This review first appeared at tcj.com. (Apologies for the lousy scans; I did the best I could, but it was pretty bad in this instance.)

________________

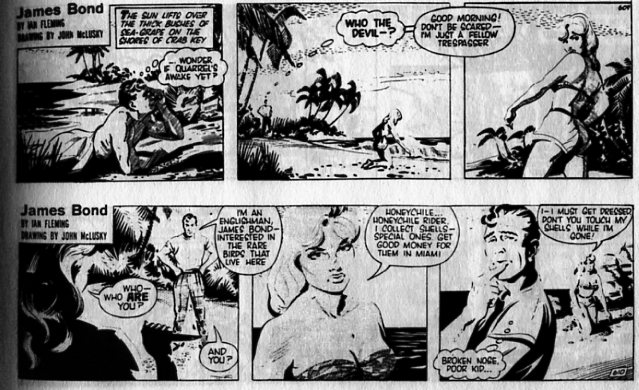

Adventure strip cartooning is basically dead, which makes sense, since I could never figure out how it managed to get up and walking around in the first place. This collection of James Bond newspaper serials from the late-50s and early-60s perfectly captures everything wrong with the form. Instead of a full-throttle adventure romp, you get a plot that stutters compulsively as it desperately tries to bring you up to speed week after week. Instead of pulse-pounding action-sequences, you’ve got images so small you can barely get a motion line in when you throw a punch. And instead of racy, PG-13 innuendo, you’ve got family-friendly not-too-skimpy bikinis — again, drawn at a size that means you need to squint to make an eyeful of the tame fare on offer.

None of which is to denigrate this collection, exactly. John McClusky is a very talented artist, especially adept with detailed linework and shading effects. He rarely gives you a sense of actual action or excitement (which, again, would be awfully hard to do in this format, anyway), but his best work can capture a freeze-frame constructivist drama. Either of these two panels, for example, could be great movie posters:

McClusky is also a fine draftsman, who seems to work very effectively from photoreference. He expertly captures cars, clothes, planes — the world of surface stuff you expect to have presented to you when you’re reading a shallow fantasy of the good life like James Bond.

And, of course, McClusky’s cheesecake, reduced and PG though it is, is thoroughly professional, though a bit lacking in personality. Most of the women in the stories are blandly good-looking, and they start to blur into one another after a while. The one exception is Honeychile from Dr. No. She’s supposed to be a simple nature child, and the slight bit of added characterization seems to frees McClusky to throw in a bit of voluptuous oomph.

All of which basically led me to wish that McClusky had done work which might showcase his talents at a larger size and in a less hamstrung narrative form. But those are the breaks, I guess.

As for those narratives themselves — they are what they are. Produced before the first Sean Connery movies, the touches of humor, technical wizardry, or simply competent plotting those films offered are largely absent here. Instead, Bond escapes death not through cleverness or gadgetry, but mostly through sheer luck; bombs just keep not quite killing him for some reason. He often comes across, no doubt inadvertently, as dumb and bumbling— more like a real spy than like a fantasy one, in other words.

The most noticeable difference between the strips and my (admittedly tenuous) memory of the books is that the strips carefully finesse Fleming’s vicious homophobia. Wint and Kidd from Diamonds Are Forever are here just good friends; Pussy Galore falls for Bond because that’s what girls do, not because he forcibly shows her the error of her lesbian ways. On the one hand, dropping the prejudice makes the strips much more palatable for a contemporary audience. On the other hand — homophobia was kind of what Fleming had to offer. When you remove the compulsive anxiety about manliness, there’s not a whole lot here. Except the art, of course.