This post was supposed to be about Brian K. Vaughn and Niko Henrichon’s Pride of Baghdad, the fictional graphic novel based on the true story of the pride of lions that escaped from the Baghdad Zoo after the initial bombing campaign in Iraq in 2003. Although that work has become freakishly and horrifyingly topical again, given the recent decision by the Obama administration to wage such a campaign against ISIS, my mind is elsewhere this week.

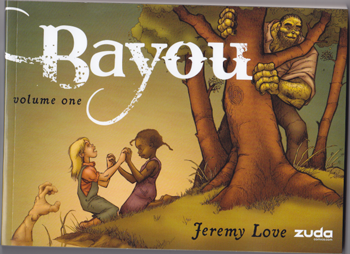

Last week, my students finished Jeremy Love’s brilliant Bayou Volume I, the story of African-American Lee Wagstaff and white Lily Westmoreland, two young friends negotiating the racial politics of 1933 Mississippi. The class was oddly silent for much of the second day, and when one of my (few) African-American students brought up a recent news item in our region, I knew I would be ashamed of myself if I didn’t discuss it.

Our class takes place on the idyllic Wittenberg University campus in Springfield, Ohio. Just a little ways down the road, in Beavercreek, John Crawford III was shot to death by the police inside of a Wal-Mart. He was holding a toy pellet gun. Another customer had apparently called the police, claiming that a man was waving a gun around in the store in a threatening manner. After weeks of refusing to release the video for fear of tainting the grand jury, Attorney General Mike DeWine allowed the security footage to be released tonight, only hours after the grand jury declined to indict the officers. The video is horrific. Appalling. “Cold-blooded murder” is the most obvious phrase that pops to mind.

Of course, it was also precisely what I expected.

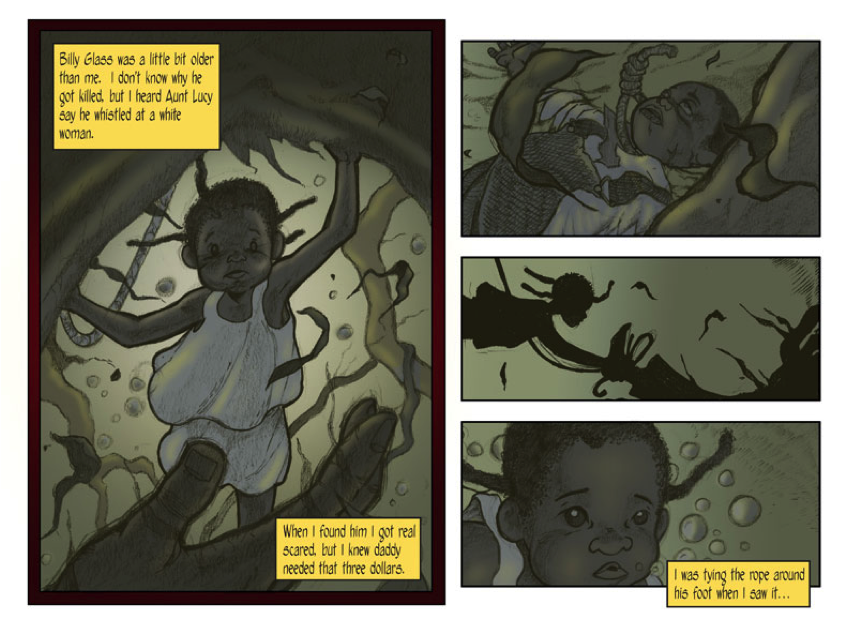

Last week, we didn’t have the grand jury decision, nor did we have the video. What we did have was one volume of a bizarre little comic that riffs off of Alice in Wonderland. By way of summary, the work opens with Lee by the bayou, preparing to jump in to tie a rope so as to haul up the lynched body of Billy Glass (a character meant to stand in for Emmett Till). Glass had been lynched for supposedly whistling at a white woman, his body left in the water.

While she is in the bayou, Lee sees a vision of Billy’s soul, and as we turn the pages, we realize that what we have seen is her memory of the incident, which she is recounting to Lily.

