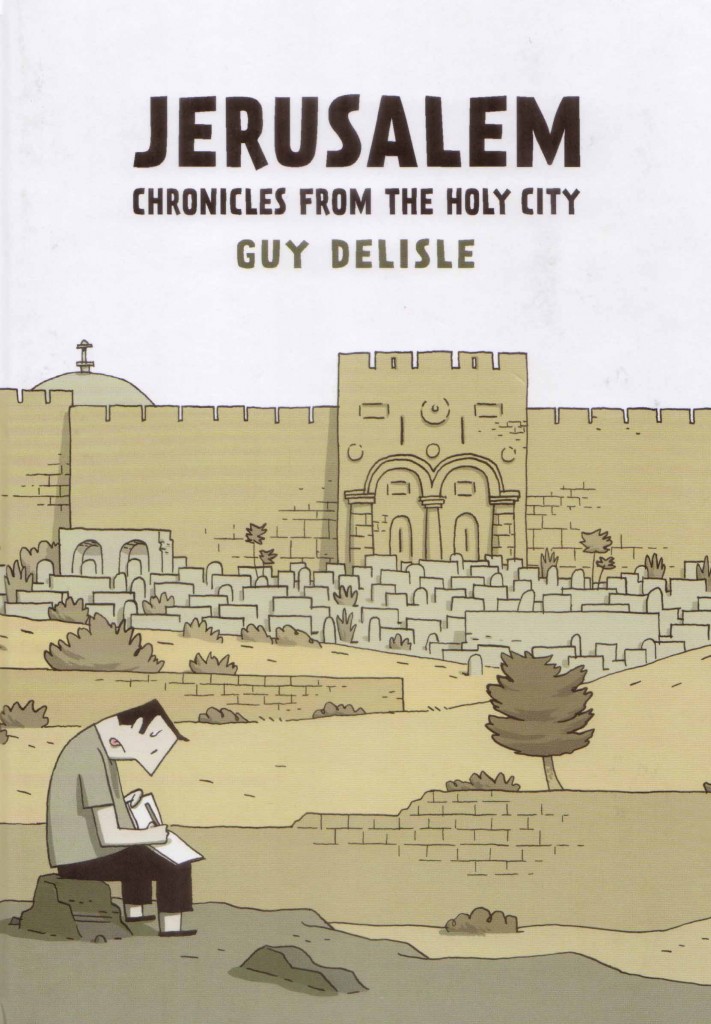

The cover to Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem shows him sitting at the edge of a Muslim cemetery on the Mount of Olives facing the Golden Gate, the gate through which the Messiah is expected to enter the Holy City. One could see this image as a conjunction of faiths and a metaphor for all that Delisle encounters: the Palestinians (Muslims and Christians) in their graves; the door closed to any true understanding of the situation; the cartoonist sketching furiously in the foreground; all of them awaiting salvation.

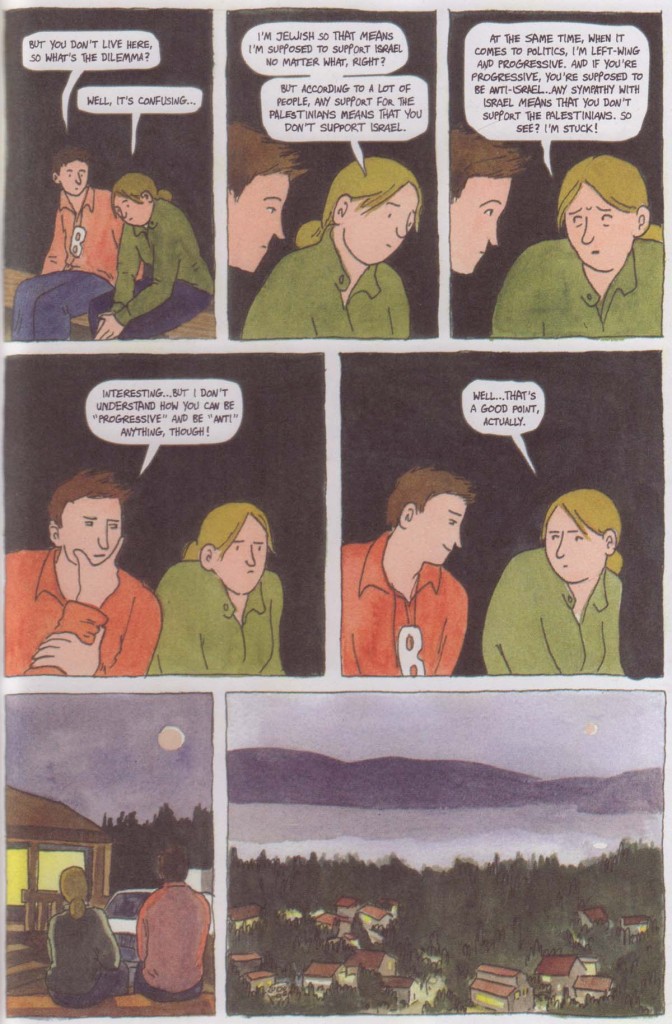

Delisle presents himself as a blank slate, as devoid of any information as the doodle with which he represents himself; a surprise considering his comic travelogues through Shenzhen, Burma, and Pyongyang. At one point he even seems perplexed that while Israel and many of its citizens view Jerusalem as the capital, most countries only accord Tel Aviv that honor and situate their embassies accordingly. It’s almost as if television, the internet, and the Arab-Israeli wars had never occurred. In many ways, he’s like the guy sitting next to you on your bus tour of Israel, the one who knows next to nothing about the place he is visiting. Unlike most tourists, he has months to rectify his ignorance. How one feels about this is a matter of perspective and depends on what we expect from a reading experience.

The intention one suspects is to allow both Delisle and his readers to set off on a journey of discovery together—no back tracking, no overarching narrative omniscience, no real meaning—the gentle meandering rhythms of expatriate life distilled to several semi-significant and ordinary moments in time. The idea here being that what best signifies any city (even Jerusalem) is not its monuments, its festivals, or its tragedies (though these are give some space) but its commonness; the quotidian lives of its citizens—the parties, the daycare hang-ups, the shawarma encounter, the transportation stories, and the amusing anecdotes about Arab women. In place of discernment, Delisle offers affirmation and comfort, a year in the life of a cartoonist house husband whose partner is working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). What little information we get is conveyed at a slow pace and is quite disconnected, taking on the fabric of directly recorded experience with little heed to the editorial mindset. It is very much an unvarnished journal comic, certainly not a guided tour or an essay much less an encyclopedic account on specific areas of interest. The author’s prose style, cultivated through years of travel writing, is plainer than his drawings: short, unpoetic, and unexamined.

