Most of the comics I’ve consigned to the Manga Hall of Shame are there for obvious reasons: a script so hammy you could serve it for Easter dinner, for example, or a female character conjured straight from the pornographer’s imagination. But the manga that earns my greatest scorn isn’t a boob-fest like Eiken or Highschool of the Dead or The Qwaser of Stigmata. No, my least favorite manga looks positively wholesome in comparison, with a nifty cover design and a familiar corporate logo just below the title. Don’t be fooled, however: Gandhi: A Manga Biography is a bad comic.

As I noted in my original review, Gandhi has problems like a dog has fleas. The script is tin-eared, with passages of old-timey formality punctuated by California dudespeak. (One character actually calls another “bro.” No, really — “bro.”) The pacing, too, is uneven, focusing so heavily on Gandhi’s formative experiences in South Africa that his crusade for a sovereign India reads more like an epilogue than a second act. Equally frustrating is author Kazuki Ebine’s tendency to reduce major historical figures such as Jawaharal Nehru to walk-on roles; from the few panels in which Nehru appears, one might reasonably conclude that Nehru was just one more person that admired Gandhi, and not one of Gandhi’s most important proteges — or, for that matter, India’s first prime minister.

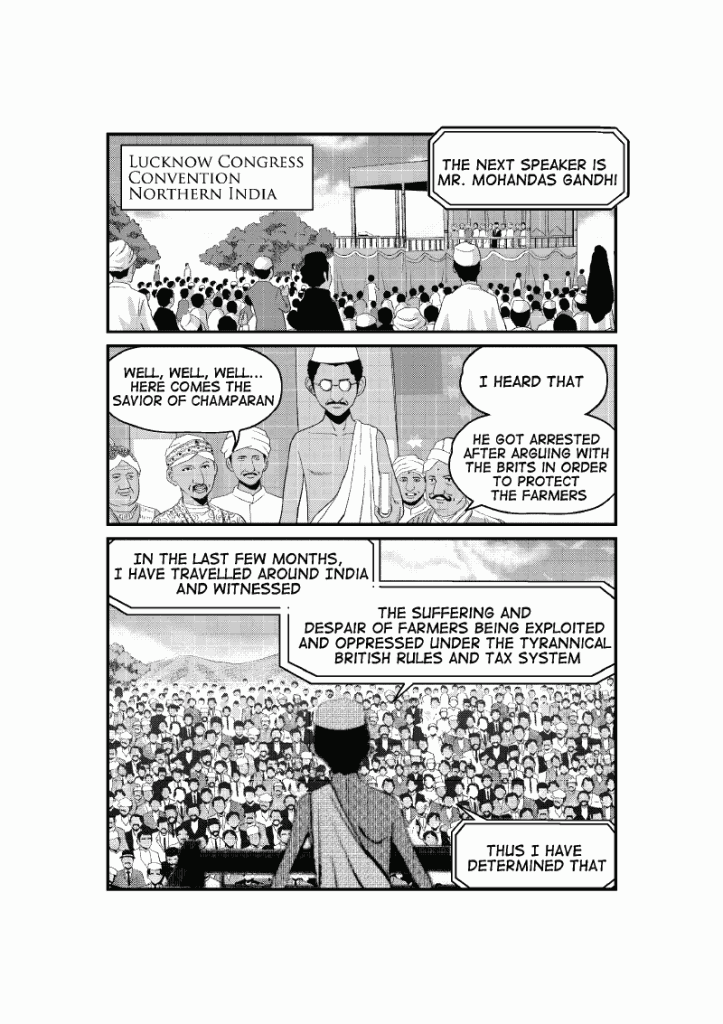

The comic’s greatest sin, however, is that it’s boring, transforming the life of a truly brave and complicated human being into a series of artlessly executed tableaux. The script, in particular, labors mightily under the weight of Gandhi’s prose, which is frequently juxtaposed with Ebine’s clumsy attempts to articulate the opposing point of view. Confrontations between Gandhi and Muslim activists, British authorities, and separatist skeptics are presented with all the sophistication of a third-grade school play, treating Gandhi’s adversaries as mustache-twirling villains and Gandhi as an unwavering paragon of virtue, always handy with a sage remark.