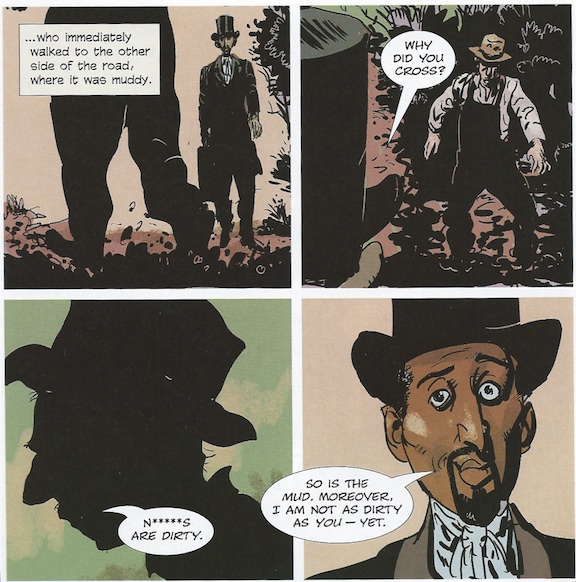

Lily expresses curiosity about the appearance of the dead body (as opposed to Lee’s genuine fear) and even goes so far as to parrot her mother’s racist diatribe about Billy “deserving what he got.” Qiana Whitted’s close reading of this scene is exquisite, telling us that

What we hear, then, in Love’s visual rendering of Lily’s whistle interests me greatly, for those tiny eighth notes generate a tremendous sound. We hear echoes of anti-miscegenation panic, a fear that reverberates unease even as the conversation hastily resumes. We hear the sense of white privilege that attends Lily’s ability to whistle freely, carelessly one could argue, in spite of her naïveté as a child repeating her mother’s words. But I believe that what Love also wants us to hear in this sequence is the “wolf whistle” of a murdered black child, along with the memory of just how much that sound costs. Perhaps what resonates most deeply in the white girl’s whistle are the sounds that Billy (and Emmett) are no longer able to make, were never free to make at all.

Furthermore, the iconic rendering of their faces invites identification, but that identification remains ambivalent. They are both iconic, so neither is closed off. While the racism Lily spews certainly inclines the reader to retract any sympathetic engagement, she is also a child copying her mother’s words. We should all know better, but, the implication is that sometimes we don’t.

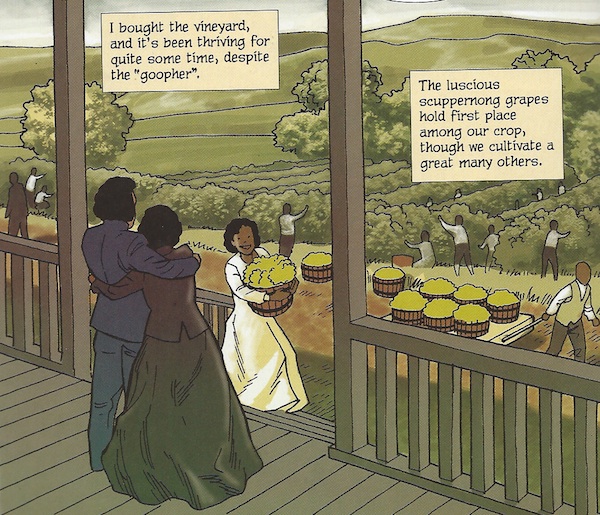

Later, Lily loses her locket in the bayou, and blames the loss on Lee, prompting Mrs. Westmoreland to demand Lee work to pay back the value of the locket, a demand to which Calvin, Lee’s father, promptly accedes because he doesn’t want to see his child “hurt over some white girl’s locket.”

While Lily would seem to be a bumbling villain at this point, she tries to go down to the bayou to find the locket and fix her relationship with Lee. She is eaten whole/kidnapped by a Cotton-Eyed Joe, a giant white man, while Lee watches, shaking in fear. As Lee runs away from the bayou in terror, a vision of lynched black bodies in the trees materializes, and she frantically runs through their feet.

Lee’s father is accused of the crime, although there is no evidence, and in a scuffle with the deputies, she is summarily knocked out by a white adult.