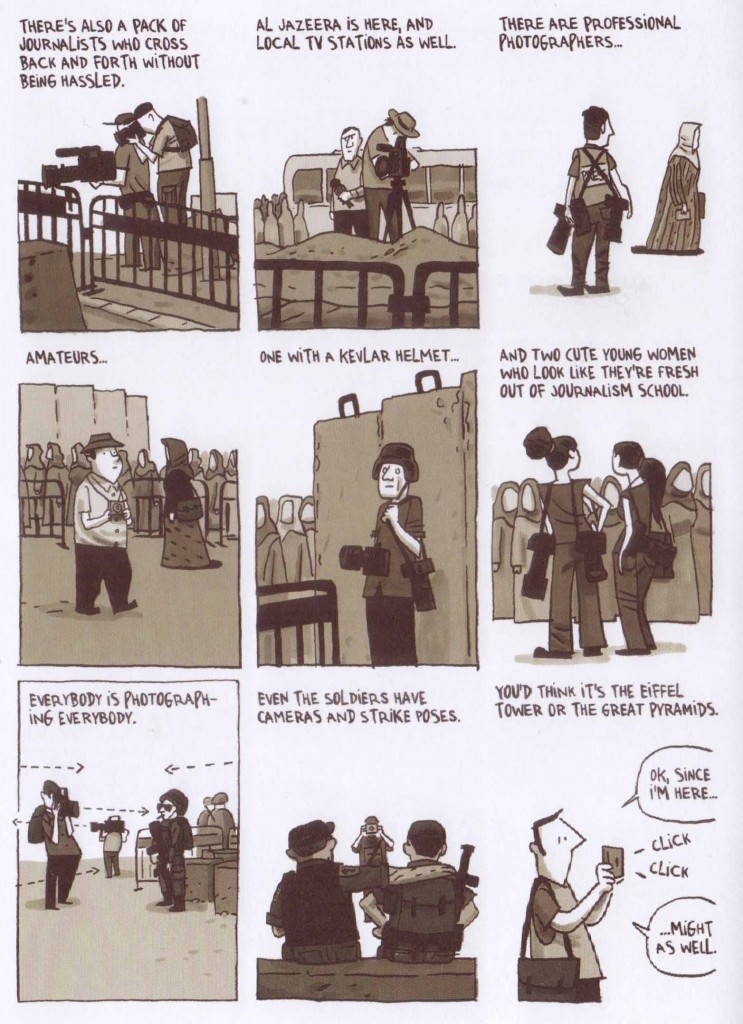

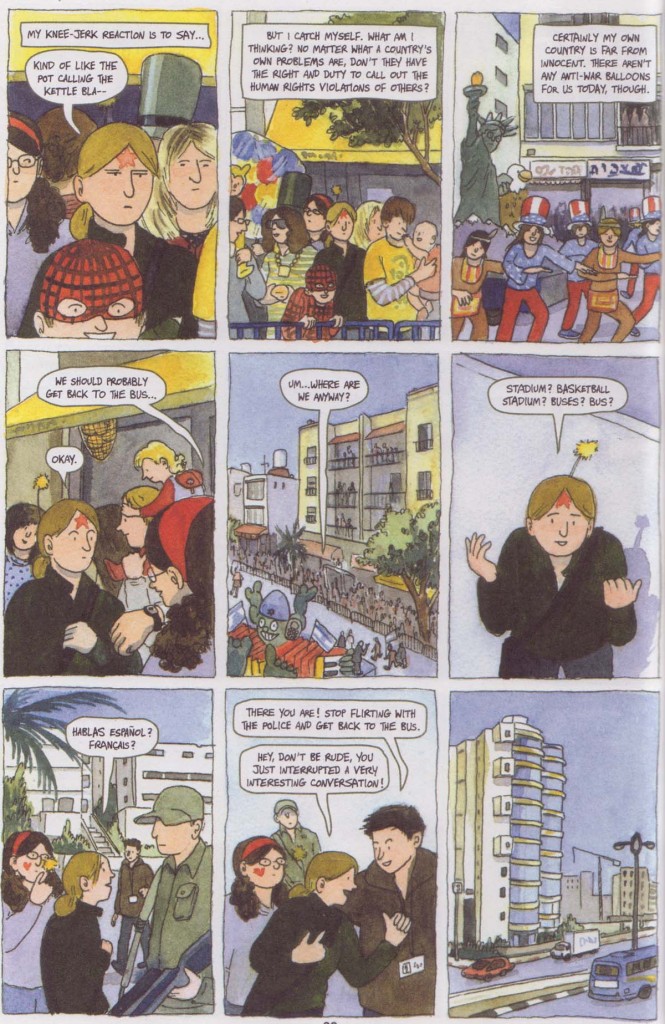

His first substantial political encounter comes 38 pages in (there are a number of minor instances before this) when he visits a border crossing and the West Bank barrier with Machsomwatch, an Israeli women’s peace movement. At the crossing, the crowd is large and slow moving, the Israeli guards fully armed for war and happy to allow their pictures to be taken. Almost inevitably, there is a misunderstanding and then tear gas and stone throwing. In attendance, the television crews and Delisle; both hopping on the same media treadmill (their’s faster, his slower) we’ve seen re-enacted over the years; the artist’s eye paralyzed, the reader’s mind and emotions unengaged—the bulk of these experiences freely available all year around to the tourist looking to cross from an Arab country into Israel. It made me wonder why he didn’t visit the duty free shop while he was there (I guess there wasn’t one at the crossing).

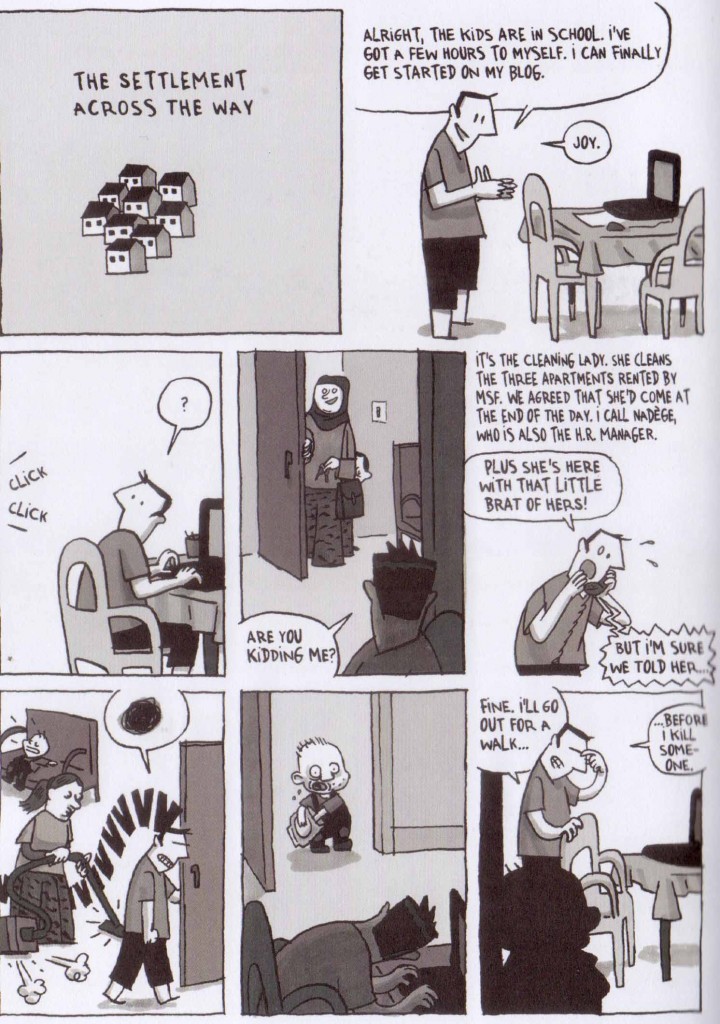

To be sure, Delisle is not opposed to painting himself in a bad light. His reaction to the arrival of his cleaning lady is irritation as she tips his blog creating activities into disarray. He throws a small tantrum and makes a frustrated phone call to his wife.

