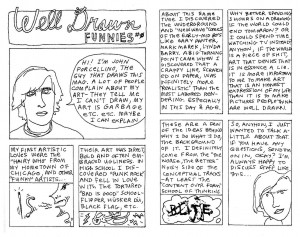

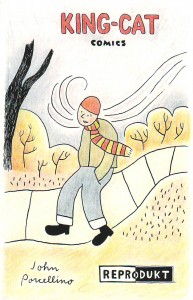

Before I read The Hospital Suite, I was only vaguely aware of John Porcellino as a sort of folk hero. He packed up and left Chicago near the turn of the century (around the time I moved here myself), and some 15 years on still seems to be the patron saint of comics in this city, or maybe the Midwest in general. Cartoonist laureate of a Carl Sandburg poem. Any place where folks work hard and make the best of it.

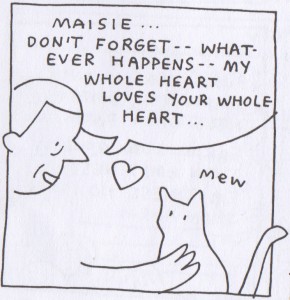

Paul Bunyan had an ox. John Porcellino, a cat. Her name was Maisie. She’s been memorialized in no less than three Sufjan Stevens songs—more if you count the b-sides. I recently learned that a cabal of suburban mail carriers named her a minor deity. They want to get her on a stamp. They say that on clear winter days, at first light, you can feel the spirit of the cat making copies of out-of-print comics at the Wicker Park Kinko’s. I met some guy at Quimby’s who claims he communed with her there. Three beers in he admitted she had to correct his pronunciation of Kukoc.

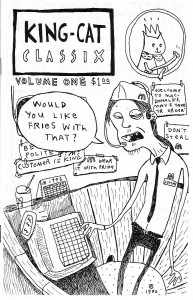

I don’t know, I guess you read comics. You probably know the lore. But all I really knew up until I read The Hospital Suite was that Porcellino has a pure punk heart and a 90s-era webstore, and I confess that my more cynical side wondered if that wasn’t, on some level, super fucking ridiculous. I’d like to be the kind of person who buys mail-order zines, but the truth of my life is that I read celebrity gossip magazines and persist in ordering almost everything from Amazon even though I know it’s evil. I truly wish I cared.

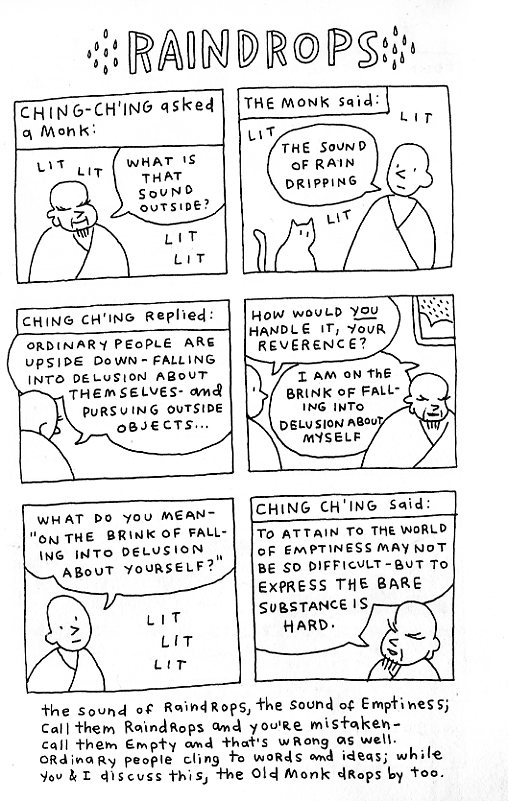

In any case, I’m grateful to the good people at Drawn & Quarterly for publishing this work in a format that feels accessible to jerks like me. While I could see Porcellino’s appeal from page one, there were moments early on when I worried The Hospital Suite was another “good patient” story. I also found the current of what I’d reluctantly call spiritual comics to be a bit much—not a deal breaker, but always off-putting. (I love Ron Regé Jr, but there is no plane to which I could ascend where I would be inured to the hilarity of his wizard robe.) Slowly, though, it dawned on me that I was reading something rare and real and special, and not at all ridiculous, and by the end of The Hospital Suite I felt for Porcellino a sort of affection that is a rare sensation in reading comics, or really all of literature, or maybe life. I’d compare it to how I feel about David Foster Wallace or Lynda Barry. I mean to say he shines a light.

