Some years ago I was asked about the benefits of working in the comics form, as opposed to writing a novel. Since the subject at hand was a graphic novel, that is, with a fair amount of words thrown in the mix, my argument soon devolved into the classic “language vs. image” duality. It went something like this:

Language is a form of communication we use to convey concrete, unambiguous information about the world. When we say “sheep,” we don’t mean “cow,” or “tree,” and we just have to assume or hope that the person we speak to knows what “sheep” means. That is the basics of language, great civilizations have been built on our mutual understanding of words like “sheep”. Of course, once we have more than one sheep, we need to specify whether it’s a ewe, a ram, or a lamb, so we invent those terms to separate one from the other. And we continue to divide the definitions into still more specific designations, until we all accept that a castrated ram is a “wether,” and the tastiest bit of a lamb is the “chop,” and so on and so forth.

It wasn’t until a thousand years ago that the Japanese language got a word for the colour green, for instance, and it was still considered just a tone of blue until the advance of Crayolas in the early 20th century. Among many examples, vegetables are still called ao-mono; blue things.

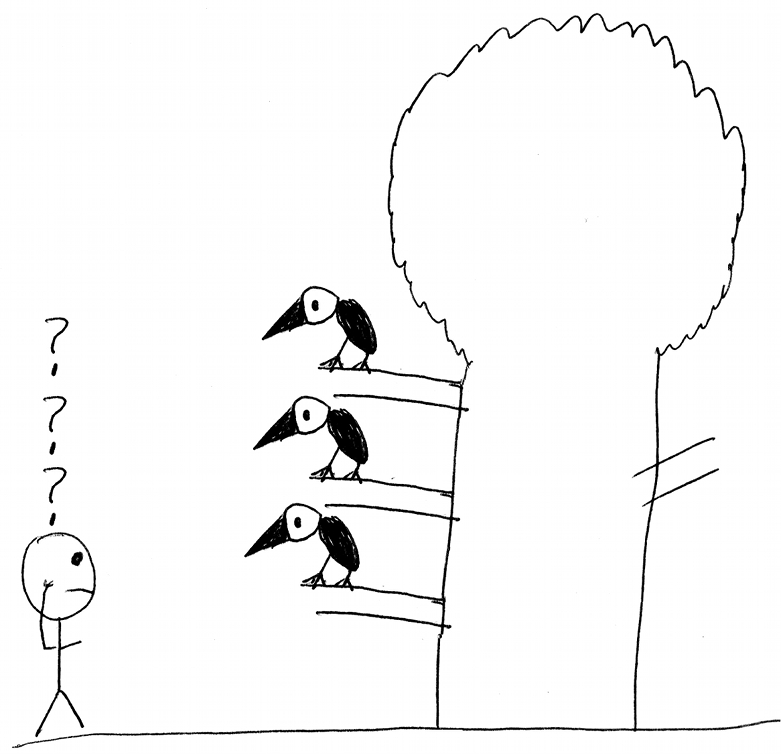

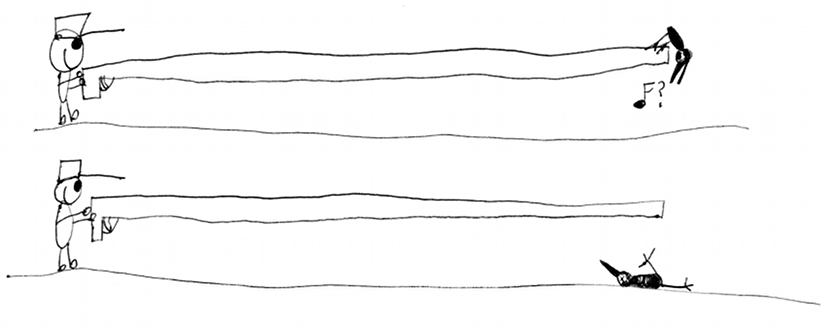

Images, on the other hand, are visual recordings of the world; let’s say I took a photo of a sheep. It might be my favourite sheep, we might even be intimate, but the image doesn’t say that. Now, somebody could look at the photo and project their own fear of sheep on it, not for a moment considering the luster of the pictured sheep’s wool, or the shine in its eyes. This person will just recall the trauma of the great sheep stampede of 2003, and the months spent in hospital after that. Damn sheep…! Sending an image out into the world unchecked can be a risky business, you never know how others will perceive it — and I think of the Muhammad cartoons as much as of any given person’s Facebook photos.