The comic under review is of course that “blog” or rather the result of that year of engagement; conveying all the daily grind of perpetual enforced communication in a tone strangely shy yet smug.

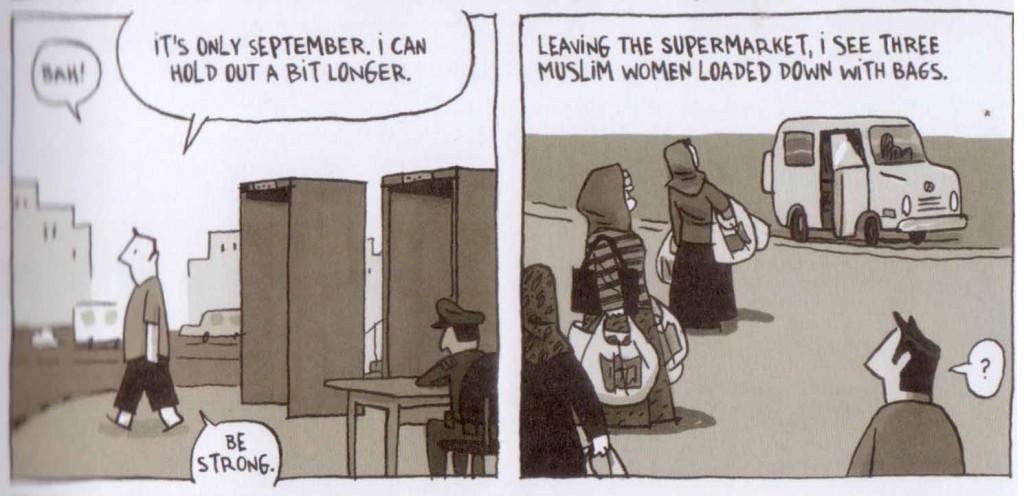

Jerusalem works best when Delisle’s art meshes with his subject matter in the kind of light social observation you find in his earlier comic, Aline et les autres. The denouement of his hunt for the perfect bowl of cereal ends to sort of interesting effect when he sees bag-laden “Muslim women” leaving the settlement supermarket he has chosen to boycott.

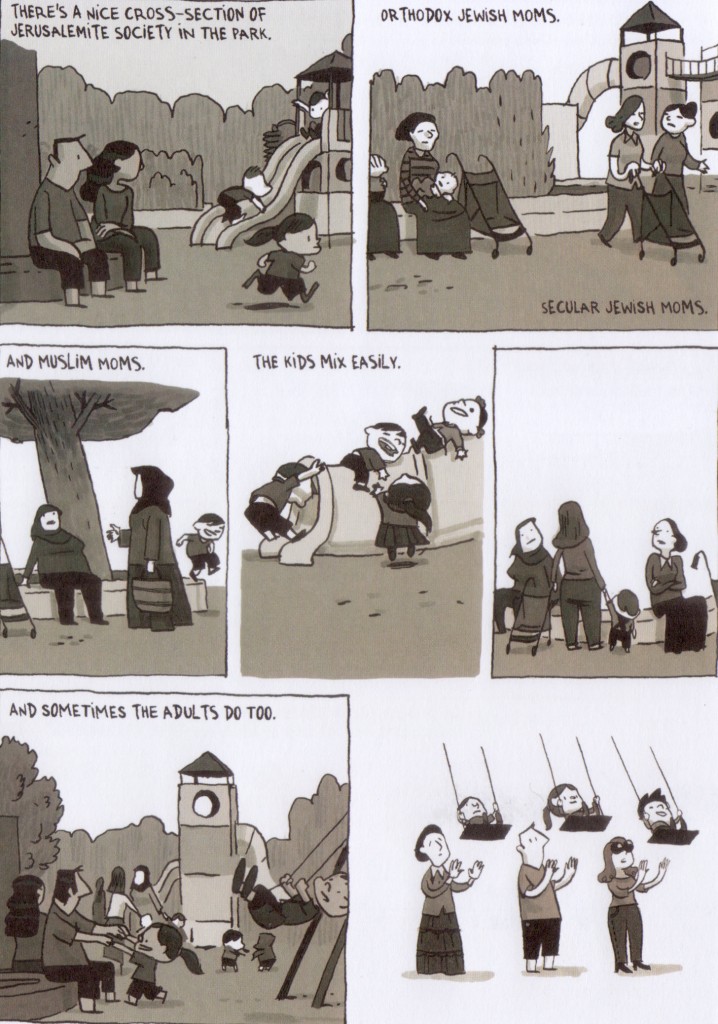

There’s a little homily in a playground about mothers, children, and racial harmony (I grant that the reader’s cynicism will need to be checked in at the point of purchase).

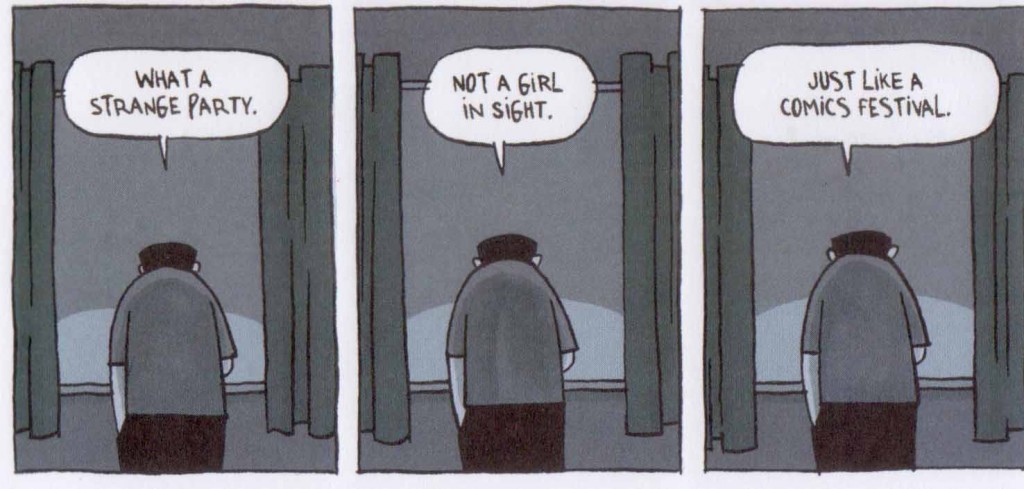

There’s the part where he compares an “all-male” Arab wedding to a comics festival…