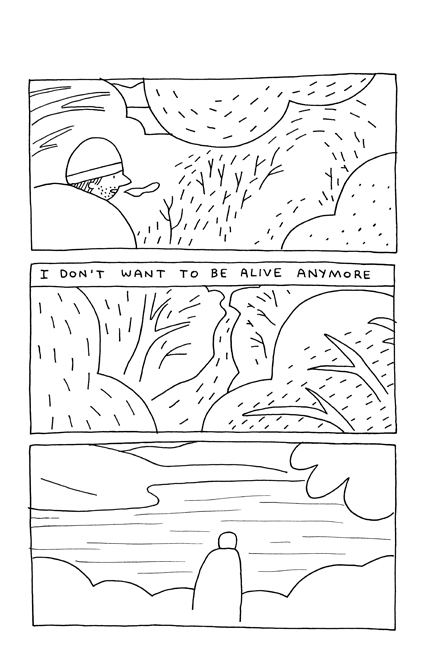

Autobio is a crowded category, not just in its number of practitioners but also in its sensibility. It’s often a jaundiced genre—frenetic, claustrophobic, uncomfortable. Neurotic. Obsessive. Tortured. Overwrought. Within The Hospital Suite, there are traces of all the classic themes: ambivalence toward the responsibilities of adulthood, depression, masturbation, being broke. The chief difference is, despite a grueling fight for his life and nigh on a decade’s worth of catastrophic diarrhea, John Porcellino somehow seems to be the least miserable bastard in comics. Of course—and this is critical—he’s not quite happy, either. He’s something else. And whatever you want to call it, it’s a breath of fresh air.

