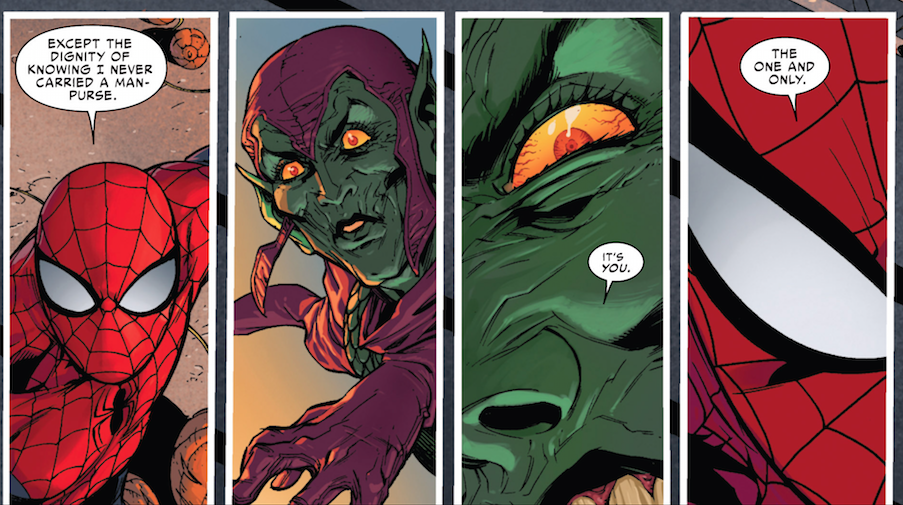

In the above scene by Dan Slott and Giuseppe Camuncoli, the Green Goblin at first thinks he’s fighting Doc Ock in Spidey’s brain (as Osvaldo Oyola explains in his

Which makes sense, to some degree; Peter’s wise-cracking has been one of the characters consistent tropes through the years, more reliable than even his (occasionally black) costume — a point of stability in what Osvaldo correctly points out is decades of ret-conned, indifferently written incoherence

And yet, looking at that sequence, I realized that Spidey’s humore has never exactly made sense to me. Peter Parker is not, as he’s generally written, witty or even particularly cheerful. His backstory is all about trauma; he’s a bullied, bitter, guilt-ridden, whiny nerd, worrying about his Aunt May and filled with insecurity and neurosis. And then all of a sudden, he puts on the costume and he’s nattering on about man purses like he’s got not a care in his webhead.

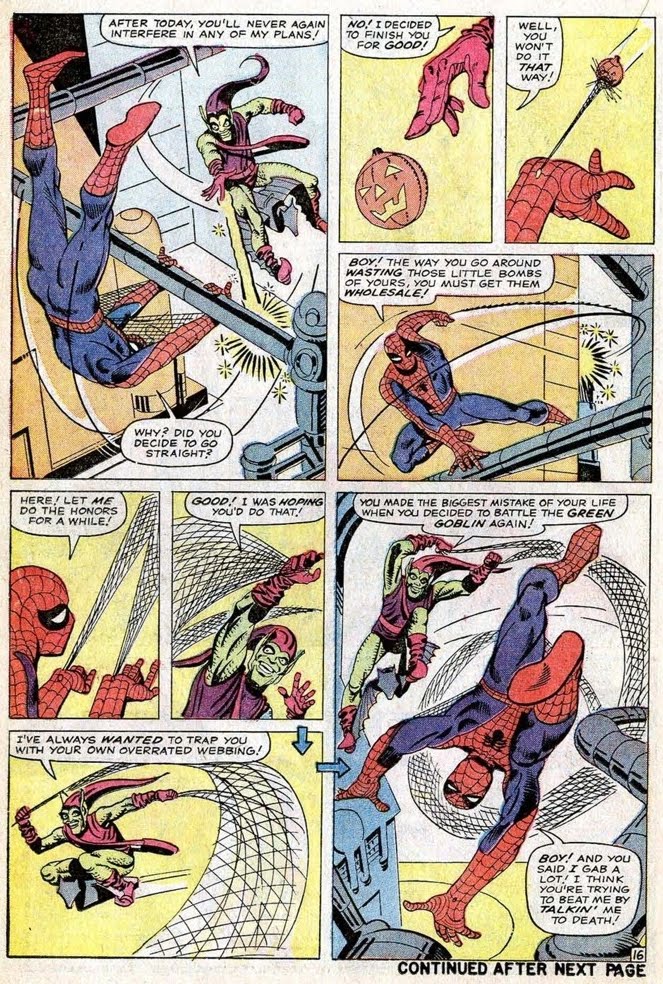

You could explain this psychologically if you wanted to I suppose, and I’m sure someone has — the happy-go-lucky Spidey front hides Parker’s deep pain; the double-identity gives him the opportunity to explore aspects of his personality that nerdy Peter has to repress. You could also, and somewhat more convincingly I think, explain it as a by-product of Marvel’s creative process; Steve Ditko laid out this bitter, depressing story, and then Stan Lee came in afterwords and filled in the text bubbles with obliviously cheerful blather.

Either way, though, the point is that the multiple-personality disorder that Osvaldo diagnoses in the character is not, or not just, a function of decades of continuity burps and generations of hacks writing on deadline, only occasionally paying attention to what the hack before, or the hack after, happened to do. It’s also something in the character from the beginning. Spider-Man was never coherent; he always had a double identity.

