strange creatures in a stranger land

Jason was born in Molde in 1965. In 2007 he moved to Montpellier. My mother was born in 1965 along with lots of other people. At intervals between then and now he has written and drawn comic books. He is the best living genre fiction writer in the world. Or someone else is. He writes. He draws. He might drink tea or coffee or perhaps he doesn’t drink either. He might dress as a werewolf and moonlight as a burglar, or simply sit at a desk and write and draw his comic books. I am almost certain my mother is not a burglar, but what do I know? Lots of other people write and draw comic books and some of them are as good as the comic books that Jason writes and draws.

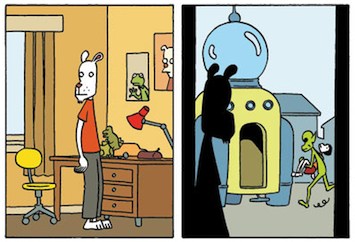

By now Jason’s signature is the stoic anthropomorphic dog, crow and rabbit blanks he uses in his books. Though the majority of his work features animal characters, Werewolves of Montpellier is set aside as his most “furry” book; furry being a shorthand for anthropomorphism as a device that carries meaning. Like other European animal drawers I have discussed under this masthead, Jason has no involvement with the subculture called Furry(tm) like I do, but Werewolves has some incidental thematic overlap with real life people who dress up as wolves for fun (and/or profit?).

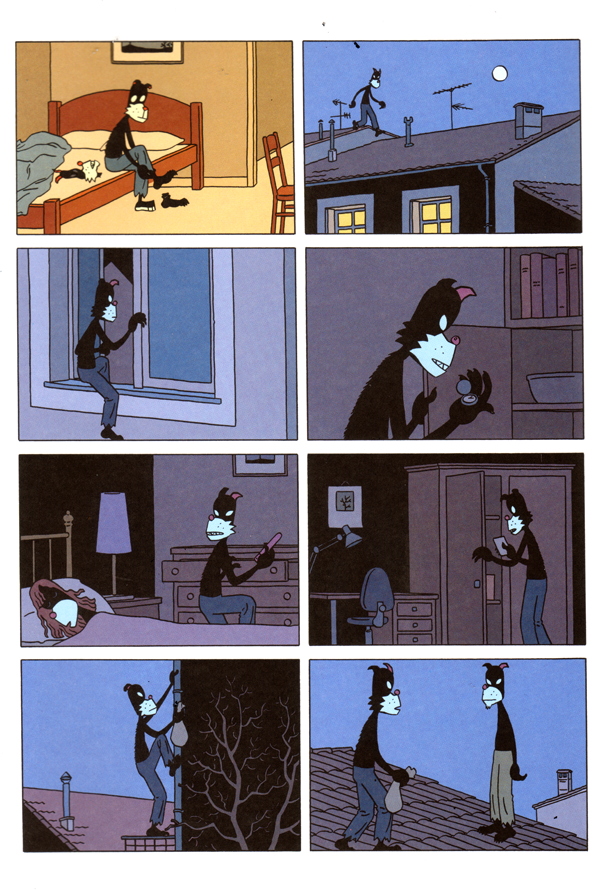

Sven is a Swedish artist and immigrant to Montpellier, France. He used to fill sketchbooks with drawings of Greta. Sven might have followed her to France, but she does not appear in the book. So by the time we meet him, Sven wanders aimlessly around the city drawing buildings. At night he is a cat burglar. Sven is a dog.

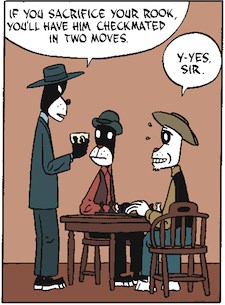

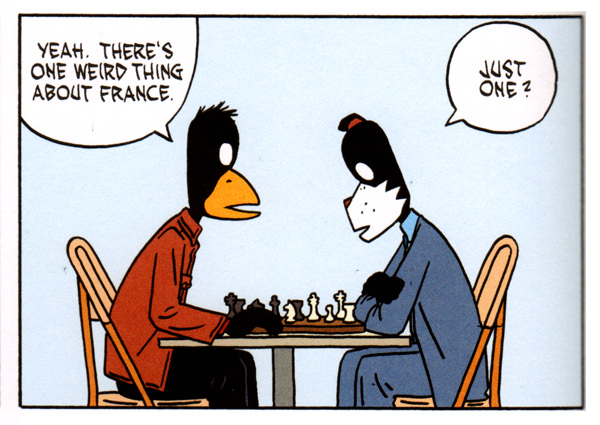

He speaks French well, though there is often more than a language barrier between Sven and his neighbors. He doodles the rooftops of Montpellier and plays chess with his Romanian friend Igor. When he prowls those same rooftops under the shade of night, he wears a werewolf mask. He outs himself at a party when he describes his profession as “jewel thief.” Sven “can hide in plain sight under a small talk double-backflip, but when the moon is full and Sven trades the ironical social mask for the werewolf, he enters a more primal state. As the werewolf, Sven abandons pretense and get to know his neighbors in a more intimate setting, prowling through bedside table drawers to uncover not just watches and pendants but lockets, loose Polaroid photos, a vibrator… all because of a story he tells about losing his faith in humanity after he’s taken advantage of for a little bit of money. After he’s finished he goes home to tell his neighbor Audrey across the hall all about it. She knows that he is in love with her, though he can’t really say it. His secret which bonds him closer to her than anyone else is the goal of his moonlit raids, not the loot.