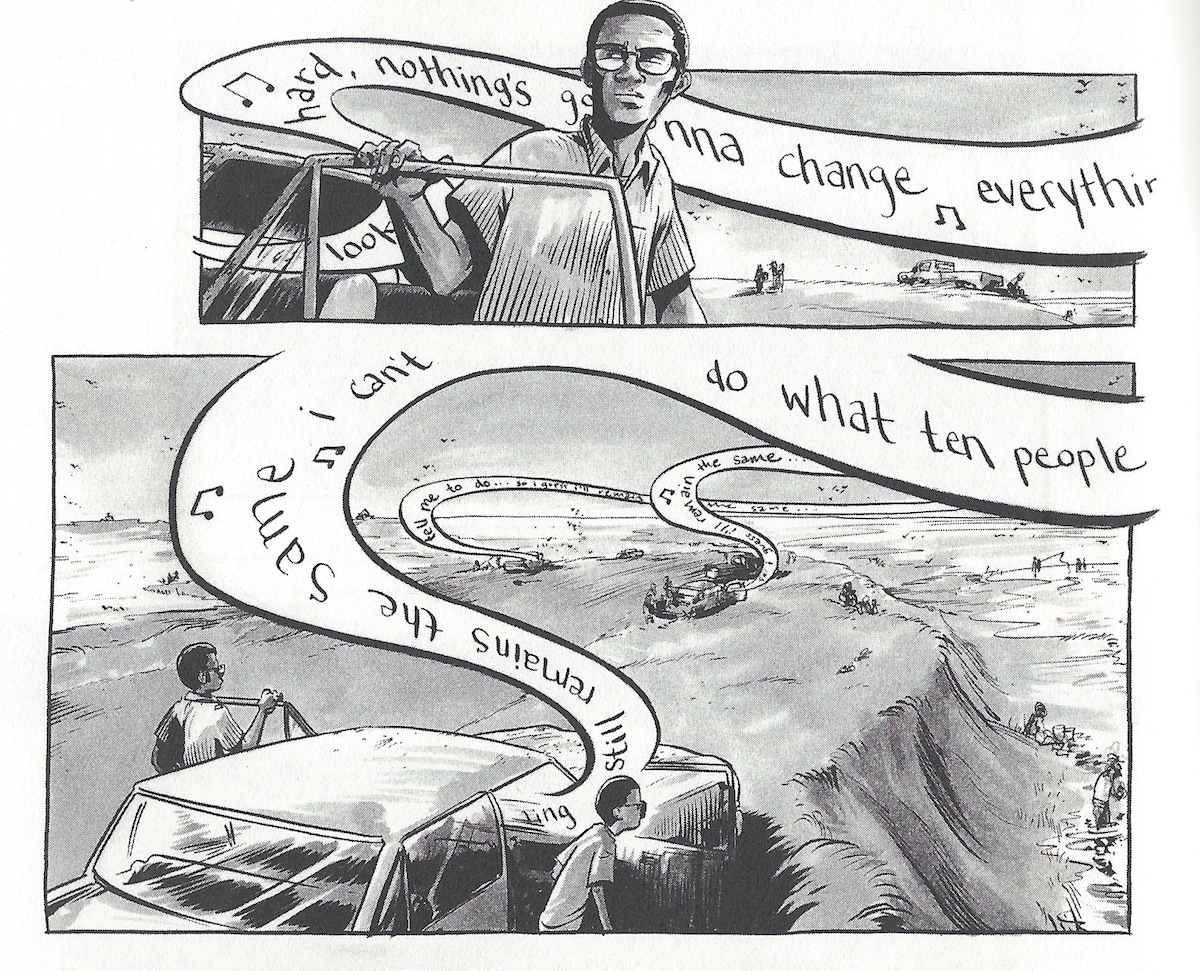

She journeys to the prison to see her father, who has been beaten mercilessly, where he tells her that her aunt will take care of her now, assuming that he will be lynched shortly. She decides to enter the bayou to find Lily and clear her father’s name. In this “through-the-looking-glass” moment, she enters a world in which racist caricatures are both personified and aggressive, and her only help is found in Bayou, a slave grown monstrous in his bondage, although he remains kind and fearful of the master.

She falls into one of Cotton-Eyed Joe’s traps immediately after reaching the land on the other side of the bayou, and while Bayou the character stitches her up, the spirit of Billy Glass tells her that she has very little time.

