There were a lot of great story arcs written during the Silver Age of Comics, which most comics historians agree spanned the years 1956-1970. But the best one, in my opinion, “If This Be My Destiny,” was published as a three-part story in “Amazing Spider-Man” issues 31-33, cover-dated December 1965 through February 1966.

But before we can analyze exactly why the story was so special, we first need to identify who the key player was in its creation, layout, pacing and overall story.

Stan Lee was attributed as the “writer” of the story in the credits, but he, as I discuss below, had nothing to do with the story arc’s creation. For while he wrote the dialogue after the pages were laid out and drawn, he did none of the plotting, and had zero input on the pacing, basic character interaction, mood, and story direction. All of that was done by artist Steve Ditko.

The “Marvel Method” of creating comics during this period was peculiar in that regards, especially for Lee’s top bullpen artists Ditko and Jack Kirby. When the process was first implemented by Lee in the early 1960s – ostensibly to save him the time of writing a full-blown script – he and the artist of a particular comic book would have a story conference, work out a plot, and the artist would go home and draw out the entire issue. The finished pages would then be given to Lee, who proceeded to add the dialogue.

But by the mid-1960s, Kirby and Ditko were so good at creating and plotting stories that Lee himself admitted in a number of interviews that he often had little or no input for story arcs. In fact, he often would have no idea what the story for a particular issue was going to be about until after the pages were delivered by the artist.

Lee himself details this Marvel Method process in an unusually candid interview he did for “Castle of Frankenstein” #12 (1968), a magazine that covered popular culture from that era:

“Some artists, of course, need a more detailed plot than others. Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s make the next villain be Dr. Doom’… or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He’s good at plots. I’m sure he’s a thousand times better than I. He just about makes up the plots for these stories. All I do is a little editing… I may tell him he’s gone too far in one direction or another. Of course, occasionally I’ll give him a plot, but we’re practically both the writers on the things.”

This was also true with Ditko and his early Marvel Method process on “Amazing Spider-Man.” He and Lee would have a story discussion, after which Ditko would leave, pencil out the story and then, inside the panels, write in a “panel script” (suggested dialogue and narration). He would then bring the pages back to Lee and they’d discuss the story from start to finish. Ditko would annotate any changes outside of the panels, and then he’d leave the penciled pages with Lee. Lee would then write in the final dialogue and the book would be lettered. Ditko then picked up the lettered pages, and made any of the annotated changes during the inking process.

But Lee really had no long-term vision for Spider-Man. He never thought about what he would do with the characters from one issue to the next. He’d just say, “Let’s make Attuma the villain,” and Ditko would have to talk him out of it. The glue that really held the Spider-Man direction and continuity together in those early days of the character was Ditko.

Over time, Ditko received more and more story autonomy and character development latitude that by about issue #18, he was doing the sole plotting chores with no input from Lee. But it took time for Lee to give Ditko what was then unprecedented plotting credit, beginning with “Amazing Spider-Man” #26 (July 1965), and ending with Ditko’s last issue, #38 (July 1966).

As with many aspects of those murky creative days at Marvel, Ditko’s credits raise questions. For example, why did Lee agree to give Ditko plotting credit, but not Kirby, whose “Fantastic Four” and “Thor” plotting autonomy was apparently quite similar? And why did Lee, when he finally did start giving artist and plotting credit to Ditko, suddenly, after one issue, expand his own credits from “writer” (his standard credit line for the first 26 issues of “Amazing Spider-Man”) to both “editor and writer”?

Around the time Ditko began receiving plotting credit, a rift between the two arose and, according to several Marvel staffers, was so acute, Lee would not speak to Ditko. It was during this year-long communication blackout period that Ditko wrote his Spider-Man magnum opus, “If This Be My Destiny.”

Additional evidence that Lee had no story input during this period can be found in “Amazing Spider-Man” #30, which set the stage for Ditko’s historic three-issue story arc. In that issue, the villain is a thief named The Cat, but Ditko also introduced, in two different parts of the story, henchmen for The Master Planner – the surprise villain for the “Destiny” story arc that was to start in issue #31. Yet because communication between Lee and Ditko had ceased, Lee had no idea who the costumed criminals were and misidentified them as The Cat’s henchmen – which, upon close examination of the story, makes no sense. It’s not until the next issue that the error becomes obvious to Lee and he gets a better grasp of Ditko’s storyline.

So, now that we have a better understanding about who created what for this historic story arc, exactly what is it that makes Ditko’s “Destiny” so great from both a literary and artistic standpoint?

How does one go about measuring greatness? After all, there are no established standards for greatness in comics, or, for that matter, the two creative disciplines that are merged to create them: art and literature.

Some argue that great art or literature is timeless, and that it appeals to our emotions in a compelling and riveting way. Others argue that it is something that breaks new ground.

Ditko’s three-issue story arc easily accomplishes all three, and a lot more.

We can glimpse Ditko’s personal, objective views about what constitutes art from his recorded statements for the 1989 video, “Masters of Comic Book Art.” Ditko said that based on Aristotle’s Law of Identity, “Art is philosophically more important than history. History tells how men did act; art shows how men could, and should act. Art creates a model – an ideal man as a measuring standard. Without a measuring standard, nothing can be identified or judged.”

It’s clear to me that Ditko, through his stories and art in “Amazing Spider-Man,” was striving to do just that: mold Peter Parker/Spider-Man into a positive heroic model.

Throughout his career, Ditko has always been a creative, experimental, thinking-man’s innovator. It was evident in his costume designs, character portrayals, settings, lighting, poses, choreography, etc. – literally every aspect of the comic book creative process. For example, no one before or since has created anything like Ditko’s multi-dimensional worlds for his Doctor Strange character. And his creative depictions of Spider-Man’s costume, devices, movement through space, and overall look set the standard for every single Spider-Man artist who has followed. I’ve been a fan of his work for 45 years, and to this day, I still marvel at how Ditko was able to take the totally fantastic and make it seem like it could actually be real.

Ditko was innovative in other ways as well. Unlike many of his contemporaries back then, Ditko had an eye on continuity, and started meticulously planning story arcs and sub-plots many months or even years in advance. Such was the case with his slow and methodical development of the Green Goblin‘s secret identity over a multi-year period, and his tantalizingly slow introduction of Mary Jane.

Ditko’s development of his “Destiny” story arc in “Amazing Spider-Man” #31-33 was no different. Ditko planted the initial seed for the arc way back in issue #10, when Peter Parker provided blood during a transfusion of his seriously ill Aunt May. As regular readers eventually found out, Parker’s selfless act of kindness turned out to be a ticking time bomb for his frail aunt, who began suffering ominous fainting spells in issue #29, and again in issue #30.

As I mentioned above, the mature, heroic side of Peter Parker and Spider-Man had been building for many months before the “Destiny” story arc kicked in – a steady drumbeat that would soon reach a deafening crescendo. At the same time, Parker was enduring important emotional lows and highs. For example, his long relationship with Betty Brant had been pulled wire taut in the months preceding “Destiny,” and was at the breaking point. Likewise, Parker graduated high school in issue #28, and was about to go off to college and enter what he hoped was a new and exciting chapter of his life. But despite his emotional roller-coaster rides, it was clear to the regular reader that Parker was growing more mature, determined and focused both as a normal person and as Spider-Man. He was no longer the silent doormat for his boss, J. Jonah Jameson, his high school nemesis Flash Thompson, or any other negative influence in his life.