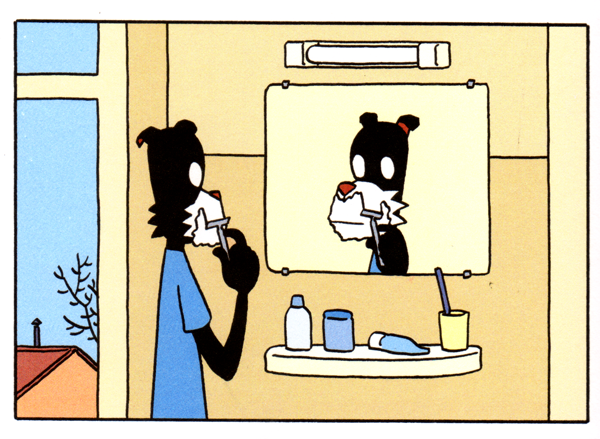

This is the tidy little meta-narrative of Werewolves: Sven, the immigrant artist, gets to put on an animal mask and go on adventures just like Jason, immigrant artist, drapes blank animal faces over his characters so he, and his readers alongside him, can fully immerse into the stories. We can see ourselves underneath the dogs and rabbits, and we don’t need the glasses from “They Live.” We see the work as self-aware of its own cartooning, the falseness of the animal faces in little moments, a dog emitting sweat-drops of nervousness, or a muzzle still white and furry after a shave. Jason’s animal faces are famously immobile like a mask.

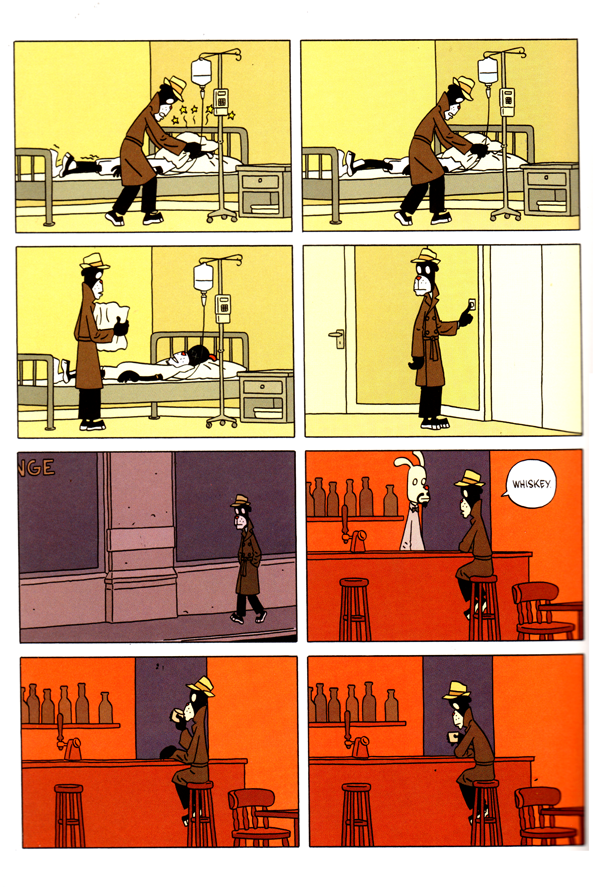

Jason’s work is often thought of taciturn and unemotional, but in Werewolves, the artificial blankness of the cartooning shores up powerful emotional moments. Sven runs afoul of a secret society of real Montpellier werewolves when a chance photo of one of his botched burglaries makes the front page of the local paper. After a rooftop tussle, one of the real wolves falls and breaks his back. His transformation is witnessed by hospital staff, and to put them off further question, his comrade has to kill him. After a frank exchange, an “I’m sorry” and an “I know,” the second werewolf smothers his friend with a pillow. The wolf’s final, agonized breaths are rendered with a trio of cartoon stars, as if he were bludgeoned with an ACME anvil. Afterward his eyes are a pair of cartoon Xs. Ordinarily used for comedy in classic cartoons, these old warhorses of shorthand highlight the unreality of what it must feel like to have to do this to a friend, and to underscore just how much the second werewolf doesn’t want this to be happening.

“Let’s see how you like it,” the second werewolf says after biting Sven in the book’s climactic scene. The primal werewolf state for him had been truly bitter; an isolation so profound he had to murder a friend to preserve it. Sven had pretended to be a werewolf to escape the loneliness of transplant life in Montpelier, to have a story worth getting close enough to someone to share it with. For the friendless werewolf, the lycanthropic transformation is a fate worse than death. For Sven, it’s a release from a life of putting on masks.

The joke throughout the book is that when you’re a dog, being a werewolf isn’t all that different. After a hilarious transformation sequence, Sven has a scruffier cheeks and a round nose instead of a pointed one. His eyes take a slight oval shape. Audrey is still the only sharer of his secret, only now he doesn’t have to climb through strangers’ windows. He can, no, he must stay at home. “She’s all yours,” Audrey’s ex girlfriend snarls at Sven before she speeds away, though hers and Sven’s relationship changes little after this. Once Audrey Gertrude is now free to literally “let her hair down” and drop her glamorous Hepburn imitation, her status as Sven’s object of desire melts away, and they are at the end what they always were; friends. Transformation is a means of escaping loneliness, even if it metamorphoses from a means to the end itself.

The aspect that makes this book furrier than Jason’s other animal stories is the space that Sven inhabits between being another blank dog character and as a stand-in for the artist. Furry is not a fandom in that it is not organized around appreciation between any specific commercial property or artistic movement. It is a creative subculture, where animal characters (either in stories or as autobiographical analogs) as well as the costumes we make for ourselves and each other to parade around in are facets or extensions of a creator’s identity. There is a performative aspect to Sven’s midnight lycanthropic haunts. Sven might be Jason’s werewolf mask. Or he could be fucking with us, a boring old cartoonist in the end.