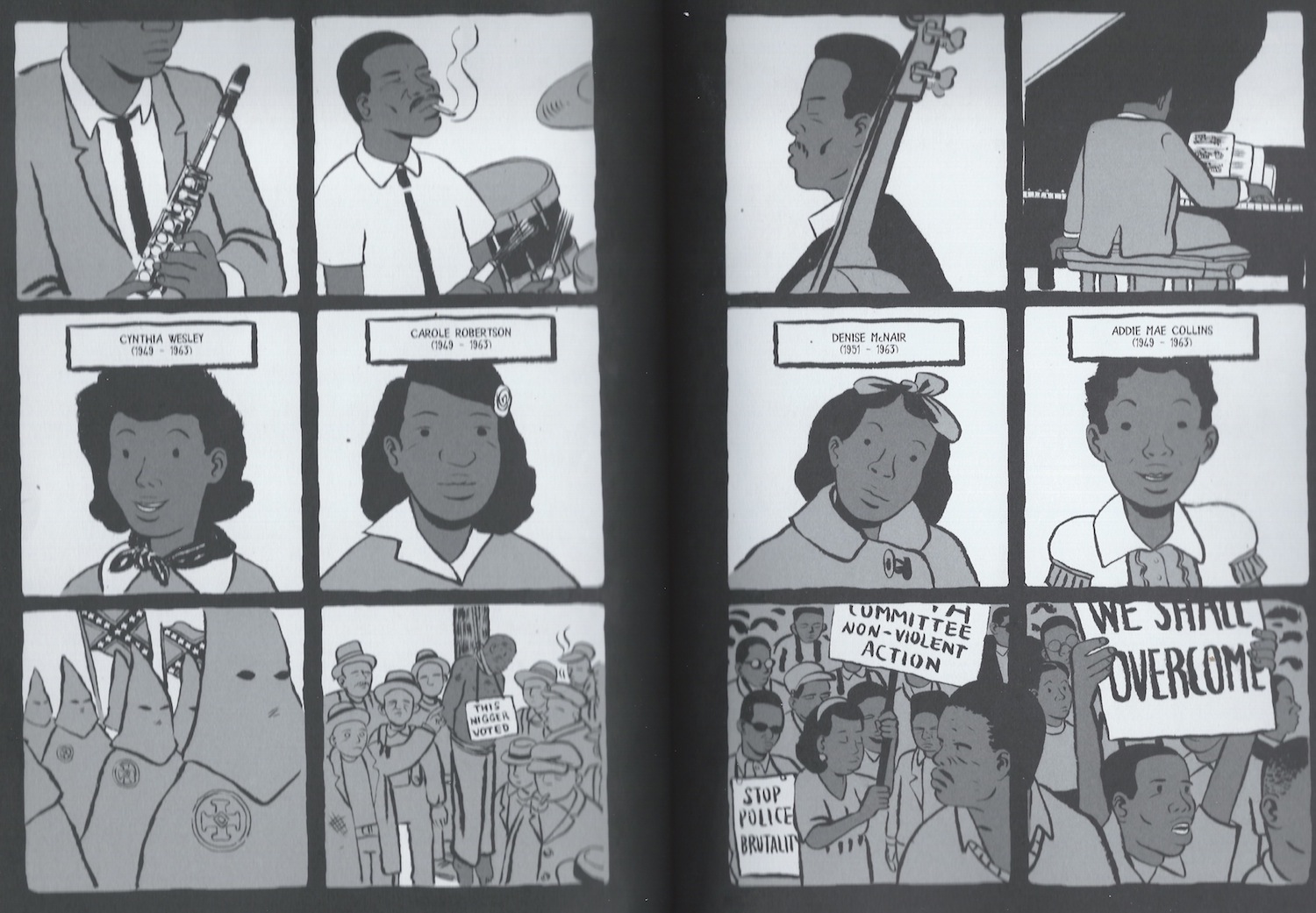

When I approach Bayou, the complexity of Love’s rendering of the racial landscape echoes not only America’s complicated and genocidal past, but also a present in which blacks are put in the unconscionable position of apologizing for history even while demanding justice. When we step through the bayou/looking-glass, we are stepping into America’s hysterical relationship to race, in which we must frequently repeat that it doesn’t matter now even when we encounter the most obvious evidence that it does.

Part of Bayou’s charm is feisty, spunky Lee, who insists that Bayou the character be courageous about his own life. We root for her, even though she is effectively a dead girl walking by the end of volume one. On the other hand, Love makes it clear again and again that Lee does not understand the limitations placed on her in the social structure, and she is hurt because of it. She is our heroine, but she is also before her time. While she may prevail in her quest to exonerate her father and to free Lily, we’ve already been told she won’t survive. Furthermore, we’ve seen her undergo obscene abuse at the hands of white adults, and her dreams or hallucinations indicate to a close reader that she is already—at minimum—a victim of psychological trauma as well.