It was at this convergence of events where “Destiny” began, and the reader soon found out just how mature, determined and focused Parker and his alter ego would be under the most harrowing of circumstances – circumstances that would have the highest emotional stakes imaginable for the character.

As the three-issue story arc opened with issue #31, the stage is set for what’s to come when Spider-Man stumbles across the Master Planner’s men fleeing, via helicopter, a location where they have just stolen some radioactive atomic devices. A battle ensues, but they escape. It is during this escape that the Master Planner’s underwater refuge – a key location later in the story – is revealed.

The scene shifts to Peter Parker’s home, where he waves goodbye to his Aunt May before heading off to his first day of college. The reader can see that she is gravely ill, but she’s doing her utmost to hide it from her nephew so he doesn’t worry. When Peter returns later that day, she can hide it no longer and collapses in his arms. Her illness is so serious, their family doctor admits her to a hospital. Peter is by her side until she falls asleep, and heads for home. Here the emotional roller-coaster starts its journey again as Peter tries to juggle college, lack of sleep, mounting bills, and Aunt May’s illness all at the same time. But Aunt May’s illness overshadows everything else and his new classmates find him aloof and distant.

As his money pressures mount, Peter changes to Spider-Man so he can look for news photo opportunities around the city – as taking news photos for “The Daily Bugle” is his only source of income. He gets a tip that a robbery will be taking place at the docks that evening, and when he arrives, he once more finds the Master Planner’s men attempting to steal a ship’s radiation-related cargo. Another battle ensues, and they escape again – this time into the water using scuba gear. As the issue comes to a close, an unseen Master Planner, in his underwater lair, mulls how Spider-Man is thwarting his attempt to use radiation secrets for nefarious purpose. But the final three panels are far more ominous: the doctors caring for Aunt May have finished their tests, and conclude that she is dying.

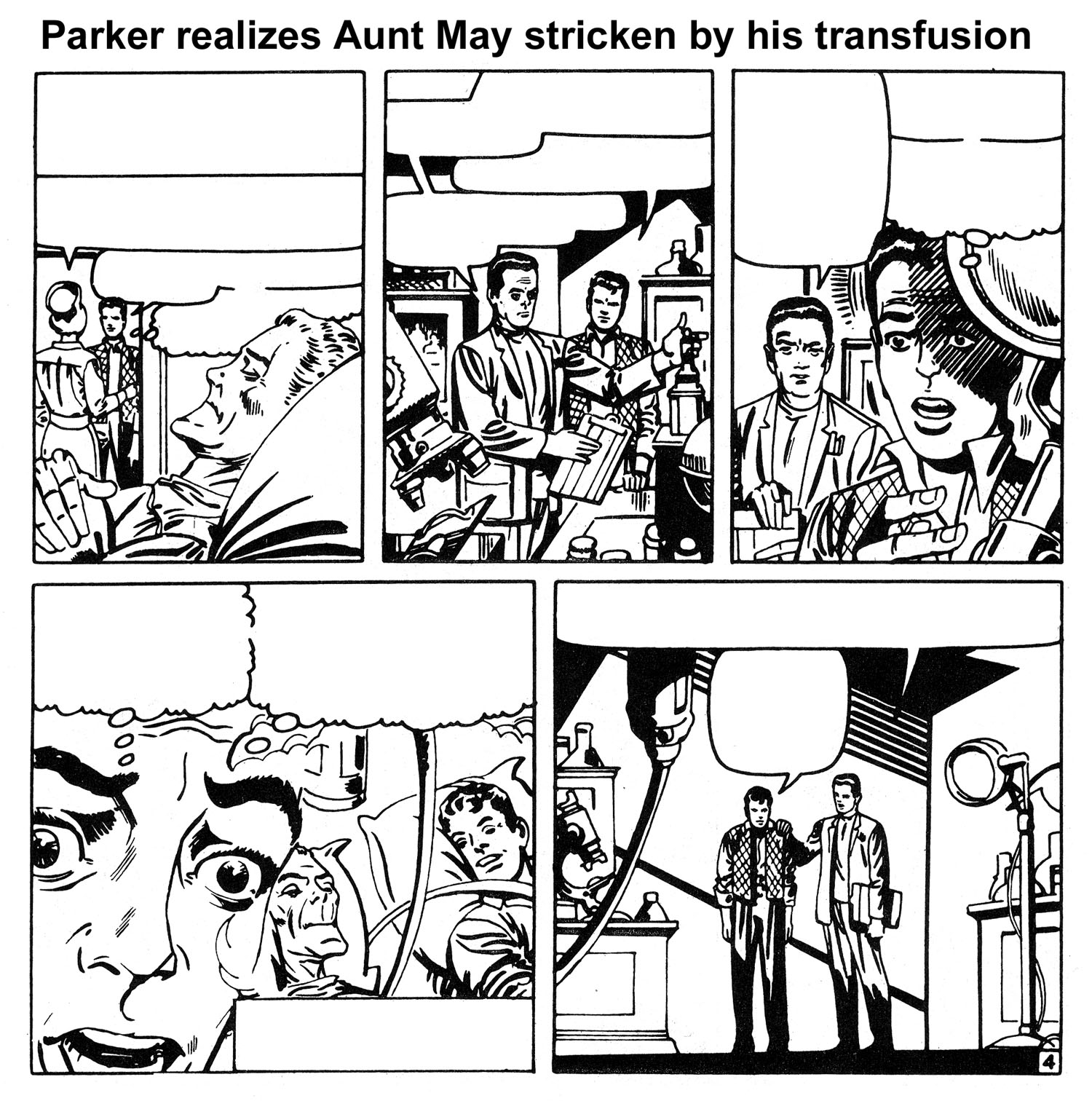

Issue #32, “Man on a Rampage,” opens in the Master Planner’s underwater hideout, and we quickly find out that he is actually none other than Dr. Octopus, one of Spider-Man’s most dangerous foes. The scene then shifts to Peter, whose relationship and money problems keep mounting. But things get even worse when he visits the hospital and the physician attending to Aunt May informs him that her terminal illness is being caused by an unknown source of radioactivity in her blood. Peter immediately realizes that the radioactivity must have come from his contaminated donor blood which Aunt May received during a transfusion many months earlier for a different illness.