It is said that images are worth a thousand words, but nobody said which words those are. Hardly clear-cut textbook definitions, more likely a chattering, discursive debate with itself, weighing multiple views against each other without really deciding on either, but your sister might like this, and should we maybe go for coffee somewhere? Now, that may resemble how many people actually talk, but also the way many read images, or perceive reality for that matter.

So, images are intuitive, rather than specific; ambiguous rather than concrete; meandering rather than direct. They are a roundabout way of communicating, not like the above, bare-boned definition of language. Comparing the two on language’s terms isn’t really fair, images have entirely different strengths, speaking (as it were) to the viewer’s emotions, experience, and senses. More like music than like boring old text. At the same time, stylised images are used to bridge language gaps, such as in internationally standardised road signs.

And sure, it’s not like language doesn’t have its ambiguities and double meanings, such as in poetry where we try to describe abstract, inner-life concepts in real-life, hands-on terms. There’s a fuzzy zone where we read images and feel language; it exists, but for the sake of argument, let’s not go there in this context. There be dragons, and wolves in sheep’s clothing.

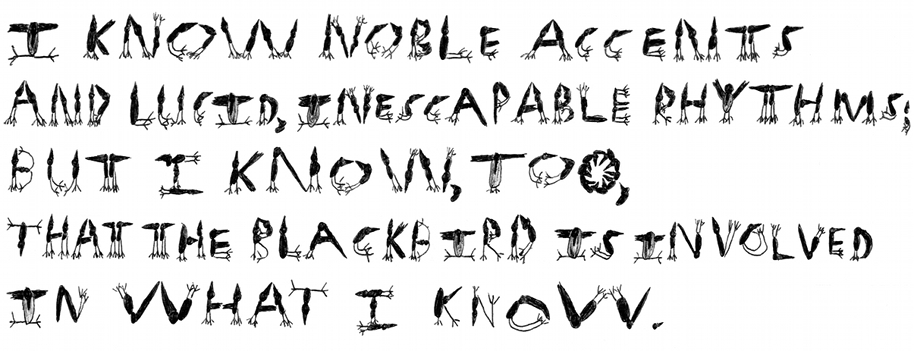

Since we’re doing the broad strokes here, I’d like to address the ways we talk about this thing we call “comics,” then. Comics as a form of communication has grown to be incredibly diverse in expression and intent. We don’t even need to go into the (perceived) mainstream just yet, when much more interesting things are happening in the “alternative” parts (ie, “everywhere else”). Gifted creators working in comic memoir, comic medicine, comic reportage, comic poetry, abstract comics, comic music, and other forms that kinda still need to be named. Mind you, in the previous sentence I’m using the word “comic(s)” due only to the sore lack of a better term.

Now, I’m perfectly fine with everything from newspaper dailies to graphic novels being lumped in one category, along with the Bayeux tapestry, IKEA manuals, altarpiece triptychs, early 20th century woodcut novels, Comic Life montages, cartography, and cave paintings. What I would like is to separate the goats from the sheep, so to speak. Not in a qualitative way, as canons tend to be loaded with bias. So is the word “comics,” however, even if we have gotten used to it not being all about smart, cute kids saying adorable things, or grown men falling in banana peels.

Shall I even go on to what comedians like to call themselves? At the core of it, “comics” is a nonsensical, nondescript term, used as if all film were called “talkies” still — but I’m not going to make a fuss about it like those people who recently complained about anachronistic computer interface icons. Because that was just silly, right? The world changes, and things in the world (such as desktop icons, or comics) change faster than our language can keep up.

What kind of broad statement can you even make about “comics”? That they’re sequential in nature – except when they’re not? That they are all printed? Please, that had whiskers on it in the last millennium! Certainly not that they’re comical, that is to a large extent reserved for short-form “strips”, like some webcomics and the newspaper strips of old. The body of “comics” has become so complex and huge that we need to find proper names for its organs and limbs. Take the “graphic novel”. No, please, take it. That poor, abused, disowned appendix of a term.

