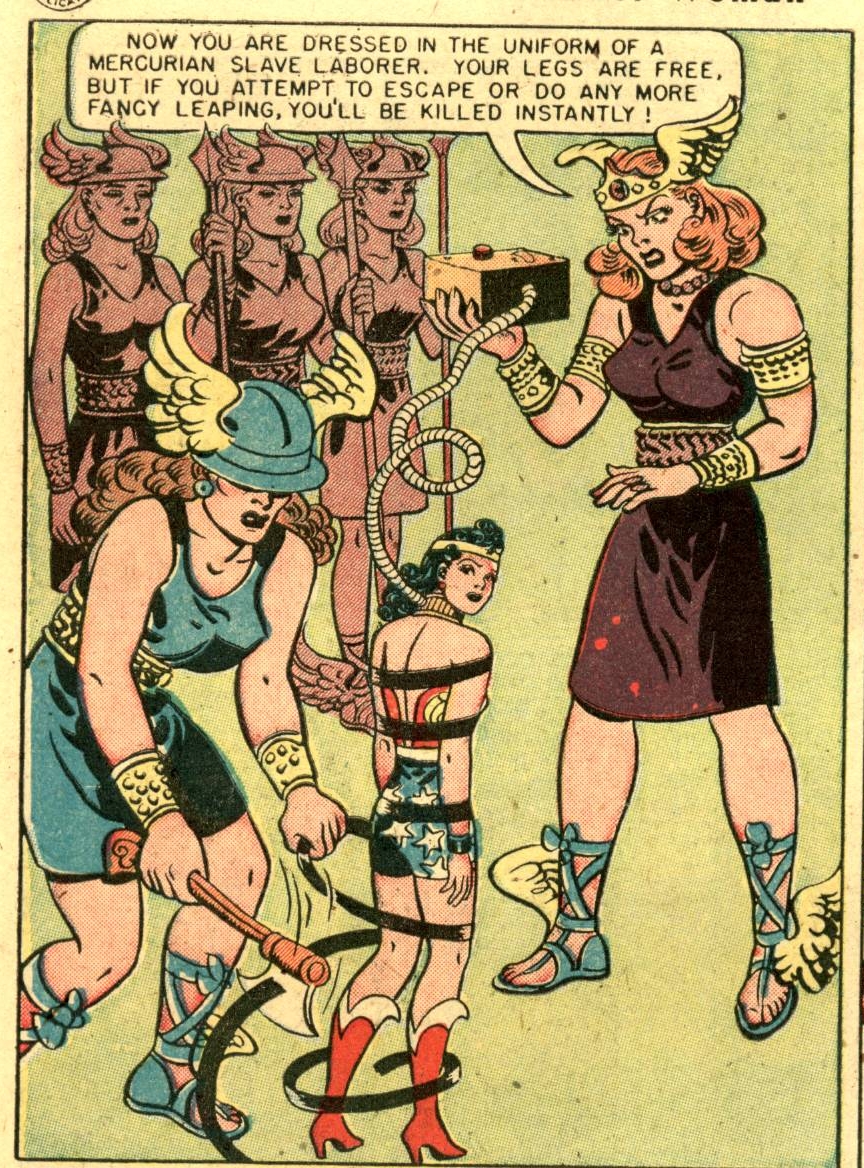

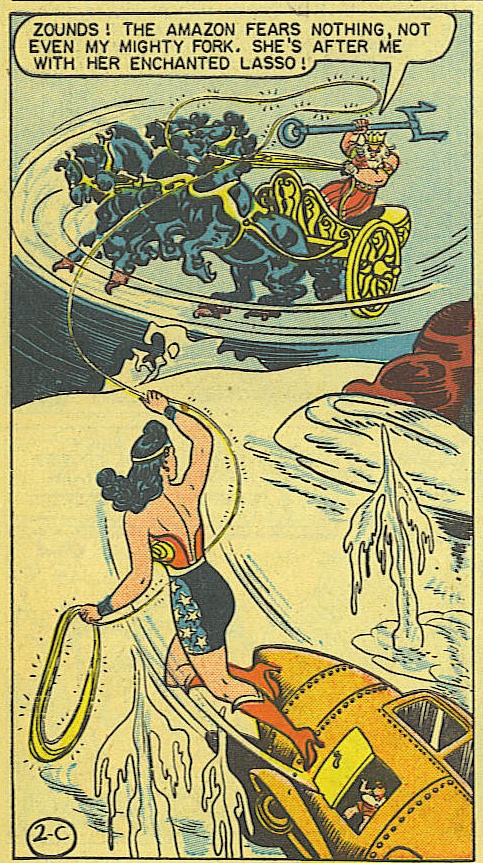

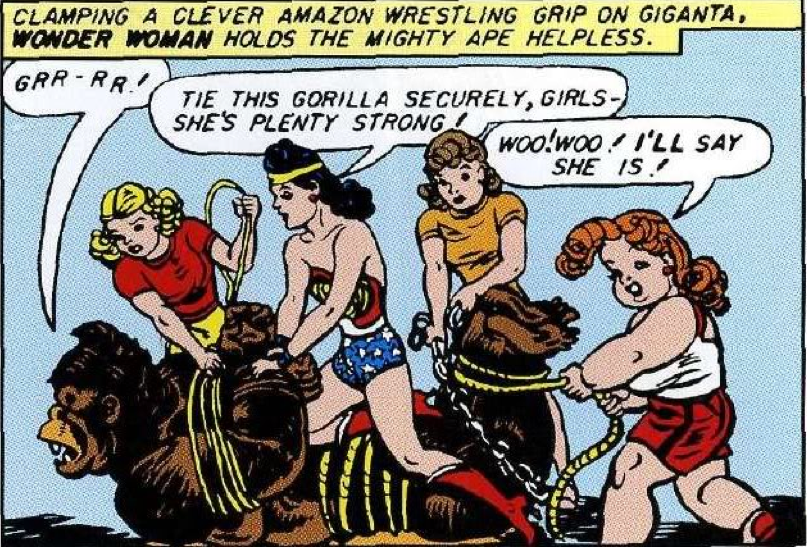

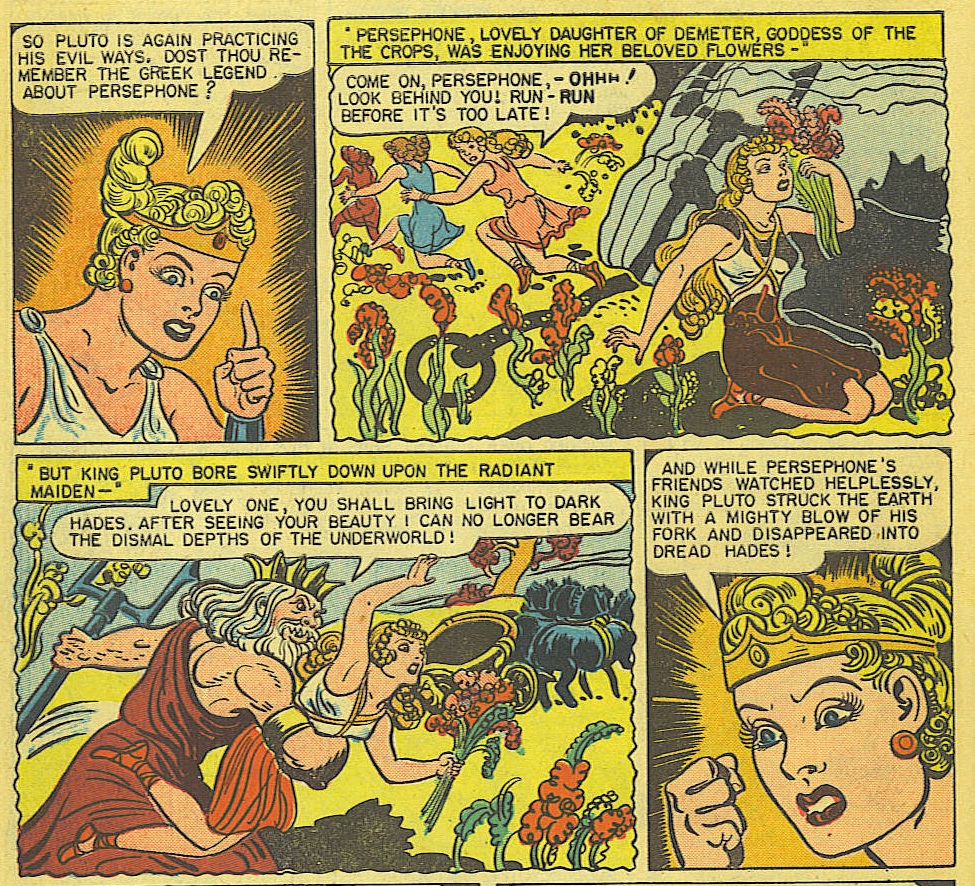

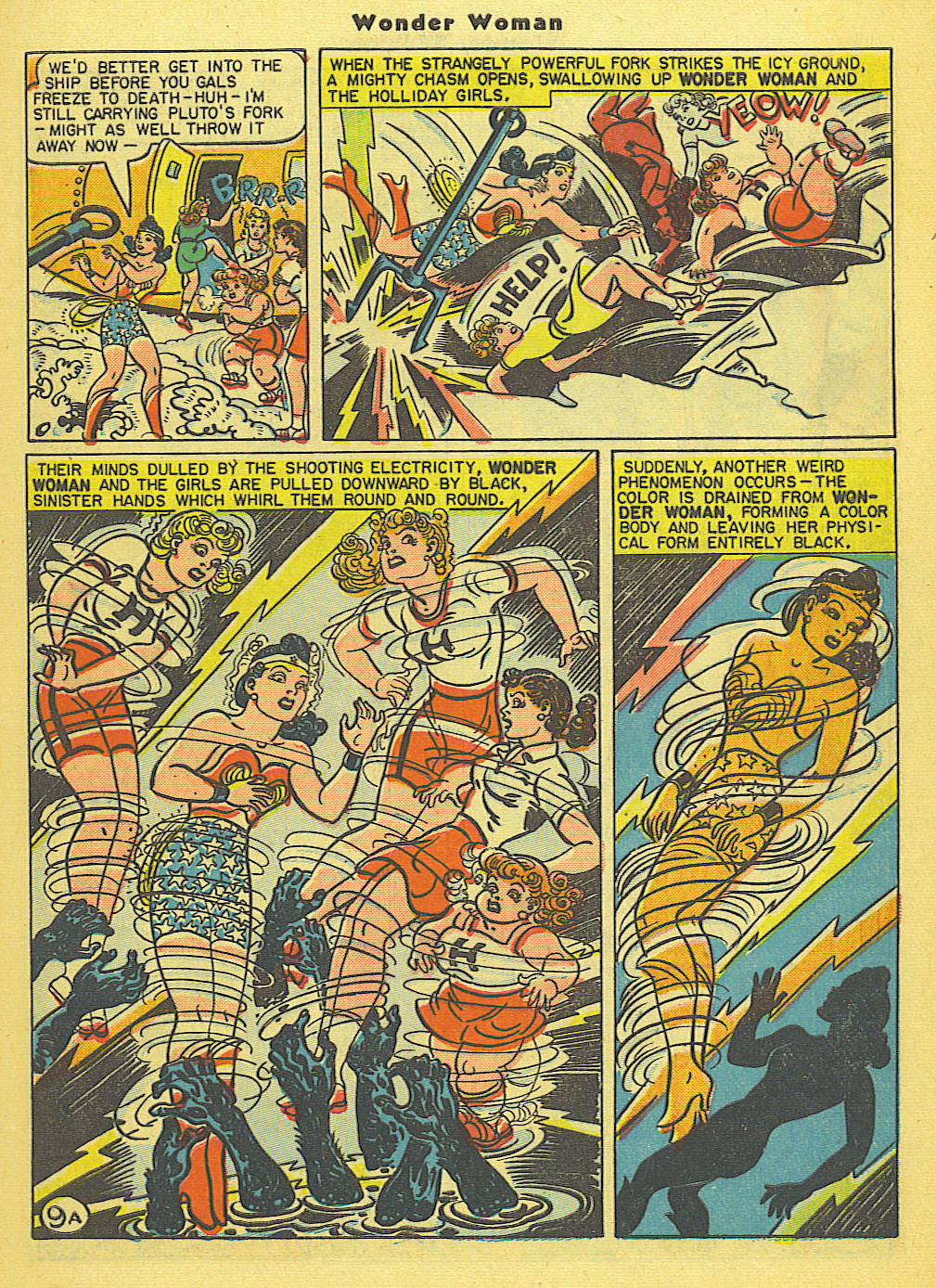

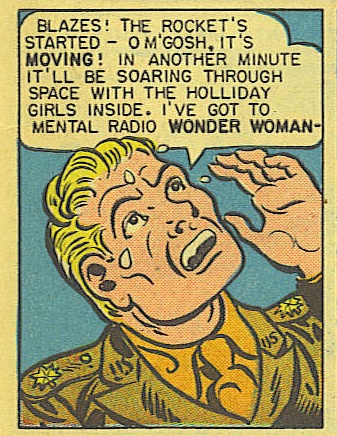

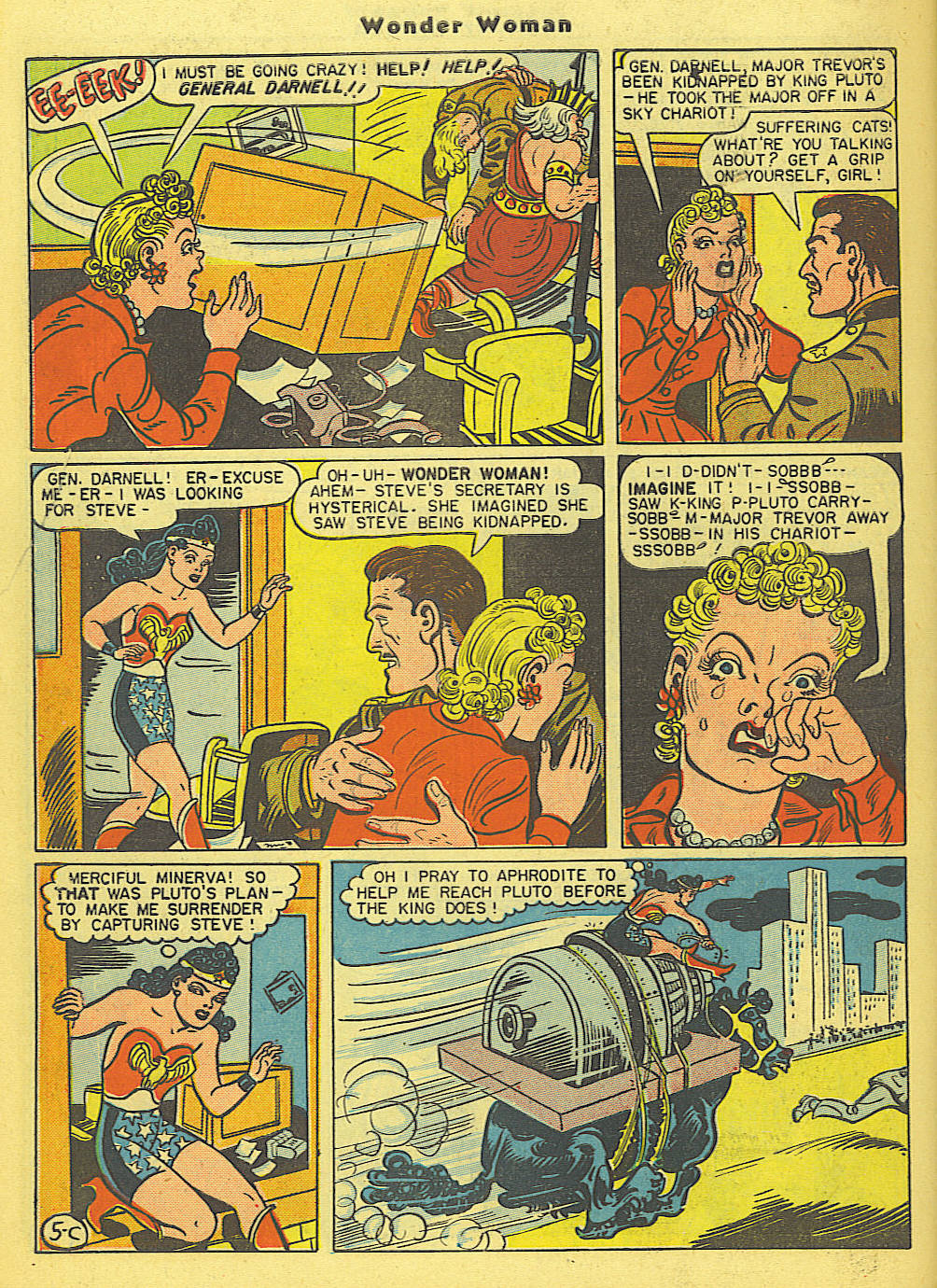

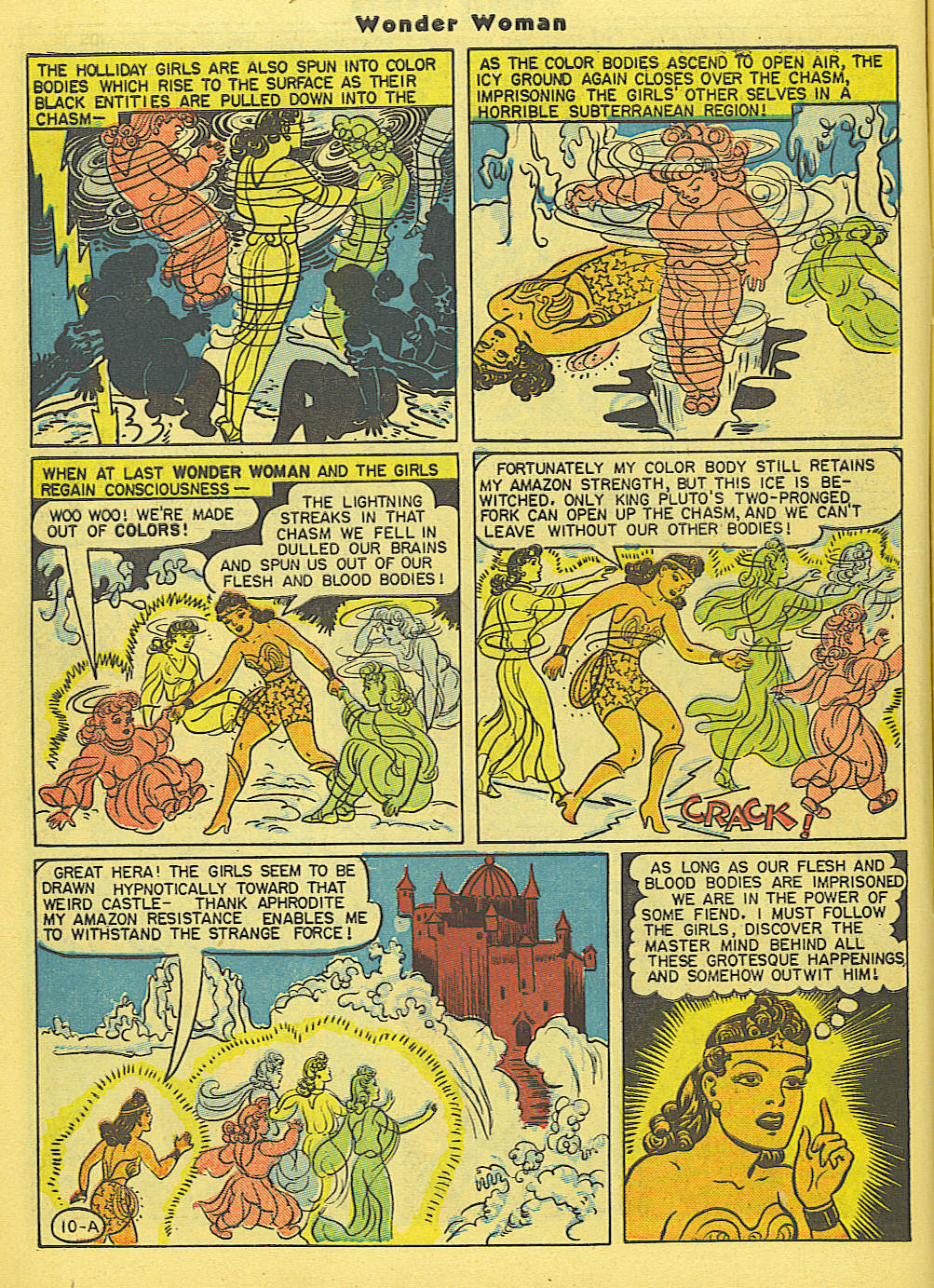