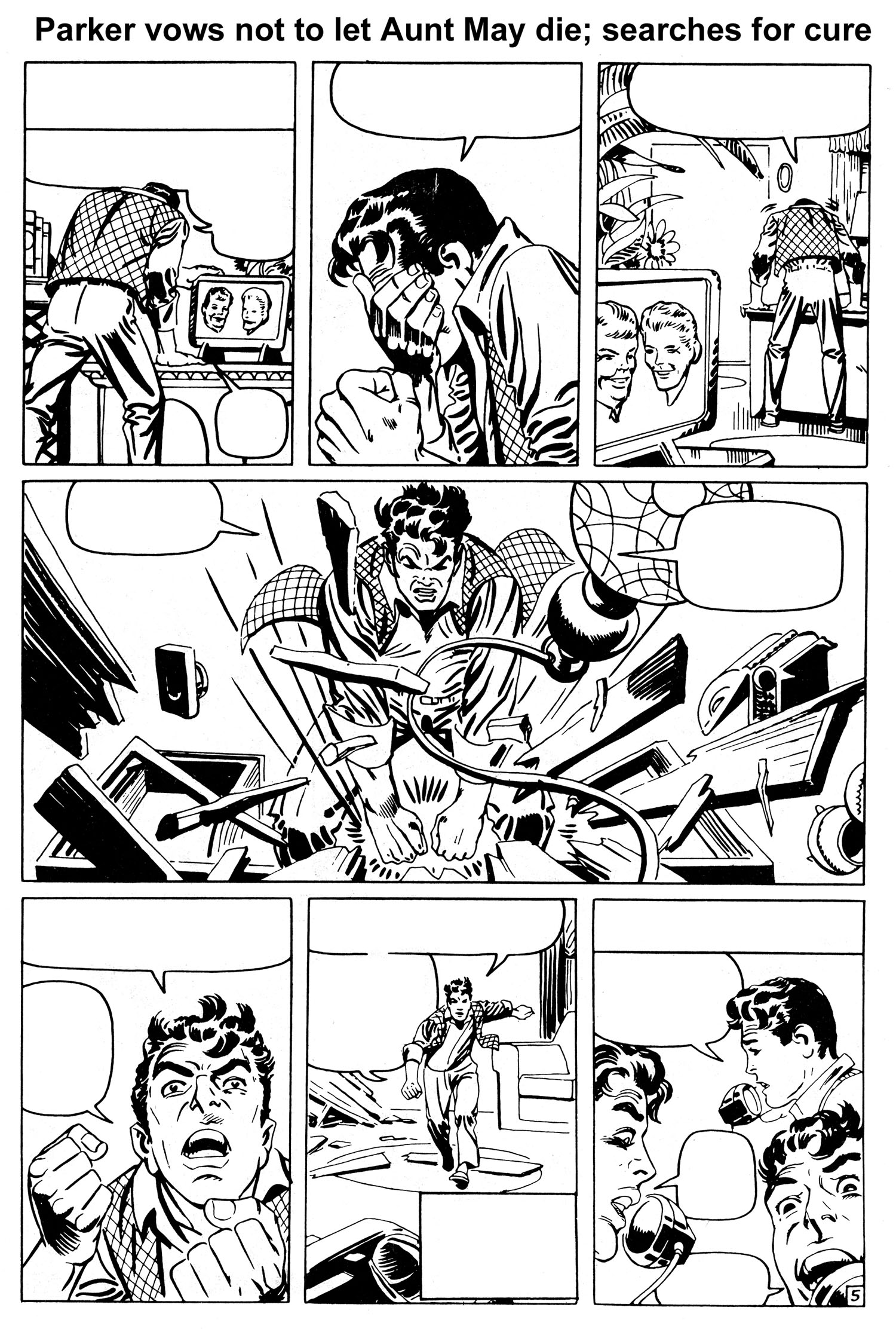

And while the radioactivity is harmless to him, it is having a devastating effect on Aunt May. So not only was young Parker responsible for the death of his Uncle Ben when he first became Spider-Man, he may soon be responsible for the death of Aunt May. This emotional realization is perfectly portrayed by Ditko, along with Peter’s vow that he will not fail at saving a loved one again.

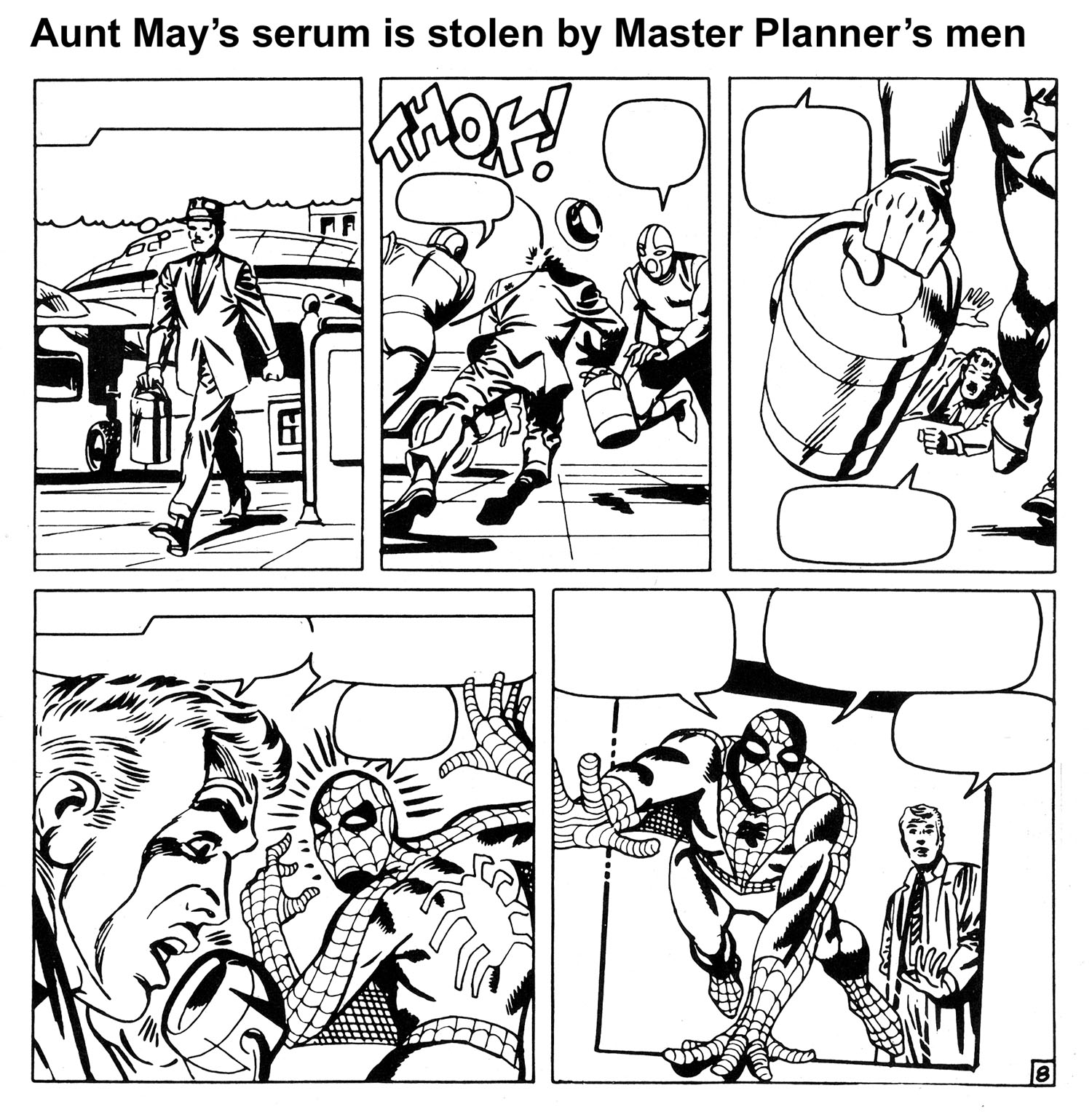

Parker then gets an idea. He tracks down Dr. Curtis Connors (aka The Lizard) – a blood specialist who he hasn’t seen since issue #6 – and, as Spider-Man, gives him a stolen vial of Aunt May’s blood, and begs him to see if he can discover a cure for his “friend.” Connors agrees and after some tests says that an experimental serum called ISO-36 might help – but it will cost money. Parker leaves, hocks all of his personal laboratory equipment, gets the money, and returns to Connors’ lab as Spider-Man. While they wait for every available bit of the rare serum to be express-delivered from across the country, Parker, a budding scientist in his own right, helps Connors with some preliminary lab research. Suddenly, Connors gets a phone call informing him that the ISO-36 was stolen by the Master Planner’s henchmen, and Spider-Man explodes into action.