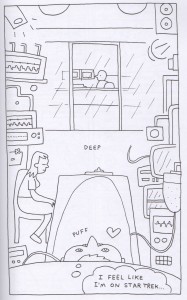

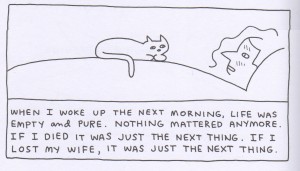

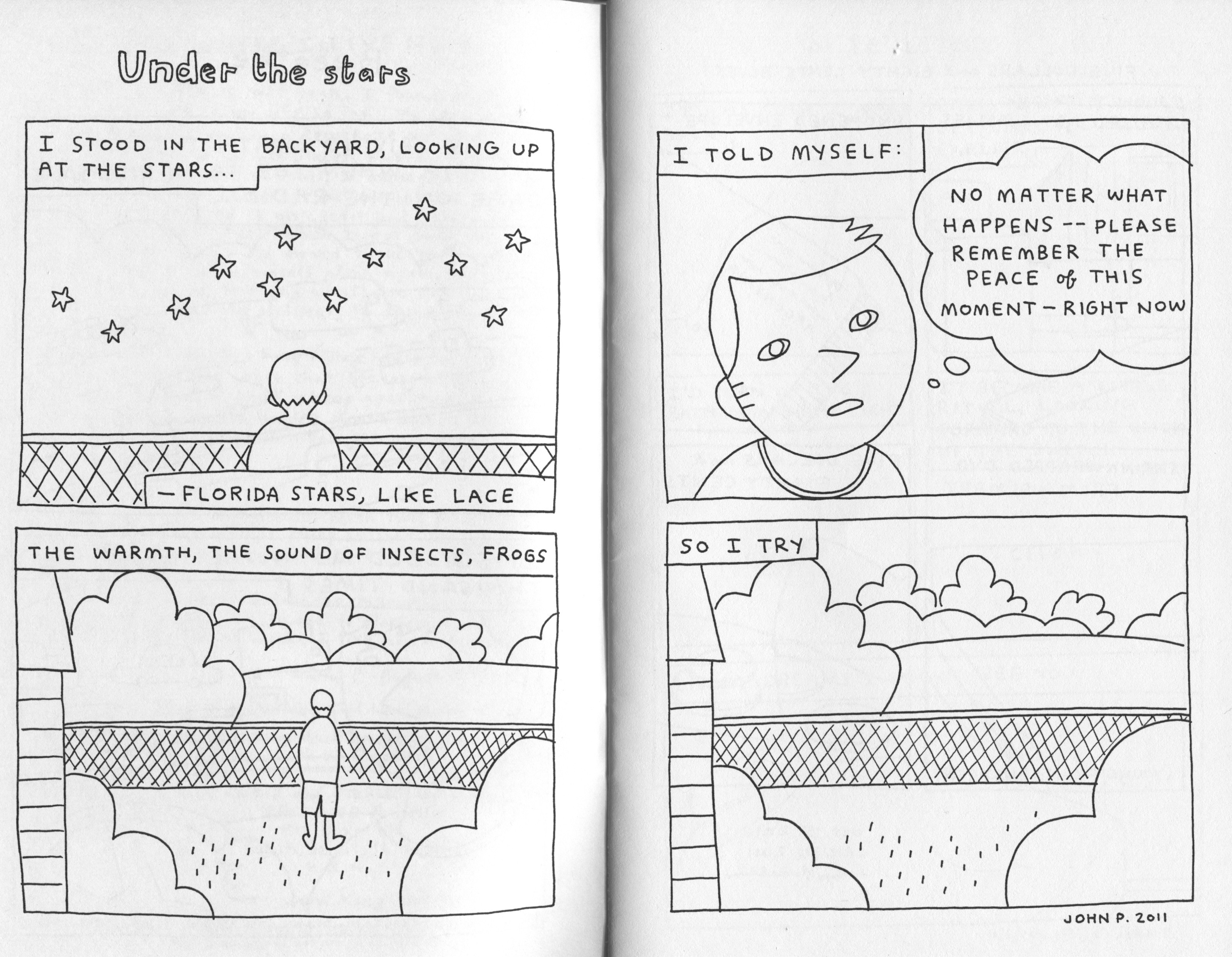

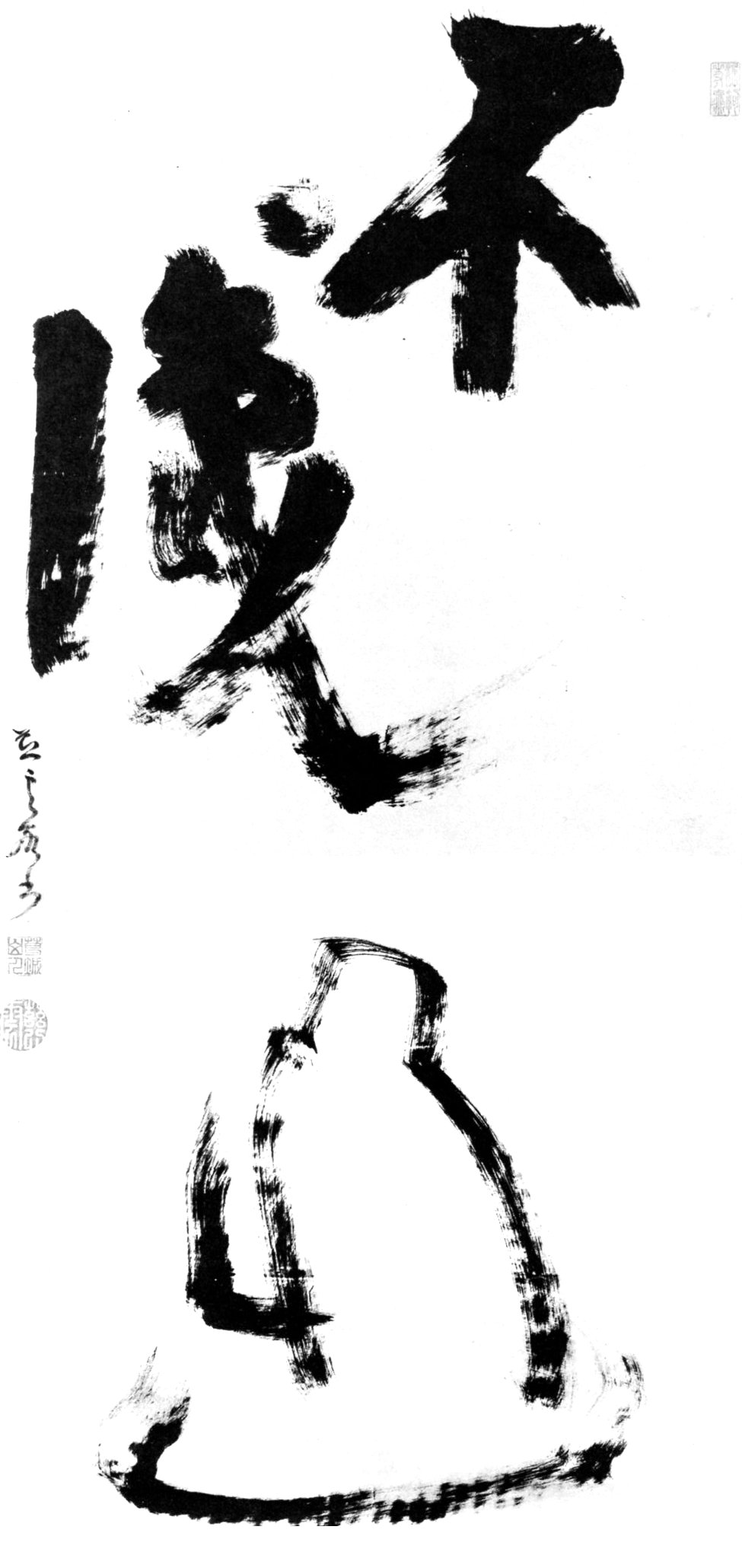

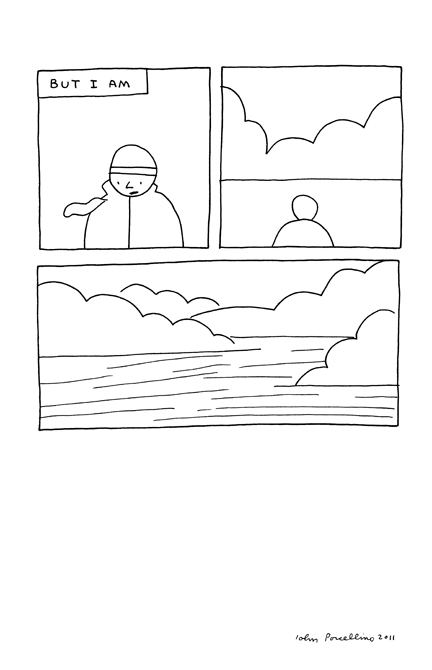

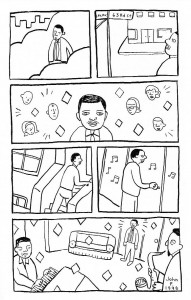

There is a palpable sense of calm conveyed by Porcellino’s simple aesthetic. I gather that’s just how he draws, but it suits the subject matter here very well, offsetting the intense distress he depicts throughout The Hospital Suite. I’ve heard him say that his drawing is sometimes referred to as bad. I find that astonishing, but it certainly sounds like something my dad would say. Of course anyone who has aspired to minimalism in any area of life, artistic or otherwise, will recognize the sophistication required to draw stripped-down pictures like these. It’s advanced iconography—a very high level of graphic design—and that Porcellino manages to pack so much charm into drawings this spare is remarkable, if not unheard of (cf. Allie Brosh). Occasionally he flashes his chops in a cool composition, like this scene from his sickbed that captures the whole Starship Enterprise vibe of being in the hospital.

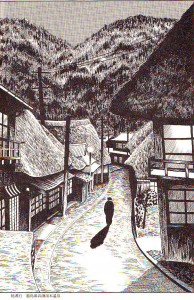

But I think Porcellino is at his best when he keeps things simple. He has developed an idiosyncratic shorthand to convey outsized feelings—the good, the bad, and even the ineffable. Probably my favorite thing about the book is the little hearts he draws to convey all the love he feels in the universe. He seems to tap into it almost everywhere, including the post office.

Reader, I don’t know about you, but this does not even remotely resemble any interaction I’ve ever had with USPS.

