Last week I wrote about an old Hulk comic in which our green protagonist crushed a female artist who wanted to appropriate him for her gallery, proving that comics are virile and manly and can kick Lichtenstein’s effeminate posterior.

So Hulk wins the battle against high art there…but in comments, Ng Suat Tong pointed me to another tussle where the victory is not so assured.

That’s “Hulk (Wheelbarrow)” a sculpture by Jeff Koons.

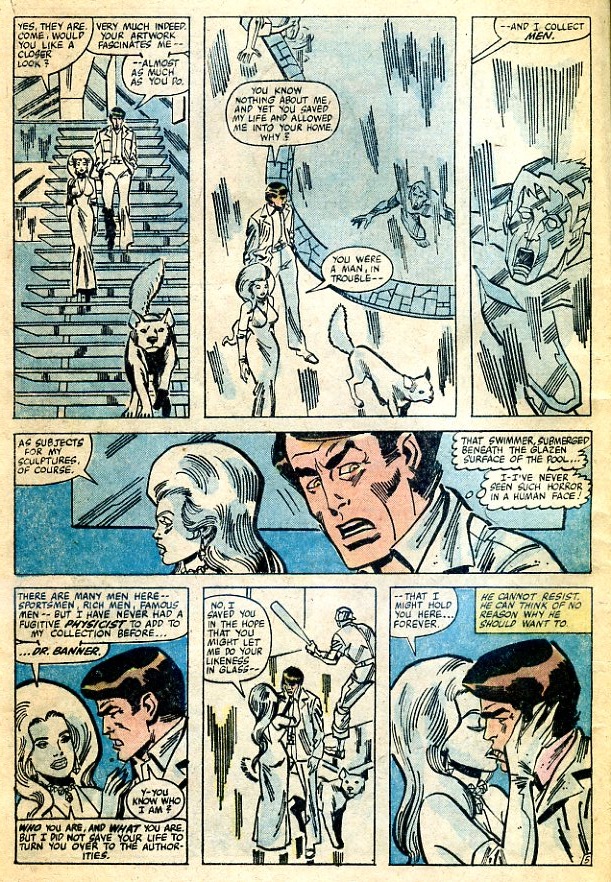

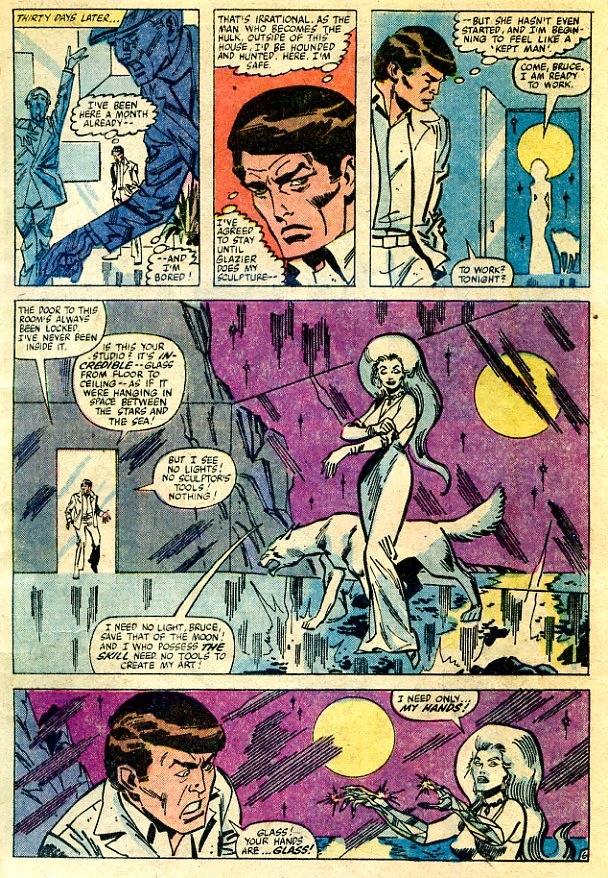

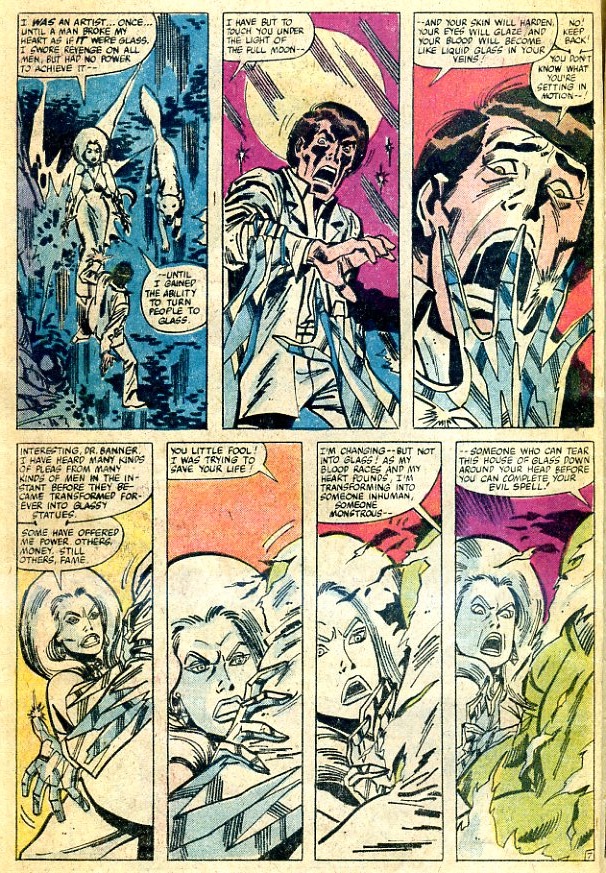

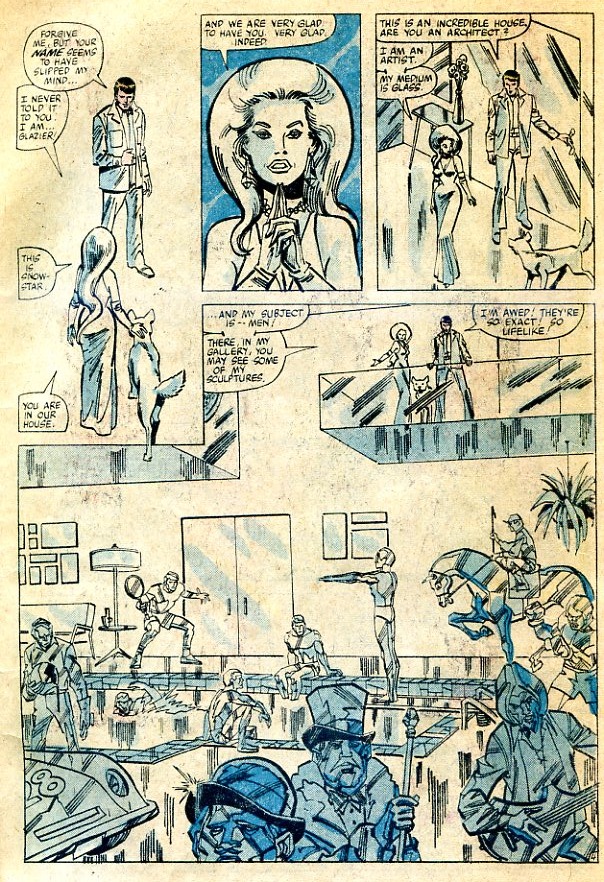

When I suggest that Koons has here defeated the Hulk, I mean that literally — at least in terms of the narrative of the comic I discussed last week. Again, in that issue, Bill Mantlo and Sal Buscema presented us with an evil temptress/Circe/high artist who turned her male victims into glass. She intends to do the same to the Hulk, and keep him forever in her gallery as a glass sculpture. Hulk is too big and green and pulpy to succumb to her blandishments, whether they involve sex, magic, or the granting of high art validation. So he destroys her and her house and escaped. And then, 20 odd years later, Jeff Koons gets him and puts him in a gallery anyway.