In an effort to find the precious stolen serum, Spider-Man literally does go on a rampage, snatching up criminals and stoolpigeons, smashing down doors and rooting through every underworld nook and cranny across the city for any possible leads. As the clock ticks, we see Aunt May slip into a coma, Dr. Connors patiently waiting, and a desperate Spider-Man becoming more and more frantic.

Suddenly, after swinging into a blind alley, his Spider-Sense points him to a hidden trapdoor leading to the underground tunnel entrance for the Master Planner’s underwater hideout. Battling through dozens of henchmen, he slips through a sliding doorway into the tunnel. Alerted by one of his men that Spider-Man is searching for the stolen ISO-36, Dr. Octopus decides to use it as bait so he can kill Spider-Man, once and for all.

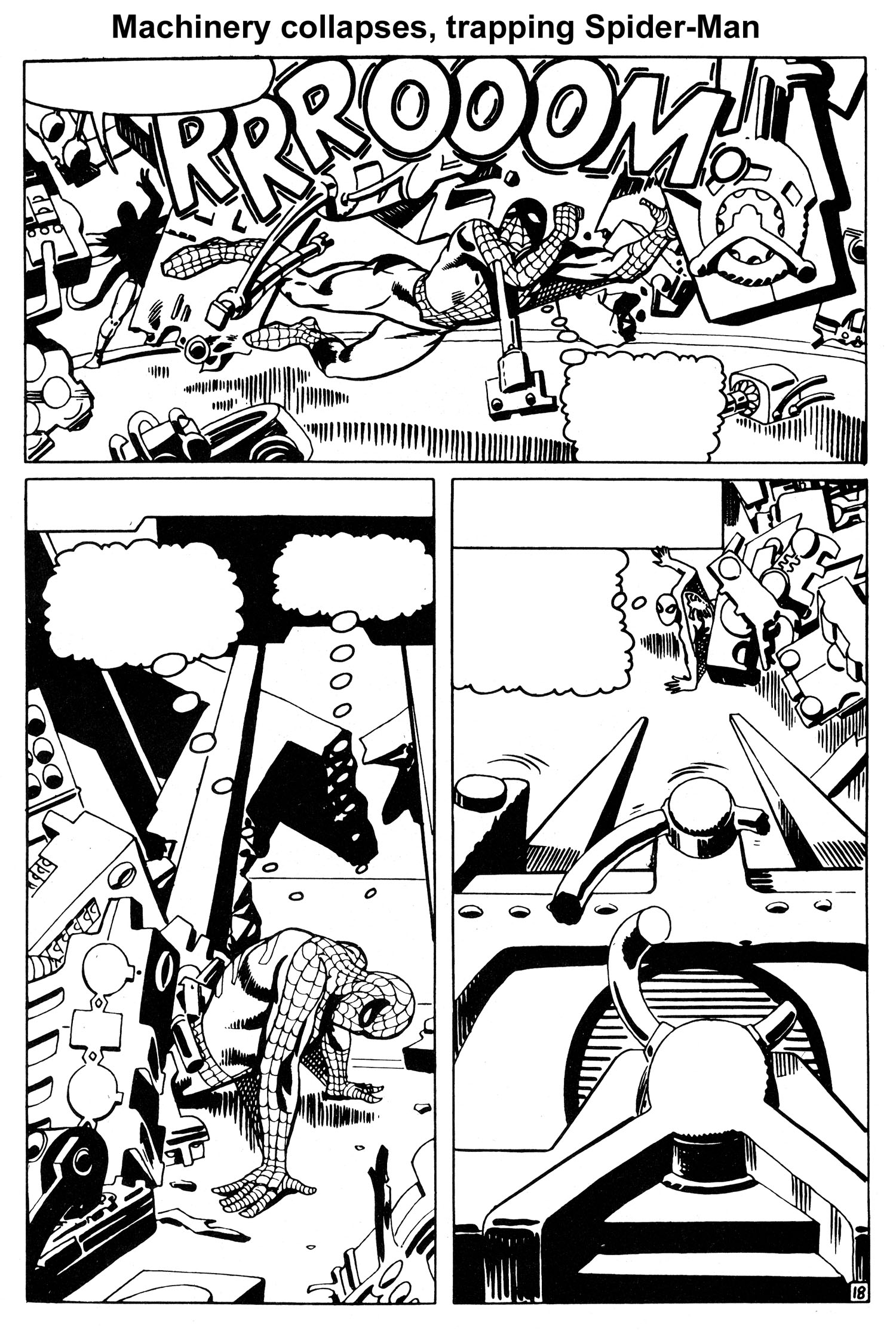

He places the serum in the middle of the cavernous domed main room of his underwater lair, and waits. Spider-Man enters, and despite a last-second warning by his Spider-Sense, the trap is sprung and a raging battle ensues. But Dr. Octopus soon finds out something is different this time, as Spider-Man is fighting like a man possessed. Startled, Dr. Octopus quickly shifts from offense to defense, and within minutes is no longer fighting, but trying to find a way to escape the madman he is facing. A main support beam is shattered during the fight, and as the machinery inside the dome begins collapsing, Dr. Octopus slips away. But Spider-Man is trapped.