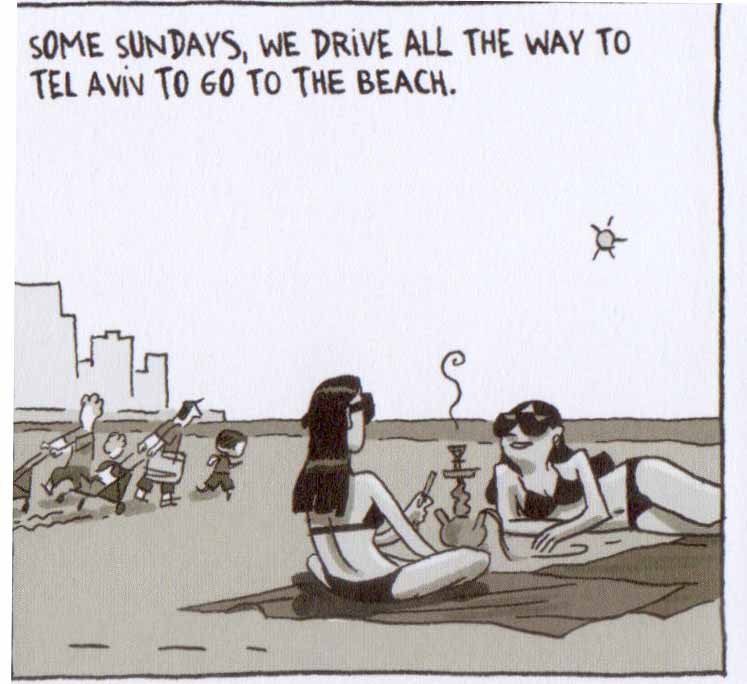

…and also some girls in bikinis with a hookah.

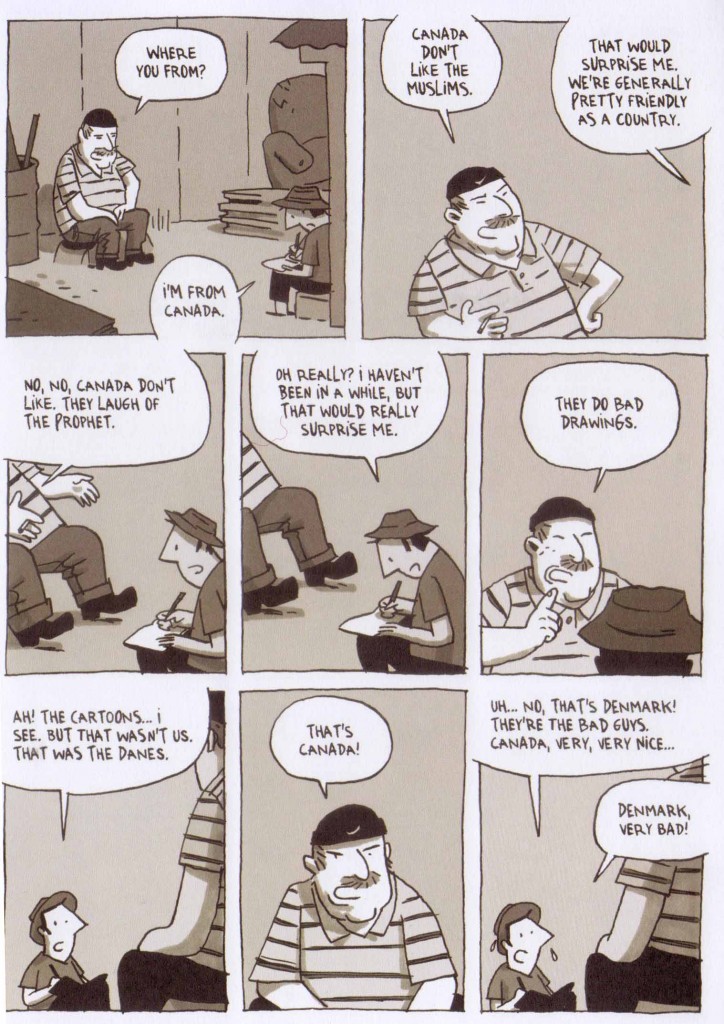

His embarrassment and exaggerated spinelessness can also be charming at times.

Most of it, however, reminds me of a photo album with commentary, the kind of ritual myth making experienced when a friend returns from his travels. A tale of gold-lined domes made on the backs of mercury poisoned death row prisoners is tucked in, as is his displeasure with a Zionistic Israeli tour guide (recognizable at least). And as with all such tales, there will be the travel disasters to punctuate the proceedings. In the case of Delisle, the multitude of El Al-related airport hassles and a lengthy sequence concerning the loss of some car keys down a lift shaft. Always amusing when the canapes are being served. The only problem being that Delisle isn’t your friend, and you’re not terribly interested in his family life and travel pics. Unless of course you are, in which case Jerusalem and his many other comics might be just what you’re looking for.