The graphic novel has been scolded for being a public relation stunt, invented to allow decent, grown-up people to read “comics”, and I couldn’t agree more. There was a time when nobody would be caught dead reading a comic, more or less because the form had been so deeply entangled with its name and the connotations of childhood silliness that went with it (When was that again, you say? Five minutes ago? Oh, how time flies), so comics was in grave need of a facelift. And it seemed to work, until some publicity smartass decided that the latest Punisher or Green Lantern collection qualified as a graphic novel, too. Then the old, trusty-as-they-are-filthy, mechanisms came into play and muddled the waters once again.

We can quibble about semantics for a paragraph if you like: “Yeah, but Watchmen was serialised at first, so it’s not a graphic novel!” So was Dickens’ works. Watchmen was always intended as a finite suite of chapters, not an ongoing smack-down soap opera. Almost like a novel or something. “Even Eddie Campbell disagrees with the graphic novel tag!” Yes, well, if I read his manifesto right, he really just doesn’t accept that “graphic novel” might become a qualitaty mark to raise the price tag, or indicate that graphic novels are “better comics”. They’re not, they’re just different than some other kinds of comics. It’s a matter of intent, rather than shape or binding.

End of quibble. You can see similar discussions happening over manga, or the budding scene of bandes desinees in the English language market. Geographical or cultural nomenclatures that somehow are miscontrued as genres, when they are actually as wide as, or are in fact expanding the art form we currently call, comics. We’re already burdened with the rather idiotic “OEL manga” “genre” which are just western comics influenced by Japanese comics. The fact that Western creators take inspiration from manga is perfectly legitimate, it was about time really. Again, it is the consolidation of either as a genre that raise a hackle or two — and the implication toward and among readers that there is a difference; “I don’t read comics, I only read manga.”

A few examples from day-to-day media consumption: Reading a positivist blog post about a female reader who didn’t think she would be into “comics,” but elaborates how captivated she became by Wonder Woman; any which kind of media going on at length about the success of “comic book movies,” meaning the multi-feature setup for Avengers Assemble, and Nolan’s Batman flicks; academic papers promising to delve into propaganda in comics, yet touching only upon Superman or Captain America kicking Hitler’s ass, or maybe, if the scholar is up to date, that horrible redneck vision that is Holy Terror.

The (US) mainstream, or what is considered as such, is centered around fan worship to the extent that “comics” seem to have become synonymous with “superheroes” and, by implication, anything not superheroes is deemed off-mainstream. But superheroes. Aren’t. Comics. They’re not even a genre, but tucked somewhere within the pulp genre, which, in its heyday, spread from dime novels to radio and cinema periodicals. Pulp settled into pop culture, and devolved into IPs, meaning in this case industrial properties; there is nothing intellectual going on in that department.

Yet I’d hazard that Chris Ware, David Mazzucchelli, Art Spiegelman, Craig Thompson, and Charles Burns really fit as neatly in the mainstream bracket as the the contemporary fantasies of superheroes. Of a different kind, or sphere, certainly, but I’m not going to question the financial or editorial savvy of Big Six publishers like Random House. That “comics” become interchangeable with a cultural meme is just further sign that the already bent and spent term has outstayed, outlived, and out-welcomed its welcome.

Looping back awkwardly to my attempts at definitions from the beginning; while our concept (or image) of “comics” may be well-rounded, diverse, and panoramic, the language we use to talk and even think about them is not a razor-edged vocabulary — rather, it has been dulled down to a blunt instrument by slipshod habits and flock mentality. I don’t claim originality, it’s hardly the first time the subject is brought up, and I don’t offer any solutions. Until somebody has a Eureka experience, and manages to have the new term stick.

Until then we’re stuck with lame old “comics,” but instead of backing away from neologisms like “graphic novel,” we should just embrace them as non-qualitative, metaphoric descriptions that may open up new meanings and interpretations. And qualifying our terminology about different expressions within the form doesn’t do any harm, either. Still, I do think we should get the comedians to call themselves “jokers.” Unless DC has that term trademarked for their Bat-franchise.