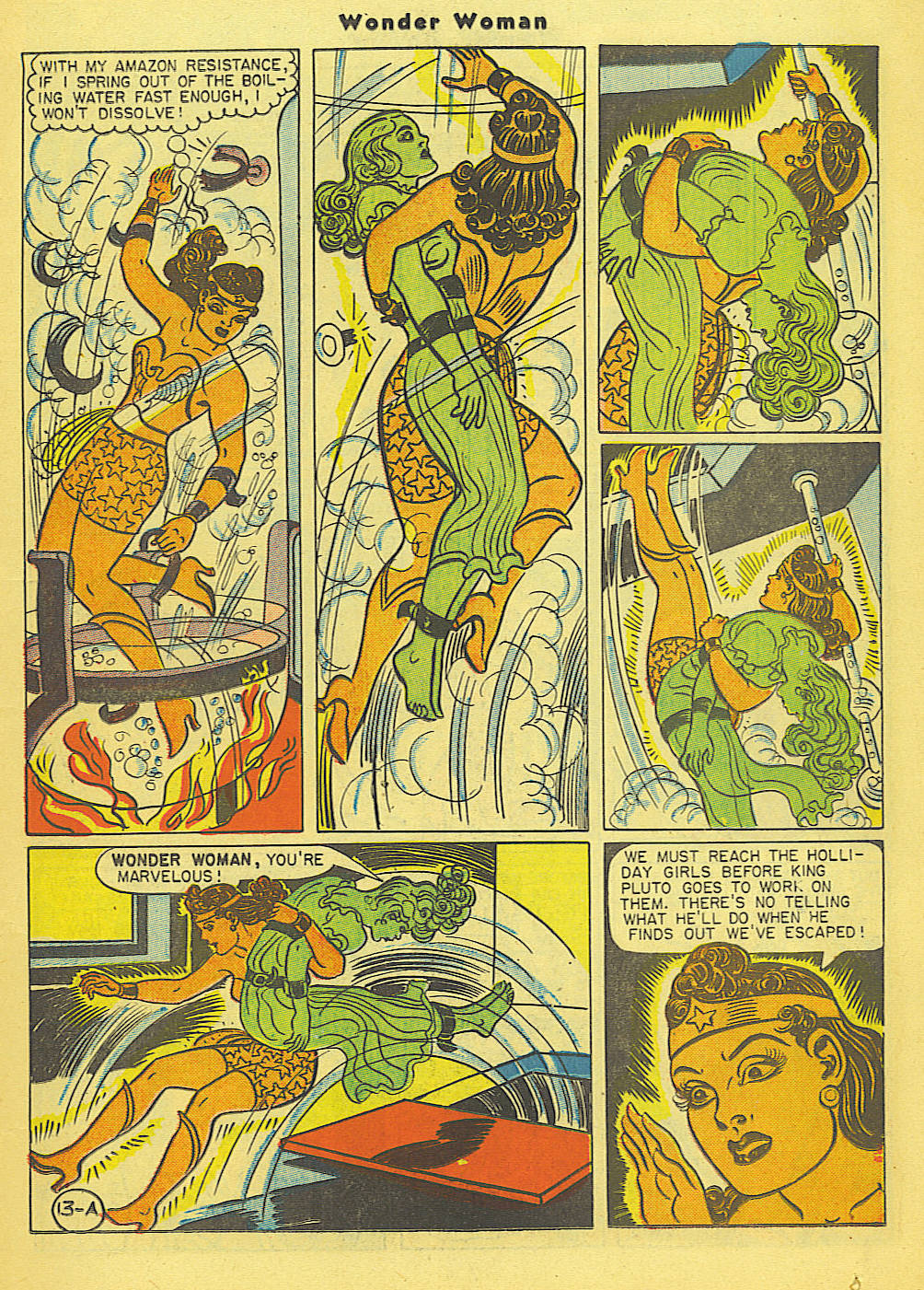

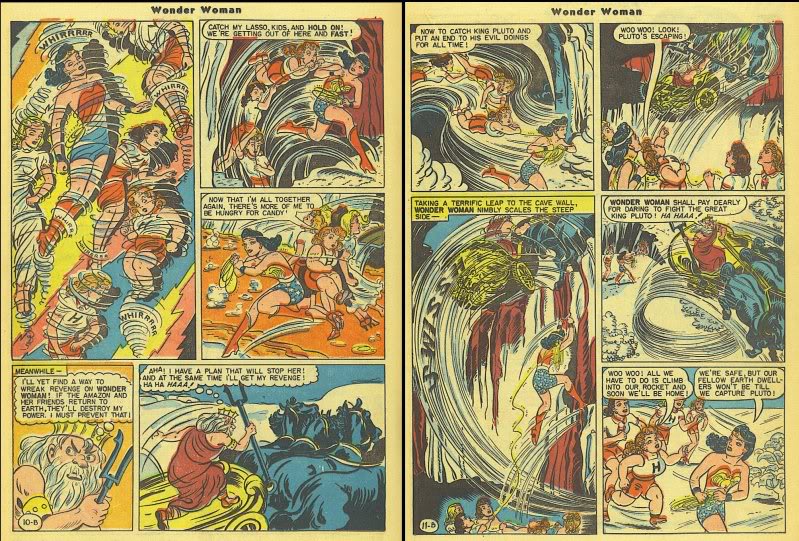

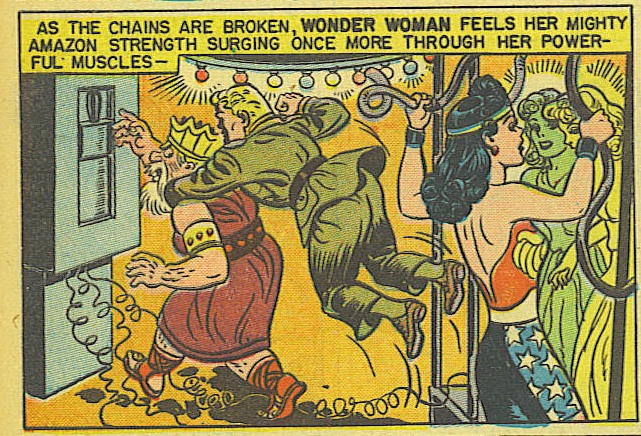

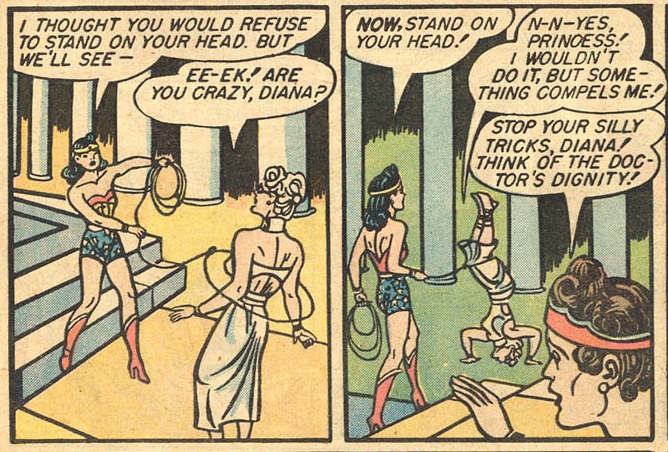

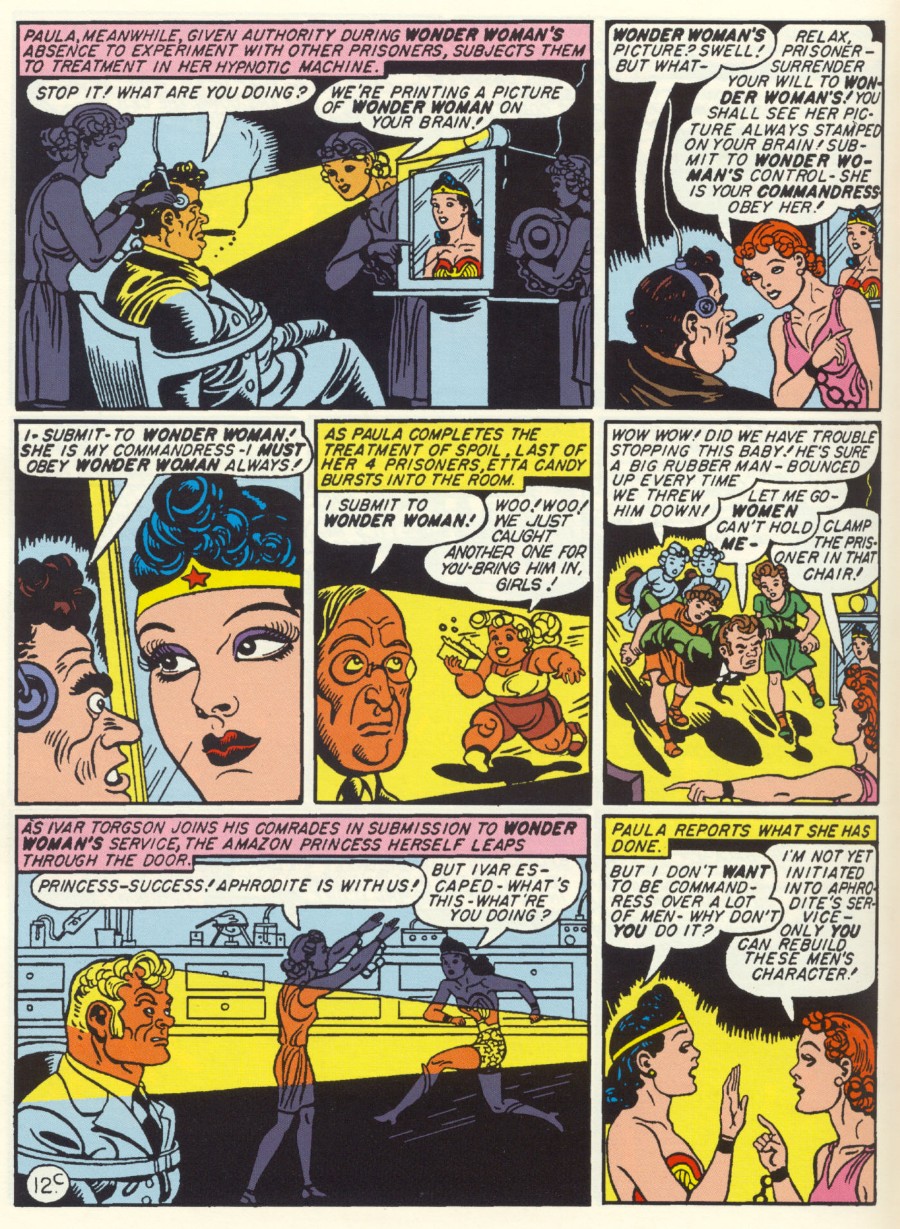

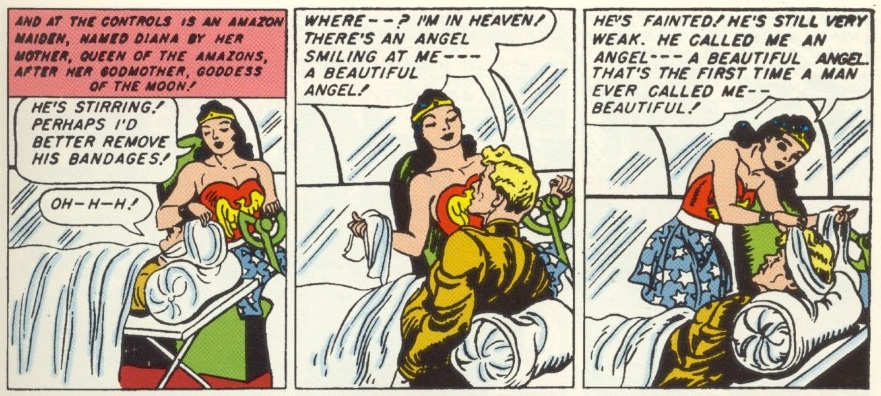

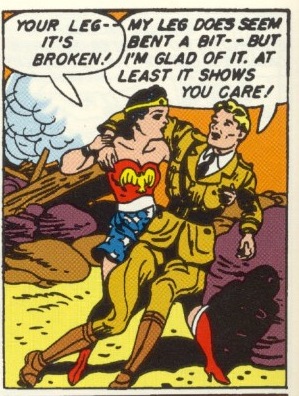