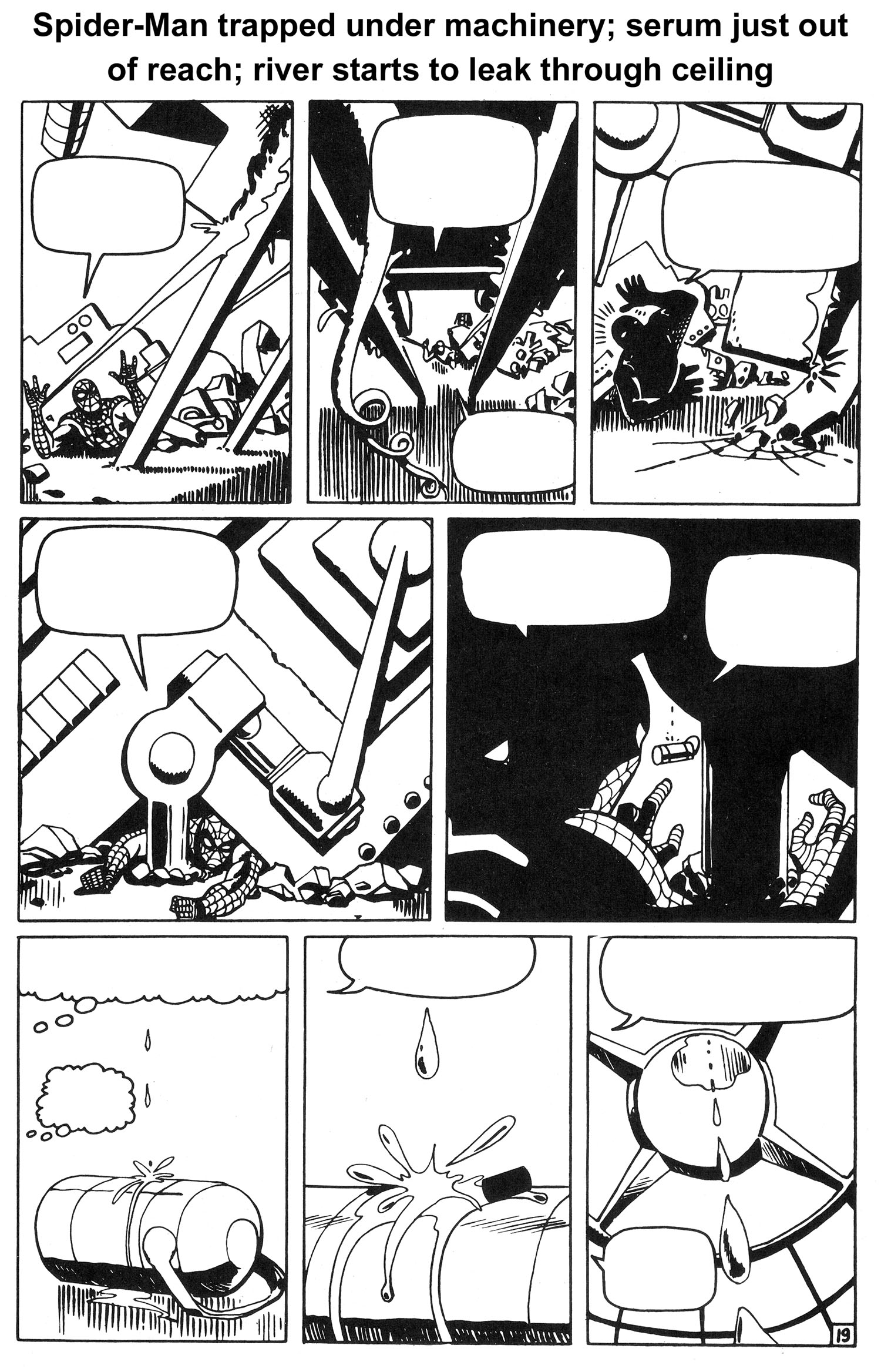

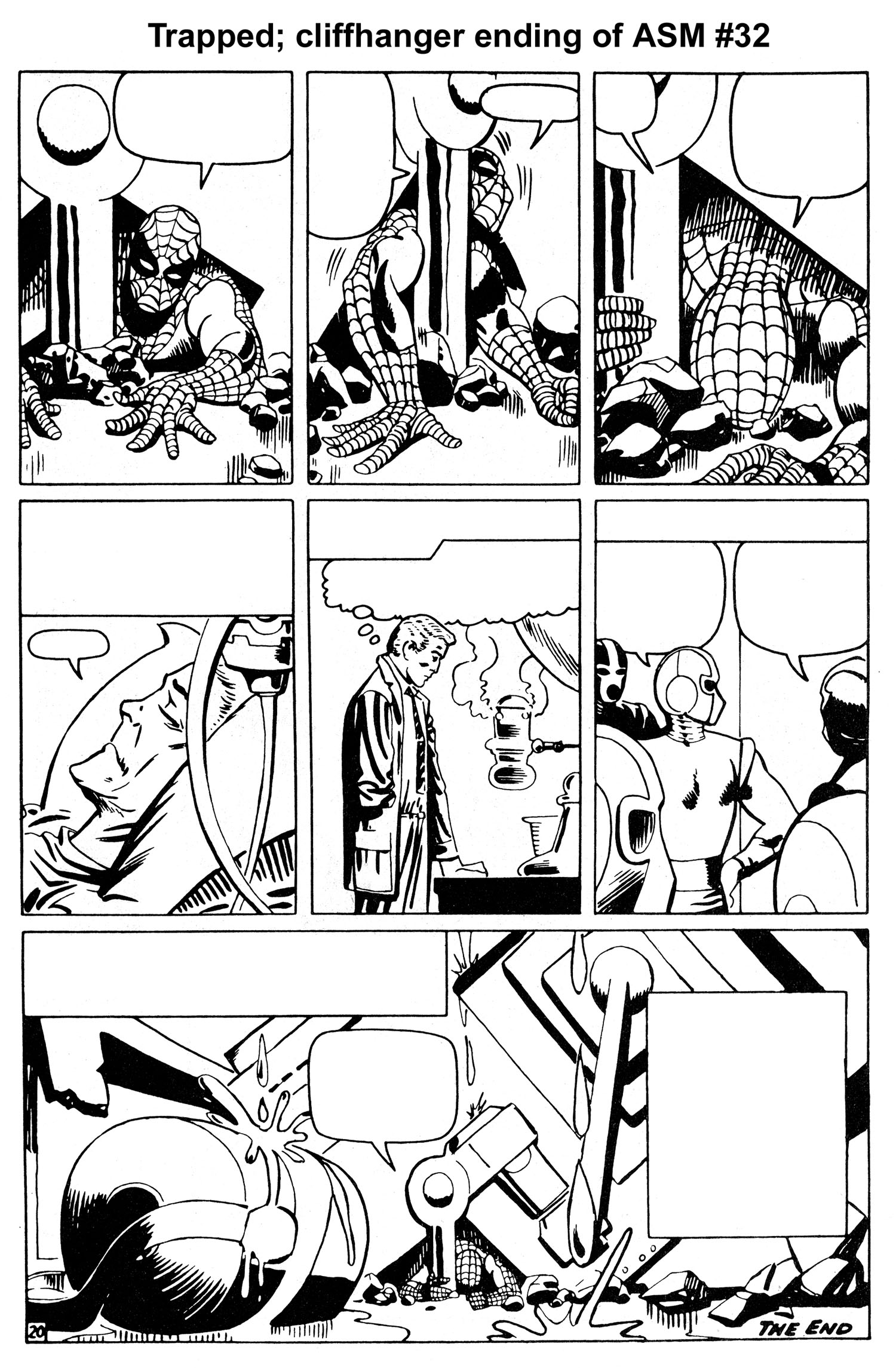

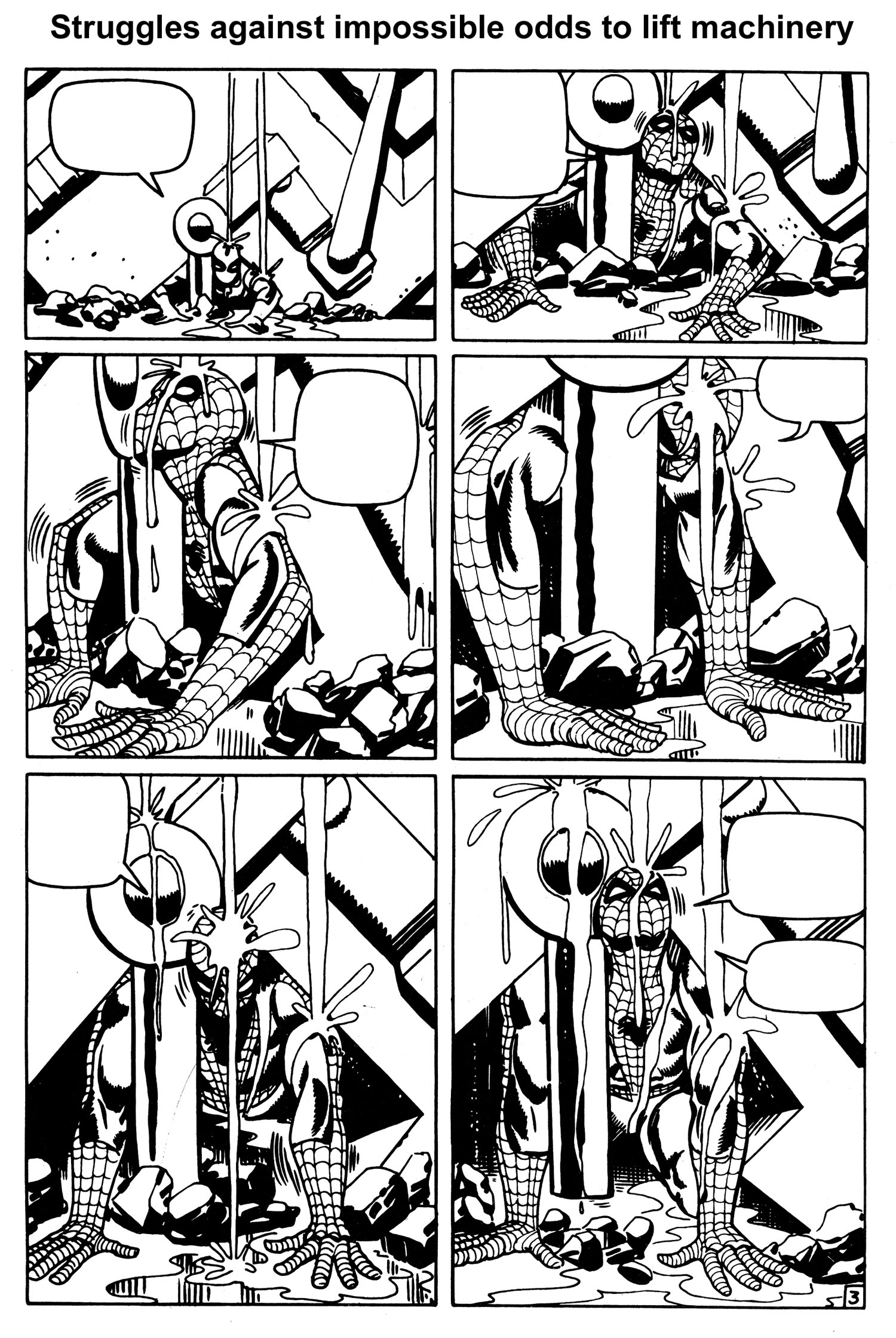

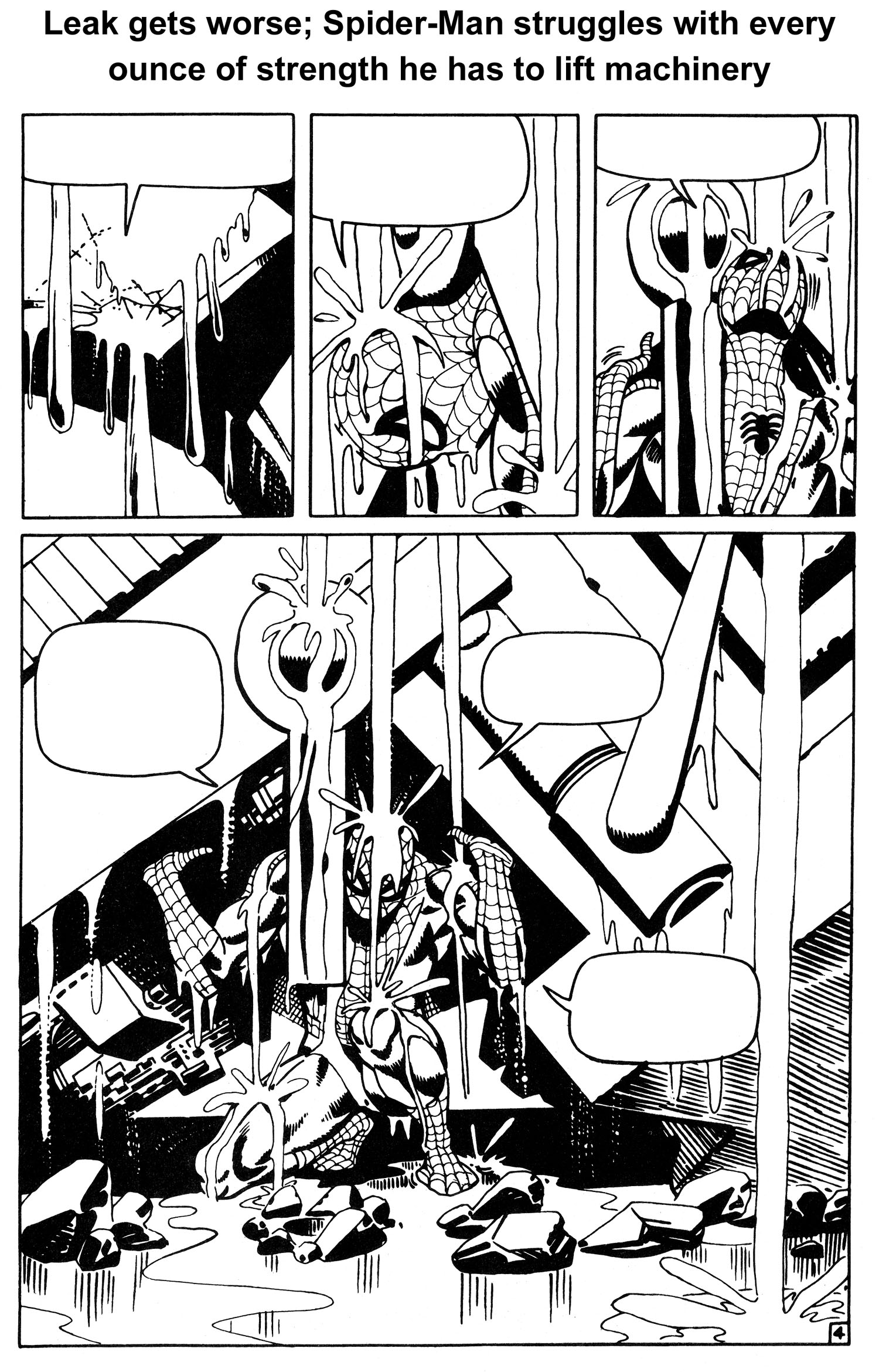

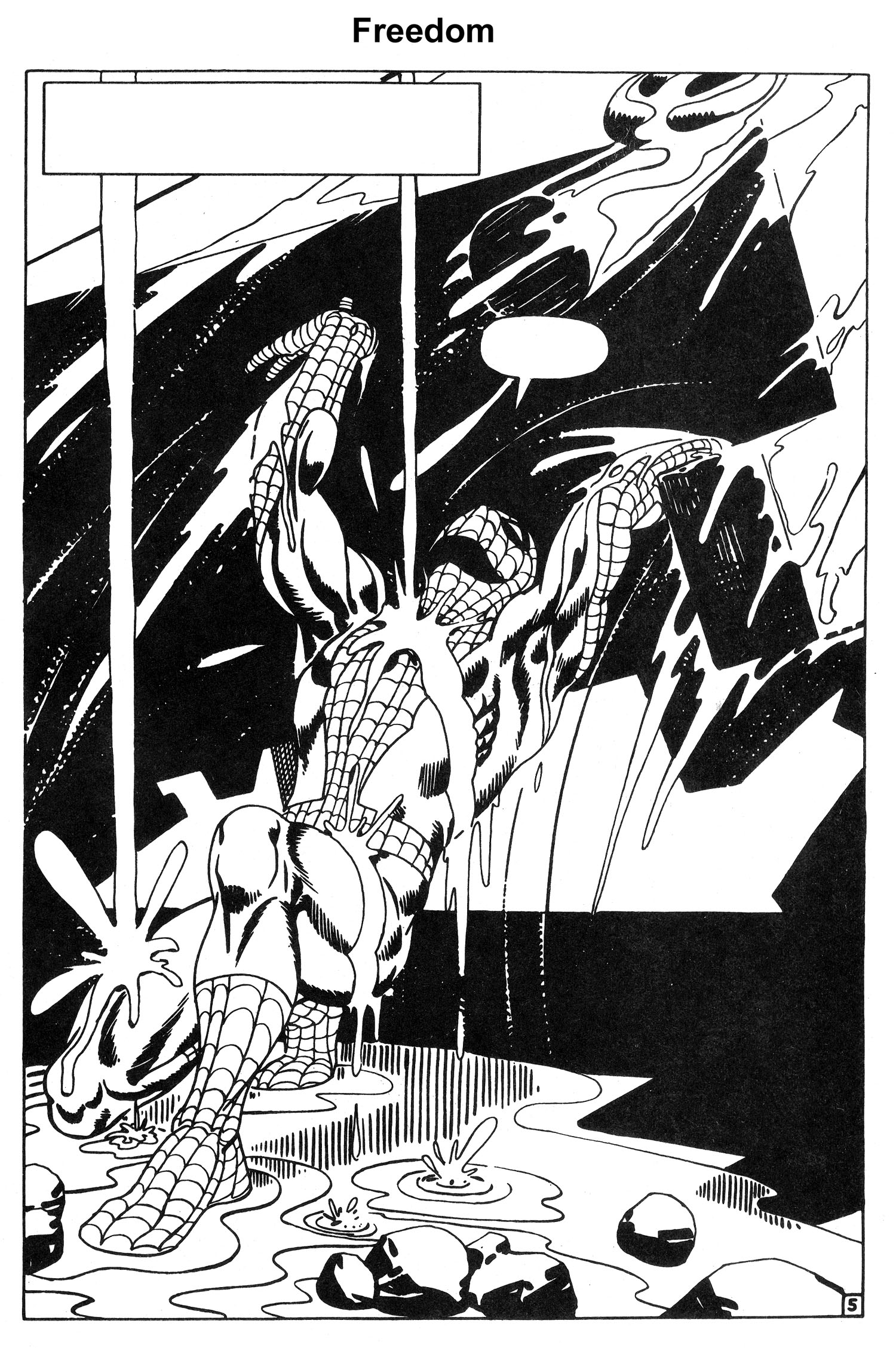

For the last three pages of issue #32 and the first five pages of issue #33, Ditko creates the most masterful bit of sequential art of the Silver Age, and possibly ANY age. It is an artistic tour de force that needs no words to convey the story. The drama, stakes and emotional tension of the main character could not possibly have been wound any higher as issue #32 came to a close. And I don’t think there was a sentient reader alive back then who wasn’t gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen in issue #33.