Double identities are a standard superhero trope, obviously. Nor is it unheard of for the superself and the nonsuperself to have different personalities. The Hulk is the most famous example, but the truth is that Superman and Clark Kent, early on, seemed less like one guy in two outfits, and more like two different people — one helpless, nerdy masochistic nebbish; one sadistic wise-cracking swashbuckling asshole. Superheroes from early on, and even iconically, are not one person; they don’t have a single identity. They’re more than one; their selves are multiple.

As folks pointed out in the comments to Osvaldo’s post, this has some interesting moral implications. Kantian morality, in particular, is based in a particular notion of identity and the divided self. For Kant, the true self is the moral self, or the moral law that speaks within you. Immorality is the accretion of transient desire, or really transient personality, that ties you to the phenomenal world, and distracts your brain, or more your conscience, from noumenal contemplation. From this perspective,you could see the split personality superhero as a kind of Kantian parable. Peter Parker is the phenomenal self, riven by neurotic doubts and distractions; Spider-Man is the noumenal self, devoted to the single-minded pursuit of duty.

That doesn’t actually sound much like the Peter/Spidey we know, though. Spidey is hardly a serene slave to duty; on the contrary, as Osvaldo explains, Spidey is all over the place, sometimes a self-sacrificing martyr, sometimes a cheerful babbler, sometimes a brutish thug. He’s hardly a consistent example of WWKD.

Maybe that’s the point, though. Chris Gavaler has argued that the figure of the Clansman was an important pulp precursor and inspiration for the superhero trope of double identity. The KKK, of course, used the double identity as a way to wreak evil — being somebody other than who they were allowed them to sidestep duty and the moral law, and embrace the exhilarating phenomenal pleasures of violence and evil. Kant presents good as arising from an eternal, unwavering identity. It makes sense, then, from his perspective, that to abandon morality you would first abandon a stable self.

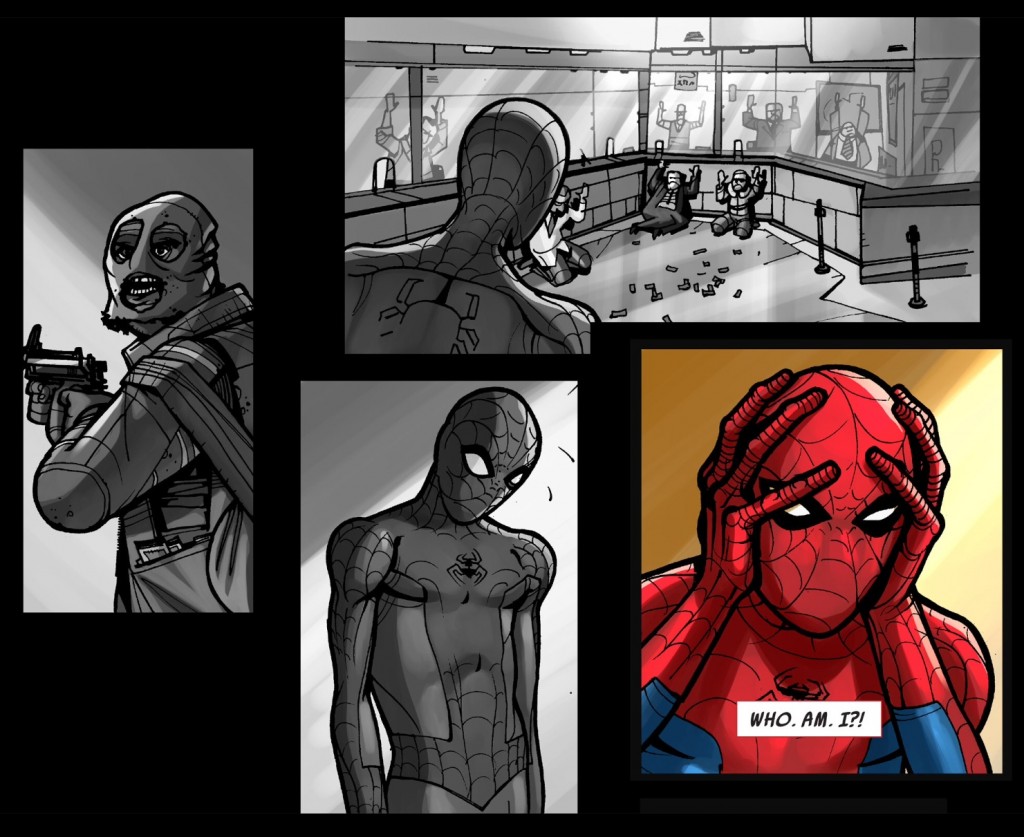

And that, again, is what superheroes do. Peter Parker puts on a mask to go hit people really hard without legal authority or due process of law. That’s not duty; it’s vigilantism. And that vigilatism is enabled by forswearing one identity; Peter Parker wears a mask so that he doesn’t have to be Peter Parker, with all the attendant moral and social obligations, just as the KKK put on the hoods to escape their dull selves bound by law and duty not to shoot and lynch their fellow citizens. As Doc Ock’s possession of Spider-Man suggests, superheroes escape their identities in order to become supervillains. The more continuity renders their selves incoherent, the more true to themselves they are — that self being, at its coreless core, bifurcated, morally adrift, and un-Kantian.

From Spider-Man, “Who Am I?” by Joshua Hale Fialkov and Juan Bobillo and JL Mast