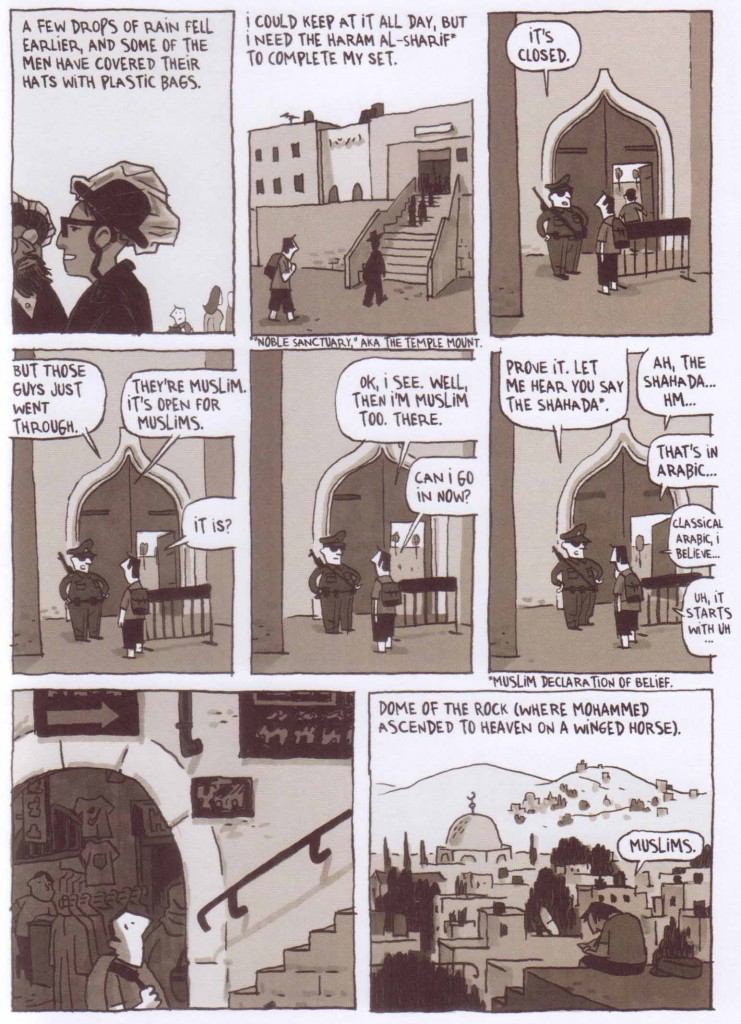

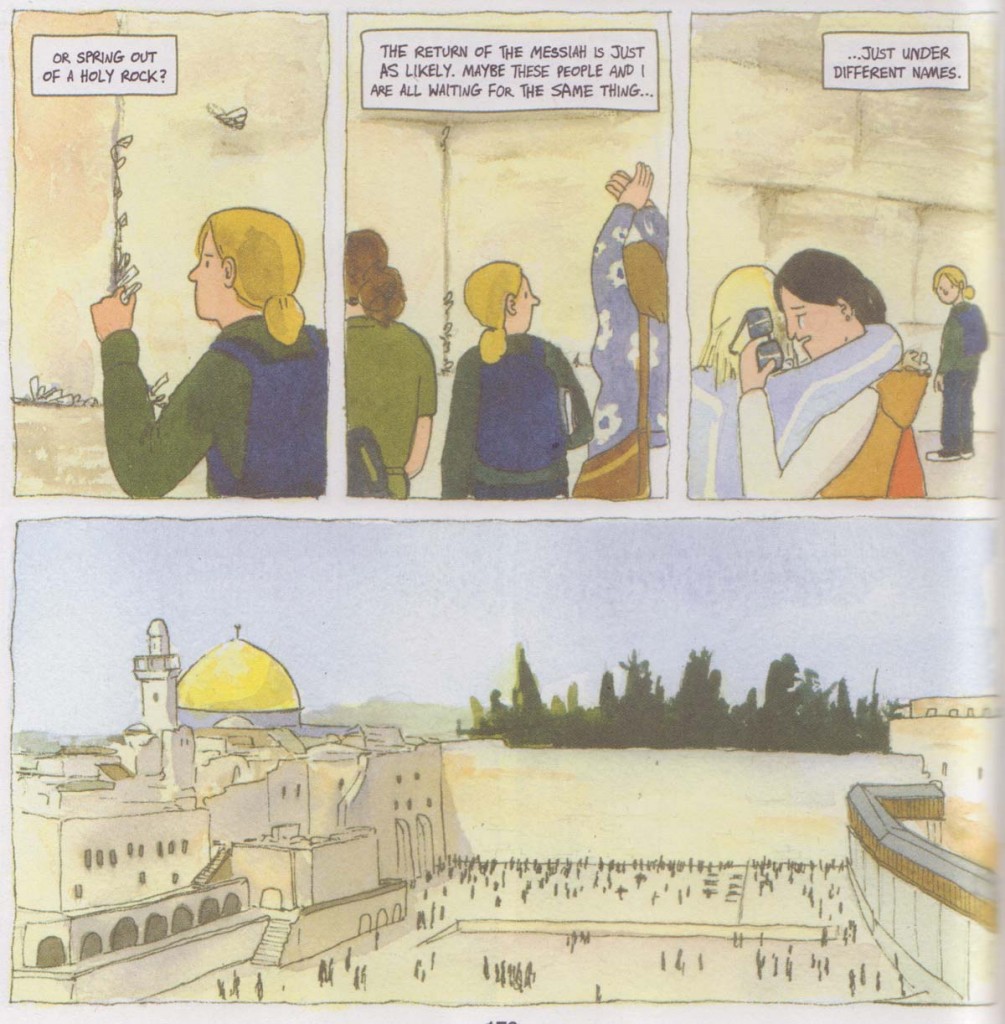

Even so, the reader is advised in advance that this is not a book to be read all at once, the banality of the insights here engendering feelings similar to those encountered when reading a large collection of cartoon dailies in one sitting. The off-days on the strip accumulate, its charms disappear, the limitations in drawing style are accentuated, the anonymity of the locales depicted become obvious, the jokes fall flat, life in all its disjointedness and directionless comes to the fore. Delisle has a dogged commitment to this aesthetic even taking time to relate how he fails to complete a visit to the three holy places of Jerusalem (the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Western Wall and the Temple Mount).

His ploy to get through by pretending to be a Muslim is not entirely without credit but there it stops. He neither speaks to these people at length nor inquires into the situation. The lack of curiosity is patent, the superficiality immense. There are short returns later in the comic but to little effect. The Holy Sepulchre is precisely what every oblivious tourist sees—the famous balcony ladder, the Orthodox-Catholic division of space in the church, the photo mad crowds (though strangely none of the religious fervor)—as short and indescript as a one line summary and just as educational.