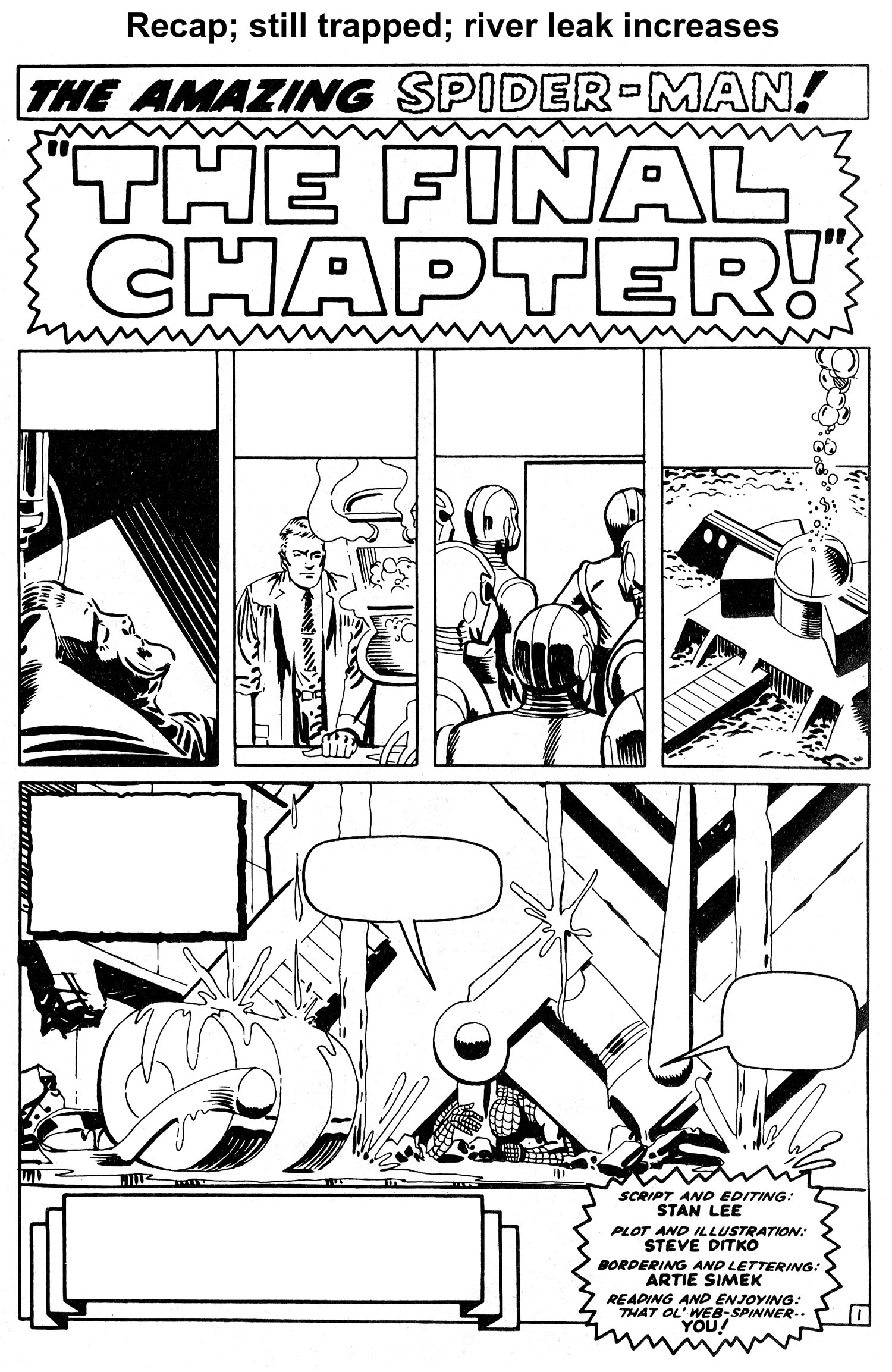

As issue #33, “The Final Chapter,” opens, the powerful visual sequence begun in the previous issue continues. After a four-panel recap, we see a hopelessly-trapped Spider-Man buried under the weight of an enormous mass of machinery as the main room of the underwater hideout of Dr. Octopus begins to flood. Aunt May is dying, and the serum he needs to save her lies on the floor in front of him, just out of reach.

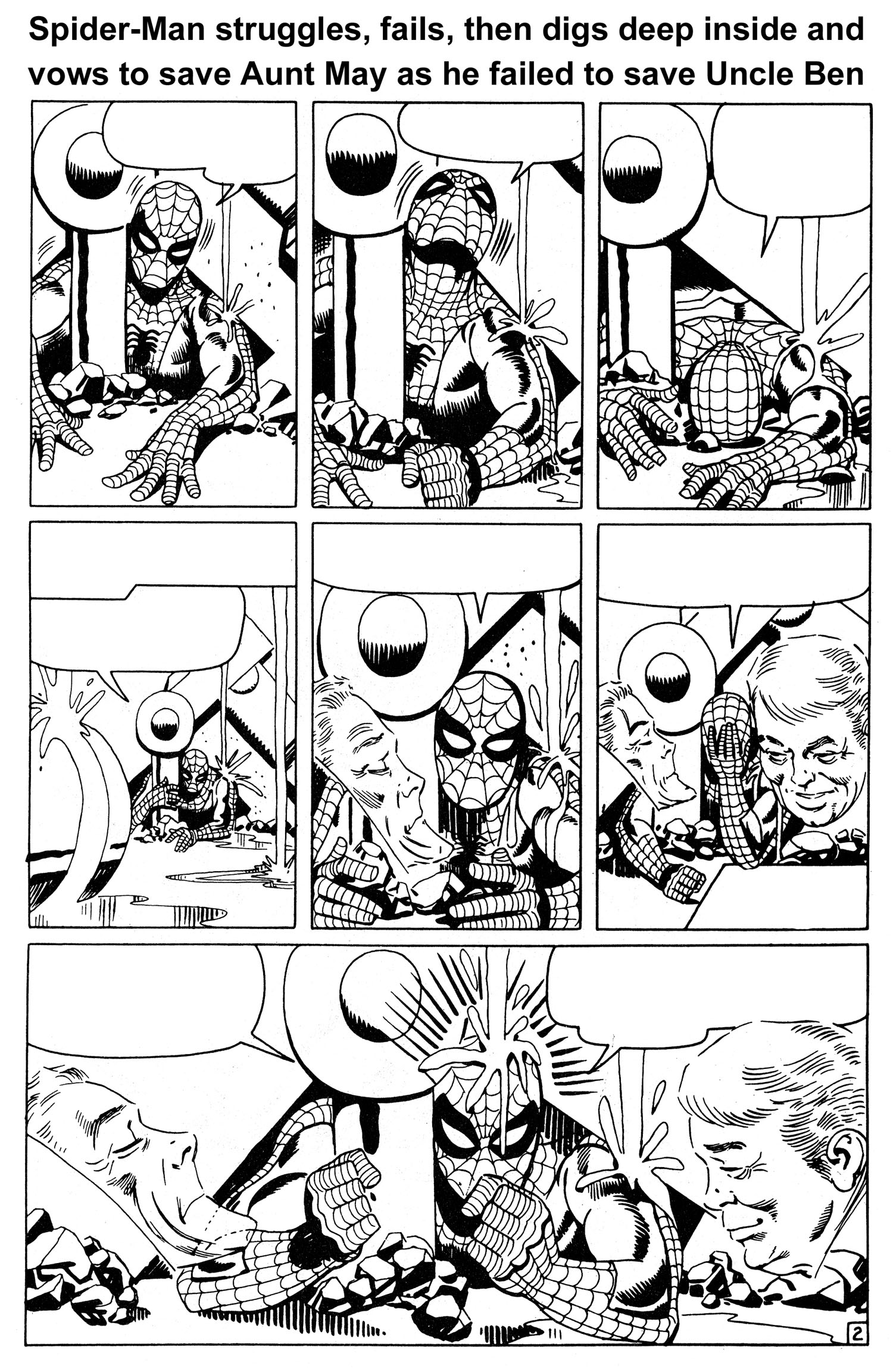

And just when you think it’s over for Spider-Man, and that he’s doomed to die, he once more thinks of Uncle Ben and Aunt May, taps a latent reservoir of sheer will and determination from his innermost being, and attempts one last time to break free. Ditko captures the agonizing struggle pitch perfectly, with sequential pacing that rivals that of the best comic book or film. And with one last mighty heave, he’s free (See Figures 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11).

But Ditko’s not finished. During the next 15 pages, Spider-Man must overcome even more physical and emotional adversity to save his aunt. But I’m not going to spoil the entire story arc. Grab a reprint of issue #33 and finish it yourself. You won’t regret it.

A few final points about the “Destiny” story arc and Ditko’s often underappreciated creativity.

First, the reason I showed wordless versions of the story’s pages was two-fold: to show how visually powerful Ditko’s storytelling abilities were, and to highlight just how crucial artists like Ditko and Kirby were to creating stories using the Marvel Method during the Silver Age.

Second, I want to make sure everyone understands just how much responsibility the artist had back then. In cinematic terms, Ditko not only co-wrote the screenplay, he was the storyboard artist, director, film editor, casting director, cameraman, cinematographer, production designer, costume designer, art director, stunt director, and set designer. Lee, on the other hand, co-wrote the screenplay, and did the “sound” editing.

So, while Lee’s dialogue certainly enhanced the story, Ditko was the creative force behind almost everything else. In that regards, if the story were a Corvette, Lee applied the paint job, pinstripes and some of the detailing, but Ditko designed the car, crafted all the parts, and assembled it.

‘Nuff said!