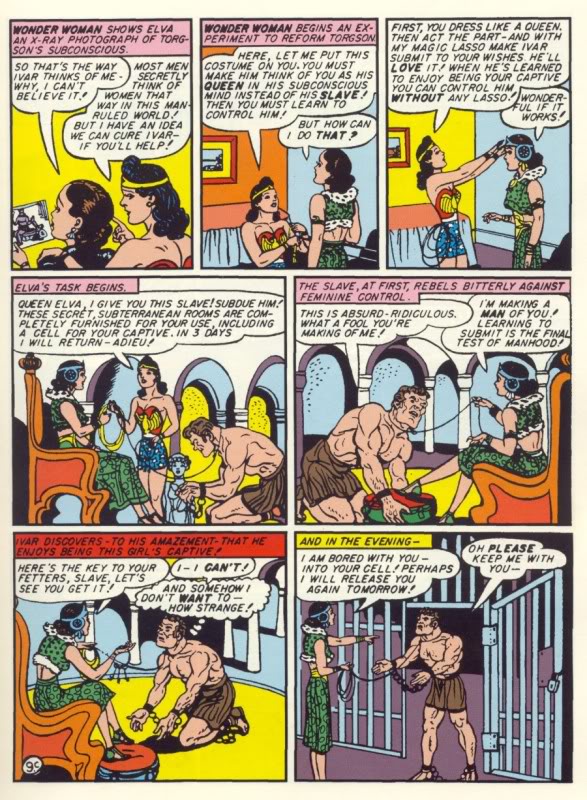

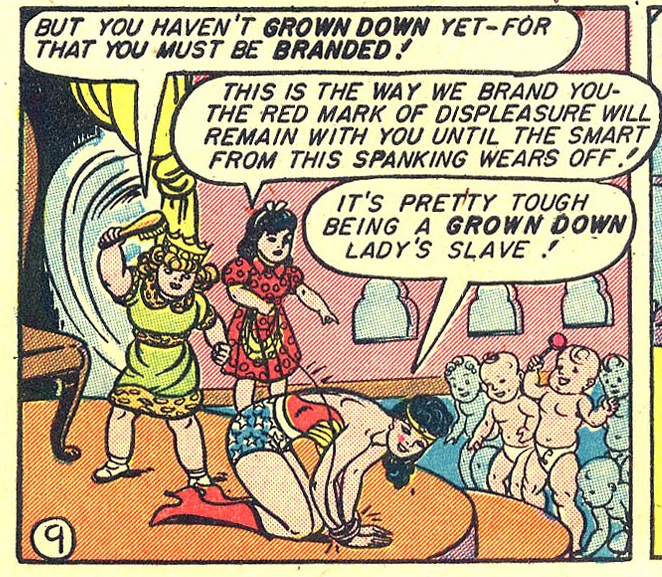

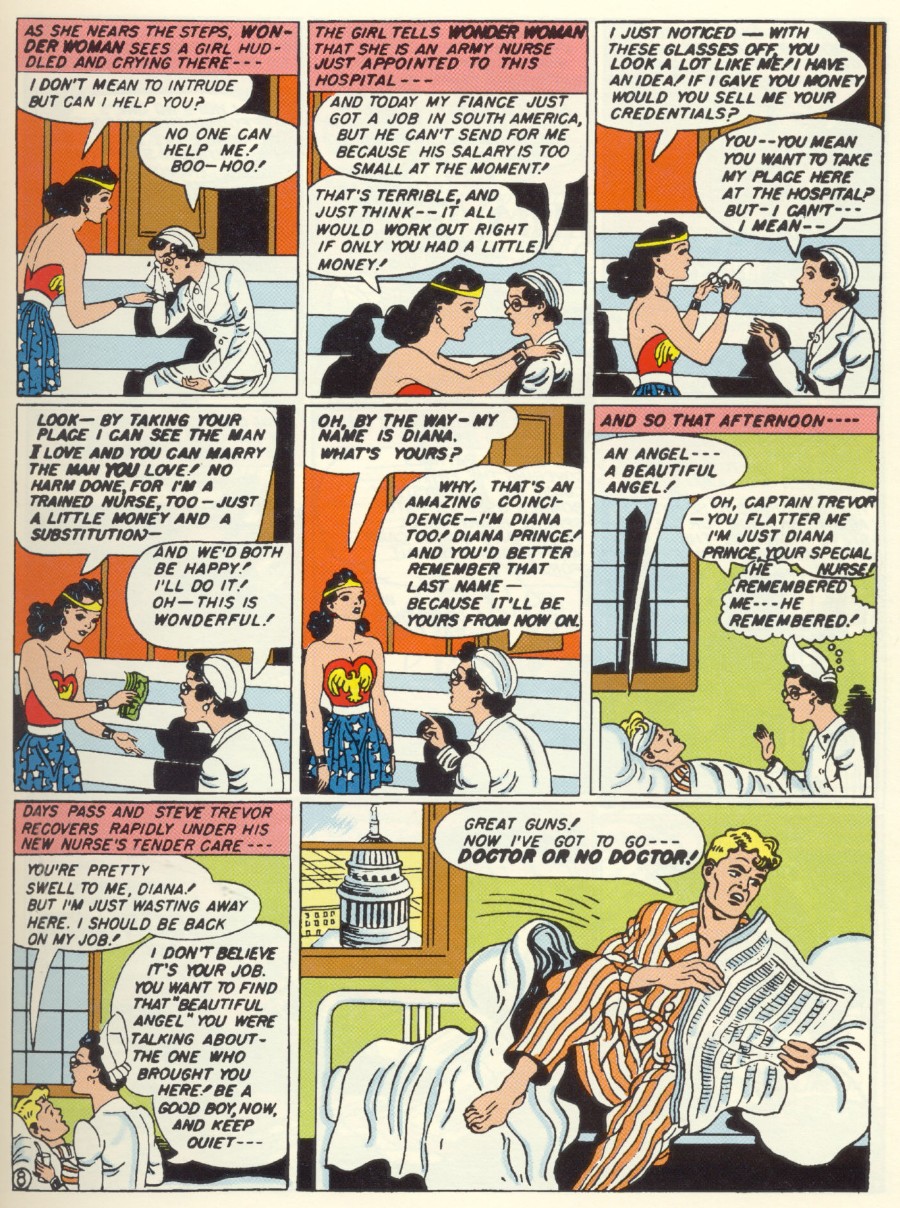

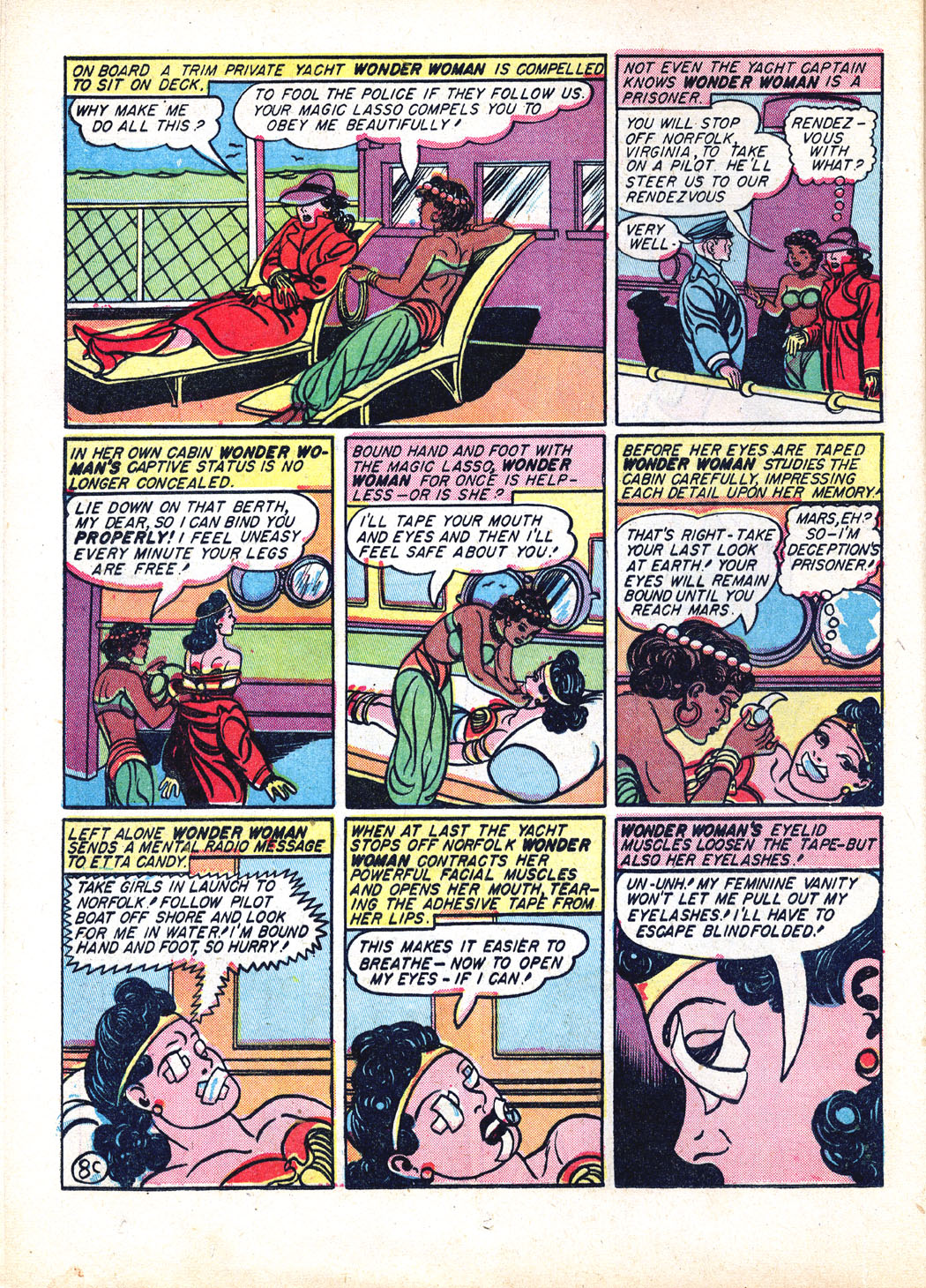

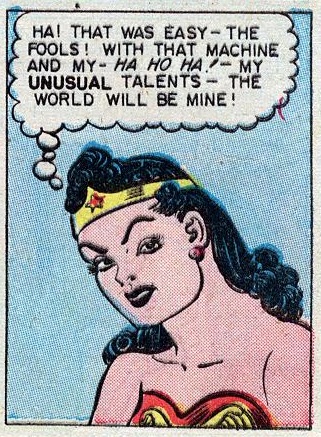

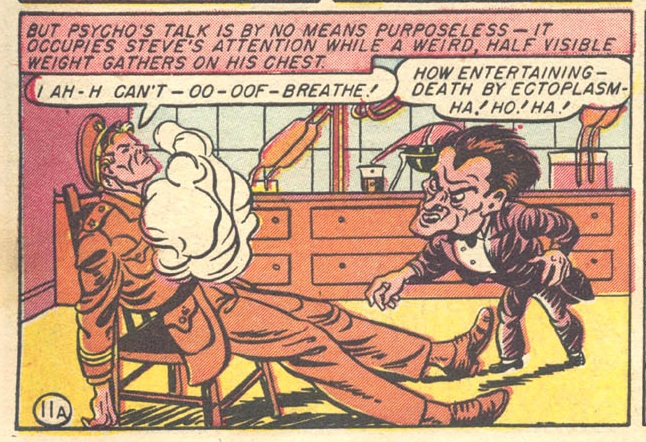

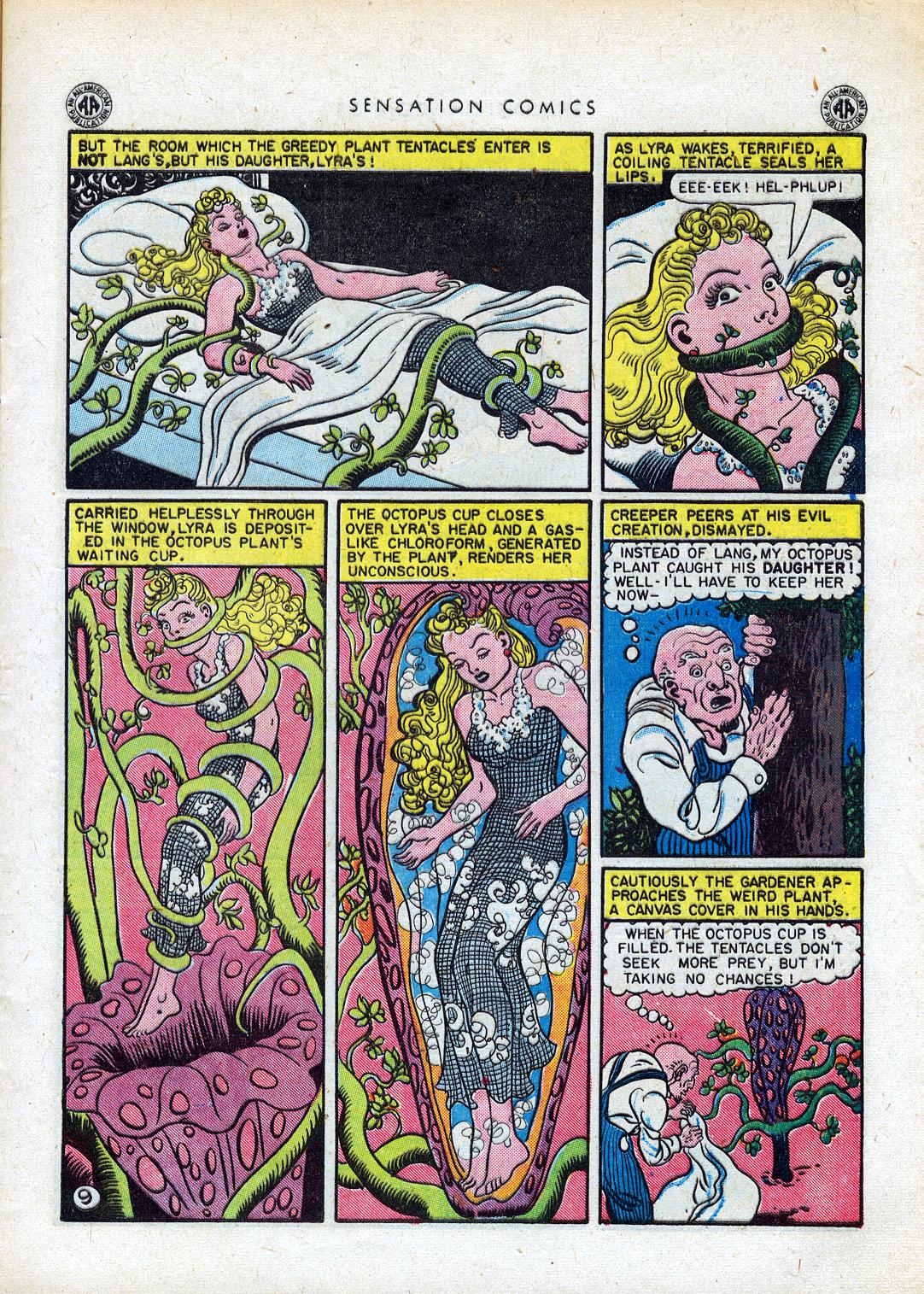

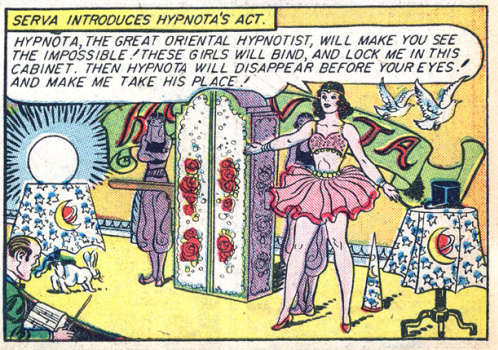