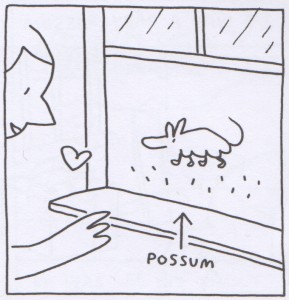

Or possums? ~~oO{:> ……..(/*o*/)

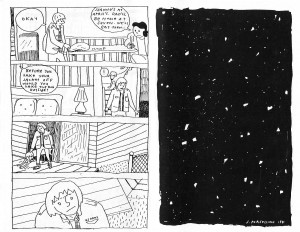

Structurally, The Hospital Suite isn’t quite sound. On one hand, Porcellino does an excellent job of distilling a narrative from an incredibly complex system of mental and physical illnesses that span a long period of time. On the other, we have the book’s clumsy division into three distinct, but overlapping, sections, plus several wholly unnecessary appendices. The central paradox of Porcellino is that his stories are very processed—aggressively reduced and refined—but feel entirely organic. Untouched. In sharp contrast, the section breaks feel artificial and distracting, and it messes with the magic just a little. One of the advantages of comics as a medium is the ease with which they can accommodate more than one timeline. These stories should have been stitched together with more care.

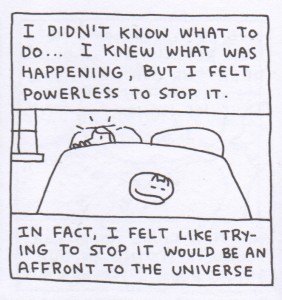

Overarching the structural concerns is the book’s lack of dramatic tension; the terror of the Mystery Illness is offset by the reader’s sure knowledge that Porcellino did in fact survive this experience. Even when emotions run high, the stakes feel low. Some stories are so engrossing that you feel “worried” even when you know the outcome, but The Hospital Suite never quite manages to transcend its own inevitability. I don’t know, it might be unfair to expect a Zen Buddhist to ratchet up the drama.

Admittedly, this is where we brush up against my limitations as a critic: the places in the text where I wondered if its “deficiencies” were areas in which there was real room for improvement, or just a different way of looking at the world. Often I admire Porcellino’s clear perspective. (Even when he’s talking about the shame spirals of obsessive-compulsive disorder, his gaze is cool and level.) But sometimes I get the sense that he simply hasn’t done the hard work of what Justin Green has described as presenting the self as a “specimen.” The world of The Hospital Suite is a place in which things happen to John Porcellino. There is no real sense that he assumes any agency in life.

Whether that lack of agency is a personal problem, a spiritual belief, or a syndrome borne of years coping with a debilitating, unpredictable illness is difficult to discern. (Maybe it’s all of those things.) I’ve read that the events in The Hospital Suite span two divorces and three relationships—something that wasn’t quite clear to me from reading the book. It’s understandable that Porcellino didn’t want to delve into the particulars; these are real women in the world, after all, and in some ways the dissolution of those relationships seems tangential to the story he’s trying to tell. But I found myself giving him the side eye, hard, in some of the sequences about his first wife.

I wonder if, as an autobiographer, the decision to do what was best for his cat instead of his relationship was something that Porcellino could have delved into more deeply.

But no one’s perfect, you know? And as much as I love autobiographical comics, they tend to celebrate imperfection in a way that’s slyly self-congratulatory. They relish rolling around in the shit. Whatever flaws are in The Hospital Suite, the author seems to come by them without ego or agenda. Which all sounds rather humorless, doesn’t it? He’s very funny, though.

I’m not a spiritual person, or the kind of girl who has easy access to all the love in the universe. Frankly, I’m more disdainful and suspicious of those things than I’d like. As much as I wish I were a special disgruntled snowflake, this perspective is, increasingly, a cultural norm. From the milieu of autobiographical comics to television’s recent obsession with antiheroes, drama isn’t really about Good People right now. It’s hard to make them seem compelling, or even believable. As a creator, it’s all too easy to explore the nuance of being a garbage person. It’s also easy, from a reader’s point of view, to sigh in relief that someone else in the world is just as bad (or, better, worse) than you are.

It’s more difficult and brave, I think, to make art that takes people outside themselves and shows them something larger. More than craft or even sheer likeability, it is that reach that makes John Porcellino’s comics remarkable. It’s a quality I can’t quite hope to convey in these 1,500 words. This is where I’d draw the heart.