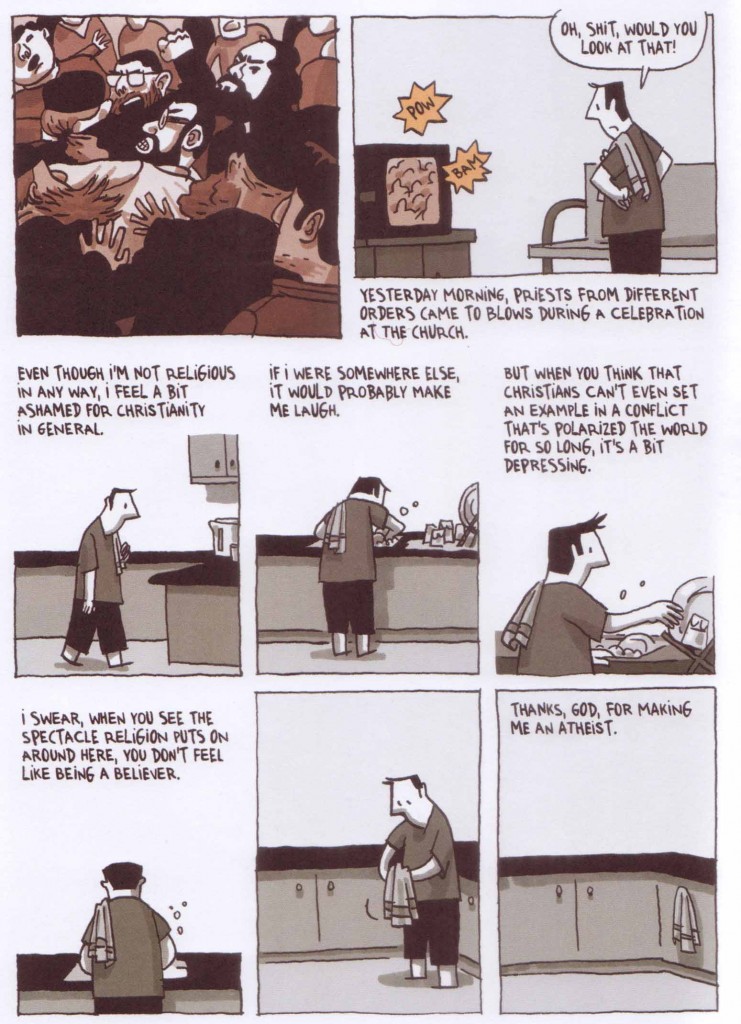

Not surprisingly, the religious naiveté on display beggars belief. Ten months into his trip and Delisle still has to be told what a Messianic Jew is (perhaps its an act of pretense to encourage conversation). And did it really take him that long to find out that merchants rent out crosses for pilgrims wishing to traverse the Via Dolorosa (there are sometimes stacks of them near the Holy Sepulchre)? Earlier in his comic, a sectarian fight in the church seen on television is a moment for hand wringing and a lame joke, not dissection or historical analysis:

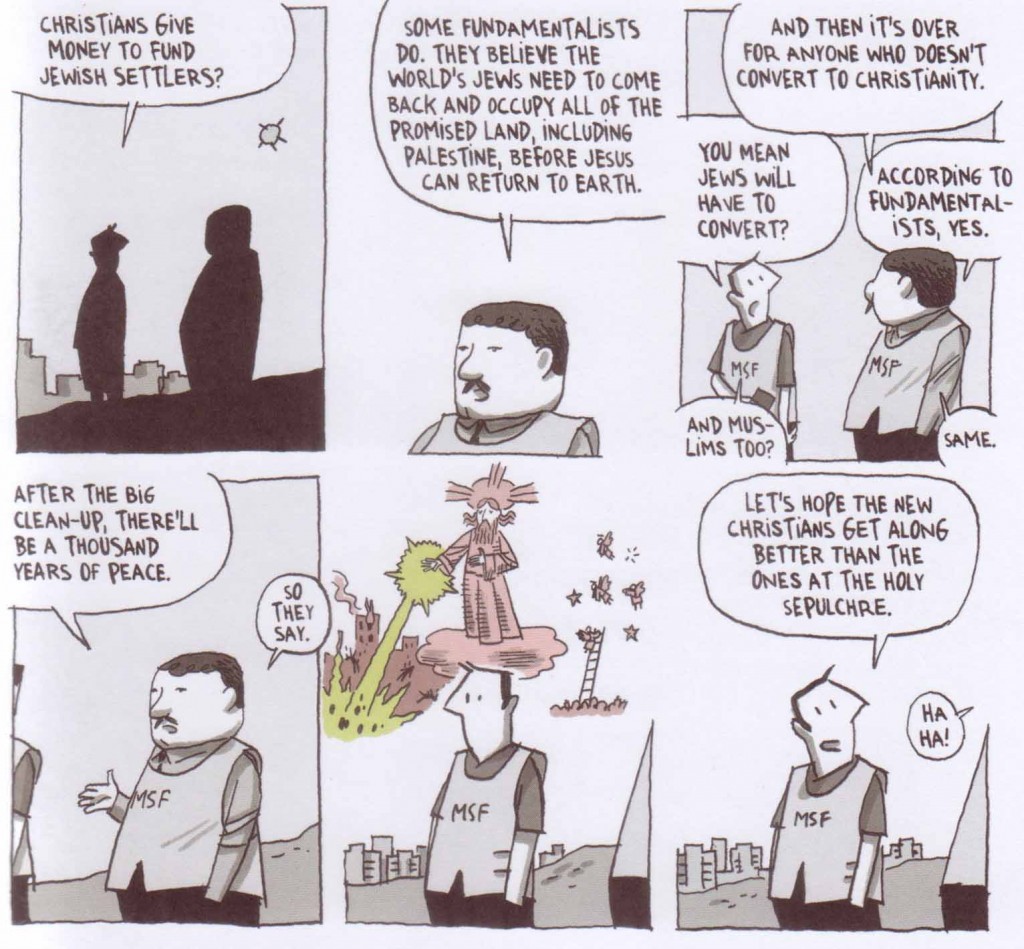

Perhaps Delisle isn’t talking about the same religion which sanctioned the sack of Jerusalem during the first Crusade. Could it be some other sect that has been living under the Status Quo for over a century and which continues to see brawls and property disputes on a yearly basis? Apart from this, there’s a frankly emaciated discussion with a member of the Franciscan order and a couple of prods at dispensational fundamentalists clearly meant as comic relief. Good for a polite guffaw provided one hasn’t heard the same joke done even once before.

There are occasional reprieves from this rampant shallowness. The author’s recurrent trips to Hebron are of some interest, in particular his guided tour with Breaking the Silence.