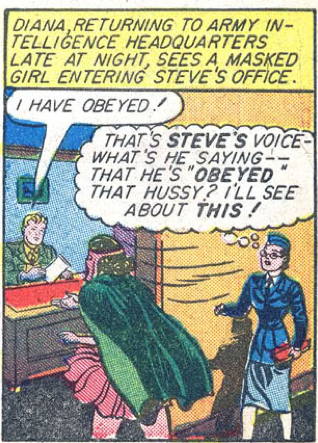

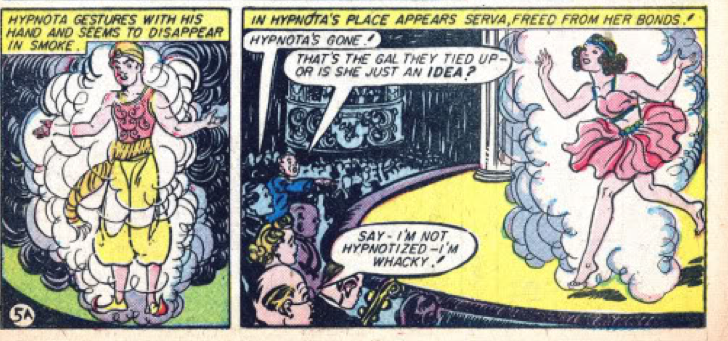

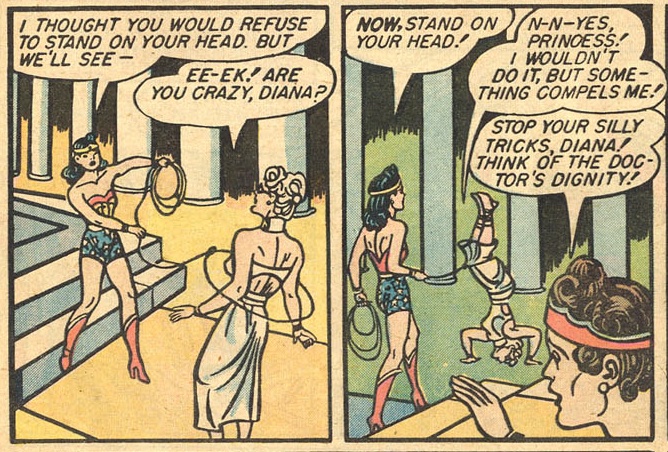

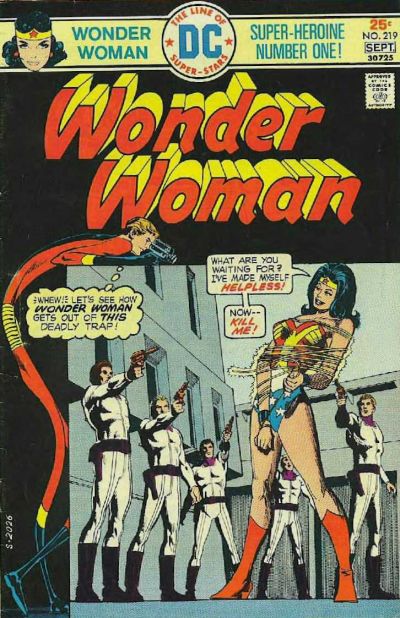

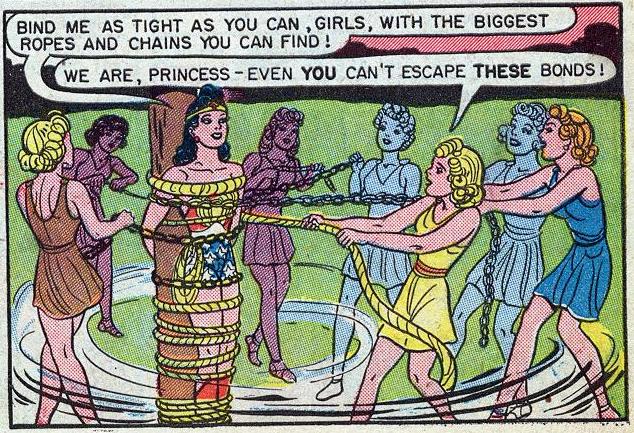

Even a casual glance at the original Wonder Woman issues elicits curiosity, if not alarm, as they depart from the standard procedure of most superhero work. The forties Wonder Woman comics featured a great deal of bondage, and a cavalcade of sexual reversals. Many villains are introduced as one gender, and then transform into or are revealed to be another. Occasionally their gender identity is never fully resolved. Wonder Woman binds enemies with her magic lasso, which makes them obedient to her will, but only after being bound and made helpless herself. The male protagonist, Steve Trevor, repeatedly injures himself, begins the series comatose, and is at points slung over the shoulder of a villain and kidnapped, yet he is never portrayed as being dithering or pathetic. Marston and Peter obsessively repeat classic melodramatic scenarios of bondage and hysterical emotion, while constantly changing who is doing what. This fetishizes the action, blends characters like a Venn diagram, and causes the linear narrative to coil in on itself, disrupting the temporal logic.