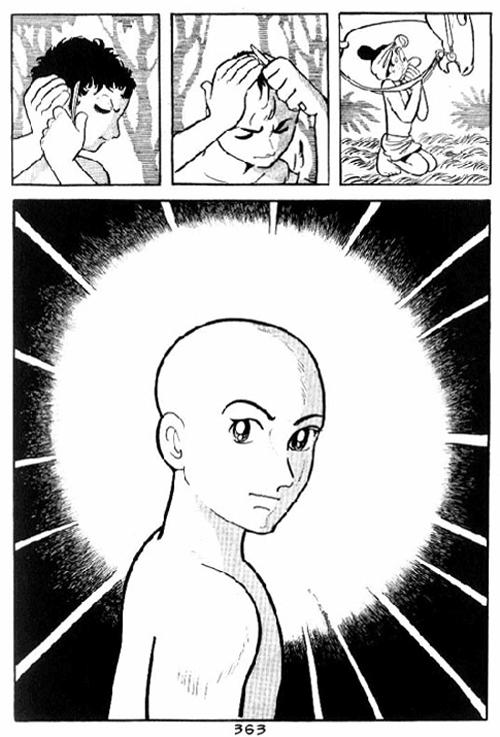

Ebine also struggles to tell Gandhi’s story with a meaningful sense of urgency or coherence; events are presented chronologically in brief, disconnected vignettes that rely excessively on talking heads to create continuity. Consider the following scene: in April 1919, Gandhi organized a national strike to protest the Rowlatt Act, an anti-terrorism measure that granted British authorities the power to imprison, without trial, enemies of the state. Ebine depicts a strike-day confrontation between protestors and soldiers in Amritsar, a village in the Punjab state. That massacre, however, is staged so poorly that it’s difficult to follow what happens. First we see tanks rolling through narrow streets; then we see children playing on the periphery of a demonstration; then the British soldiers begin firing on the crowd; and last, Gandhi stands over victims’ bodies, sadly shaking his head. The disjointed imagery poses more questions than it answers: what triggered the shooting? Where were the soldiers standing in relation to the crowd? How many people were present? What happened to the large number of tanks seen in the very first panel? And when did Gandhi arrive on the scene: moments after the carnage, or a day later? Neither the dialogue nor the illustrations address these basic issues, robbing the scene of its potential dramatic or explanatory value.

Then, too, Ebine does such a poor job of recreating the period and the setting that the reader never feels transported to South Africa or India. Ebine focuses most of his efforts on costumes, recreating hats and military uniforms in just enough detail to suggest the early twentieth century. His backgrounds, however, are so devoid of information that Gandhi could just as easily be taking place in modern-day Texas as in 1920s India. Simplification is a common practice in manga, but in skimping on such elements as buildings and streetscapes, Ebine misses an important opportunity to show us how Gandhi’s environment shaped his thinking, his personality, and his strategies for non-violent engagement with the British.

Contrast the sparseness of Gandhi with a historical work such as The Times of Botchan, and Ebine’s poverty of imagination becomes that much clearer. In The Times of Botchan, Jiro Taniguchi uses period detail to immerse the reader in novelist Natsume Soseki’s world: we see the uneasy mixture of Western fashion with traditional Japanese costume, and the gleaming modernity of trolleys and railway stations contrasted with centuries-old homes. Taniguchi’s drawings do more than tell the reader, “This story takes place during the Taisho period”; they help the reader understand how a writer living in that particular place and time might have produced a satirical novel such as Botchan. Ebine’s illustrations, however, are too perfunctory to convey the squalor in which India’s untouchables lived, or the segregated train cars to which Indians were consigned — details that would have demonstrated the specific social injustices that Indians faced both at home and in South Africa.

To judge from the generally favorable reviews of Gandhi, I have no doubt someone will be offended by my suggestion that Gandhi is a bad comic. But when the basic mechanics of the book are so poor, and its treatment of complex, ugly periods in colonial history so simplistic, it’s impossible to give Gandhi a pass just because the subject matter is high-minded.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.