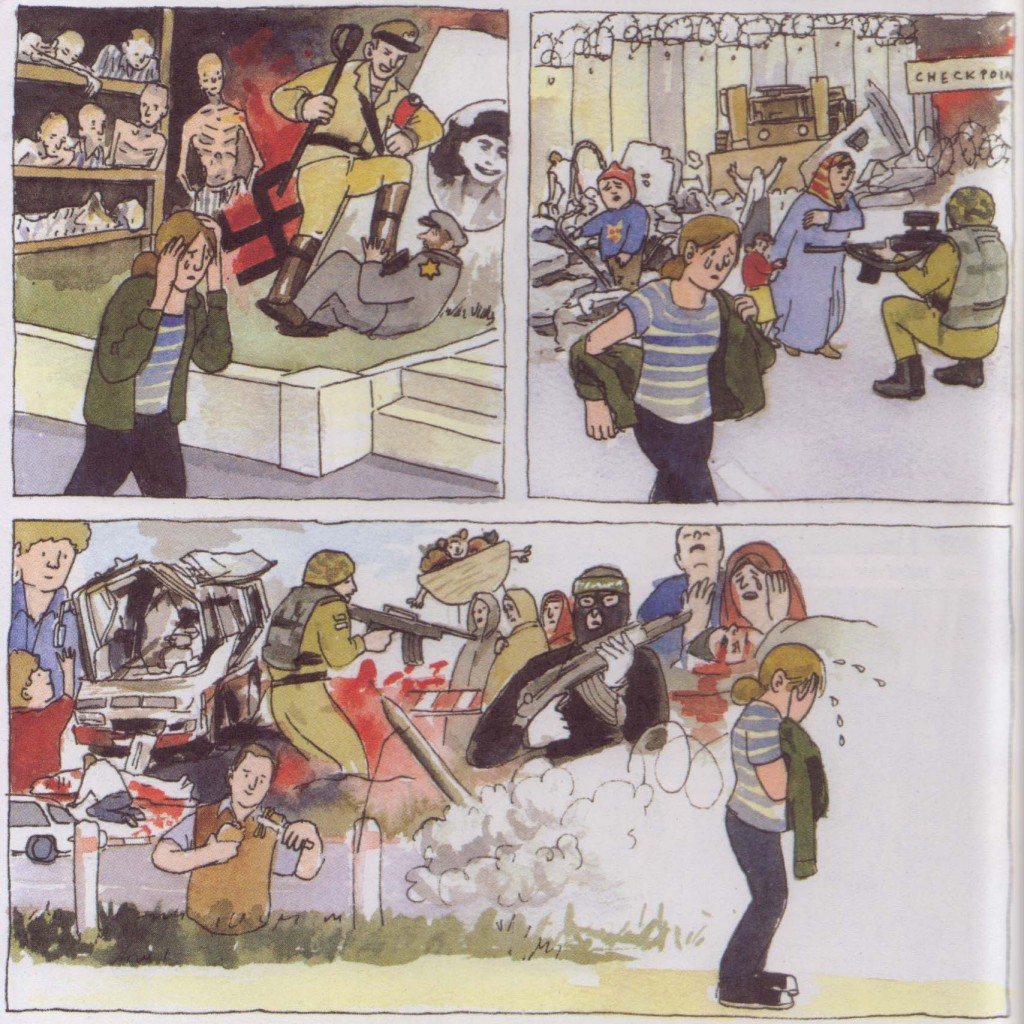

Delisle can be heavy-handed in his juxtapositions but, to his credit, never descends to the level of crass exploitation. The observations in Mea Shearim are also reasonably sharp considering the episode lasts only 4 pages. Most of these vignettes occur towards the tail end of the book and there’s little doubt that Delisle’s narrative improves as soon as he runs out of the usual things to say.

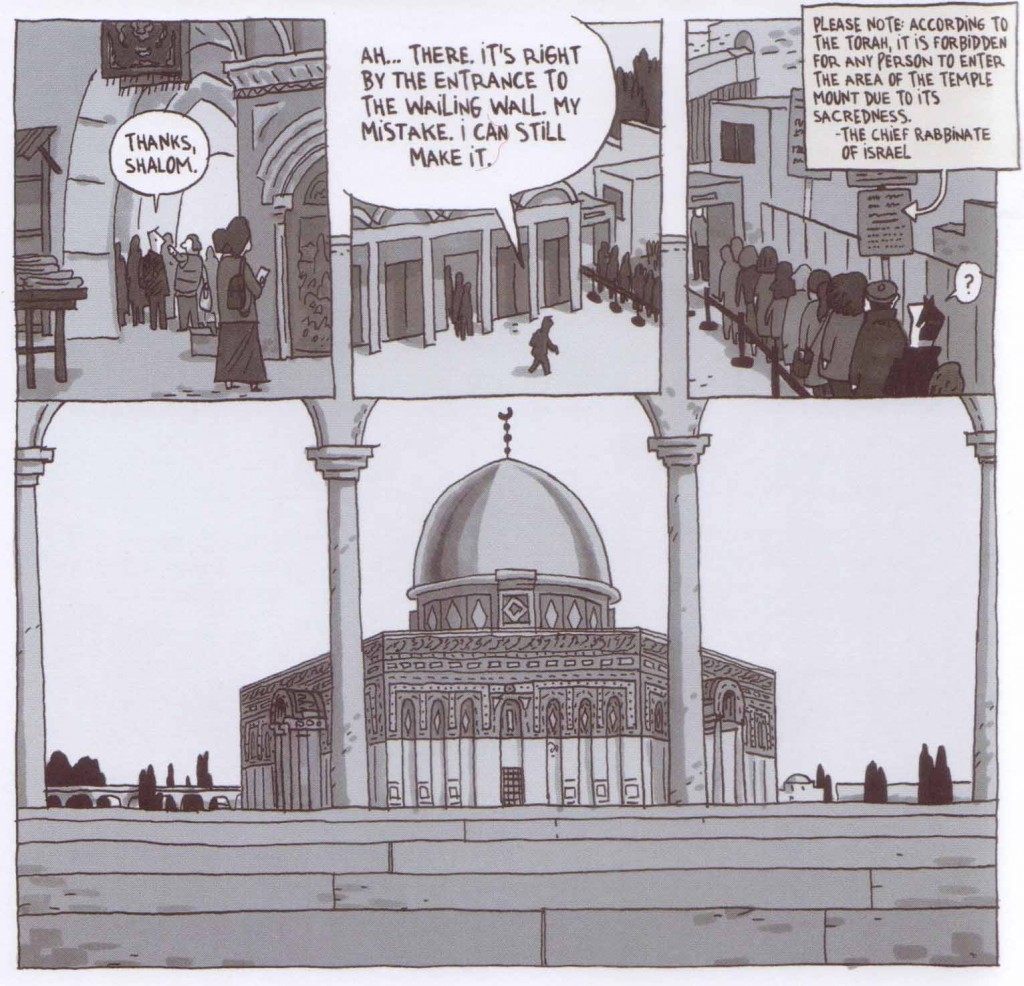

The rest of the long aimless middle section is almost too painful to relate. The return to the Temple Mount with a picture of the Dome of the Rock is of less interest than the most token tourist photo (the Al Aqsa mosque gets slightly better mileage).

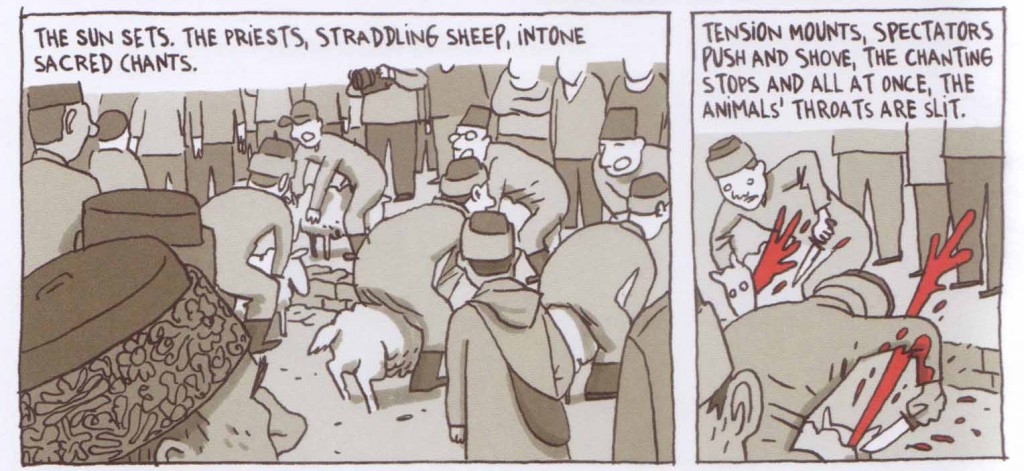

Delisle’s depiction of a Samaritan Easter (Passover) celebration on Mount Gerizim only makes us yearn for a proper photojournalistic account. The picture post card trail to Bethlehem, Massada, the Dead Sea, and Jordan is little better.