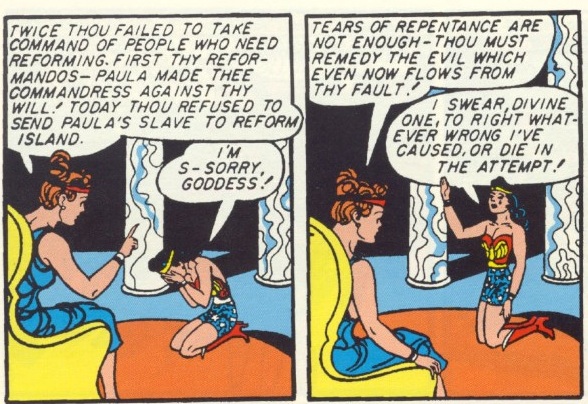

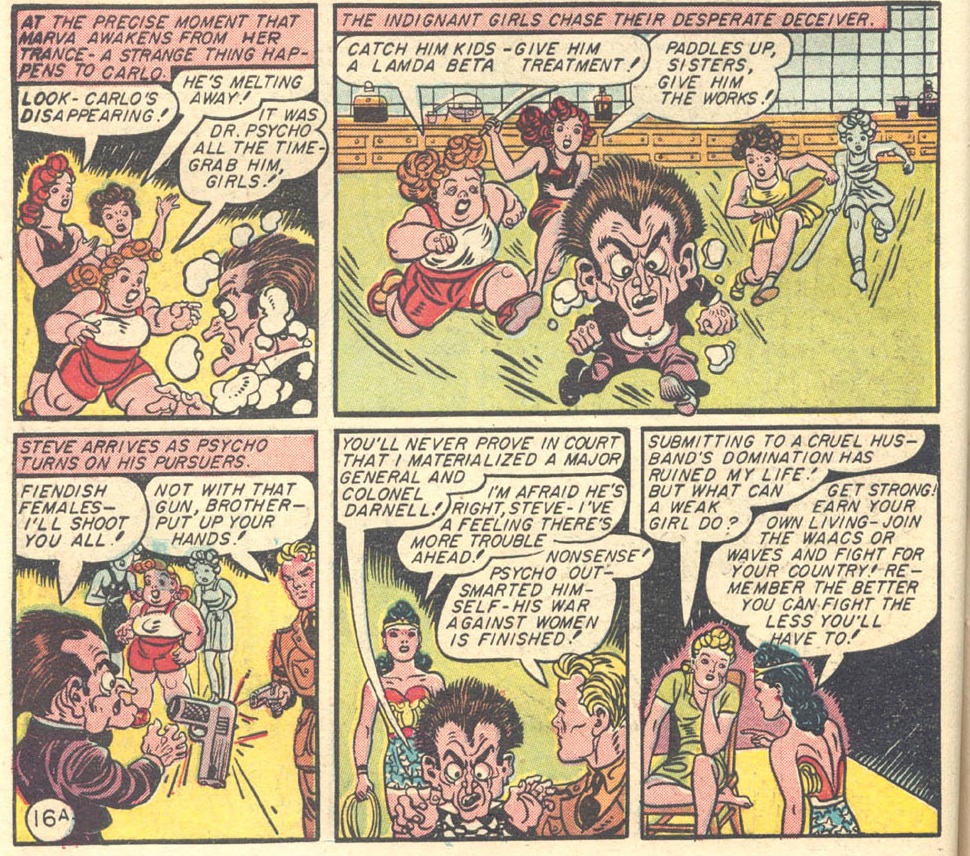

This entanglement allows all characters to participate in what Marston called the two “normal, strength-giving emotions” of inducement, or dominance, and submission, Marston’s key to a happy ending. An eminent psychologist of his time, Marston theorized that the world would be a better place if people learned to accept and practice both dominance and submission, as opposed to harshly overpowering others. Neither dominance nor submission was considered the superior state, and Marston links both in a pleasurable, loving cycle that ultimately leads to world peace.

Yet Marston and Peter don’t let the confounding cycle of bondage continue forever; Wonder Woman ultimately re-educates the villains, sometimes impressing the importance of love-leadership (and being sexually dominant,) on oppressed female characters. Marston intended Wonder Woman to be the model of female leadership. She is boisterous, positive, friendly and even-keeled– an athlete, adventure lover, caretaker, and confident romantic. Wonder Woman throws herself into the fray of battle one minute, while openly crushing on and nursing a wounded Steve Trevor the next. Marston saw no contradiction in these actions, nor in Steve’s vulnerability and strength. Wonder Woman anticipates the multi-dimensional “strong” female characters found with greater frequency today, although this chain was broken by decades, where Wonder Woman was treated like a glorified pinup.

Noah’s book resuscitates these largely forgotten, original comics by examining them as carefully and closely as they deserve, and by meeting Marston and Peter’s work on its own terms. Noah matches the recursivity of the comics with an interweaving analysis of Marston and Peter’s three major concerns: “feminism, pacifism and queerness—or, if you prefer, bondage, violence and heterosexuality.” As Noah explains, “For Marston, these topics were all inextricably intertwined… the book presents not so much a linear argument as a braided exploration, in which the same ideas and obsessions recur in slightly different formations and slightly different perspectives.” As not being strictly formal opposites, bondage and feminism may be the least intuitive pair of the bunch; fortunately, Noah starts there.

Noah argues that the comic’s sexualized fixation on disempowerment, binding, abuse, and manipulation resonates with women and girls, who have been traditionally disempowered in patriarchal society. The representation of subjugation matters as much to women as denunciation of it, (and possibly more,) an idea Noah supports through the theories of several respected literature and media scholars. The Marston/Peter comics have been criticized for eroticizing the bondage of women for a male audience, although Marston’s writings show that he deliberately geared the comics to be read by children of both genders, and at least some evidence indicates they were. Marston and Peter also turn bondage on its head, displaying male victims and female abusers. Noah makes the case that readers simultaneously desire and identify with both men and women, victims and abusers, which highlights a peculiar, and radical piece of Marston’s vision: he denounced rape and abuse as the greatest of evils, but preached the healthy pleasures of reciprocal, consensual, bondage. “Marston, [assistant writer] Murchison, and Peter want to provide these pleasures to everybody, even, or perhaps especially, to the most oppressed and the most wounded.” Noah writes, “That remains a rare ability and an extremely precious one… We can condemn child abuse or we can acknowledge children’s sexuality, but we have enormous difficulty doing both at once.”

Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism… also articulates what is problematic about Marston’s theories, often bringing dissenting voices into the mix. Noah largely supports and expands upon Marston’s ideas with a diverse range of supporting sources. This is brave, especially when Marston casually reconciles themes that many consider mutually exclusive. The chapters on pacifism and queerness contain many theoretical surprises, including alternative visions of the proper functioning of education, motherhood, and sexual orientation. Noah also contributes great ideas of his own. His exploration of gendered responsibility and heroism, and how expectations change for female characters, is both inspired and concise, and hopefully destined to enter into wider discussions of superheroism. Best of all, Noah does a great job of showing that these ideas clearly appear in the Wonder Woman comics themselves, and are not projected onto it by later minds.

Marston didn’t shy away from advocating a new world order ruled by a new order of women, and he casts the net of his imagination widely. Noah does well to bring a wide variety of scholars from many disciplines, tackling each component of Marston’s broad vision piece by piece. Occasionally, this diversity scatters the argument. Readers may question why Noah includes some voices, and not others: he extensively draws on Anne Allison, a scholar of post-war Japanese domestic life, and even then, on a very limited spectrum of her work dedicated to mother-son incest urban legends, (and a bit about lunchbox making.) Allison’s observations parallel the Wonder Woman comics in interesting ways, but an example of ‘matriarchal rule’ closer to the comic’s original context might have served better. I would have also appreciated a second, corroborating source. On the same note, is Pussy Galore the only available example of male fantasy lesbianism? Her significance to the discussion of Wonder Woman’s homosexuality feels both sketchy and undeserved. The most egregious cameo would be Luce Irigaray’s The Sex Which Is Not One. No matter how well her ideas match the argument, statements like “woman has sex organs more or less everywhere,” will seem anatomically preposterous to many, especially when left to float outside a considerate introduction to her work. Distracted by moments like this, a skeptical reader could disengage from the greater point.

My chief criticism of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism is that there should have been more evidence from indisputably relevant and more general sources, and the argument should have relied less on isolated examples. Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism is not a case for the application of Marston’s ideas, as much a case for their remembrance and relevance, particularly within comics and feminist scholarship. As the book stands, Marston’s ideas, freshly unearthed, may be unfairly vulnerable to re-burial, simply because of missing or dismissible evidence.

This would be tragic, considering that Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism illustrates the terrible stakes in making Wonder Woman the afterthought of DC Comic’s line. Noah details two contemporary runs of the Wonder Woman comics, one disturbingly anti-female, the other well-meaning but inane. I would have appreciated a run-down and time-line of the character’s entire development, particularly George Perez’s re-launch of the character in the mid eighties, as Noah goes against the grain in labeling it as trivializing. I would have also liked a discussion of why, after the close of WWII, Wonder Woman repeatedly targets imaginary misogynist dystopias, often on alien planets. The forties run seems equally split between war-propaganda and planetary colonization, and this schism seems rich for exploration. Most of all, I felt the book skipped over an examination of early twentieth century melodrama. Was Marston’s obsession with bondage an exaggeration of existing bondage tropes, sawmills, train tracks, and all, that filmmakers repeatedly inflicted on the female daring-doers of popular cinema? How much of Wonder Woman comes from The Hazards of Helen?

These criticisms essentially come down to a wish the book had been longer, which I realize is a backwards compliment. I wish this because I too am convinced that the Marston/Peter Wonder Woman comics are relevant today. People love superheroes, perhaps now more than they ever did. The current popularity of superhero entertainment has lasted longer than their initial explosion in the forties. I hope there is room in mainstream entertainment for risky visions of what it means to be a hero. Even more, I hope there is room for visions like Marston’s, who was willing to embrace paradox, and attempted to describe the wonderful, ineffable, irrationality of love.