As we discussed the circumstances of the work, my students tended to stress the historical context. “What it was like back then” was a phrase used frequently during the week we spent on the volume. Still, I stretched. “Why would Love write this in the 2000s?” “It was published in 2009. What was happening during this period that might make this relevant?” There were only 20 minutes left in class when someone bit. She brought up Ferguson, and referenced Beavercreek as well. The room was suddenly evacuated of sound, except for my “very good,” turning to scratch out another tick in the “Contemporary Contexts” on the board. I turned back to the classroom, and I could feel the white students receding. Not all, but many. There was shifting. There was uncomfortable fidgeting. And worst of all, eyes glazed.

They didn’t want this to be another lesson in how whitey was bad, but it was exactly the kinds of reactions I was seeing that I was hoping to critique. I drew attention to my own whiteness by way of tacitly acknowledging the discomfort. I asked—rhetorically—what it meant to have such conversations about race in the contemporary age.

Students of color and a few white students were energized, and we gabbed on about how Bayou could enrich our reactions to these current discussions for 10 minutes. The remainder of the class was lively, but I couldn’t shake the feeling of that moment of out-of-hand rejection of a text that was trying to teach us more productive ways to respond to discussions of race in contemporary America, and by the end of class, I felt deflated.

Perhaps I was more deflated more than usual after a rough class, because I’m currently working on a presentation for MLA on the science of memory, recent neuroscientific findings, and Bayou. I was invested in the text, and contexts, in ways I could only gloss in class. Tentatively entitled “My Children Will Remember All of the Things I Tried to Forget,” I ask us to imagine a mouse alone in a cage whose feet are exposed to electric shocks. Alongside of the shocks, the scent of cherry blossoms is piped into the cage. This is repeated until the mouse demonstrates an aversion to the aroma, and then the mouse has children. The pinkies are isolated from the parents and are never exposed to similar conditions, but nonetheless show a similar antipathy; the scent of cherry blossoms inspires only terror. I recount a study published recently in Nature Neuroscience, in which researchers found that mice do indeed transmit aversion between generations without actual social contact. Somehow, traumatic experience is genetically encoded, etched into the make-up of these animals. I ask if it is not too far of a stretch to believe that, perhaps, humans function in the same way.

Such a finding has fascinating repercussions for the study of intergenerational trauma, long the province of literature scholars, dwelling on the outskirts of “proper” psychological and neuroscientific literature. The finding suggest in part that slavery is not over, and that the subsequent abuses have been writ small on our genetic codes. There are ample studies (some ongoing) demonstrating lingering prejudice in even the most devoted progressives, yet popular thought still turns away.

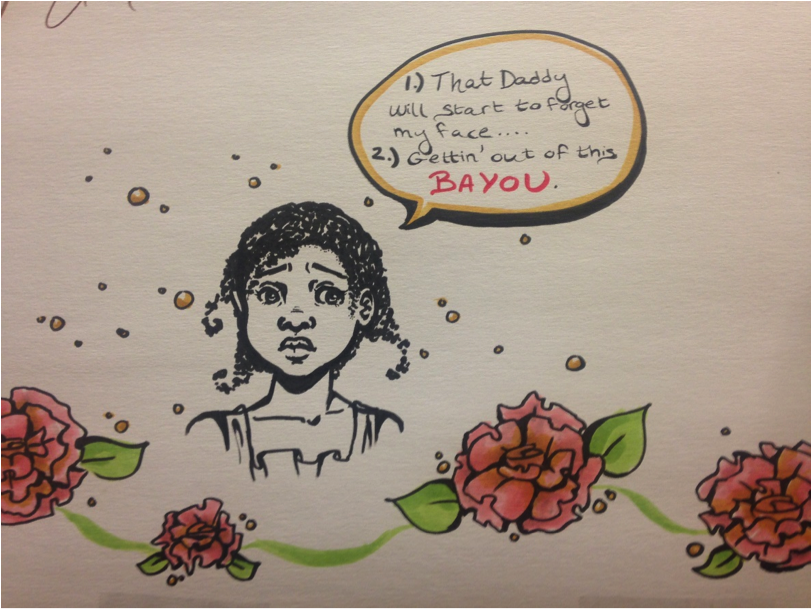

I spent the weekend trying to shake off the lingering feeling of profound failure, as well as worrying about the grand jury convening on Monday in Xenia, just up the road from my home. What had I said? What had I failed to say? On Monday, I drove into campus a bit before 6am, hoping to plan myself into a less agitated state. And I arrived to find the illustration below on a poster I made at the beginning of the semester, with a cartoon of myself asking “What are you most worried about? What are you most excited about?”

Clearly, someone was listening. Or at least, they were hearing between the lines.