The trasformation is a little different though. Hulk isn’t turned into graceful, fragile, feminized glass. He’s a plastic inflatable — a giant toy. The act of transformation, then, is not actually transformation — it’s simply relocation. Putting the infantile, virile Hulk in a gallery turns him, instantly, into refined prettified high art, with flowers. Koons’ assault on Hulk is even more cruel and insidious than the villainnesses. The glass Circe, at least, felt that Hulk had something she wanted; she acknowledged the value of his virility by wanting to touch it with her glass creating hands and make it her own. But Koons doesn’t even have to make Hulk his; he just has to pick him up and put him in his place. If there’s any value in Hulk, it’s not in his strength, but in his ridiculousness and incongruence. He’s cheap, plastic ephemera. His incongruous worthless is his worth. He’s not a totemic real to be stolen; he’s just a ridiculous prop to be mocked.

Or so you might think. In fact, though, the Hulk is not a plastic inflatable. He’s bronze. Koons made the metal statue, then painted it to look like an inflatable. The Hulk is not a piece of plastic crap; he’s a virtuosic sculpture made to look like a piece of plastic crap.

In terms of the comic, its as if the villain had turned Hulk not into glass, but into an exact replica of the Hulk indistinguishable from the original. Except secretly made of glass. Or, for another comic-book analogy, you might remember the Harvey Kurtzman Plastic-Man, in which the imposter Plastic-Man is accepted as the real Plastic-Man since anything made out of plastic is fake. By that logic, Koons’ imitation plastic Hulk is more real than the real thing, since a kid’s fake plastic Hulks (in comics or outside them) are the real ersatz thing. Or, to put it another way, the Hulk in the gallery, by virtue of recognizing the fakeness of the Hulk in the comic, is more real than the original.

In Harold Bloom’s terms, Koons’ is a “strong” reading of the Hulk. Geoff Klock in How To Read Superhero Comics and Why points to writers like Frank Miller as “strong” rewriters, troping against the accretion of supehero continuity, so that the Dark Knight becomes, in some sense, the only Batman, “‘the powerful reading that insists on its own uniqueness and its own accuracy….[Miller] compels us to read as he reads, and to accept his stance and vision as our origin.'” Where Miller makes Batman more real and powerful and cool and coherent, though, Koons’ strong, bronze reading of Hulk is parodic. The metal Hulk insists on the actual Hulk’s transient blow-up crappiness. The amazing virtuosic reproduction of pop detritus emphasizes that it is detritus. The amount of genius and talent that Koons has put into his Hulk deliberately underlines the hackish ineptitude of Mantlo and Buscema. They ineffectually try to reproduce high art; Koons methodically and perfectly reproduces low art. There couldn’t be a much more devastating demonstration of the justness of that high-low hierarchy.

Or that’s one way of reading it, anyway. It’s worth pointing out, though, that Harold Bloom would really probably hate Jeff Koons, and vice versa. You can see Koons here as parodying the Hulk by employing the virtuosity of high art, but you could just as easily see him as employing the Hulk to parody the virtuosity of high art with its cult of “strong” Bloomian artists. Or, for that matter, you could see him as simultaneously parodying both; the serious metal sculpture disguised as a kid’s blow up doll seems to implicate both the Hulk’s hyper-masculine worship of physical power (via the ridiculous big green muscles) and the traditional art world’s hyper-masculine worship of genius (via the ridiculous virtuosity and heaviness.)

For Koons, then, high art and low art aren’t opposed. Rather, they’re both engaged in the same project of constructing a powerful ersatz masculinity — the dream of inflatable muscles made out of bronze. Koons thinks that’s funny. But he doesn’t just think it’s funny. Surely there’s some affection in those (Blooming?) flowers, picked fresh for the exhibit, and placed in a wooden wheelbarrow that is not an inflatable, nor bronze, but simply a wooden wheelbarrow. The superhero and the superartist — beneath all that roaring and posturing, they just want to give you pretty things. In the gallery or on the comics page, when Hulk smash, it means “I love you.”