Delisle’s shtick is to tease out truth from the commonplace. He never does what you would never do in the same situation, hardly thinks an improper thought and almost never tells you anything which you don’t know yourself. Jerusalem is the playground viewed absentmindedly for a moment through your house window, as innocuous as people dying on a television screen—never close, never real, no scars, no blood, and never painful. Seldom does Delisle push pass this point. An instance of this occurs at the moment of departure when his housekeeper tells him that her house is about to be demolished. The episode is only two pages long but for once, it’s personal.

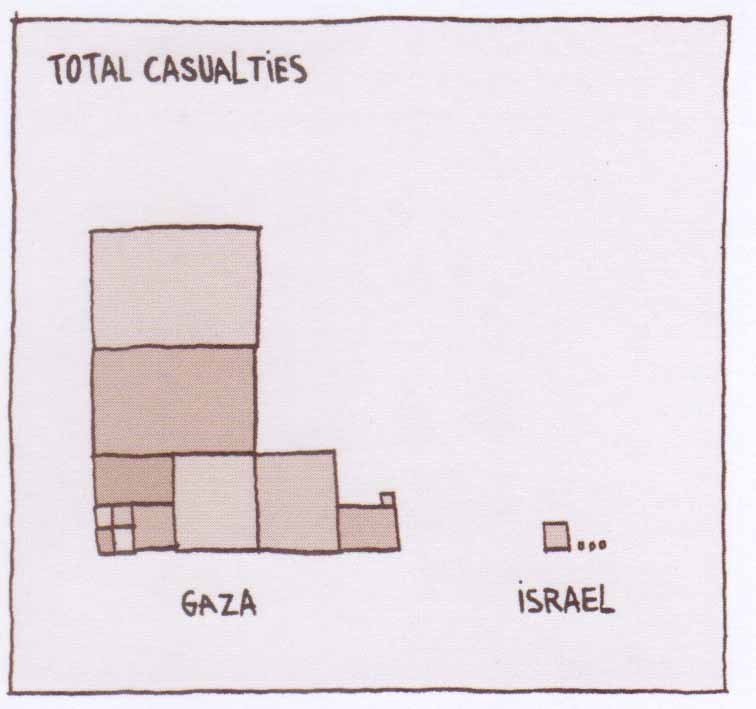

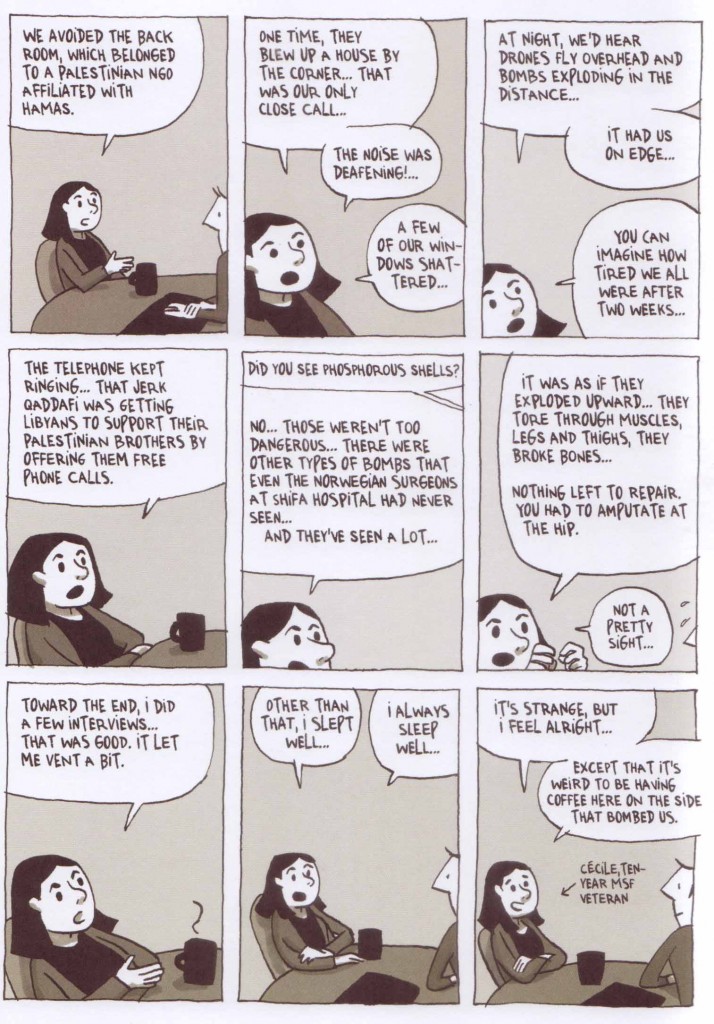

The graph which Delisle’s produces mid way through his depiction of a Gaza bombing campaign (a central event in his journal comic) is eerily representative of much his delivery. The prose apeing the art in a consistent blank drone with neither the vocabulary nor technique to elevate the text. His pedestrian interview with Cecile is as close to fine journalism as he gets, the 10 year veteran of MSF dissolving into an insignificant collection of lines and shade spouting words from the left border of each panel. Some will see this sequence as an attempt to let the words speak for themselves. In which case, I must ask, why comics?

The narrative’s positioning in the arena of the trivial and everyday is no excuse for poor art. Consider the following amateur photography project by Still Yang. A simple set-up with a long zoom facing a bus stop situated in a Jewish orthodox community; the shots taken at the discretion of the photographer. The truth is that I found more humanity and insight in this simple project than much of Delisle’s comic. At the other end of the spectrum, there’s something like Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Jerusalem: The Biography—written in an entertaining style but with immense erudition and an all encompassing but popular intent. It begins with mythical history and ends on any morning at 4am in Jerusalem: the rabbi of the Western Wall at his prayers; Nusseibeh, the Custodian of the Holy Sepulchre knocking on those “ancient doors”; the Ansari Custodians of the Haram supervising the opening of the gates of the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa.

Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem has neither the concentration nor sweep of the art and ephemera which have preceded it. The cracks in the artist’s craft were hidden in his adaptation of Pyongyang, the rigidity, the stunted acumen, the plodding pace, the bland discursions all feeding and reinforcing received conceptions of an authoritarian North Korea. These flaws are laid bare in Jerusalem which is morally earnest but sadly leaden and inconsequential.

Further Reading

Noah Berlatsky on the vaunting tedium of Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem

David Leach’s review is my token “positive” inclusion if only because he goes into detail about what he likes. He praises Delisle’s use of the anecdotal story form and singles out the chapter on Ramallah for praise.

S. I. Rosenbaum on Delisle’s political and social obliviousness.