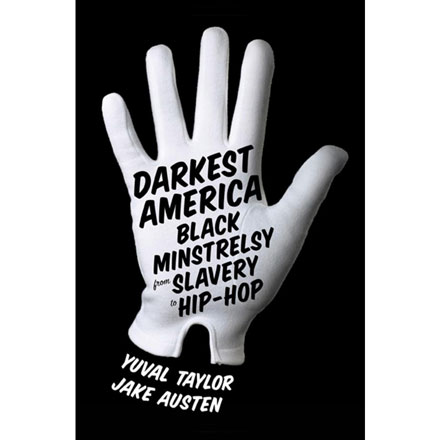

Let me say up front that I really liked Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop by Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen. It does one very important things you don’t often find in books about American minstrelsy (I’m looking at you, Love & Theft)—it describes what a minstrel show was like in clear and engaging language that conveys some of the charm of the art form without making you feel like you’re drowning in boring overly-academic prose. For that alone, it’s worth reading.

There’s also this really, really nice moment where Taylor and Austen describe Flournoy Miller and Johnny Lee, both black comedians, doing a blackface comedy routine in the movie Stormy Weather. Then they give a whole paragraph to the history of the routine, which Miller had been doing since at least the Twenties. And then the paragraph ends in this: “By the estimation of black comedy historian Mel Watkins, it was as familiar to black audiences as Abbot and Costello’s ‘Who’s on First?’ was to white audiences.” (p. 292) This bit of contextualizing is so amazing—you get the bit (or a bit of the bit), the bit’s history, and then a sense of the bit’s reach.

But I don’t think that Taylor and Austen ever quite satisfactorily address why blackface minstrelsy was so popular among black people—both performers and audiences. They brush up against it in the chapter on the Zulu parade in New Orleans, when they say, “Zulu history has been largely whitewashed, scrubbed clean of its origins in caricature, parody, and stereotype. Instead, blacks paint their faces out of respect for a tradition that, like the rest of the black minstrel tradition, has always been focused on entertaining its audience. For the Zulus, as for many black and white minstrels in the nineteenth century and earlier, blackface simply stands for a very good time.” (p. 106-107).

Tradition and pleasure are strong motivating factors and I wish Taylor and Austen had wrestled more with the implications of this insight. We like a lot of things because they’re familiar and because we find their familiarity pleasurable. I kept waiting for them to make this explicit—black people didn’t/don’t enjoy black blackface minstrelsy or its popular culture descendants because (or only because) they recognize some truth of who they are on stage; it’s pleasurable because they recognize the performance.

Or let’s look at it it from a slightly different angle. In 1993, Alan Jackson took “Mercury Blues” to Number 2 on Billboard’s country chart. It’s a cover of K. C. Douglas’s 1949 song, which is sometimes called “Mercury Blues” and sometimes called “Mercury Boogie.” “Mercury Blues” contains a line, which, in Alan Jackson’s version goes, “gal I love, stole her from a friend, he got lucky stole her back again” and in Douglas’s version goes, “girl I love I stole from a friend, the fool got lucky stole her back again.” But the line also lives in other songs. In Robert Johnson’s “Come on in My Kitchen” (1936) it goes, “the woman I love, took from my best friend, some joker got lucky, stole her back again.” Back in ’31, Skip James, in “Devil Got My Woman,” sings “The woman I love took off for my best friend, but he got lucky, stole her back again.” But it goes back further to at least Ida Cox’s “Worried Mama Blues” back in 1923—“I stole my man from my best friend, I stole my man from my best friend. But she got lucky and stole him back again.”

There’s a real power in recognition. When I learned about this repeated verse, I felt as if some great secret history of America had been revealed to me in a lightning flash, as if I had learned a way pop culture connects through time. It pleases me to recognize those same words in all those very different songs and I trust that at least some of you will be delighted to recognize them too. And it’s not because all of us have experience passing a loved one back and forth with our best friend. We take pleasure in recognizing the familiar bits. Of course, this kind of recognition of familiar bits can also be disturbing. When you know Walt Disney took inspiration from The Jazz Singer when he made “Steamboat Willie,” how do you ever look at Mickey Mouse’s white gloves the same way again?

So, when J.J. Walker makes his entrance, or later, Flavor Flav, isn’t there a delight in recognition—not of that type in the community, but of that type in entertainment?

Which brings me to the thing that I think Taylor and Austen fundamentally misunderstand. It’s up there in the Zulu quote, but they also state it explicitly on the third page of the book, “The minstrel tradition, as practice by whites in blackface, was a fundamentally racist undertaking, neutering a race’s identity by limiting it to a demeaning stereotype. But what Chappelle and other contemporary performers draw upon is the more complicated history of black minstrelsy.”All this is true. But, it misses an important and complicating component of white minstrelsy—a lot of white minstrel performers thought they loved black culture (I say “thought they” because any kind of black culture white men could have observed in the 1800s would have been carefully performed by those black men, because of the incredible danger the black men would have been in had it been misinterpreted).

In Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, Eric Lott says that, for these white minstrels, “To wear or even enjoy blackface was literally, for a time, to become black, to inherit the cool, virility, humility, abandon or gaité de coeur that were the prime components of white ideologies of black manhood.” (p. 52) (I don’t want to get sidetracked from my point, but I also feel like it’s important to state explicitly how terrible this belief of white men—that they could know black men through mimicking them—was for black men. It is at the heart of why white men could justify all the terrible things they did to black men. White men believed they knew the secret motivations of black men, because some of the white men, white men believed, had literally been black men briefly through imitation.) And this is the hard thing to accept, but the only thing that makes sense of minstrelsy, both black and white: it is racist and demeaning AND it is about a deep fantasy of how awesome it is to be black. Those things are both true, and, in fact, in a racist society like ours, you rarely have an admission of the latter without the former firmly in play.

Once you get that, the power and attraction of blackface minstrelsy—not just the components of the minstrels show, but the actual wearing of blackface makeup—for black people is obvious. If every single thing in the broader popular culture is either explicitly racist or does not mention black people at all (and is therefore implicitly racist), of course the racist art form premised on white people finding so much value in black culture (even if the value they find is not what black people would have called valuable themselves) is going to be incredibly popular with black people. And is it so hard to imagine the appeal of standing on a stage dressed as the object of desire of people who systemically hate you?

But as easy as it is to see the appeal, it’s also then easy to understand why the most egregiously racist components of black minstrelsy fell out of favor as black people gained control of their own representations in popular culture. After all, it is racist and relies on demeaning stereotypes. Of course, when other, less problematic, representations of black people became available, people preferred them.

Still, for a time, it was incredibly popular, both because the bits were funny, the songs beloved, and the insult of blackface muted by the twisted confession of envy that it represented. Yes, it was racist, but what popular culture wasn’t? Blackface was demeaning, but in the hands of black artists, it was also more than that. Black performers in blackface recognized that the culture portrayed by performers in blackface was black culture (or a fantasy of it)—which meant that culture had value, was something worth looking at, even to the very white people who, when they weren’t sitting in the audience, were denying that black people had any worth.

It’s little wonder, then, that its remnants linger on. Blackface minstrelsy was the popular culture for most people for at least half our country’s existence —where our comedy came from, where we heard and learned our favorite songs, and where a type of fundamental “American” sound in music was codified (including banjos and later the Blues)—and there’s still a lot of cultural resonance. And it’s little wonder that those remnants continue to be a source of controversy and pain—because it was racist and demeaning. That’s the legacy of blackface minstrelsy—a source of great pleasure that still resonates in our time AND a source of great pain, which we are still grappling with.